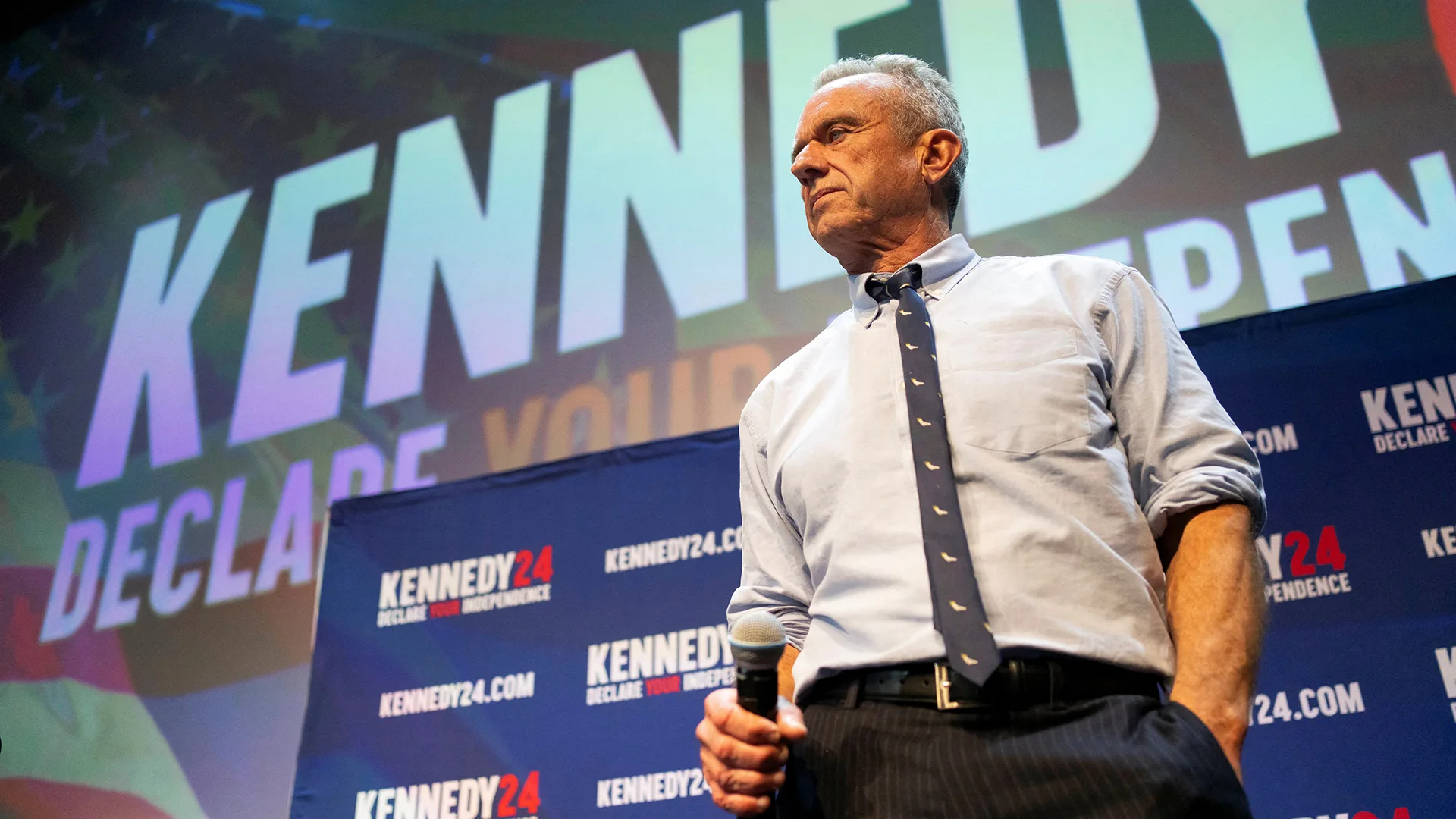

Cell Tower Deaths

May 22, 2012

30m

FRONTLINE and ProPublica investigate the hidden cost that comes with the demand for better and faster cell phone service

Cell Tower Deaths

May 22, 2012

30m

Share

The smartphone revolution comes with a hidden cost. A joint investigation by FRONTLINE and ProPublica explores the hazardous work of independent contractors who are building and servicing America’s expanding cellular infrastructure. While some tower climbers say they are under pressure to cut corners, layers of subcontracting make it difficult for safety inspectors to determine fault when a tower worker is killed or injured.

Support provided by:

Learn More

Most Watched

The FRONTLINE Newsletter

Related Stories

Feds to Look Harder at Cell Carriers When Tower Climbers Die

Labor Dept. Warns of “Alarming” Rise in Cell Tower Deaths

Anatomy of a Cell Tower Death

Safety Stand Down Called for on AT&T Projects

Built for a Simpler Era, OSHA Struggles When Tower Climbers Die

Ask a Former Cell Tower Worker

Live Chat Wednesday 1 p.m. ET: Who’s Responsible for Cell Tower Deaths?

