♪♪

Norberg: Human beings thrive on work.

Independent of money,

work brings us satisfaction,

fulfillment, and happiness.

It's indisputable.

Work and happiness are deeply linked.

Norberg: But for these Americans,

finding sustainable work is a daily challenge.

There are 47 million Americans who live in poverty

and survive only with the aid

of a complex system of public assistance.

But this well-meaning system

can have devastating consequences.

Chris: There's so many good people

who are just in an unfortunate circumstance

who just get left behind.

Welfare was, like, the last option for me.

Richard: People would look at me in disgust.

I want to explain to them,

"I'm going through something right now.

This isn't me," you know, "Understand."

Sawhill: None of us likes the idea

of supporting people who can't support themselves,

and the poor, most of all,

don't like the idea of being on the dole.

Once you're poor, there's no getting out of it.

I don't care.

There's no getting out of it.

You know, a lot better welfare system

would be one that allowed people

to try to get out without penalizing them.

The real cost of welfare is the human cost of welfare.

It's not the dollar cost.

Norberg: Each year, the financial cost mounts,

as does the human cost of welfare.

♪♪

♪♪

♪♪

Each month, here in Washington D.C.,

the Bureau of Labor Statistics issues its report

on the number of Americans who have gone to work.

Work is vitally important to Americans

and to everyone everywhere.

It's not just a paycheck.

It's an essential component of our self-worth,

our confidence, our happiness.

I'm Johan Norberg, a writer and analyst from Sweden,

and I've long been interested in the dynamic connection

between work and happiness.

♪♪

Dignity is found in a hard day's work,

on a farm, in a factory,

in a shop, or at a desk.

But what happens when a person can't find work?

Here in the United States

and in developed countries all around the world,

governments have created welfare programs.

Their admirable intention is to help the poor

by providing a safety net

to help get people back on their feet.

But here in the U.S.,

research suggests that the various programs

in the state and federal system we call welfare

often hurt the people they are designed to help.

♪♪

We will meet real people whose dreams and aspirations

are defined and confined by a well-meaning system.

Their stories represent millions of others

for whom the safety net has become a trap.

Their challenges and the odds they face

are daunting, often insurmountable.

♪♪

It reminds me how important it is

that I need to be self-sustaining,

that I need to be independent.

Norberg: Chris is a divorced mother to four daughters,

one of whom was born with cerebral palsy

and requires constant care.

She seeks the independence she once had through a career,

but the system seems to work against her.

Monique: I just expect more out of life and better.

I didn't wake up saying, "I wanted to be on welfare"

because welfare was, like, last option for me.

Norberg: Monique was born into poverty.

She recently married the father of her youngest child

but has discovered that marriage comes

with a very real financial penalty

when one is on welfare.

Currently unemployed,

she's determined to overcome

and find work to support her family.

I've been on welfare practically all my life.

You know, growing up, before I was born,

welfare existed in my family.

Norberg: Angel is a single father of two growing children.

He's a third-generation welfare recipient,

suffered parental abuse,

and lived a life of crime as a young man.

With all that behind him now,

he still feels stuck in the system.

Richard: In prison, they take you, and they shave your head.

They give you a prison outfit,

and they give you a number.

They tell you, "Learn this number.

This is who you are."

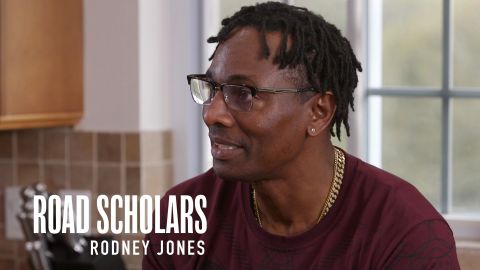

Norberg: Richard is resetting his life after 20 years in prison.

Raised in poverty by drug-addicted family members,

Richard's life was immersed in crime

from an early age.

He is now determined to turn his life around.

All of these people search for work and for happiness.

All of them face obstacles

built into the American welfare system.

♪♪

Of all the books and articles I've read on the welfare system

and of the importance of work for happiness,

none are more relevant than those by Charles Murray.

Beginning with his landmark book

"Losing Ground" in 1984,

Charles continues to write

about the American welfare system.

How are you? Yeah.

Beautiful place. Come on in.

Thank you.

A wise man wrote

that the problem with the welfare system

is not what it costs but what it buys,

and I think that was you.

Oh, it's a nice line, isn't it?

Yes, It's much easier to say,

"Let's give people money"

than "Let's give people satisfying lives."

But you know what? That should be.

That should be the goal of social policies.

Money is the easy part, and so we go with that.

But this is something we often miss when we --

we're in politics,

when we talked about the welfare system

because it's easy to target a specific material level.

I think they're talking way too much about money,

and they aren't talking enough about human flourishing.

This is my reading of the data, as well.

When I've looked at life satisfaction in Sweden,

you can see that income is not the decisive factor.

On no level, it's the decisive factor.

