Explore Masterpiece

Miss Scarlet | special feature

Miss Scarlet Season 7 Confirmed as the Series Finale

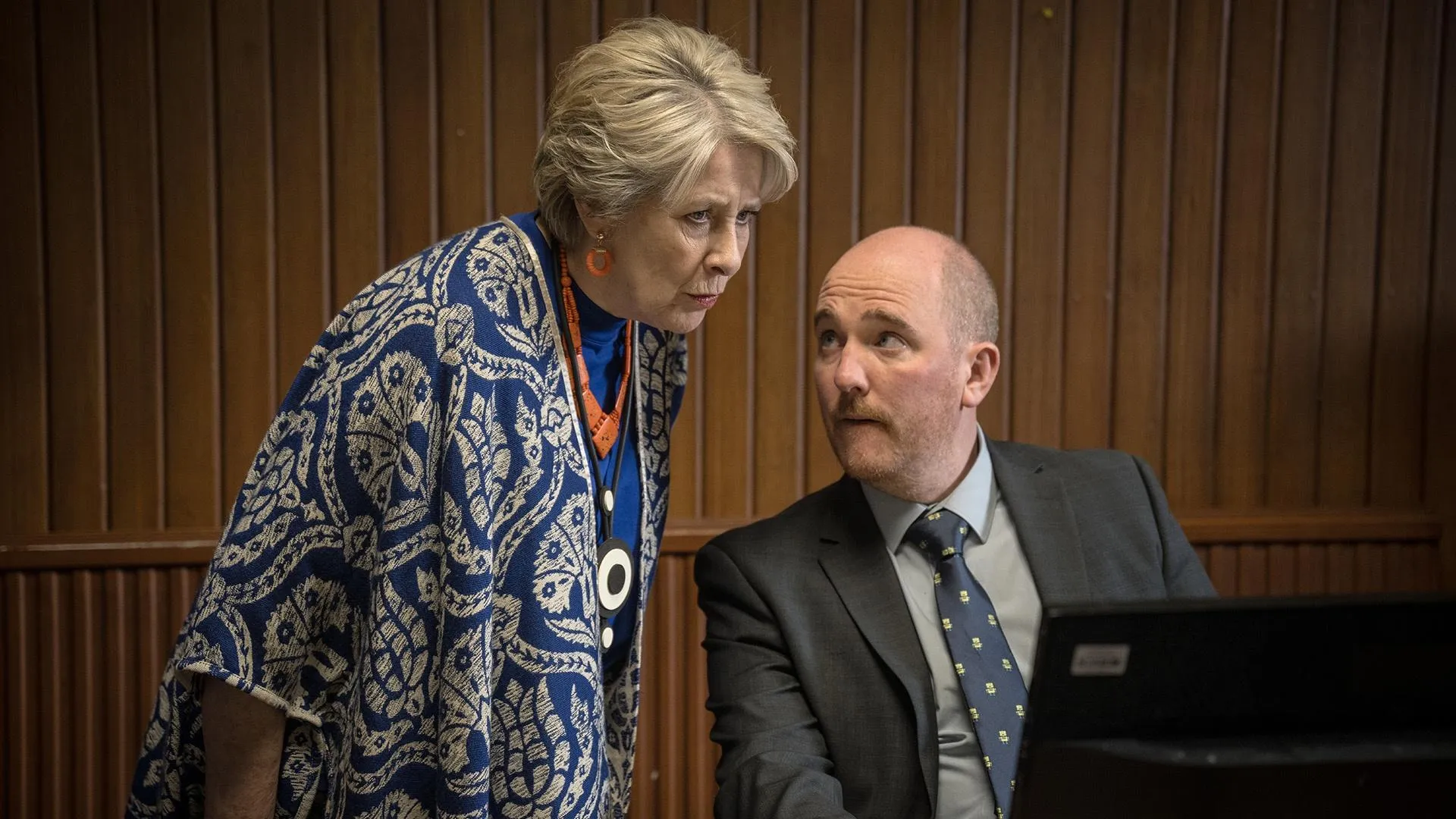

The Forsytes | preview

"This Is Our Moment" Preview

MASTERPIECE Newsletter

Sign up to get the latest news on your favorite dramas and mysteries, as well as exclusive content, video, sweepstakes and more.

Enter Your Email Address

Popular Shows

Support Provided ByLearn More