How Subcontracting Affects Worker Safety

Methodology: How We Calculated the Tower Industry Death Rate

Jordan Barab: Why OSHA Can’t Cite Cell Carriers for Worker Safety Violations

AT&T’s Statement to FRONTLINE

In Race For Better Cell Service, Men Who Climb Towers Pay With Their Lives

Related Stories

Feds to Look Harder at Cell Carriers When Tower Climbers Die

Labor Dept. Warns of “Alarming” Rise in Cell Tower Deaths

Anatomy of a Cell Tower Death

Safety Stand Down Called for on AT&T Projects

Built for a Simpler Era, OSHA Struggles When Tower Climbers Die

Ask a Former Cell Tower Worker

Live Chat Wednesday 1 p.m. ET: Who’s Responsible for Cell Tower Deaths?

How Subcontracting Affects Worker Safety

Methodology: How We Calculated the Tower Industry Death Rate

Jordan Barab: Why OSHA Can’t Cite Cell Carriers for Worker Safety Violations

AT&T’s Statement to FRONTLINE

In Race For Better Cell Service, Men Who Climb Towers Pay With Their Lives

CORRESPONDENT Martin Smith

MARTIN SMITH, Correspondent: [voice-over] It’s one of America’s most dangerous jobs.

TOWER CLIMBER: People have no idea what we go do on a day-to-day basis to give them that service when they’re holding their cell phones.

[Twitter #frontline]

MARTIN SMITH: Tower climbers install and service cell phone antennas, ascending hundreds, sometimes more than a thousand feet.

ROBERT HALE, Former Tower Climber: People don’t understand what the danger is to tower climbing. One person drops a wrench and it’ll kill somebody.

TOWER CLIMBER: Yeah, 1,500 feet! Look at that view! We get paid for this!

MARTIN SMITH: The job attracts a certain kind of worker—

TOWER CLIMBER: This is awesome!

NARRATOR: —someone like Jay Guilford.

ROBERT HALE: He was young. He was cocky. He was never scared of nothing.

911 OPERATOR: 911 emergency.

TOWER WORKER: Yes, we’re working on a tower site. We just had a man fall from a 200-foot tower. We need an ambulance.

911 OPERATOR: OK, I’ll get them down there.

ROBERT HALE: It was not even a year. Jay ain’t even been in it a year when the accident happened.

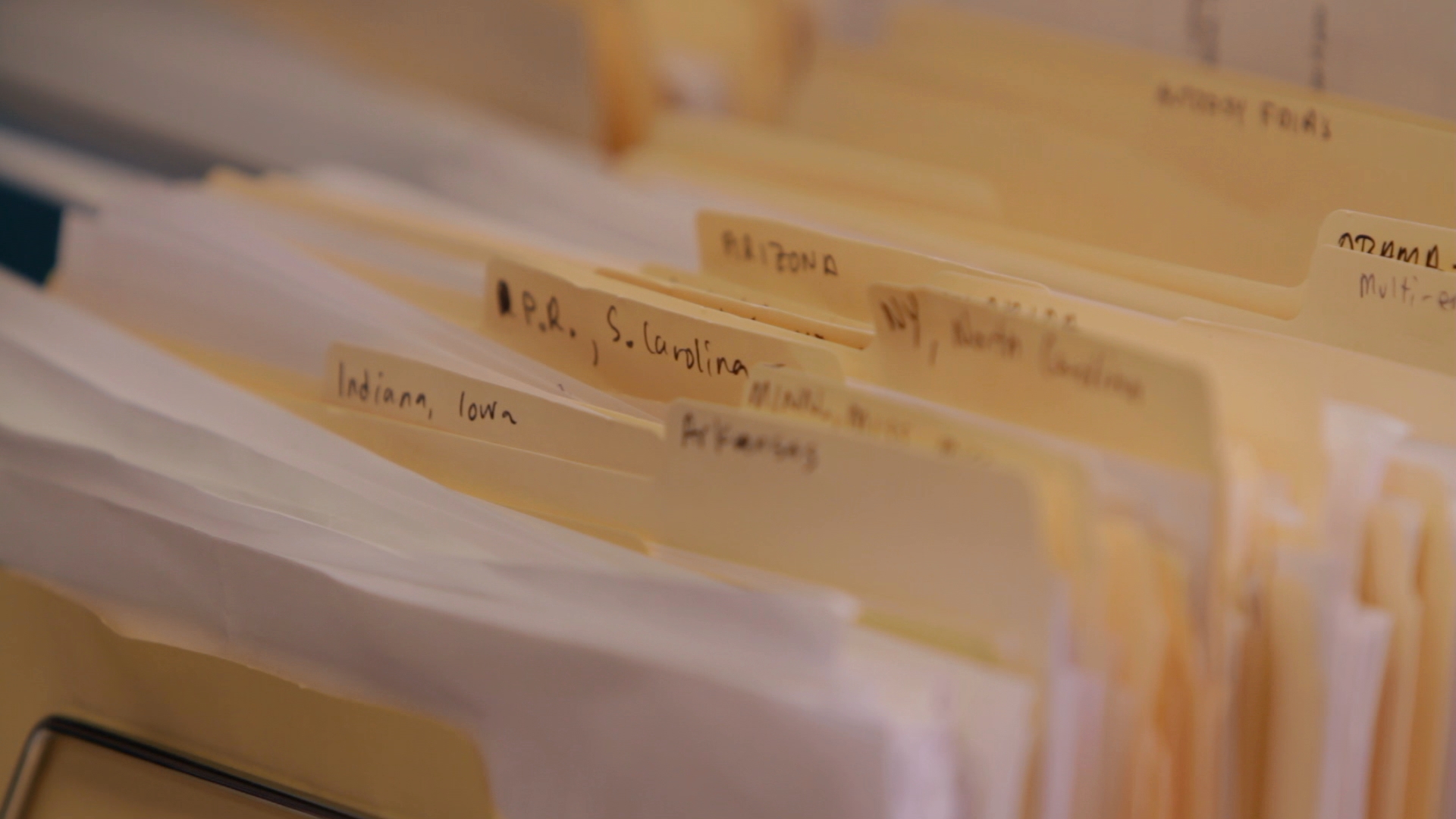

MARTIN SMITH: Guilford’s death wasn’t an isolated case. Over the last decade, other men have been falling to their deaths— North Carolina, Arizona, Kentucky, Florida, Iowa. Since 2003, there have been nearly 100 climbers killed on radio, TV and cell towers, a rate that is about 10 times the average for construction workers.

