These Butt-Blasting Beetles Love to Cuddle

These bugs, which are known for spraying their noxious beetle juice when attacked, huddle in clusters that seem to break the rules of biology.

An aggregation of bombardier beetles. Though they look very similar, there are six species of Brachinus in this photo. Photo Credit: Chip Hedgcock, University of Arizona

You don’t want to piss off a bombardier beetle. When these brazen bugs feel threatened, they’ll turn their backs and take aim—and a boiling hot surge of noxious chemicals will erupt from their rear ends, dousing hapless attackers in a fiery, corrosive mist.

Wendy Moore is no stranger to the sting. She’s spent the last 18 years getting blasted by beetle juice. But time and time again, Moore has kept coming back for one simple reason: These ballistic bugs are breaking a cardinal rule of biology.

Moore’s findings, published today in PLOS ONE, detail how, like many other animals, bombardier beetles of the Brachinus genus will bed down with their friends after a long night on the hunt. One thing, however, sets these butt-blasting beetles apart: To them, company is company—no matter the species.

Across the tree of life, “family first” is a common strategy. In animal species prone to gathering, the vast majority of individuals will stick to their own kind. When multiple types of critters do cluster, it’s often because they’re all vying for the same food, water, or shelter; the resulting tussle over communal resources can create a bit of a warzone. Most species avoid the scrap by staking out their own territory and going it alone.

But it seems Brachinus bugs didn’t get the memo. After a long night of foraging for the drowned corpses of fellow insects—or, if they’re super lucky, the rotting carcass of an ill-fated frog or toad—these nocturnal beetles will begin groggily seeking refuge from the daylight. And not just any hovel will do. The most desirable real estate is concealed, dark, moist… and already packed with unrelated insect comrades. Sated from their twilight questing, Brachinus beetles will snooze the day away, contentedly spooning strangers.

When Moore, an entomologist at the University of Arizona, first unearthed one of these multispecies cuddle puddles, she was immediately intrigued.

“Normally, different species compete with one another—especially closely related ones,” Moore explains. “Finding close relatives all regularly aggregating together is somewhat of a mystery.”

To unravel the enigma, Moore and her graduate student, Jason Schaller, led a team of researchers to collect 59 batches of beetles—some composed of nearly 250 individual bugs—from the undersides of rocks speckling Arizona’s arid Sonoran Desert Region. At first glance, the beetle conglomerations seemed vastly homogeneous—what Moore calls a “dizzying array of red and blue.”

In fact, the 16 Brachinus species in central and southern Arizona all look so similar to each other, Schaller says, that it’s nearly impossible to tell them apart with an untrained eye. Only through the subtlest of traits—such as mild variations in the bugs’ exoskeleton, or the exact shape of the male’s internal penis, called an endophallus—could the researchers discern the exact species in question.

The team sequenced the bugs’ DNA to confirm that genetics corroborated anatomy. To their excitement, 71% of the beetle troupes the researchers amassed contained at least two species of Brachinus. Some assemblages had up to five types—and the congregations seemed to span even distantly related species on the diverse Brachinus tree.

Exactly how these aggregations formed still puzzled the researchers. So, they filmed the beetles’ nighttime shenanigans in the lab. Even in this artificial environment, when given the option to settle in perfectly comfortable unoccupied shelters, Brachinus bugs chose to cram themselves into multispecies throngs. What’s more, most of the insects showed no preference for closer relatives over distant ones; a few even seemed to deliberately avoid their own species to shack up with strangers.

As long as these brazen bugs didn’t have to weather the daylight alone, it hardly mattered what sort of company they kept. “It seems they really prefer to be together,” Moore explains. “It’s not just their environment—they’re actively seeking one another.”

The motivations behind these groupings are still a bit unclear, but Moore has a couple of theories, one of which brings us back to butts. After these beetles unleash a deluge of noxious lava from their backsides, they need about 24 to 36 hours to rest and recharge before they can fire again. This refractory period is risky, as it leaves them vulnerable to predators. If spent Brachinus beetles huddle with like-minded—and similarly-equipped—neighbors, however, they may be able to mooch off their defensive strategies.