We make a big mistake, a huge mistake,

if we expect happiness

to correlate directly on a one-for-one basis

with the amount of money you're making.

Wasn't this the classic puzzle in social psychology?

Why is it that lottery winners

aren't much more happy than the rest of us?

Not only are lottery winners not more happy,

it is a really good way to ruin your life

if your life is not grounded in other things.

The happiest lottery winners keep on working.

♪♪

Has America's focus on material prosperity for the poor

actually come at the expense of human happiness?

This large granite building in Washington D.C.

houses the United States Department of the Treasury.

This is where the government collects all the taxes,

pays all its bills,

and generally manages the country's economy.

In fiscal year 2015,

the federal budget include $3.8 trillion in expenditures,

around $12,000 for every American man, woman, and child.

Around $1 trillion was spent

on approximately 86 different programs,

making up what's called the welfare system.

Politicians and experts have differed

on the increases and decreases in the level of poverty,

but all agree that tens of millions of Americans

are still considered poor.

♪♪

Chris lives in a small town in northern Washington.

Originally from Kansas,

Chris met and married her husband

after graduating college.

They had four children

while running a construction business together,

but life has been a challenge.

Her second child, Madrona, now 13 years old,

was born with cerebral palsy,

and 3 years ago, Chris was diagnosed with cancer.

It's a little too hot?

The money that we were using to care for Madrona

was running out.

Is your chair getting too hot?

Let's get out of here. [ Grunts ]

Yeah, the black gets pretty warm.

That's when we turned for assistance,

and at the same time,

that's when I was diagnosed with breast cancer,

and then six months later,

the kids' dad filed for divorce.

So the domino effect of all of those things,

and, now, here I am, three-years-post all of that,

still on public assistance

and really just now feeling like I'm getting my bearings

in terms of,

"Okay, how will I transition out of this place, now?"

Mommy, where's the keys?

The keys are... over there.

Both of my parents were very hard workers.

They had a value around work integrity

and providing for your family.

[ Engine starts ]

I want to support my family independently,

have my own place where I pay my own rent,

I have work.

Brooks: When you take work out of people's lives,

there's a hole that's produced, obviously,

but it's not just a hole in their time.

Norberg: Arthur Brooks,

president of the American Enterprise Institute,

writes and speaks extensively

on what he calls "earned success."

526.

Brooks: The real hole is created in their sense of dignity,

in the sense of worth and the sense of meaning.

People are created to create value.

Earned success is the concept

that you're creating value with your life,

and you're creating value in the lives of other people.

Norberg: Chris wants to work,

but can she afford to endanger her benefits?

How much I work generally will decrease my benefits.

There's a certain amount

where I, myself, will lose Medicaid insurance

which is important

because I have a history of cancer.

It's very complicated

to figure out what the sweet spot is.

Norberg: The way the system works,

Chris would lose more benefits

if she worked an entry-level job

than she could compensate for with earned income.

Chris: Generally, what I come up with

is if I want to support my family independently,

have my own place where I pay my own rent,

I have work, you know,

I need to go from where I'm at now

to around $60,000 a year.

♪♪

Chris: Hi, Amber. How's it going?

How was the library? Good.

Murray: When we're talking about how to fix the welfare system,

let's start with the reality of how miserably it's run.

The amounts of time that you have to spend

dealing with welfare bureaucracy if you're a recipient,

the complex rules,

which make it next to impossible

to understand how you could get out of it.

I mean, "How many hours can I work

without losing my benefits?

What are the parameters?"

Norberg: Social scientist Isabel Sawhill

is a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution

and served in the Clinton Administration.

She has spent decades studying welfare and its effects.

There's no question that there are

certain disincentives built into our programs

so that if you earn more money

that you're going to lose some benefits.

Chris: You go to the office,

and you see the population of people

who are working with this.

Everyone just looks so worn out, and I get it.

Like, it just wears you down.

If I'm going to be worn down,

I'd like it to be because I'm working,

not because I'm, you know,

running around to different appointments.

Norberg: Chris receives assistance from five different programs,

all run by separate agencies --

TANF, Medicaid, Child Support, SSI, and SNAP.

Each carries distinctive rules and regulations

along with separate paperwork, appointments,

phone calls, and deadlines.

These rules are very complicated.

They're tough.

And I do not blame a welfare recipient

who does not know all the rules.

That doesn't even make sense.

See, this is why I just want to be off of the whole thing.

Every time I go to my case manager

and I say that --

I say, "I need to transition off.

This is maddening.

I don't have time for this,"

she really warns me against it.

All right.

Yes, ma'am?

Is it time for lunch? It is time for lunch.

I was just putting my stuff away.

Doar: And the problem is that that leads to people

not working as much as they'd like to

or as much as they should.

So it's bad for families, it's bad for children,

it's bad for individuals.

Norberg: Robert Doar is former commissioner

of New York City's Human Resources Agency.

He has an inside perspective

on why he believes the welfare system is broken,

and what he considers might be done

to address the problems.

