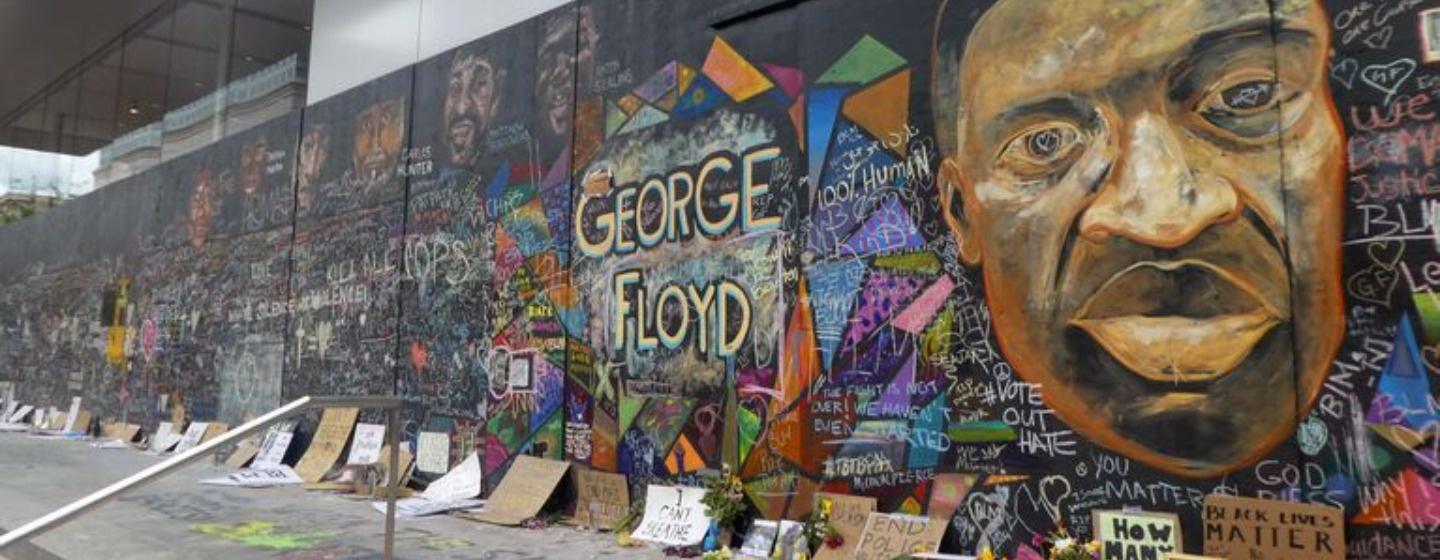

The city of Portland, Oregon, has a long history of protests. But 2020 was unparalleled, as people took to the streets for months to stand up against racial injustice and police brutality following the killing of George Floyd.

Floyd’s death, which occurred last spring after a police officer knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes, sparked outrage across the country.

In Portland, protests started in late May and continued into the fall. On some days there were crowds upwards of 10,000 people. The demonstrations were largely peaceful, but at night there were reports of looting and violent clashes with police. Saying the situation in Portland “was out of control,” President Trump sent federal law enforcement officers, whose aggressive tactics made national headlines.

Coverage of this extraordinary story by PBS member station Oregon Public Broadcasting serves as a good example of how stations can fairly and accurately report on major breaking news in their area.

“When the federal government sends in hundreds of armed troops into a city like Portland, I think our job as journalists is to ask the tough questions of why that’s happening and what that reasoning is,” OPB news editor Ryan Haas said. “We give everyone a fair chance to respond, but we ask the tough questions on behalf of the public. I think that’s our job, particularly as public media.”

Fairness and covering “both sides”

One of the core principles of the PBS Editorial Standards is fairness. Fairness requires that information be presented in a “respectful and responsible manner.” But it does not require that all conflicting viewpoints be given equal time.

Just a few weeks after the protests started, OPB’s CEO and president, Steve Bass, issued a statement stressing OPB’s commitment to anti-racism and the First Amendment.

“Many of the issues we examine have at least two sides. But we must take a clear stand on certain issues,” Bass wrote. “Racism doesn't have two sides. It’s a scourge. We have no obligation to balance anti-racism with racist perspectives.”

Those sentiments served as the newsroom’s guiding principles during its coverage, OPB news director Anna Griffin said.

“I think you can present all viewpoints but also be critical of folks who are in power, and have a lot of power, and what motivations they may have to present a particular story that maybe is not in line with what on-the-ground reporting shows,” Haas said.

Becoming a part of the story

As aggression from law enforcement escalated, journalists were among those caught up in the violence.

The PBS Editorial Standards explain that journalists “should endeavor to minimize, and to the extent possible, eliminate” any interference with events. In this case, however, journalists were aggressively confronted—and in some cases injured— by police, raising important constitutional questions about press freedom.

“In the case of the protests this summer, police were treating journalists as if the First Amendment did not exist. And that’s something that we’re going to be on the record about,” Griffin said.

OPB posted an article, “Police Keep Injuring Journalists Covering Portland Protests,” about two local reporters who had been hurt by police despite identifying themselves as press. One journalist said she was hit from behind with a baton, and another journalist said he was shoved into a wall.

“It was a case study in what we were seeing—the indiscriminate use of violent tactics by law enforcement against just about anybody who was out there,” Griffin said.

Thoughtfully using language

Accurately reporting on the chaotic situation required journalists to use language with great care.

As part of the core principle of accuracy, the PBS Editorial Standards state that producers must “be mindful of the language used to frame the facts to avoid deceiving or misleading the audience or encouraging false inferences.”

Because of OPB’s history of covering extremist movements, Griffin explained, the station has a newsroom culture “in which people feel comfortable and proactively have conversations about the kind of language that we use to describe people.” The station also has a language advisory group that meets regularly.

In an article in mid-July, OPB contextualized the use of the word “criminal” to describe the protestors: When Portland Deputy Chief Chris Davis characterized the protesters as “criminals who had co-opted a peaceful movement,” OPB explained that such language was “a tried and true tactic used by government officials over the decades to delegitimize social movements.”

A later article explained what constitutes a “riot” or an “unlawful assembly” and the vague laws used by police to make those declarations.

Providing sufficient context

Along with covering breaking news, OPB took the time to step back and put events into context—another important component of the principle of accuracy.

The PBS Editorial Standards state: “Accuracy includes more than simply verifying whether information is correct; facts must be placed in sufficient context based on the nature of the piece to ensure that the public is not misled.”

Stories that contextualize fast-developing events are perhaps the most important to provide the audience.

“It’s really easy in a breaking news situation to get so caught up in what you’re seeing and experiencing in the moment that you forget that the audience is not tracking it as nonstop or as rapidly as journalists,” Griffin said. “A lot of what we can do in public media better than anybody else is providing that kind of context and that kind of background.”

Haas said there were regular discussions in editorial meetings about the kinds of stories that deserve further explanation.

One OPB article, “50 days of protest in Portland. A violent police response. This is how we got here,” gave readers a detailed timeline about what happened when federal law enforcement officers began showing up at the protests.

Local stations need to think about their audience, Griffin said. No matter the size of the station or the scope of the story, stations should ask what information the audience wants, expects, and needs to understand what is happening.

Contact Standards & Practices at standards@pbs.org