INTERVIEWEE: Jay Guilford, actually— this is what he was using when he—

MARTIN SMITH: To find out why, reporters at FRONTLINE and ProPublica investigated the 50 cell-related deaths.

INTERVIEWER: But did they address the question of responsibility for—

MARTIN SMITH: After poring over thousands of documents, we discovered a complex web of subcontracting that has allowed the major carriers to avoid scrutiny when accidents happen.

[www.pbs.org: How we reported the story]

RAY HULL, Former Tower Climber: Any of your cell phone carriers, as far as they’re concerned, safety is our issue, not theirs.

MARTIN SMITH: Ray Hull is a tower climbing veteran. Before cell phones, he worked mostly on TV and radio towers.

RAY HULL: Any major tower company knew who I was, knew who my dad was, my granddad. I’m third generation in that line of work.

MARTIN SMITH: But with the boom in cell phones, the industry suddenly changed.

RAY HULL: There was a big push for these cell companies to start expanding out and covering the dead areas, everybody trying to outdo everybody.

WINTON WILCOX, Tower Industry Veteran: Fifteen, twenty years ago, a good tower company might— might build four towers a year. Now timelines are radically different. So instead of contracts to build a tower, you have contracts to build 40 towers.

MARTIN SMITH: The increased pressure almost killed Hull.

RAY HULL: It was a cell phone tower for Nextel.

MARTIN SMITH: Hull was hired by the subcontractor and given a strict deadline.

RAY HULL: The only problem with that is, the equipment that I had to use was in Texas, and we’re in Fremont, Nebraska, about 20 hours away.

MARTIN SMITH: He was worried the drive would make him miss the deadline, so Hull called the subcontractor.

RAY HULL: They said, “We can’t change the deadline. This is Nextel’s deadline. They— the tower has to be up and completed.” We left Nebraska, and it was nonstop. We drove straight through, loaded the equipment, got back in the truck, and drove nonstop.

MARTIN SMITH: He planned to sleep back in Nebraska, but then he arrived at the work site.

RAY HULL: When we got back, there was a Nextel vehicle on site. I assumed that he was there to rattle our cage, get us to go faster.

MARTIN SMITH: Hull didn’t know it was just a technician. He felt pressured and immediately ascended the tower. We obtained the government investigation video and showed it to Hull for the first time.

RAY HULL: I’m just amazed that I’m even here. I remember hearing a loud noise.

MARTIN SMITH: A huge piece of steel broke lose.

RAY HULL: My head was jammed into the piece of steel and knocked me out.

MARTIN SMITH: Hull fell 240 feet, but his life was spared after his safety harness broke the fall.

RAY HULL: The operator pulled the wrong lever. Frankie was with me on the trip from Nebraska to Texas and back. Neither one of us was rested. And we have the end result that we do today.

MARTIN SMITH: Hull suffered severe internal injuries and is now permanently disabled.

RAY HULL: It was a bad day, or a good day, whichever way you want to look at it. I walked away from it.

MARTIN SMITH: [on camera] So a lot of time pressure— you saw that often in your in your work?

WALLY REARDON, Former Tower Climber: All the time.

MARTIN SMITH: All the time.

WALLY REARDON: We saw it all the time.

MARTIN SMITH: [voice-over] Veteran climbers like Wally Reardon say that time pressure often leads to something called “free climbing.”

WALLY REARDON: Free climbing’s anytime when a person’s climbing on a tower where you’re not connected to a fall arrest system.

MARTIN SMITH: [on camera] A catch. Basically, you’re attached to the tower.

WALLY REARDON: Right.

He’s just thinking about the shortest route there.

MARTIN SMITH: Reardon climbed towers for 10 years. Now he drives around and takes pictures of free climbing to try to draw attention to the dangerous practice, which regulations strictly prohibit.

WALLY REARDON: He’s not tied off.

MARTIN SMITH: Free climbing was involved in about half of the fatalities we examined.

[on camera] So what am I looking at here, Wally?

WALLY REARDON: We’re looking at the guy coming down. He’s disconnected right now, and as you can see, his fall arrest—

MARTIN SMITH: So he’s totally free climbing?

WALLY REARDON: He’s totally— see how fast he’s coming down?

MARTIN SMITH: Yeah. So he trips, misses one step, he’s a dead man.

WALLY REARDON: Yeah, he’s— yeah. Absolutely. That’s pretty much the way we did it, standard operating procedure.

MARTIN SMITH: So this was no secret that everybody was free climbing and that you could get your work done quicker—

WALLY REARDON: Right.

MARTIN SMITH: —and that the contractor that was your employer was happy to have it that way.

