Lilit Lesser, Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light | MASTERPIECE Studio

Released April 7, 2025 34:19

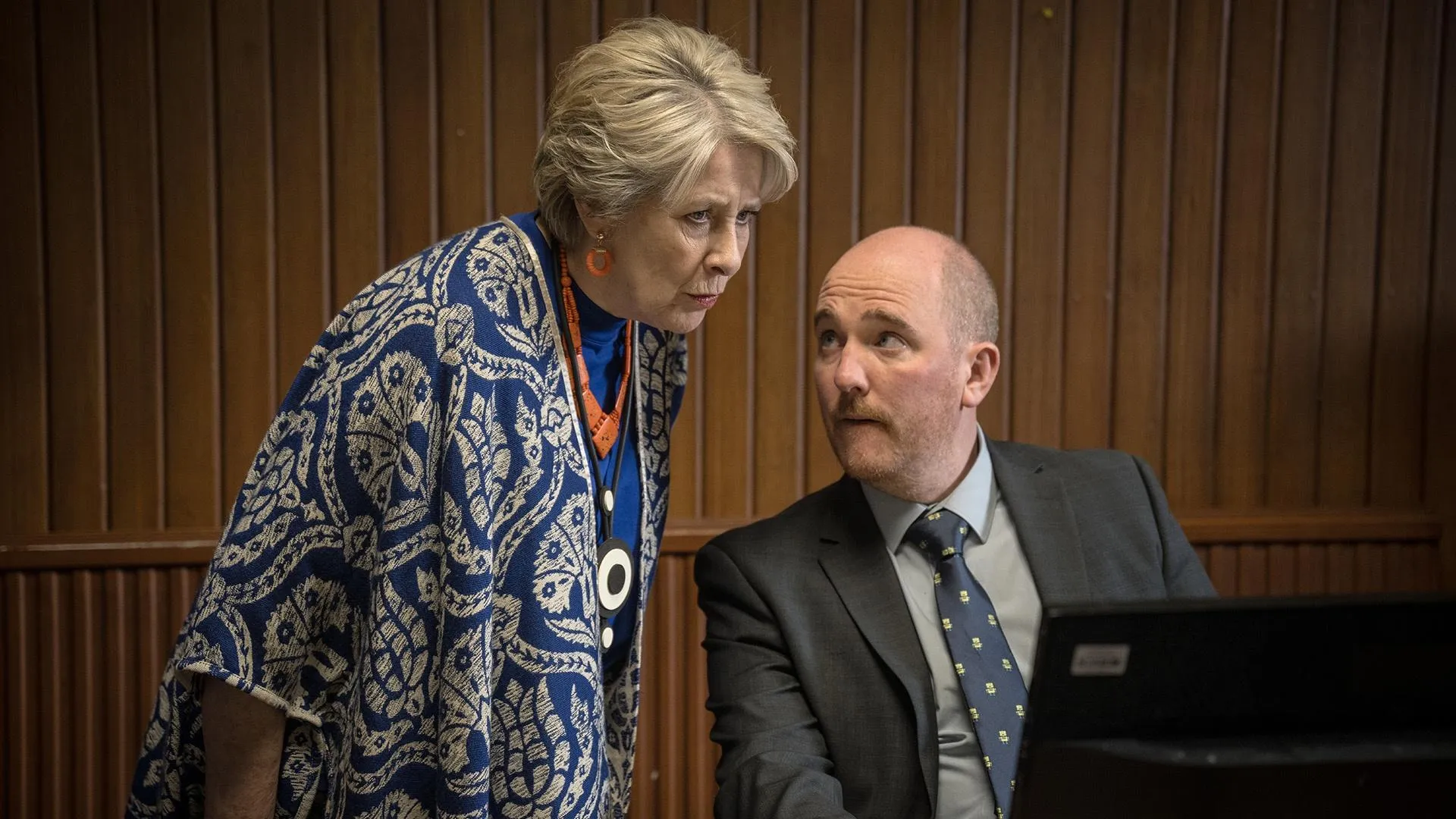

WARNING: This episode contains spoilers for Episode Three of Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light.Actor Lilit Lesser is a familiar face to MASTERPIECE audiences, appearing in both Wolf Hall and Endeavour. Lilit joins us today to discuss playing Lady Mary in Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light, and examine how the character balances faith with fortitude.

