Len Zon

Len is a cancer researcher at Harvard Medical School and a practicing oncologist at Children’s Hospital in Boston.

Meet cancer researcher Len Zon in these videos from the NOVA's "The Secret Life of Scientists & Engineers." Len studies zebra fish to better understand the biology of cancer tumors. The gene set of the zebra fish is similar to humans. The fish are transparent, revealing internal organs. Len is also a musician, playing the trumpet and the shofar, a ram's horn.

“We have red fish. We have green fish. We have blue fish.”

Science:

Len Zon is a cancer researcher who uses zebrafish to learn how to treat cancer in humans.

Secret:

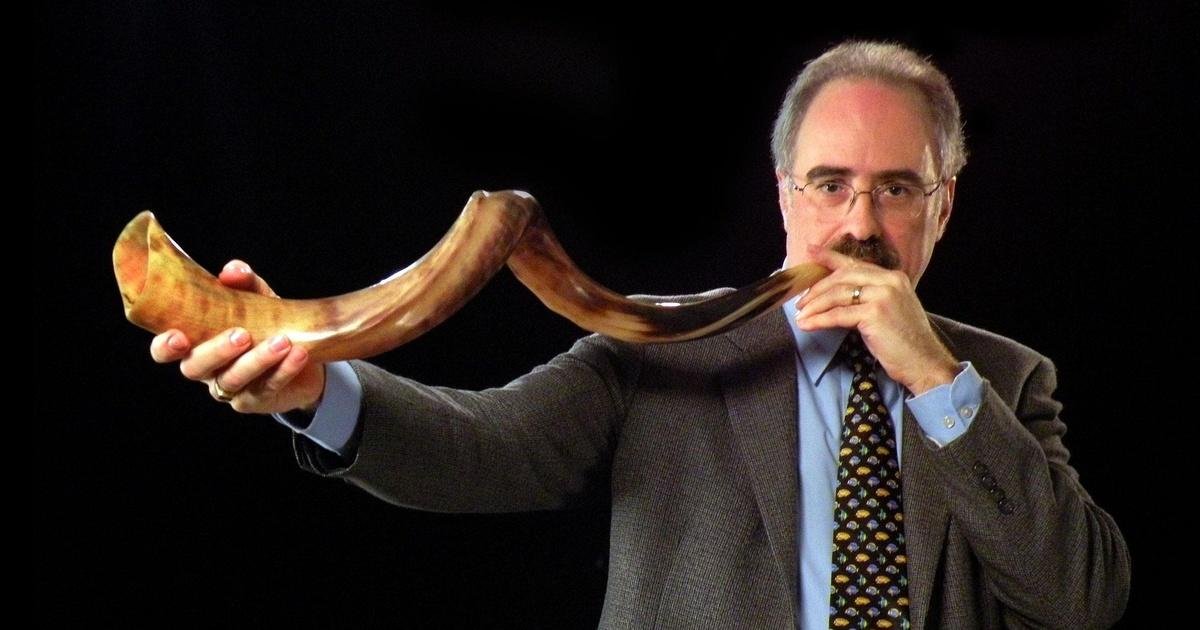

Len plays the shofar, a ram’s horn that is often used in synagogue on the Jewish high holidays.

Fishing for Science

Len Zon goes all Dr. Seuss and studies zebrafish to find treatments for cancer.

The Longest Note

Len Zon brings people happiness by blowing into a ram's horn.

30 Second Science with Len Zon

We give Len Zon 30 seconds to describe his science and he uses the phrase "completely transparent."

10 Questions for Len Zon

We ask Len Zon 10 questions and he tells us he's got 150,000 fish.

Shofar so good

Like most things that are worthwhile, playing the shofar takes a lot of patience and practice. In the Jewish faith, being a shofar sounder is an incredible honor.