WALLY REARDON: Sure. And even the safest people I’ve worked with in the industry eventually will cave to it.

MARTIN SMITH: [voice-over] Free climbing was apparently common for the crew that Michael Sulfridge worked with. He was a high school dropout still living at home in rural Tennessee.

ROSA SULFRIDGE, Michael Sulfridge’s Mother: He wanted to be a cop, but I talked him out of that because I thought that was a dangerous job. I was afraid he’d got shot or something.

MARTIN SMITH: When he got a job tower climbing, his parents weren’t happy about that, either.

ROSA SULFRIDGE: And we tried to make him quit, but he wouldn’t. “I’ll be OK, Mom.” He had big smile on his face, you know? “Don’t worry, Mom. I’ll be OK.”

MARTIN SMITH: His mother’s fears came true. He was free climbing near the top of this tower in Kentucky and lost his balance.

RANDY GRAY, Former OSHA Investigator: Whenever he lost his balance and fell from the tower, he landed somewhere in this area here on the ground. And in this spiral wire above was one of his tennis shoes and a workbelt.

MARTIN SMITH: Randy Gray was the investigator for OSHA, the government agency that regulates workplace safety.

RANDY GRAY: Sometimes I still can’t imagine what that boy was thinking whenever he fell off that tower, that very last few seconds.

MARTIN SMITH: Gray quickly discovered that free climbing was so accepted that the crew didn’t even bother to take safety lanyards with them up on the tower.

RANDY GRAY: The lanyards were all in the back of the supervisor’s truck. Some of them were even in new packaging, never opened up. And the employees all confirmed that’s just the way they normally did things.

MARTIN SMITH: Tower Services Incorporated, Sulfridge’s employer, declined our interview requests. Gray issued the company citations that carried a fine of $143,000. Eventually, it settled with OSHA for $24,000.

We wanted to ask OSHA about additional responsibility beyond the contractor.

[on camera] If the carrier is controlling the schedule, putting pressure on the general contractor, who in turn puts pressure on the subcontractor, who—

JORDAN BARAB, Department of Labor, OSHA: We’ve had a number of situations where we think that accidents were caused by companies trying to meet deadlines and not— not— and cutting corners on safety in order to meet those deadlines.

MARTIN SMITH: [voice-over] Jordan Barab is the number two at OSHA. Although OSHA routinely fines subcontractors after accidents, it’s more difficult to go after the carriers who hire them. To do so, it must first prove the carrier is controlling the work and has knowledge of the violation.

JORDAN BARAB: Our problem in this industry is that you have these little contractors that may set off in their pickup truck, you know, driving miles across the countryside, and may never have any contact, face-to-face contact, with their contractors.

MARTIN SMITH: [on camera] But the work that they’re doing is controlled, in a very real sense, by the carrier at the top of the chain.

JORDAN BARAB: It’s very restrictive in terms of the legal requirements. Generally, it’s only useful when you actually have somebody at the site that actually is witnessing and has some control over the actual working conditions at the site.

RANDY GRAY, Former OSHA Investigator: You can see the tower over here to the left.

MARTIN SMITH: [voice-over] Randy Gray concluded that Bluegrass Cellular, the carrier in the Sulfridge case, regularly visited the company’s tower sites, so he issued citations.

RANDY GRAY: It just seems logical that whenever the carrier was here, that they had the possibility to know that these people were not tying off with personal protective equipment, just like anyone else would’ve.

MARTIN SMITH: But Bluegrass fought back, saying, “Bluegrass does not have a duty to oversee the safety of independent contractor employees working at its cellular sites.” Gray couldn’t show that Bluegrass, which also declined our interview request, was on site and watching the day Sulfridge fell.

RANDY GRAY: There was no way to prove that the carrier knew that they were up there, not tied off, and there’s no way to prove— to know that the carrier had been on the job site that day or the day before.

MARTIN SMITH: After a nearly three-year legal battle, Bluegrass won and all OSHA citations were dropped.

We discovered that the Bluegrass case was the only time since 2003 that OSHA even attempted to cite a carrier after the death of a subcontractor.

[on camera] What does this say to you, that there’ve been no citations by OSHA against any carriers?

JORDAN BARAB: It says to me that we don’t have the legal ability to do that. Legally, there’s no way we can really get to that company, the company that may— again, several levels up— that may actually own the tower.

RANDY GRAY: It is difficult because they’ve got that layer.

MARTIN SMITH: So the multi-layers protect them from liability?

RANDY GRAY: Yeah. Just through their own policy, they layer themselves away from it.

MARTIN SMITH: It protects them from getting an OSHA citation.

RANDY GRAY: Yes.

[www.pbs.org: What OSHA can and can’t do]

MARTIN SMITH: [voice-over] In the middle of the last decade, the major carriers were gearing up for the next generation of cell phones. This push was all about data, a new standard called 3G.

AT&T had merged with Cingular to form the largest cell company at the time.

ED REYNOLDS, Fmr. President, Network Services, AT&T: We had this huge slug of work that was occurring in ‘05 and ‘06.

MARTIN SMITH: Ed Reynolds is the former president of network services at AT&T. Before retiring in 2007, he was charged with combining two distinct networks into one.

ED REYNOLDS: It would be like taking a 747 with all of its engines, and while it’s in flight at 35,000 feet, you’re going to change all four engines into one huge engine and not lose a foot of altitude.