This script has been lightly edited for clarity.

Jace Lacob: I’m Jace Lacob and you’re listening to MASTERPIECE Studio.

Mary Tudor is remembered as the first female monarch of England. But her path to the throne was far from guaranteed.

When Mary was 17, her father King Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church to divorce her mother, Katherine of Aragon, after 24 years of marriage, and declared himself the Supreme Head of the Church in England. Mary lost her title of Princess and became illegitimate. And as if that weren’t enough, Henry also demanded his daughter abandon her Catholic faith and acknowledge Henry as the head of the church. But Mary would do no such thing.

At the start of Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light, Mary is in exile, her mother dead, and her father resolute. Unbeknownst to Mary, Thomas Cromwell made a promise to her mother Katherine to keep Mary safe. In an effort to do so, Cromwell persuades Mary to sign the oath. And now, he wants to present her with a ring inscribed with a special message.

CLIP

Cromwell: I wanted to ask your majesty’s permission that I might give this to the Lady Mary.

King Henry: “In praise of obedience”. Very apt. And do you think my daughter will take the point?

Meanwhile, since meeting with Wolsey’s daughter Dorothea in Episode Two, Cromwell has been plagued by thoughts of betrayal. His conscience runs wild. But something even larger is brewing outside the castle walls. Cromwell hears word that a rebel army is approaching. They believe the king is dead, Cromwell rules, and that he wants the king’s daughter for himself. Cromwell fears for Mary’s life and petitions Henry’s latest queen, Jane Seymour, to bring Mary out of exile and into the kingdom.

CLIP

Jane Seymour: My lord Privy Seal. Chancellor of Augmentations.

Cromwell: Your Highness. Why not ask the king to fetch Lady Mary here?

Cromwell is successful in bringing Lady Mary to court, but her unexpected presence raises certain suspicions.

CLIP

FitzWilliam: The almanac said this would be a great year for surprises. And here’s the Lady Mary back at court long before she was looked for. This is your work, Crumb.

Cromwell: But you’re mistaken, Fitz, as you’ll remember it was the queen who requested Lady Mary’s presence.

Today, actor Lilit Lesser examines how their character, the pious Lady Mary, balances faith with fortitude.

Jace Lacob: And this week we are joined by Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light star, Lilit Lesser. Welcome.

Lilit Lesser: Thank you.

Jace Lacob: I want to go back in time a bit to when you're 17. Wolf Hall is your first acting credit, and what a first credit for an actor to have. How would you describe the experience of working on Wolf Hall as a first time actor and how much of an impression did it leave on you?

Lilit Lesser: Gosh, I mean, even just you bringing up, I'm right back there. It was this kind of ridiculously sunny, beautiful day in the English countryside. It was a golden day. It just felt like a dream come true. And to be doing this tiny little scene that's just a moment, that was alongside such extraordinary actors as Mark Rylance and the amazing Joanne Whalley, I just remember being in utter awe of the two of them, and of Peter. I think it says a lot about Peter as a director and as a person that I feel that there was no change in the amount of respect and kindness and just collaboration that I felt between us, even as that kid compared to now. Peter is just so full of respect and he's so brilliant and so open to collaborating with his actors.

I just remember Mark being so kind to me as well because, I remember him leaning over very kindly just before we were about to start and saying, do you know what happens now? And me sort of wide eyed, shaking my head like, no, I have no idea what's going on. And him just taking the time to explain things to me, which was so kind of him. I remember him making me laugh because there I was incredibly serious trying to do the best job possible, and still, because I'd never been on a set before, I wasn't entirely sure when we were filming and when not. Yeah, gosh, just, just extraordinary to be in the presence of such fine actors for my first ever job.