Doar: Whether it's child care or public health insurance

or food stamp benefits or tax credits,

we run our programs in this country

through all these different separate silos of programs.

And so for a recipient of assistance,

they're moving around from one to the next to the next,

and they don't don't really know or understand

why the rules are different.

♪♪

Norberg: Whether or not Chris will succeed

depends largely on the policies executed

by the people who work in this building.

Here at the Department of Health and Human Services,

there are more than 80,000 full-time employees

administering the programs designed to aid America's poor.

But despite this army of people and $1 trillion in resources,

the unintended consequences of those programs

can prevent the poor from getting back on their feet.

One big problem is the welfare cliff.

If we follow earnings as income increases,

food stamps, housing, and TANF begin to bottom out,

leaving recipients in a worse financial position.

Even if a recipient keeps working,

the cliffs continue as income rises,

making the jump to work financially risky.

To make matters worse,

it is unclear exactly when benefits are lost.

The rules change by state, legislation, income,

and number of dependents.

In a welfare-cliff situation,

each additional dollar of earnings,

each opportunity for a promotion,

each additional number of hours

becomes a balancing act

that a welfare recipient has to decide,

"Do I want that

or will I lose too much in childcare assistance?"

or, "Will I lose too much

in public health insurance coverage?"

or, "Will I lose too much in cash supplemental aid?"

And that kind of dynamic is not healthy,

and it's not helpful.

You know, a lot better welfare system

would be one that allowed people

to try to get out without penalizing them.

♪♪

[ Siren wails ]

♪♪

She turned it off. Sam.

Stephanie: I mean, she hit snooze. I told you. Get up.

You turn off your alarm?

Norberg: Like his mother and grandmother before him,

Angel is on welfare.

Why? You've got to start getting up, Sam.

It's already past 7:00.

As a single father with two children,

he receives a variety of state

and federal government benefits.

Nat, start getting up. Come on.

Angel: Usually a father would say,

"I want my son to grow up like me.

I want my son to grow up like his father."

No, not at all.

Because the way I grew up

and the things I've done in the past...

If you're going to school by yourself, that's fine.

If not, I got to walk Samantha.

...No. It hurts me to say,

"I don't want him to grow up like me."

I want him to grow up and be his own man.

I want him to be better than me.

-All right. We ready? -Yeah.

Norberg: Angel wants to work to support his children,

but if a minimum wage job is the best he can get,

it may not be worth it.

It doesn't make sense to get a minimum-wage job.

Might as well stay on welfare

because having a minimum wage job,

it's like the same thing as being on welfare.

It's little money.

Norberg: Angel feels stuck in the system.

His long-term girlfriend, Steffani, tries to help.

I've got to call the housing to find out

what's going on with the transfer and everything.

Steffani: Okay.

Woman: Section 8 applications.

Yo, you've got to go with me

to the child support to straighten this out.

Steffani: They said you have to go down

and file for a modification,

and they should stop it right away.

That's what they told me.

Angel: Every paper that I've got on top of my shelf right here,

is nothing but bills and bad news.

There's no good news right there, none.

Just bad thoughts go through my mind.

Woman: Case number and county?

Angel Rodriguez.

I'm calling from Bronx, New York.

Doar: It's about helping people

be as self-sufficient and independent

as they want to be

and, unfortunately, our programs right now

are not encouraging that sufficiently.

Woman: N as in Nancy, Q as in queen,

2-3-2-4-8,

P as in Peter, 1, or T as in Tom?

No. T one.

T-1.

T-1, like... T as in Tom, yes.

T as in Tom. I'm sorry. Okay.

Angel: Every time you go in for an appointment,

they should tell you about jobs.

They should have listings on the wall,

instead of listing,

"Do you need food stamps? Do you need cash assistance?"

Things like that.

It's ridiculous.

No, no. Wait. Okay. Woman: Thank you.

Well, I was speaking to someone

like, maybe, no more than 5 minutes ago,

and she was helping me,

but I forgot to give her this account number.

Doar: I found, in going around the country

and talking to low-income recipients

of forms of assistance,

They say,

"They're good at giving me assistance financially,

but they don't help me get a job."

Once I start working,

welfare's going to send me a letter

saying the same thing.

"We're going to cut you off."

But I've got to go to work,

so I'm not thinking about what welfare thinks right now.

I'll worry about that later.

Hold on. Hold on. Here. Here.

Ask him. They can't talk to me.

All right.

Can I have someone speak for me, please?

Because this is just aggravating me.

I'm sorry.

Brooks: Today, in America,

we have a bottom half of the population

that effectively has an economic growth rate

that's about zero.

We can't stand for that.

How much do we get every two weeks from...

You? P.A.?

It's just, it's always a struggle.

It's always something else that we can never catch up on.

Brooks: Look around.

We see that the poor in this country

are not having an increasing standard of living.

You find that the bottom 20% of the income distribution

has about a third-less likelihood

of getting to the middle class or above,

as it did in 1980.