MARTIN SMITH: But that was only the beginning.

ED REYNOLDS: And then the iPhone hit, and we knew that it was going to be a success. We were confident it would be a success. But it was a game changer, if you will.

NEWSCASTER: Well, as you can see, we’re on 5th Avenue in front of the big Apple store—

MARTIN SMITH: The success meant that data usage far exceeded what AT&T had predicted.

NEWSCASTER: Here is the giant throng—

MARTIN SMITH: Its network wasn’t ready.

BOB EGAN, Cell Network Analyst: AT&T knew that it was in trouble and that it had to get very aggressive on expanding their network footprint, especially around capacity.

MARTIN SMITH: By 2008, AT&T was pouring billions of dollars into tower upgrades. And for Phoenix of Tennessee, an AT&T subcontractor, that meant one thing.

KYLE WAITES, Owner, Phoenix of Tennessee: Work. Lots of work.

MARTIN SMITH: But to get that work, Phoenix had to go through a middleman.

KYLE WAITES: We don’t deal direct with AT&T. We do work for the vendors, the turf vendors.

MARTIN SMITH: “Turf vendors” are large firms, like General Dynamics or Bechtel, that AT&T relies on to manage work on thousands of tower sites across the country. The turf vendors, in turn, subcontract to companies like Phoenix. And in 2008, Phoenix also sent much of its work to a smaller affiliate, a company called All Around Towers.

KYLE WAITES: I would make the phone calls, open the door. Once I got them in, they pretty much took it from there.

ROBERT HALE, Former Climber, All Around Towers: And then All Around Towers hired their own crew members, their own people. It didn’t matter if they had experience or not.

MARTIN SMITH: Like Jay Guilford. He kicked around between part-time jobs. He was a mover. He delivered pizzas. But after his second child was born, he needed something better. All Around Towers was offering a full-time job at $10 an hour.

BRIDGET PIERCE, Jay Guilford’s Fiancee: That’s when he filled out the application, came back out, said he had a job, and they gave him a $600 check and had a plane ticket for him to leave, like, the next day.

MARTIN SMITH: Guilford, with no prior experience, was suddenly thrown into one of the biggest building projects the tower industry had ever seen.

BRIDGET PIERCE: Even in the wintertime, there was ice on the towers. And he would tell me he would have to literally beat ice off of the pegs to climb up the towers, which I did not find that very safe.

MARTIN SMITH: But his cousin and co-worker says Guilford wasn’t scared.

ROBERT: He enjoyed it. I mean, it was— it give him a rush that was unreal. Jay, I mean, he just— he loved the job.

MARTIN SMITH: It was May 2008 in a rural corner of Indiana.

WORKER: We just had a man fall from a 200-foot tower. We need an ambulance.

911 OPERATOR: I’ve got units en route down there.

BRIDGET PIERCE: Jay’s dad called me, and that’s when he told me that he had fallen off the tower. I freaked out and screamed and— just screamed and screamed.

MARTIN SMITH: Guilford fell when he was rappelling down the tower using the wrong kind of rope without a safety line. One witness said he was horsing around, his co-workers on the ground cheering him on. His rope was attached to a broken hook that popped off the tower. And it turns out, an autopsy showed that he had recently smoked marijuana.

KYLE WAITES: Do I feel responsible to a degree? I think everybody does that was involved with it. I think all of the— I think the turf vendor does and I think everybody does anytime somebody dies. I was not the guy who put the man in, the crew leader in charge.

MARTIN SMITH: Waites puts most of the blame on Guilford for breaking safety rules and on All Around Towers for the broken equipment and lack of supervision.

KYLE WAITES: Once you leave men alone, the men have to police themselves. The man in charge has to be the sergeant. We can’t hold the hands of everybody 100 percent of the time. It’s impossible.

ROBERT HALE: If that equipment is checked when it comes off that truck or trailer, it should have never happened. When you’re allowed to do something that is strictly unsafe, then something’s wrong up the line somewhere.

MARTIN SMITH: OSHA cited Phoenix of Tennessee, the parent company of All Around Towers, for the broken equipment. The fine was $2,500. The case was closed.

But OSHA missed the bigger picture. Our investigation found that 11 climbers working on AT&T projects died as the company built out its network between 2006 and 2008. That’s more than all the other major carriers combined.

AT&T took notice.

KYLE WAITES: AT&T made everybody have a stand-down, discuss the deaths, why it happened, what will happen to you if you get caught free climbing. They required that of every single turf vendor nationwide. It didn’t matter who you were, where you were at. You had a stand-down.

MARTIN SMITH: [on camera] So they said, “Let’s have a stand-down. Let’s stop work and figure out what the truth is.” What did they figure out?

CRAIG LEKUTIS, Publisher, WirelessEstimator.com: I don’t know if they figured out anything, quite frankly.

MARTIN SMITH: [voice-over] Craig Lekutis is an industry watchdog and safety advocate.

CRAIG LEKUTIS: I think what they did, it was, “Hey, we’ve got to pay more attention to safety” because most of those accidents, I believe, during that period of time were accidents that were caused by the worker not tying off 100 percent.

MARTIN SMITH: [on camera] It sounds like a pretty flimsy resolution.

CRAIG LEKUTIS: It is. It didn’t have the impact of if carriers would have said, “Hey, we’re stopping all work. We’re going to figure out and we’re going to solve this problem.” I think a lot of times, it’s more lip service than it is a real desire to be concerned about the safety of this industry.