And of course also to work with my dad. We were auditioning, going up for things at the same time. He was, I think, being seen for a couple of roles in it, and eventually, of course, ended up being incredible as [Thomas] More. And we, of course, didn't have any scenes together, but I remember being delighted that I could watch him that day in a scene where he was torturing Jonathan Aris, the fine actor. And just having great fun and then him coming to watch me. That felt so warm. What a delight.

Jace Lacob: That's amazing. I love that. The Mary we meet in Episode One is a different woman than the young princess we saw in Wolf Hall. What do you make of the character of Mary Tudor as we pick back up with her at the start of The Mirror in the Light?

Lilit Lesser: Yes. Well, we find her in these dire straits. She's railing against this impossible decision that she has to make. And it's such a journey because it's really quite fascinating from her childhood, the contrast between how she was treated as a child, there was almost this quality of, a kind of mythical quality and a reverence around her being the only one of her siblings to survive.

And she was treated in quite an unusual way in terms of gender roles. In some ways it was incredibly conformist and sexist and there was always this idea that no matter how educated she would get, she would always ultimately be a property and a pawn and to serve as a wife, and for political alliances in that way. But at the same time, she was so highly educated, to the degree that very few women were, especially at the behest of her mother, Katherine of Aragon, who was also incredibly intelligent and insisted on this incredible humanistic education for Mary.

But she was doted on, she was loved, and she was, all in all, a very happy child. And then, to have all of that taken away so brutally when things shifted. And her mother, who she was incredibly close to. In the years before we see her in the new series, her mother has died and she's been separated from her. She wasn't even allowed to be with her mother as she was dying, and then to be very deliberately isolated by her father from everything that made her feel secure and happy.

So yeah, she's in a very dire place, but she's also in a place of extreme disobedience. Some would call it incredibly brave. Henry called her the most obstinate creature he'd ever met, which I think is rather rich coming from Henry. But yeah, incredibly dangerous to be in this position of refusing to acknowledge him as the head of the church, because that is what she's being asked to do. She's being asked to basically renounce her mother, her faith, and her title, all of these things that are at the core of who she is. So yeah, that's where we find her in this absolute tightrope walk of defiance and danger and grief and pain. So that was an incredibly powerful place to be, on that cliff edge.

Jace Lacob: “When is she not ill?” Henry says of his daughter in Episode One. Though previously the king boasted about how Mary never cried as a baby. How do you see illness informing her character?

Lilit Lesser: Oh, wow, hugely. Yeah, it was said that she died of, people think it could be ovarian cancer. She certainly had incredibly painful gynecological issues through her life. Some say that she might have had something like what we know to be endometriosis, which was really resonant, actually, because I personally have endometriosis. And it's incredibly common, but very under researched and affects so many, including Hilary Mantel, who…

Jace Lacob: She wrote about it in her memoir, Giving Up the Ghost, in fact.

Lilit Lesser: Yes, yes. So yeah, I think it plays a huge part, and it's beautiful. I'm sure that her own experiences informed her, the kind of huge empathy and detail and just the huge humanity that Hilary Mantel gives all of these characters in this world. These are not historical figures, these are people who ache and are in pain and you can feel the very visceral, very daily reality of what their life was like. That's some of the power of it. And that was certainly, as an actor, something I was hugely aware of, even just the physical pain of wearing those costumes, the corsets and the way they drag your shoulders down, you can feel the oppression, you can feel the closeted-ness in just the clothes you're wearing.

Jace Lacob: Mary's refusal to acknowledge Henry as the Supreme Head of the Church of England, is in keeping with her devout faith as a Catholic. But Mary also wants to be restored as Henry's heir. How does she reconcile those two tracks? Which do you see as being more significant to her, the throne or her faith?