Mobility is kind of stagnant in this country,

and that's a big problem.

Norberg: A life on public assistance

has greatly affected Angel's relationship with Steffani,

and he doesn't want to drag her down with him.

Once you're poor, there's no getting out of it.

I don't care.

There's no getting out of it.

Don't waste your time being with me.

[ Crying ] It's why I tell you these things, man.

I don't want to drag you down,

don't you understand?

Listen. Stop.

You know, you're really intelligent.

You're beyond freaking smart, man.

Being poor doesn't make you any different of a person.

It doesn't.

Angel, it doesn't matter. I could do it alone.

I could do it with you.

I could do it with anybody else.

[ Normal voice ] Steff, reality is

you shouldn't be with someone

that's not really doing much for themselves.

Not that I'm lazy or anything like that,

it's just I'm stuck.

You don't want to be stuck with me.

I'm not. I'm helping you get unstuck.

[ Crying ] It's just this life is embarrassing.

I don't like it.

♪♪

Norberg: Poverty produces stress,

and stress takes a toll on relationships.

Inadvertently, welfare has magnified the effects,

penalizing marriage

and encouraging single parenthood.

Charles Murray has strong feelings

about the impact of welfare on the family.

Norberg: Do you think it's fair to say

that welfare programs

have undermined the family as an institution

by discouraging marriage?

Absolutely, they've undermined marriage

as an institution.

It has contaminated, corrupted, undermined,

eroded the social penalties and rewards

that have made communities function for millennia.

Sawhill: We have had growing numbers

of single-parent families in the U.S.,

and they tend to be poor.

They're four or five times as likely to be poor

as a family that has two parents.

But now, single parent families

are about a third of all families

and still growing.

We have a much more costly

and serious problem on our hands.

Norberg: Poverty is caused by a variety of factors,

but there are ways to reduce the risk.

Sawhill: Poverty rate right now

is about 15% of all Americans being poor.

If you graduated from high school,

if you worked full-time,

and if you didn't have children

until you were in a stable two-parent family,

the poverty rate would fall to 2%.

The real problem with the welfare system

is that it provides short-term incentives that are bad,

masking long-term outcomes which can destroy your life,

but they mask them pretty effectively.

Norberg: Monique has been on welfare all her life.

She watched as her mother died of AIDS,

and later, had her first child at age 16.

Monique: I was just trying to find love in all the wrong places

and bumped into my son's father.

I was expecting to have a family,

and he was just looking for somebody

to just lay around with.

Norberg: At the time, welfare seemed like a solution to her problems.

When I first got on welfare, I did.

I felt like I was getting into a Jacuzzi relaxed.

I was able to take care of my son.

But then you start...

Yeah, you sink.

Everybody sinks.

You're 16, 17 years old.

You're pregnant.

You are going to get a pretty --

a reasonable cash income,

from your point of view, at that age of life.

You're going to get, maybe, a free apartment.

You're going to get food stamps.

You're going to have healthcare for the baby.

All these things, all of them make it easier

to have that baby

and not necessarily say to the guy,

"Step up to the plate and take care of it."

Norberg: As single parenthood rises,

increasing rate of poverty in America,

the risks of single motherhood

and the importance of marriage become critical.

Sawhill: If you are your romantic partner are using condoms,

at the end of a five-year period,

your chances of getting pregnant are 63%.

The probability at the end of five years

that you're going to get pregnant using the pill is 38%.

Now, most people don't know that.

If you use a long-acting form of contraception,

and that means either an IUD or an implant,

then your chances of getting pregnant

are around 2% at the end of 5 years.

♪♪

Norberg: Today, Monique and her children live in public housing

on Staten Island in New York City.

Until recently, like so many others,

Monique was a single mother on welfare.

All that changed when she married Keith.

Monique: I got married because --

to live as God expect me to,

and I try to be honest with public assistance

and let them know that we live together,

and we're married.

And we thought that adding him onto the case

would benefit us,

but we lost out.

The short-term incentive

is you're probably better off if you don't get married --

terrible long-term incentive,

but a perfectly understandable short-term incentive.

I don't know.

It's hard to find a job nowadays.

Yeah, it is. How do you think

your West International interview went?

It went all right. It went all right?

Yeah.

I hope you get it too.

Monique: Keith used to get, like,

almost $300 in food stamps,

and I was getting almost $600 in food stamps.

Us together now,

we're getting, like, $400 and something

in food stamps.

It looked like it was better when I had my own case

and you had your own food stamps case... Yes.

It definitely looked better.

...because we had more money coming in.

More help.

The way the system is set up

is you're better off single than you are married

on public assistance.

Doar: Well, the welfare system discourages marriage

in a very simple way.

It combines the income of the two people in the household.

So when they're married,

both of their incomes count as eligibility factors

in determining whether they're going to get assistance.

So the more income they have from the combined sources,

the less benefits they're going to get.

That definitely sends a disincentive to marriage,

and that's a troubling fact.