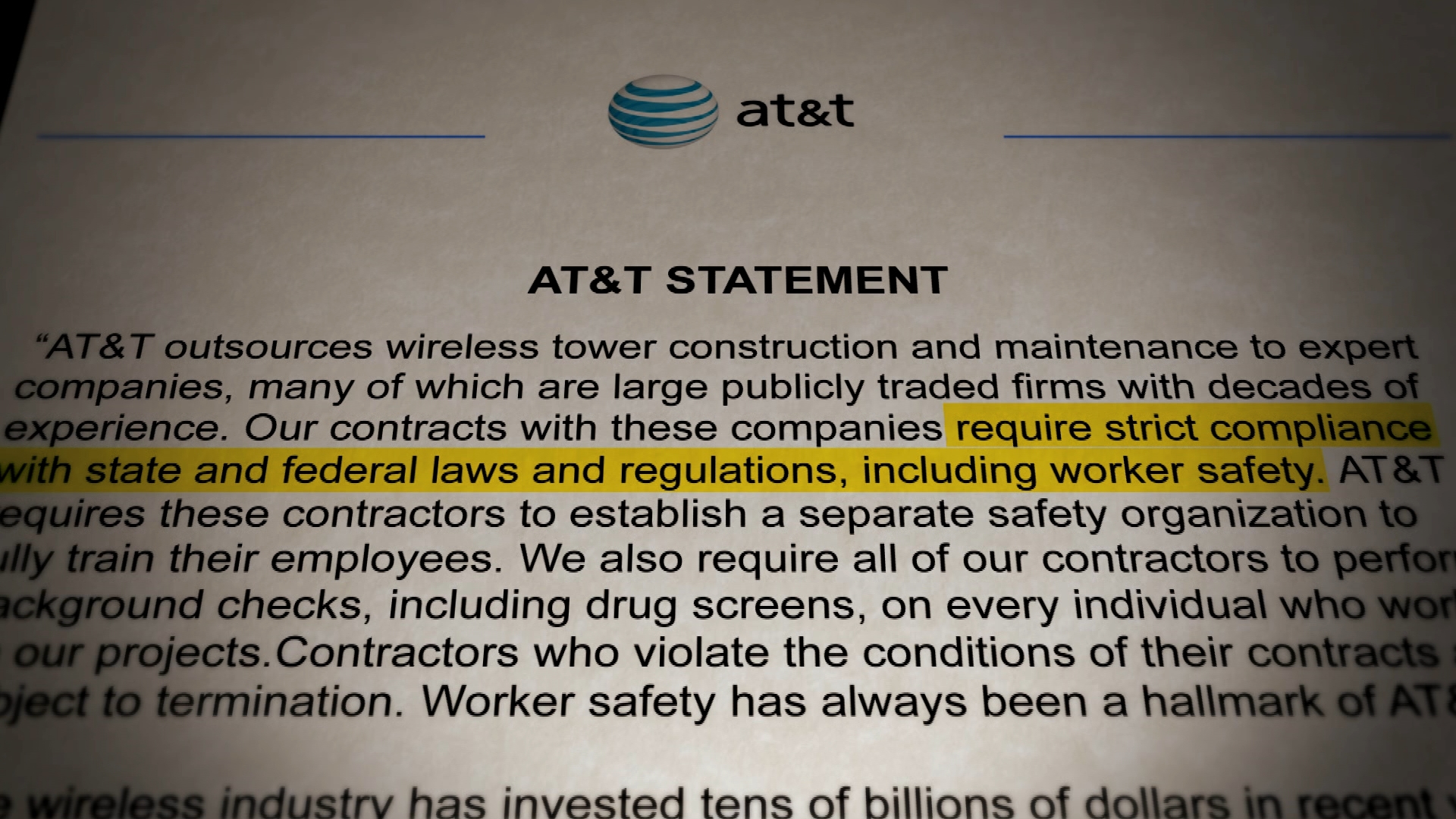

MARTIN SMITH: [voice-over] AT&T declined our request for an interview. In a statement, the company wrote that its contracts “require strict compliance with state and federal laws and regulations, including worker safety” and that “worker safety has always been a hallmark of AT&T.”

[www.pbs.org: Read the statement]

Guilford’s fiancee, Bridget Pierce, thinks that no one ultimately took responsibility for Guilford’s safety.

BRIDGET PIERCE: I believe that everybody that is involved should be held accountable— AT&T, the contractors, General Dynamics, and the smaller companies that are subcontracted out. Everybody in this process should be held accountable for and have to pay fines and have regulations that they all have to live up to.

MARTIN SMITH: After Guilford died, the foreman for All Around Towers disappeared and was never questioned by OSHA. The company quickly went out of business, but two of its owners, who declined interview requests, then started another company that continues to do work in the industry. That doesn’t surprise those who study subcontracting.

DAVID WEIL, Economics Prof., Boston University: The problem of focusing the enforcement attention at the bottom, at the small subcontractor, is a little bit like the old game of Whac-a-Mole. You can enforce your OSHA standards on that individual contractor and hit the mole, but there are a lot of other contractors that are going to pop up.

If we want to improve conditions in a workplace like towers, we have to think about the system that generates fatalities.

MARTIN SMITH: In the tower industry, that system is increasingly built around the turf vendor. AT&T relies on them almost exclusively. Sprint is also starting to.