Lilit Lesser: Gosh, that's such an interesting question, and one that I think Mary is pushed to the edge in trying to reconcile. There's this question of how important it was that it was Cromwell that had to come to Mary and that they sort of found this way through it. She wasn't required to write the words herself or to sign the official letter from Henry. And she would use this phrase, I think, “…as far as my conscience and my God allows.” which I think shows incredible spiritual and intellectual gymnastics and political acumen. It gives a glance into her inner struggle and we can see how devout her faith was to the extreme.

But we can also see what political acuity she had and that she understood how her father worked and understood very well the ways in which she had to play the game to stay alive. And I think she did know what she was doing. Oh gosh, yeah, that's such a fascinating question. I wish I knew, I wish I could have read her mind.

Jace Lacob: She was able to sort of contort herself into that pretzel and make it work with all of those things going on inside of her competing for attention. After her disastrous meeting with Norfolk, Mary receives Cromwell as a visitor, coming face to face with him for the first time since their meeting with Katherine.

CLIP

Mary: I hear you are Lord Privy Seal. You are grown very grand, Lord Cromwell. I suspect you were always very grand, only we did not see it. Who knows God’s plan?

Cromwell: I understand Mr. Chapuys has spoken to you.

Mary: Yes. Eustace offered me certain advice.

Cromwell: Which disappointed you?

Mary: Which surprised me.

Cromwell: I hope he brought home to you the peril in which you stand.

Mary: He said Cromwell has used all the grace that is in him, risked all. He said you feel the axe’s edge.

Jace Lacob: What does Mary make of Cromwell here? Does she innately trust him?

Lilit Lesser: This relationship between Mary and Cromwell has just been so fascinating to me from the beginning, because here you have two people who are polar opposites in their politics, and yet, within this script and throughout the series, there's this draw between them and this understanding. And it's very ambiguous and just so rich. And also you have the added layer that this was the man who orchestrated the demise of her mother who carried that out.

And you know that's so encapsulated in that scene from the first season where he is delivering the worst possible news to them, and yet still offers this very humane act of kindness in offering her a seat and basically saying to this child, who I think is used to people underestimating and belittling her, I see your pain, I see you. I think they are both very adept at kind of seeing deeply into situations and playing the game. And doing this, it was interesting to find out that Mary's very fond of gambling. And we see that Cromwell too is a gambler.

Jace Lacob: They're both sort of the ultimate chancers, the two of them.

Lilit Lesser: Aren't they? And they both just have incredible chutzpah and I think they respect that about one another.

Jace Lacob: Mary admits to feeling alone. No one has spoken for her. She's essentially a prisoner at Hunsdon House in this sort of shabby privy chamber. Cromwell comes with the letter. He tells her not to read it so she can repudiate it later.

CLIP

Comwell: You have put all your strength into saying no, now you must say yes. Do you think only weak people obey the law because it terrifies them? Do you imagine only weak people do their duty because they dare not do other? The truth is far different, Mary. In obedience, there is strength and tranquility and you will feel them. It will be like the sun after a long winter. Choose to live and you will thrive. Don’t read it, then you can repudiate it later if you have to.

Jace Lacob: This oath goes against everything she believes. One that makes her claim to the throne illegitimate, despoils her mother's reputation, and goes against her very faith in God. What does it take for her to sign it knowing all of that? Does she believe, as Cromwell says, that signing it will be like the sun after a long winter?

Lilit Lesser: It's such a rich scene. There are so many moments where I wonder if one tiny thing had gone slightly differently, would we end up somewhere totally different at the end of the scene? The moment where Mary accidentally shatters the glass jug, if she hadn't done that, what would she have done?

She's on such a razor's edge in that scene and it's so immediate and so in the moment, nothing has been decided. Everything is falling into place at kind of extraordinary speed in the moment. And that's why it was so electrifying to read and to play, and to be there and feel that this really could go any way, and yet her entire life is at stake. And hearing Cromwell say every single thing that he says, and at the same time, there is a huge part of her that I think is desperate to hear these words and has needed to hear them in exactly this way. And that she knows that Cromwell knows that she needs to hear them in exactly this way.