♪♪

Norberg: Throughout history,

as nation after nation has become prosperous,

each has developed programs

designed to help its poorest citizens

at the state's expense.

As early as 1889,

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck of Germany

created an old-age pension for workers

who could no longer find employment.

Helping the poor, it seems,

has always been a government concern,

and it's likely to remain so.

Murray: The very beginning of the welfare system

was the passage of the Aid to Dependent Mothers

early in the New Deal.

And you know what?

It was perfectly reasonable.

What did they have in mind?

Frances Perkins was the secretary of labor

at that time,

and she had in mind widows,

widows with small children,

and they needed help.

What is a more natural object of our affection?

Norberg: When the stock market crashed in 1929,

the world entered the Great Depression.

After his election in 1932,

Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted federal reforms

to help the poor,

including cash assistance for single mothers.

With 20% unemployment in America,

massive public-works projects strengthened families

by providing employment in the difficult time.

[ Crowd chanting indistinctly ]

I pledge myself

to a New Deal for the American people!

Roads, public parks, dams and bridges were built,

tying work directly to assistance,

but even President Roosevelt realized

that there was a limit to what the government could do.

Doar: President Roosevelt certainly said often

that welfare was not intended to be for a lifetime

and not intended to replace work.

And to the extent that we've gotten away

from that sentiment in some of our programs,

that's unfortunate.

♪♪

Roosevelt: The lessons of history,

confirmed by the evidence immediately before me,

show conclusively

that continued dependence upon relief

induces a spiritual and moral disintegration

fundamentally destructive to the national fiber.

To dole out relief in this way

is to administer a narcotic,

a subtle destroyer of the human spirit.

We must preserve not only the bodies

of the unemployed from destitution

but also their self-respect,

their self-reliance,

and courage, and determination.

Murray: It all started out so innocently.

And if I'd been alive then,

I would've been in favor of it then,

but it ratcheted up very slowly.

Even by the end of the 1950s,

the welfare roles were small.

The amounts of money were small.

Welfare really was not, at that time,

an attractive way to try to live.

Norberg: Roosevelt remained true to his convictions

and phased out emergency public projects

as the economy improved.

From the 1940s to the 1960s,

poverty fell dramatically in the United States.

[ Applause ]

In 1964, the Great Society and War on Poverty programs

were inaugurated in the United States

from President Lyndon Johnson.

And this administration today, here and now,

declares unconditional war on poverty in America.

[ Applause ]

The ideas were great.

I mean, you listen to the early speeches,

and it was soaring rhetoric about the whole human person,

the dignity of people,

and not wanting people just to be on the dole...

Our aim is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty

but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.

[ Applause ]

...and great intentions.

But they weren't fulfilled.

The truth is that dependency grew and grew fast.

More and more families

were multigenerations in poverty

as a result of these programs.

[ Applause ]

Sawhill: Johnson's war on poverty

was an admirable attempt to deal with a problem

that had been kept in the shadows for too long.

We really thought that it was very simple.

And by "we," I mean, me too.

You have people who are unemployed?

Have a jobs program.

That'll take care of that.

You have schools in the inner cities

that are turning out kids

who don't know how to read and so forth?

Pay teachers more, and put more resources into the school.

You'll get better results.

Where we failed

is to make people more self-sufficient.

I don't think we've done a very good job there.

There are a whole bunch of things

that seemed like they would be easy to do.

And within half a dozen years, it was quite obvious,

they were really, really hard to do.

I mean, there was so much poverty.

How do you solve that?

And the answer was, according to many of those programs,

"You spread money around."

People don't have very much money

and so you give them more money

and then they'll be able to flourish.

They'll be able to thrive more.

Well, that's not right.

Norberg: Instead of ending poverty, progress slowed,

and then it stopped all together.

In 1996, President Bill Clinton

instituted work support and time constraints,

determined to get the train back on the tracks.

Man: So, Mr. President?

A long time ago, I concluded that the current welfare system

undermines the basic values

of work, responsibility, and family,

trapping generation after generation in dependency

and hurting the very people it was designed to help.

Today, we have an historic opportunity

to make welfare what it was meant to be --

a second chance, not a way of life.

Bill Clinton had the advantage

of a couple of decades of social science

that told him how hard it was

to do the things that L.B.J. had thought he could do easily.

Sawhill: It was a bipartisan effort,

but it was controversial to be sure.

Doar: It said very clearly

that there is a two-way street here

with public assistance.

If you want our assistance,

you need to do something

to show that you're being responsible

and moving toward the work place.

You didn't find a job. You get kicked off the rolls.

It's what we call "shift and shaft."

It shifts the problems to the state and local levels,

but most of all, it shafts poor people

and their children.

Murray: The opposition to it

was expressed by the left in just those terms,

that it was going to be Calcutta on the Hudson.

When we did interviews with mothers

who had been on welfare,

they said they wanted to work.

It wasn't a right or an entitlement.

That was extremely important,

and what was the best part about that act

was that people responded.