ED REYNOLDS, Fmr. President, Network Services, AT&T: Turfing does save time and money. In the wireless business, particularly when something like an iPhone that drives data usage out the roof, you need to respond quickly. The more of that administrative stuff you can have out of the way and go right to work on doing what you need to do, adding capacity to the network, reconfiguring the network, turfing’s a benefit.

MARK HEIN, Construction Manager: It’s good sense for the— for the carrier to do it. And it’s good for the turf vendor because they’re making a lot of profit off the project. But it’s not good for the person down— when it gets to the field, where the work has got to be done.

MARTIN SMITH: Mark Hein has worked for several turf vendors. He says the additional layer of subcontracting means those at the bottom are forced to accept less money.

MARK HEIN: There’s a lot of good companies that won’t work for them because the money’s not there. So rather than paying this amount to this guy, who’s really qualified and been in the business, got— has a great reputation, they hire this person over here because he’s available right now and he’ll do it for what we want him to do it for.

MARTIN SMITH: After starting a new job last year, he was shocked by the subpar crews he found on his first round of inspections.

MARK HEIN: When I went out as construction manager, I shut down every project I had working. They didn’t have COMTRAIN training. They didn’t have RF training. They didn’t have their hardhats. They didn’t have safety glasses. They didn’t have safety gear.

MARTIN SMITH: Most surprising to Hein, many of these crews weren’t even hired or approved by the turf vendor.

MARK HEIN: They were working for a sub of a turf vendor— you know, a couple subs down the line.

MARTIN SMITH: But because of the way OSHA regulates the industry, turf vendors, like carriers, are rarely held responsible after accidents.

MARK HEIN: I wouldn’t say that the turf vendor doesn’t know. I think the turf vendor just turns a blind eye to it because his contract is with subcontractor B. It’s his responsibility.

WINTON WILCOX, Tower Industry Veteran: By the time we get to the actual person with a tool in their hand, we have significantly reduced the financial benefits. And we have put three or four layers of communication problems into the intended final results.

MARTIN SMITH: Chris Deckrow owns a small climbing company in Michigan that typically works at the bottom of a chain of contractors.

CHRIS DECKROW, High Elevation Rescue and Maintenance, LLC: The good companies are going out of business because they can’t afford their safety. They can’t afford their insurance. They can’t afford their workmen’s comp.

MARTIN SMITH: Deckrow showed us what’s left over for him after each contractor, especially the turf vendor, takes a big cut.

CHRIS DECKROW: AT&T pays the turfer $187 to install a remote radio head. The turfer then takes the contractor and pays them $93. I’ve seen as low as $40 to $50 and been paid $40 to $50 dollars to install that same item.

MARTIN SMITH: Deckrow says the pricing has forced him to make hard decisions. He drives his trucks more than 100,000 miles a year without changing the tires. And he’s cut his safety budget.

CHRIS DECKROW: This day and age, everybody’s faced with the money versus safety. Whether they’ll admit it or not, everybody’s had to cut back on something. We would love to replace every year, every two years, new harnesses and new safety gear for all our guys. It’s not in the budget. But this is stuff they have to wear every day in order to live through the day.

My climbing harness, it’s got to be around four or five years old. It’s older than we allow in the field, but it’s my personal harness. I wouldn’t do it with any of my guys.

MARTIN SMITH: Deckrow said he’s considering closing his company down rather than paying his climbers less or cutting the safety budget even more.

DAVID WEIL, Economics Prof., Boston University: The carrier sets many of the conditions that ultimately affect injuries and fatalities on that work site by setting the amount of money that the people who actually do that work are going to be paid for that work, and therefore, how much they can invest in things like health and safety and paying high enough wages to attract people who might be competent to do that work.

MARTIN SMITH: For carriers, the responsibility for safety ultimately rests with the contractors.

ED REYNOLDS, Fmr. President, Network Services, AT&T: You can take the captain of the ship approach and say if there was a fatality in a subcontractor working two levels down under a turf vendor who’s working for a network who’s working for AT&T Mobility— I mean, you can say that Randall Stephenson is responsible, you know, because Randall Stephenson’s the CEO of AT&T.

But what impact saying that Randall Stephenson is responsible for that would have on the eventual safety of future crews— I think that’s too far to connect. At what point do you connect? I don’t know.

MARTIN SMITH: In the course of our investigation, we obtained this private letter to OSHA from the subcontractors trade group. In it, they urged OSHA to go after carriers and turf vendors that hire unqualified contractors, warning that otherwise, quote, “fatalities are going to continue.”

But three years later, we found out that OSHA doesn’t even track which carriers are connected to fatal accidents.

[on camera] At this point in time, you don’t collect data on the carriers.

JORDAN BARAB, Department of Labor, OSHA: We don’t.

MARTIN SMITH: And is that something that you should be doing?

JORDAN BARAB: It’s something we could do. Again, it’s a lot of work to try to trace things up to the ultimate owner. But it’s— it would probably not be a bad idea for us to do that.

MARTIN SMITH: Is it that much work? Don’t you just have to ask the subcontractor?

JORDAN BARAB: Well, the subcontractor may not know who the ultimate owner is. The subcontractor may know the general contractor that they’re working for, and the general contractor then may know who— and again, we’re talking about sometimes multiple levels here.

MARTIN SMITH: But it’s only two or three phone calls and you would know who the carrier was.

JORDAN BARAB: Perhaps.

