|

The greatest geographical prize of its day was the search for the

fabled Northwest Passage through the island maze of Arctic Canada.

In 1845, Great Britain mounted an all-out assault with a lavishly

equipped expedition that was never heard from again. Then in the

early 1900s, a little-known Norwegian adventurer set forth in a

secondhand fishing boat and succeeded beyond all expectation. This

two-hour special answers the riddle of why one failed and the other

made it.

Hour one provides new details on the Franklin expedition, whose fate

was one of the great mysteries of the 19th century. Even today, the

manner of the expedition's demise is an ongoing detective story,

with clues and new interpretations still emerging over 150 years

after the explorers inexplicably disappeared. Hour two tells how

Roald Amundsen rewrote the book on Arctic exploration by stressing

simplicity and adaptability, and in the process completed the first

crossing of the Northwest Passage exactly 100 years ago. (To follow

the paths of both expeditions, see

Tracing the Routes.)

For centuries, explorers were convinced that a route could be found

through the islands and ice floes of northern Canada that would cut

months off the arduous sea voyage between Europe and the Pacific.

But every time someone tried, ice blocked the way. Determined to

succeed, the British Navy refitted two warships and assigned its

most experienced Arctic explorer, Sir John Franklin, to command. The

vessels were stocked with every convenience and a three-year

supply of food, much

of it canned—a relatively new technology.

Departing England in 1845, the 129 men seemingly vanished off the

face of the Earth. In 1848, the Navy dispatched the first of many

search parties, which eventually found the site of Franklin's first

wintering camp on Beechey Island in the High Arctic, including the

graves of three seamen. Modern tests show that the sailors died of

tuberculosis but were also suffering from lead poisoning, probably

caused by the solder used to seal their tinned food. The finding

suggests that the entire crew may have been affected to varying

degrees by excessive lead, which causes fatigue, confusion, and

paranoia.

Over the years, more searching has turned up a strange collection of

further clues (see, for one of the most telling,

The Note in the Cairn).

These point to an expedition trapped in the ice, slowly dying off,

desperately devising strategies to escape, and finally resorting to

cannibalism. Ironically, as Franklin's men were perishing, they had

periodic contact with native Inuit, who subsisted quite well in the

High Arctic thanks to their small numbers and highly evolved hunting

and survival skills. There is no evidence that the Franklin party

adopted any Inuit methods.

This lesson was not lost on Roald Amundsen, a young Norwegian whose

study of the Franklin disaster led him to an entirely different

approach. Instead of treating Arctic exploration as a siege, in

which a fully modern world is transported en masse to an unforgiving

place, Amundsen determined to travel light and live like the Inuit

as much as possible (see

My Life as an Explorer).

Where the Franklin expedition comprised over 100 men, Amundsen's

consisted of only seven; where Franklin commanded deep-water ships,

Amundsen piloted a battered, 30-year-old sealer that had proven its

worth at moving nimbly though shallows and ice floes; where

Franklin's men dragged a provision-filled lifeboat across the snow

when they had to go overland, Amundsen used an Inuit-style sled and

dogs.

Success came in August 1905, after two years battling the ice and

weather, when Amundsen encountered a whaling ship sailing from San

Francisco. (He overwintered once more before completing the Passage

in 1906.) Amundsen had proven that a path, albeit a difficult one,

existed across the top of the world—for anyone bold enough to

take it.

|

|

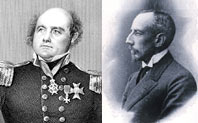

Sir John Franklin (left) and Roald Amundsen took

completely different approaches to tackling the

Northwest Passage, with widely divergent results.

|

|

|

Back to the Arctic

Passage homepage for more features on the Franklin and

Amundsen expeditions.

|

|

|