It is your job as the Ba’al T’qiah (which awesomely translates to “Master of the Blast”) to usher in the high holidays, particularly Rosh Hashanah, when the sound literally announces the commencement of the new year. Even in our small studio, the shofar produced an incredibly powerful sound that must be even more all encompassing when blown in a house of worship. However, this full, beautiful sound that Dr. Zon produced doesn’t come easily, as evidenced by my rather, er, pitiful attempts to copy his trumpeting. Check out the video in the player above and see for yourself.

They go together

By: Len Zon

Medicine and music are linked. It’s partly due to the wiring of our brains: both fields are mathematical, relational, and conceptual. It also comes down to how we use our brains. Medicine, like music, is an art, a large knowledge base upon which we draw and build with each new patient we meet. Medicine depends on teamwork: treatments are developed and refined in consultation with colleagues, much like a theme is passed and adapted among instruments in an orchestra.

Because of these shared characteristics, it’s not surprising that you’ll find many doctors and scientists harboring musical talents. Come see a performance of the Longwood Symphony Orchestra in Boston—my musical outlet since 1984—to hear this firsthand. While there was a brief period of time when I considered becoming a professional musician, my heart was always in science and medicine, and it made more sense to me to make music my hobby.

I played trumpet all through high school—first seat in the orchestra and band in a pretty big school—but my trumpet-playing peak came during the last year of college. I had applied to medical school early decision and essentially was able to do what I wanted during my senior year of college, so I played music: three orchestras, two bands, a brass quintet, with a choir, at a church. I was playing about seven hours a day, and I got pretty good. It was a wonderful year. A lot of people asked me why I wasn’t going into music. That year, I interacted with many people who were going into music, and I was impressed by how talented everybody was, so I knew the competition would be immense to actually make it as a trumpet player (probably a hundred times harder than making it as a doctor). I felt like I had a good shot at medicine and should lead with my strengths. Besides, the moment I was born, my mother said, “You’re going to be a doctor.” Maybe it was a bit predestined.

It wasn’t until medical school that I realized the great opportunities in research; before then, I had seen my future in community medicine, pediatrics, my own practice, something like that. Now, I devote my time to stem cell research and find my musical outlet in the Longwood Symphony.

For musical doctors and scientists, the two worlds are never entirely separate. On a personal level, one of my favorite stories is when I was playing a Mass at a church and I had a solo with the organist. During a break in my solo, an usher asked me to assist someone who had fainted in Pew 53. The person had a pulse and began to recover a bit, so while someone called for EMTs, I was able to go back and come into the song at just the right time. On a larger scale, the mission of the Longwood Symphony Orchestra involves supporting health-related non-profits. And other medical community-based musical groups across the country have similar goals.

I think that in some ways, the genetics are hardwired. A lot of us have a love of the arts and music, and it’s just fantastic having the opportunity to nourish our sense of creativity both inside and outside of the lab.

Getting the job done

When our two daughters were born, my wife and I went through just about every emotion you can imagine. (Of course, my wife also went through just about every physical sensation you can imagine—thank you, Ann!) The birth of a child is an amazing time—something you never, ever forget.

When Len Zon’s son was born, though, there was an added element of excitement that’s only likely to happen when one of the parents is a scientist. It was 1993 and Len had just learned how a baby’s umbilical cord blood could be harvested, saved, and potentially later used in the treatment of a wide array of genetic diseases. I’ll let Len take it from here….

“I attended one of the first cord blood transplantation seminars. And I was amazed that this actually was working for kids who had genetic diseases. And so at that point, I decided it would be great to harvest my own son’s cord blood. At that time, the head of the blood bank at Children’s Hospital was also interested in storing cord blood, so I organized with him that he could collect my son’s cord blood. And when we were going to the hospitals for visits, we were sure we had told the obstetrician that we were going to do this entire procedure.