That she will not respond to being told how much danger she is in, being condescended to, being forced, that she needs to be given this level of agency and flexibility to do this pretzel contortion to make it possible. So many delicate tiny parts of this, it’s like this intricate little watch that could explode any second. And Cromwell is placing the pieces with such precision.

And there's this recognition between them, I think, in the moment of him doing that, if that makes sense. And she sticks to her guns. She chooses to be a martyr, and martyrdom was incredibly fashionable at the time. There is so little in between her and the abyss. And then there is also a huge part of her, like in all of us, that fights to live. And yeah, I just think it's such masterful writing to capture all of that in the scene.

Jace Lacob: You mentioned precision with Cromwell earlier, but there's also in this scene I think a gentleness that reminds me of their encounter in Wolf Hall when he visited Mary and Katherine. He gets a chair for Mary. Here he moves the table, he hands Mary the pen. Did you and Mark look to mirror that earlier scene in Wolf Hall?

Lilit Lesser: I don't know, I don't know how conscious it was. It could well have been very conscious on Mark's part. To me it felt kind of more responsive to what was alive then and there because when I look back at it, I look back very fondly because I feel like I was excellent casting for Mary in that I, myself, was incredibly clumsy. This came up a lot during the shoot, gosh, I was trying so hard not to smash that very smashable jug before I was supposed to.

There's this lovely moment, I think, where Mark says, “I'm just concerned that she doesn't trip over and land in a heap at Henry's feet.” And yeah, let's just say that was, that was very good casting. And so I always smile when I look at that moment. I think you mentioned just now of Mark moving the table. I think that was because I would continually, throughout the shoot, underestimate how long my bottom was. Because you have these big bustles, that's not what they were called of that era, but the bum pads. And so I would be constantly underestimating the length of my derriere and that was one such moment where I just quite confidently stood up from the table and moved away. Mark sort of made a course for my bottom to emerge. So more than anything else, it was practical, I think, but I think that in itself is what's so lovely about it.

MIDROLL

Jace Lacob: So there is this intimacy between Mary and Cromwell. There is the warmness of the letters between them. There are rumors Cromwell intends to wed Lady Mary, rumors that he shoots down when Chapuys brings them to his door. And in Episode Three, we come to my favorite scene when Lady Mary summons Cromwell to her bedchamber at night. And she's wearing the ring that Cromwell had commissioned for her with its oath of obedience. And she knows that while Henry gave it to her, it originated with Cromwell.

CLIP

Mary: You see? I am wearing your verses. “In praise of obedience”. Though my father gave them me, I know their origin.

Jace Lacob: And there is this tension between the two of them, an oddness, but also this physical closeness. How did you look to play the uncomfortability in this scene with Mark? What is unspoken here?

Lilit Lesser: Yeah, God, there's just so many layers that it could be. And it's extraordinary and preposterous that there should be this intimacy and that they should be drawn to one another. But I think they are in this telling, it feels that they are, and that they both know it to be unimaginable and absurd. And these are the layers, I think, I can't remember exactly, it was like Peter saying, do you think she's warning him off, as I think Cromwell interprets it, because it feels like it's going so into dangerous terrain and then Mary suddenly describes him as being like a father.

CLIP

Mary: Do not make light of what you have done for me. You saved me when I was drowning in folly, when I was almost past recovery. Your care of me has been so tender, like that of a father.

Lilit Lesser: It just feels so loaded, that moment.

Jace Lacob: It's such a, you used the word tightrope earlier, but it is such a tightrope scene. And it almost plays like a declaration for a split second that you think she is going to say something that can't be unsaid, but then she pulls it back. So I am curious, how did you look to live in that very thin, narrow, tightrope space from which you could have fallen either side?