And sure enough, when we reformed welfare

and provided them with more childcare

and more wage subsidies when they went to work,

they went to work in droves.

[ Applause ]

Norberg: Applications for cash assistance plummeted to record lows.

But other programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit

were expanded

to help offset taxes for low-income Americans.

Sawhill: We replaced the welfare program

with several other programs.

Most importantly,

something called the earned income tax credit,

which is a wage subsidy

that you only get if you're working.

Norberg: Today, it is lauded on both sides of the aisle

for promoting work and, therefore, happiness.

Despite the success of the 1996 reforms

and the best intentions of Roosevelt, Johnson, and Clinton,

today's welfare programs remain

a labyrinth of individual agencies,

with budgets rising every year.

It has almost endless rules.

If you earn too much at your job,

you lose benefits.

If you save money in the bank, you lose benefits.

If you marry someone with income or savings,

you lose benefits.

In order to avoid penalties like that,

people improvise,

and that creates activity

in what is known as the underground economy.

♪♪

[ Indistinct conversations ]

You got my orange juice?

Angel: All right, so it's all right. Come on. Let's go.

Sometimes, I have to break the law

and cash food stamps,

not for drugs,

not for none of my habits,

but for my kids.

Doar: As the food stamp program has grown,

it's become more and more incapable

of monitoring the proper use of the benefit,

which is a voucher.

It's supposed to buy food,

hopefully healthy food.

And instead what's happened

is that people are using the EBT card to trade

in order to receive cash benefits

at a discounted rate.

Let's just say I've got $300 in food stamps.

I don't have no cash.

I'm going to keep $200 in food stamps,

go to the supermarket,

and I'm going to take $100 in food stamps

and turn it into cash, meaning --

this is what welfare don't understand --

out of every $10,

the store will take out $3 for themself

and give you the $7.

So add it up.

Out of $100 in food stamps, you get $70 in cash.

Well, of course it's understandable.

I'm a human being.

I understand people in need

who face difficulties and who make difficult choices.

What I want is a government program

that is interested

not just in providing a voucher for food,

but is interested in

helping that family grow and prosper

through their own earnings and their own labor.

And, unfortunately, the food-stamp program

is insufficiently interested in those things.

So I'll meet you at 2:20, all right?

Okay?

I love you, sweetie.

Nobody's watching.

I don't like learning those tricks.

I don't like knowing those things.

I don't.

Welfare doesn't have no opportunity.

School, training,

busting your behind to get a job,

that's more worth it,

instead of you being on welfare, which is easy,

but be stuck on it for years.

You don't want to bring kids into the world

and be struggling.

Who wants to be struggling with kids?

What do you do?

Keep on striving...

I don't know.

...and make a better life for the kids, right?

Norberg: A few years ago,

unemployed and living in the Bronx,

Monique failed to pay her electric bill.

Her power was cut off,

and she turned to the only resource available --

the underground economy.

Let's go. It's time to go.

Monique: Our lights were out.

I had two little kids.

I remember my lights went out when I was a kid.

I was left in the house by myself in the dark,

and I refuse to have my kids living in the dark.

I had 12 hours to get that bill paid,

for them to come out and turn my lights on.

I did what I had to do as a woman,

as a mother, as a provider.

So I came up with a quick hustle,

found some drugs in my building,

and wound up --

About two or three weeks later, I got arrested.

The officers were shocked.

They did my fingerprints,

found out that that was my first-time offense.

I never did it again.

I wouldn't.

I'd rather come home with a paycheck,

even if I've got to wait a whole week and do it.

I would rather come home with a paycheck.

Norberg: Welfare policies have created negative consequences.

One example is the way

in which the poor are penalized

for good behaviors, like saving money.

Recipients have to spend down savings

and dispense with assets

in order to get help from the government.

Your Social Security number goes through a machine.

So let's just say

I wind up throwing $2,000 or $3,000 in the bank.

That'll ring up, and welfare will know that,

and, right away, within two to three weeks,

you'll get a letter stating

that they're going to cut you off of welfare.

If you don't want to get cut off,

you take that money out, spend it on whatever,

and welfare will say,

"Show us receipts. Bring your receipts."

We've set up, in our country,

a situation where too many workers

are thinking about multiple ways

to avoid working on the books

because they either don't want to pay taxes,

or they don't want to lose welfare benefits.

Both of those problems, we need to address.

Norberg: But for people like Angel

who can't put their savings in banks,

there is always the underground economy.

The University of Wisconsin has estimated

that as much as $2 trillion

may go unreported every year in the underground economy.

Some of those activities are illegal,

but a lot of the underground activities

are simply extralegal, even entrepreneurial.

For example, bartering --

exchanging services like car rides and babysitting

for food and cleaning services.

It may be that the underground economy

creates space for opportunities that would otherwise not exist.

♪♪

I'm Paris.

I love sneakers.

My name is Raudi.

I'm actually out here camping out, as you can see,

for the new Jordans coming out tomorrow.

I do it mostly to collect.