“What we didn’t expect was that my wife would go into labor about a month early. And while she was in labor, at the very last moment, before she was about to deliver, I realized that I wasn’t storing the cord blood because we were so involved in the moment. So at that time, I called one of my friends, Jed Goreland, who was the head of the blood bank. And I said, ‘Linda’s about to go into labor and we really need you to come and harvest the cord blood samples.’ And Jed said, ‘Len, I’m teaching at the medical school right now, and I really can’t come. You have to do it yourself.’ And I said, ‘But I don’t want to do it myself!’ And he said, ‘You have to do it.’ And so he told me the procedure, which is to wipe off the cord and to milk the cord as much as you possibly can into a flask with anti-coagulant in it. And he said he’d come by later after he taught and he’d collect the flask.

“I had multiple thoughts. One was, ‘Maybe I should just bag the entire idea’—at the time, cord blood transplantation had only been done a few times. And so maybe it wasn’t worth getting this blood stored. On the other hand, as a scientist I hate to miss an opportunity. So I was very conflicted about being supportive for my wife, but also to—to get the job done. And so with that, I decided to get the job done.”

Len moved into action, quickly collecting all the necessary tools to harvest his son’s cord blood and—to his wife’s and his own great relief (and for the survival of their marriage!)—even made it back to the delivery room before his son was born. Happily, Len’s son was and is healthy and has never needed that cord blood. But the blood is still saved in a flask, stored 17 years ago, by a nervous, but proud papa.

Ask Len your questions!

Q: My students enjoyed learning about your zebra fish lab. They had some questions for you:

1) Can you make a multi-colored zebra fish?

2) Do you put cancer genes in the fish, or do they already have them?

3) Do you ever feel bad putting diseases in the fish?

4) What is your favorite song to play on the trumpet?

5) What made you want to be a biologist?

6) Do you and your brother ever play music together?

7) What is the weirdest thing that has ever happened in the lab?

8) Have you ever been to the Mayo Clinic? We live in Rochester, MN and know that Mayo also has a zebra fish lab.

9) We have a student who is working on a science fair project with Zebra fish, do you have any advice for her?

1. Yes. We have some fish that are red in some tissues, green in other tissues, and also have blue muscle.

2. Fish do develop cancer. We have put human cancer genes into the fish, and the fish develop tumors.

3. The lab treats the fish with respect, and we only do our experiments with the goal of helping humans with disease.

4. I like to play the Haydn Trumpet Concerto. But also a song called I remember Clifford.

5. I have always enjoyed chemistry and biology. My two uncles were doctors, and so they got me interested.

6. Yes. We had a band in high school. The drummer in the band is now the prinicipal percussionist in the Pittsburgh symphony.

7. once a technician was monitoring for radioactivity, and the entire lab was blazing. We thought that someone must have spilled a vial with radioisotopes because the Geiger counter was very loud. Then we found out that the technician had had a bone scan that day, and it was just him and not the lab that was radioactive.

8. Never been there. My friend Steve Ekker has a wonderful lab there.

9. Always show how the fish resembles humans. Our story on ferroportin, published in Nature, 2000 is a good story for relevance. It was the first time the zebrafish was used to find a new human disease.

Q: My class has a few questions for you:

1) What is your favorite zebrafish color?

2) When did you become interested in biology?

3) Do you have any people that inspired you to do cancer research?

4) What was your pet frog’s name?

5) Some people have said that chocolate can help to cure cancer. Have you ever given the zebrafish chocolate?

6) Why do fish have the same genetics as humans?

7) How far away do you think you are from finding a cure for cancer?

- I like the green. It is very bright.

2. It was in college. I always liked chemistry, but in college I was exposed to some very good teachers and that stimulated me to do research in biology.

3. My mother died of breast cancer, so that is a motivation. My mentor in medical school was a hematologist/oncologist.

4. We actually named our two frogs after our two kids, Becky and Tyler.

5. Never give zebrafish chocolate. I doubt that it can cure cancer, but I like how chocolate tastes.

6. Most vertebrates have the same set of genes, and also they are diploid. That means that they have chromosome pairs.

7. We have a paper that is about to be submitted with a new potential therapy for melanoma. I’d like to think that we are 5-10 years away.