Lilit Lesser: It is such a tightrope, and I think something I really enjoyed about Mary is that there's a candor to her. She's so adept at putting on masks as we've seen when she's in with her father. She sort of has a mask she wears as ruler, as a ruler to be, as a politician, as a faithful obedient daughter. And then there's almost a defiance in the way when she's with Cromwell, it's almost like a dare to him there's something provocative in it, in just the kind of purest sense of that word, or maybe not, in that it feels like she very consciously removes her mask and kind of brazenly shows him all her cards. As if to say, what are you going to do now?

But then, being who she is, having the power she has, she's also able to just snatch those cards back at any time. It's filled with these moments that feel like she's almost wielding her candor and her brazenness as a weapon. But, that in itself, almost at the same time, paradoxically, feels like the truest, almost most vulnerable revelation that she could be giving to somebody. And, how intimate, I think, if that makes sense. And there's a brazen intimacy about her and a chutzpah that comes across in unmasking herself, and then as quickly as she has, snatching it all away again. And yeah, that feels like it's happening in that scene.

Jace Lacob: We are at this point sort of halfway through The Mirror and the Light. What lies ahead for Mary in the final three episodes?

Lilit Lesser: From this place of fragility and this precipice, she quite quickly finds her footing again, and I think no sooner has she done that, her sights are quite firmly on her future, and it feels like nothing will come in the way of that for her. It's almost as if she's tapping into this prophetic quality that she mentions in that first scene of, I was the only one of my siblings to survive and it must be that God has great plans for me. It feels like she's on a trajectory towards her future as a ruler.

She can't foresee what's to come, but I think she is ambitious, and I think she, at the very least, is determined to survive and thrive in the still fragile but more secure place she now has at court. And there's something very poignant about, as intense as the relating between Cromwell and Mary has been in the first episodes, how intense and intimate, there is a clear withdrawal that happens as it goes on. There's something that, you know, Mary seems to almost close something off and steer herself in another direction. Again, there's many possible readings of this. And does she sort of leave Cromwell in the dust, in a way?

Does she know that it's now too dangerous to align herself with him? Does she sort of sacrifice him in a way, him having saved her life? That feels very, very raw and sad for me to think of. Yeah, I think she does kind of leave him in the dust in a way.

Jace Lacob: You have the distinction of being the first guest on this podcast whose parent was previously a guest on the podcast. Your father, Anton, was a guest back in 2016 for Endeavour, where you played Ravenna Mackenzie. Did growing up with an actor father color your desire to pursue acting professionally?

Lilit Lesser: Hmm. Not when I was very, very little. I actually wanted to be, well, first I wanted to be a giraffe keeper in a zoo. Then I wanted to be a doctor, like my wonderful grandma was. But then, yeah, very quickly I did. I just fell in love with it and I was lucky enough to have totally grown up in that world. I would, as a baby, be kind of napping in my dad's dressing room while he was on stage at the RSC and yeah, it was magical.

What a magical privilege to see your dad be a thousand different people and not just be that, but do that with just the immense talent and grace and sensitivity and intelligence that my wonderful dad has. And he's always very much kind of encouraged me to follow my own path and not really, yeah. I remember, I think when I got my first acting job, he was like, great, remember to take the bins out. And I just think that's wonderful. That's just, yeah.

Jace Lacob: It's a very dad thing to say.

Lilit Lesser: It's a very dad thing to say. It's the important stuff of life, isn't it?

Jace Lacob: You've acted in film and television with roles on Endeavor and The Queen's Gambit and Moonhaven, among many others. You're also a stage actor and cabaret performer and staged an immersive multimedia cabaret show, LILIT. What is next for you?

Lilit Lesser: What is next? I don't know. I am currently just sort of resetting a little bit. It's been a year of a lot of grief, and a lot of pain. You know, as my dad said, acting work is great, take the bins out. I'm in a kind of taking the bins out proverbially and physically moment of my life. So, my Jewishness is very important to me. And there's a story that I often return to, that I think exemplifies the importance of tending to the practical things in one's life before you sort of get too caught up in anything else. And it goes like this.