I've been collecting sneakers my whole life.

I had, until some point, almost 200 pairs of sneakers.

♪♪

Paris: It's a sneaker culture.

Like, we're all a part of it.

Raudi: Every weekend,

there's a new sneaker that comes out.

So we try to get as many as we can.

If I sell them,

I'll probably get enough to buy a house or something.

They go up in value within the year,

especially if they're brand new.

Raudi: We do this, basically, for a living.

I've been doing this for almost six years now.

♪♪

Norberg: Stores like Flight Club, Sneaker Pawn

and conventions like Sneaker Con

provide opportunities to buy, sell, and trade

second-hand sneakers.

Chase Reed of Sneaker Pawn

is well-acquainted with a new booming business.

Reed: So basically, we're a sneaker bank.

People can come to us and get money

instead of having to go to a bank

or having to go through somebody else.

Norberg: Because of the possible penalties

that come with a traditional bank account,

sneakers have become an inventive way to save.

Reed: Buying sneakers is not throwing money away

because it's an asset, just like everything,

just like a house would be.

Anything you own is an asset.

Same way you trade baseball cards,

same way you buy baseball cards.

you sell them.

Same thing with sneakers.

Man: If you're up to do the swap,

I'll do the swap but -- For which ones?

I don't know.

I got those already.

If you get 10 sneakers a week for $200,

and you sell them for $300,

and you do that for 40 releases, you get $40,000,

and that's just off of 10 sneakers.

So imagine if you get 20, that'll be $80,000.

If you get 30 sneakers, that'll be $120,000 and so on.

That's not including the sneakers that go for $2,000.

That's only sneakers that cost $300.

Thanks a lot, man. All right.

Appreciate it. All right?

I think anybody in poverty,

there's a million ways to get out

instead of going and selling drugs.

And sneakers are a big way to get out.

All right? I love you, Chase. I'll see you later.

Definitely. Holla.

All right.

Probably be back in a couple days, bro.

♪♪

Norberg: Most agree the best solution to welfare is a job.

But instead, poverty programs have spun out of control

and have proven difficult to run effectively.

One program in New York City

could potentially serve as an example for reform.

It's a simple, successful model

for transitioning the poor into work in the private sector.

For these men, work matters,

and it's not just about a paycheck.

Collectively walking 160 miles every day

in rain, sleet, snow, and heat,

they clear nearly 10,000 tons of garbage

from New York City streets each year.

It's the first job they've had in a long time,

and it's part of a training program.

But for them, this dirty work

is far more than cleaning streets.

A bucket and broom have become the first step

on a path to a new life

in an organization called Ready, Willing & Able.

Its Co-Founder is Harriet McDonald.

Our motto is "Work works,"

and what we give people and believe in

is a hand-up, not a hand-out.

Everybody gives up entitlements

as soon as they get here.

This is about earning your way to success.

Norberg: Ready, Willing & Able is a 10-month program

that begins with one month cleaning New York City streets

and culminates with a career in the private sector.

How is everything? Everything is great.

How long are you here now?

Norberg: It is specifically designed

to transition men out of poverty,

homelessness, and incarceration.

Thank you.

The program had an unlikely beginning.

McDonald: I was actually a screenwriter living in Beverly Hills,

and I was hired to write a screenplay

about a homeless little girl

who actually was a real person.

And I'm entering Grand Central

which, at that time,

there were thousands of homeless people living there,

and off this bench pops this little girl,

and that's April.

And she knew all the homeless people

because she had lived there so long,

and she was only 17.

And she had the quality

of a wild bird in this great station.

Norberg: Harriet became immersed in April's world,

and the two formed a strong bond.

McDonald: And I thought, "Well, I'll go home.

I'll write this screenplay.

It will save her."

And about a week after I finished the first draft,

I got a call that she'd killed herself.

Norberg: Fueled by April's death,

Harriet returned to New York

where she married homeless advocate George McDonald.

In 1985, they founded Ready, Willing & Able.

McDonald: At that time, everyone said,

"They're too lazy. They're too crazy.

They don't want to work" and all that stuff.

Norberg: Ready, Willing & Able's first contract

was to provide basic maintenance

for New York City's homeless housing.

From the first day, they outproduced the contract.

That was their level of motivation,

and we knew, then, that we had it right.

And since we've begun,

we've generated $750 million in revenue,

putting $250 million

into the pockets of the people

who work so hard in our program,

and our budget is $50 million a year right now,

and we're growing.

Norberg: Richard Norat was born into poverty

and introduced to drugs at the age of 8.

Richard: Good morning.

I had slept in cars.

I had slept in trains, rooftops.

[ Sighs ]

I've eaten from garbage.

I wanted to die sometimes.

I mean, I would wake up in the mornings,

and I was so dirty and smelly.

I'd get on a train or a bus,

and people would look at me in disgust.

And it would hurt because I could see them looking at me.

I didn't even have to look at them,

and I could feel them looking at me,

and I wanted to explain to them,

"I'm going through something right now.