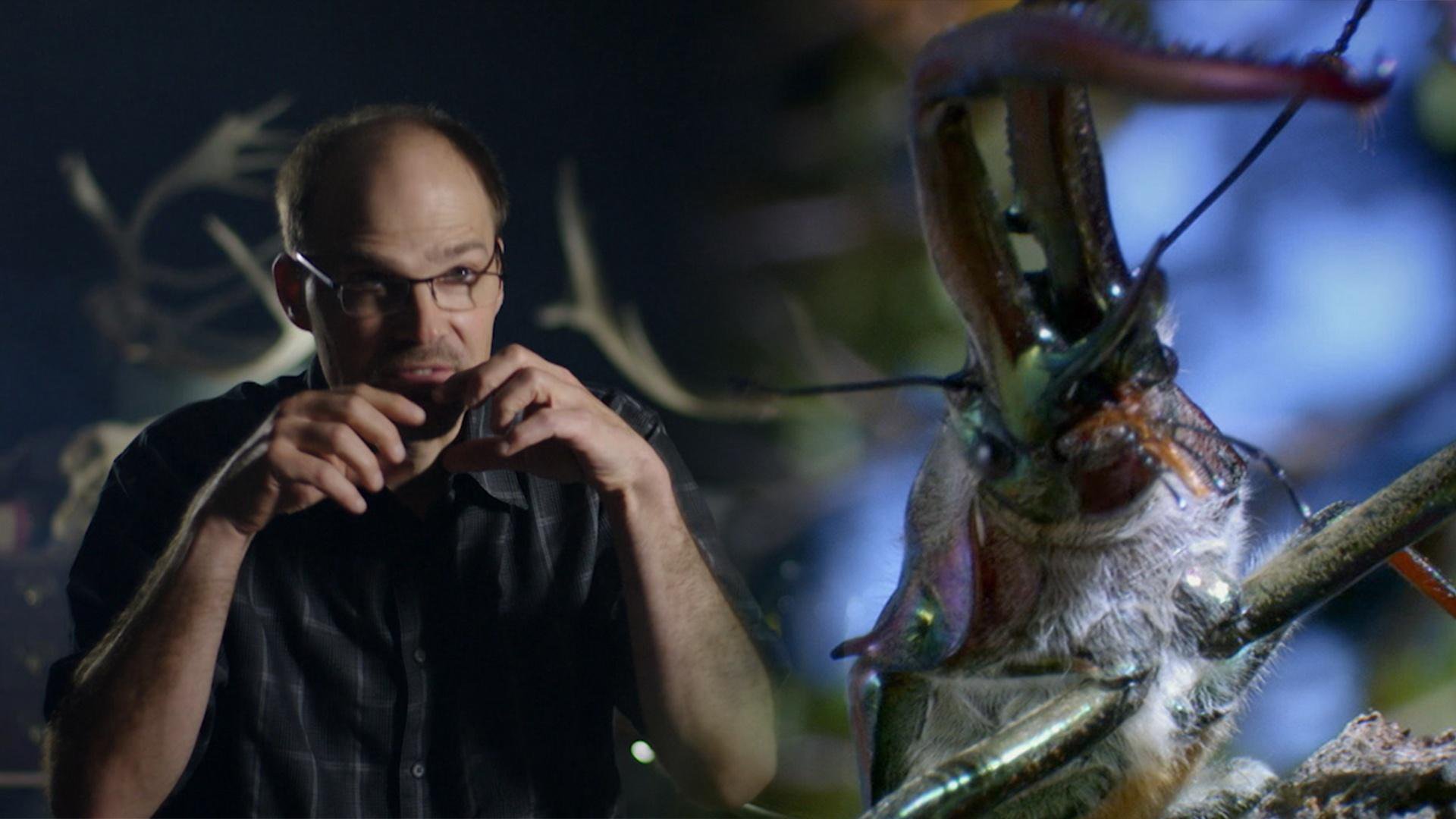

Study authors Jason Schaller and Wendy Moore collected bombardier beetles in Arizona to study the bugs' oddball tendency to shack up with other species. Photo Credit: Rick Brusca, University of Arizona

“The net advantage of all of this is very compelling to me,” says Laura Lavine, an entomologist at Washington State University who did not participate in the research. “By aggregating, these beetles get the downtime they need to recover.”

There may be other advantages to this snuggly behavior. Entomologist and carabid beetle expert James Liebherr of Cornell University, who was not involved with the newest find, theorizes that there could be an immune benefit to such aggregations. For instance, a ball of beetles could experience less exposure to dangerous fungi in the surrounding soil. Or, Liebherr adds, these bugs may have learned that insect congregations tend to signal the presence of choice waterfront property—far enough from streams that flooding isn’t imminent, but close enough to still snatch their water beetle prey from the banks.

Furthermore, the pitfalls normally associated with cross-species crowding may be significantly diminished for this particular group of beetles. As they segregated into different lineages, Brachinus subtypes settled into their own ways of life, each with its own preferred menu of prey and distinctive mating season. (Throughout their study, the researchers didn’t find any little hybrids born of these meetings en masse.)

Whatever the bugs’ rationale, Moore thinks there may be something to learn from their bizarre behavior. For all their chemical warfare, the moral of the Brachinus story is actually pretty heartwarming: As Moore puts it, “It’s better to make friends with close relatives and work together than to go it alone.”

Diversification, after all, has allowed many types of Brachinus to coexist peacefully in the same habitats, even when quarters get particularly close. Despite their ample arsenal of weaponry, these tough guys aren’t afraid to admit that they don’t like to sleep alone.