Somebody comes to his rabbi and he says, I really want to progress spiritually, and I want to become a great tzaddik, you know, a righteous man. I feel like I'm not progressing and what am I doing wrong? And the rabbi says, okay, tell me what you do from when you wake up to when you go to bed. And the man says, oh, okay, well, of course, I wake up and the first thing I do is I daven, I pray, and I read my books. And the rabbi says, ah, there's your problem. That's why you're not progressing. The first thing you do when you wake up in the morning should be to feed your chickens. I think that's something that we can all learn from, the importance of feeding one's chickens.

Jace Lacob: Chickens. Feed the chickens. Start the day by feeding the chickens. Lilit Lesser, thank you so very much.

Lilit Lesser: Thank you. Thank you.

And now we’re back with Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light production researcher Kirsten Claiden-Yardley to discuss fact and fiction in Episode Three.

Jace Lacob: Cromwell attempts to marry his son Gregory to Jane Seymour's sister, Bess. Or is he just engineering a marriage for himself? There's a misunderstanding between the Seymours and Cromwell just over who the groom is in this arrangement, though ultimately Bess marries Gregory. Was there confusion at the time?

Kirsten Claiden-Yardley: Not that we have any evidence of. I mean, it's back again to that question of, is Cromwell planning as many marriages or attracting as much attention from women as it comes across in the show? There's not a huge amount of evidence for the progress of this marriage. Elizabeth Uhtred as she was at this time, around 1536, she's in Yorkshire, she's just been widowed, she has young children. She writes to Cromwell asking for his assistance. I said previously that we've got various examples of women asking for his help. She wants him to help her gain the property of a recently closed religious house to help her financial position.

There's no mention of marriage. A little while later she comes south and shortly afterwards, we begin to get rumors that there's going to be a marriage between her and Cromwell's son. And then eventually we get the report that the marriage has taken place. There's nothing to indicate that anyone thought that she was going to marry Cromwell or that she thought she was.

Jace Lacob: Henry nearly collapses while posing for his portrait by Hans Holbein. Did Henry's health decline to the point that he was unable to stand for any long duration?

Kirsten Claiden-Yardley: So, Henry's health is another area where we get sort of patchy reports every so often. We don't have a kind of continuous update on his health at regular intervals. It is clear that his health is deteriorating from 1536 when The Mirror and the Light picks up again from the end of the previous series. And what we're really seeing is the beginning of this sort of decline in his health which eventually is going to lead us to the hugely overweight Henry VIII that people know from the last couple of years of his reign.

So, what we do know is that he was supposed to actually go north after the Pilgrimage of Grace. And we have a letter where he writes to the Duke of Norfolk about the fact that he's not going to come to the north after all, and he gives all these excuses, but then he puts, for Norfolk's eyes only, keep to yourself that actually we've got this problem with the leg, with our legs, and we've been advised not to go so far at the hot time of year, in the summer. And then the following year, there's a report from the French ambassador that he's not speaking and he's black in the face and in great danger.

So we know that there's a couple of major health incidents. And we also know that he is relying increasingly on having a walking stick to help him at some points. By 1547, so at the end of his life, he has five different walking staffs of varying degrees of elaborate design and also some additional canes that sort of can travel around between places. So the sort of sense that I have for this time period is that it's an intermittent thing. So, sometimes he's needing his walking stick, sometimes he's fine, and I think that comes across quite well in the show, that you see him sometimes able to dance, but then afterwards you can see it's affecting him. Sometimes he's doing okay, sometimes standing up too long is causing him to collapse.

Jace Lacob: Kirsten Claiden-Yardley, thank you so very much.

Kirsten Claiden-Yardley: You’re welcome.

Next time, Queen Jane Seymour gives birth to a child.

CLIP

Henry: My lords, a son!

(cheering)

Join us next week as we talk with actor Damian Lewis about his riveting performance as King Henry VIII.

MASTERPIECE Newsletter

Sign up to get the latest news on your favorite dramas and mysteries, as well as exclusive content, video, sweepstakes and more.