This isn't me," you know, "Understand."

Norberg: Richard was serving a 20-year prison sentence

when he found out about Ready, Willing & Able.

When he was paroled,

they were his first and only option.

When I got here, they accepted me.

It was cathartic.

A weight was lifted off my shoulders.

I got to eat.

I got to shower.

I slept in a great bed.

The energy was so positive.

Everybody's building.

Everybody's calling me "sir."

Nobody calls me "sir."

So how long have you been with us now?

19 months now.

I remember you saying to me once that,

"Do all you can while you're here

because by the time you look,

it'll all be over."

Yeah.

I mean, sometimes

when you're re-creating or reinventing yourself,

it looks so far away.

But then when you get involved in the actual work of it,

it goes quickly.

Well, I worked with Ready, Willing & Able

when I was the commissioner of social services

in New York City,

and the program is a success

because it treats people as individuals

who have capabilities and have assets

and can go to work and want to go to work.

Remember this about our program.

Once, The more that you come here,

you still have to do the work. Yes.

You got up every morning.

You worked hard every day.

You stayed drug-free.

You went to class at night.

You did everything necessary to re-create yourself.

That's what makes us different.

It's fantastic. You know?

That's real.

McDonald: The most important thing we can give people

is economic opportunity.

They will do the rest, I promise.

These are guys that nobody wants to deal with at all,

and, yet, these are the people that are involved

in the Ready, Willing & Able program.

They have astronomically high rates of success

in the job market,

low rates of reincarceration,

and high rates of flourishing and happiness.

I was talking to a guy in New York

who had been in prison for a long time.

He was working for an exterminator company.

It was the first real job he'd had,

and I asked him, "Are you happy?"

And he said, "Let me show you something."

He said, "Look at this e-mail. It's from my boss."

And the e-mail said,

"Emergency bed bug job, East 65th Street.

I need you now."

"That's the first time in my life

anybody has ever said those words to me."

That came through work.

Richard: I never thought I could ever associate

my name or my life with a career.

Doctors have careers. Lawyers have careers.

I'm licensed in the State of New York.

Look at that sight.

That's a beautiful view.

I'm free. I'm literally free.

♪♪

Here! Look right here. The e-mail's in there.

Look for it. Look for it.

-It says it, right? -Yeah.

Steffani: It says, "Your background check has cleared,

and we're excited to offer you a position."

Norberg: The value and joy of work

is part of our shared humanity.

When persistence meets opportunity,

it can lead to redemption.

Angel: I got a job working for munchery.com.

It's delivering, like, high-class food.

This job really changed me.

I love this job.

It's the best thing that's ever happened to me.

Steve, come get your coat.

Kayla, come get your coat.

Yeah. Grab you bookbag.

Okay. Who first today?

-Me! -Me!

-Steve. -I'm second.

Monique: For me to earn my own success

is a big deal.

The training I have coming up is a home health aide training.

It's the opportunity of a lifetime.

That's how I look at it.

Norberg: Monique cannot wait

to start work as a home health aide.

When I put on my uniform...

[ Laughs ]

...I'm getting up at 5:00 in the morning.

[ Laughs ]

I'm going to be fully dressed. I'm going to be ready.

I've been waiting for this opportunity

for a long time.

Oh, you did it.

[ Laughs ] You did it.

All right. Go to your speak button.

Let's see how it sounds.

Norberg: But for Chris, things changed tragically.

Just months after filming,

her courageous daughter, Madrona, passed away suddenly.

Moving forward

with Madrona's spirit of facing challenges,

Chris made new plans.

She has relocated to a nearby city

to find work and a better future for her girls.

We have learned there's hope in seemingly hopeless cases.

To ensure more people have the best chance at happiness,

we need to re-evaluate our policies and perspectives.

Brooks: The whole idea of, "Send us your huddled masses"

engraved on the Statue of Liberty,

they didn't say, "Send us your huddled masses,

and we're going to park them in public housing

and give them food stamps

and make sure that they're out of sight to everybody."

No.

The problem that we have

is not just the misdesign of programs.

It's not that we're spending too much.

It's that we have the wrong philosophy.

Poor people are not liabilities to manage.

They're assets to develop.

Doar: But when we're talking about people

who are really struggling and facing difficult times.

the objective is not to save more money.

The objective is to help more people

in the most effective way.

We need to rethink the welfare system,

not on the basis of how much cash is going to whom,

but on the basis of how we can bring earned success

and thus greater flourishing and happiness

and better true welfare

to the people who need it the most.

Norberg: Like so many prosperous countries,

Americans build a huge and well-meaning bureaucracy

to care for its poor and unfortunate.

In theory, the government can give you anything

except that one thing that gives you self-worth

and the respect of others --

knowing that you made this happen,

that you accomplished this yourself.

Until we revise the system,

something essential remains missing --

the independence and happiness

that comes from earned success from work.

That is the human cost of welfare.

♪♪

♪♪

♪♪