MARTIN SMITH: Were you aware before we shared this information with you that AT&T had a higher incidence of fatalities?

JORDAN BARAB: I’m not sure, but I don’t believe so.

MARTIN SMITH: [voice-over] AT&T’s letter to FRONTLINE and ProPublica pointed out that tower fatalities across the industry have declined since 2008. There were no deaths on AT&T jobs last year, even though the carrier said its workload increased.

And that workload is going to get even bigger. The competition to build the next generation network, 4G, has already begun.

BOB EGAN, Cell Network Analyst: We have Windows competing with Android, competing with Blackberry, competing with iPhone. And people have high expectations. I think we’re on the cusp of a pretty massive build-out across all of the major networks, in particular Sprint, Verizon and AT&T, to deliver these much higher-speed networks.

MARTIN SMITH: That worries veteran climbers who remember the last big build-out.

CHRIS DECKROW, High Elevation Rescue and Maintenance, LLC: We’re going to have a bad year as an industry because they’re going to go on a big push and your $10-an-hour pizza guys that are now climbing for you because you can’t afford otherwise are going to start skipping steps.

RAY HULL, Former Tower Climber: It takes years and years of training to know the safety of your equipment. There’s guys out there now that are foremen within months of working, starting a job. That’s ludicrous!

WINTON WILCOX, Tower Industry Veteran: There’s no time to season these employees. There’s no time to mature them. There’s no time to train them. So we have increasingly less experienced, less trained, less capable individuals doing increasingly large projects at increasing pressure and with decreasing compensation.

MARTIN SMITH: And there will always be more workers like Michael Sulfridge, who was willing to climb towers for $10 an hour and just happy to have a job.

ROSA SULFRIDGE, Michael Sulfridge’s Mother: These young men are willing to please. You know, whatever the foreman tell them, they’re going to do it. It’s a money business. It’s, “Get the job done, we’re going to get a big check.” Yeah. If you fall— oh, well.

CHRIS DECKROW: If we’re not properly maintained or trained, then people will die. And it’s only a matter of time.

CELL TOWER DEATHS May 22, 2012

WRITTTEN AND PRODUCED BY Travis Fox

REPORTERS Ryan Knutson, FRONTLINE Liz Day, ProPublica

EDITED BY Maeve O’Boyle Tom Behrens

SENIOR PRODUCER AND CORRESPONDENT Martin Smith

CO-PRODUCERS Habiba Nosheen Ryan Knutson

ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Jennifer Pritheeva Samuel

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY Travis Fox

ORIGINAL MUSIC Joel Douek

ADDITIONAL CAMERA Habiba Nosheen

ADDITIONAL EDITING Steve Audette Mark Dugas

ONLINE EDITOR/COLORIST Jim Ferguson

SOUND MIX Jim Sullivan

ARCHIVAL FOOTAGE CNN ImageSource Thought Equity Motion Kantar Media Joshua Walker Jodi Anderson

FOR PROPUBLICA

SENIOR EDITOR Robin Fields

GENERAL MANAGER Richard Tofel

MANAGING EDITOR Stephen Engelberg

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paul Steiger

FOR FRONTLINE

DIRECTOR OF BROADCAST Tim Mangini

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF BROADCAST Chris Fournelle

ON-AIR PROMOTION PRODUCER Missy Frederick

ON-AIR PROMOTION EDITOR John MacGibbon

POST PRODUCTION EDITORS Michael H. Amundson Jim Ferguson Mark Dugas

ASSISTANT EDITOR Eric P. Gulliver

POST PRODUCTION COORDINATOR Megan McGough

SERIES MUSIC Mason Daring Martin Brody

DIRECTOR OF AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT Pamela Johnston

SENIOR PUBLICIST Diane Buxton

ONLINE ENGAGEMENT COORDINATOR Nathan Tobey

SECRETARY Christopher Kelleher

EDITORIAL SECRETARY Katie Lannigan

COMPLIANCE MANAGER Talya Feldman

CONTENT MANAGER Lisa Palone

LEGAL Eric Brass Jay Fialkov Janice Flood Scott Kardel

CONTRACTS MANAGER Lisa Sullivan

UNIT MANAGER Varonica Frye

BUSINESS MANAGER Tobee Phipps

DIGITAL RESEARCH ASSISTANT Jason Breslow

ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS FOR DIGITAL Gretchen Gavett Azmat Khan

PODCAST PRODUCER/REPORTER Arun Rath

DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIST Bill Rockwood

DIGITAL REPORTER Sarah Childress

SENIOR DIGITAL PRODUCER Sarah Moughty

WEBSITE DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY Entropy Media, LLC

DIRECTOR OF NEW MEDIA & TECHNOLOGY Sam Bailey

DEPUTY STORY EDITOR Carla Borras

COORDINATING PRODUCER Robin Parmelee

SENIOR EDITORIAL CONSULTANT Louis Wiley Jr.

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER SPECIAL PROJECTS Michael Sullivan

DIRECTOR OF DIGITAL MEDIA/SENIOR EDITOR Andrew Golis

MANAGING EDITOR Philip Bennett

SERIES MANAGER Jim Bracciale

SERIES SENIOR PRODUCER Raney Aronson-Rath

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER David Fanning

A FRONTLINE production with RAINmedia

©2012 WGBH EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

FRONTLINE is a production of WGBH/Boston, which is solely responsible for its content.

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.