How Do Hurricanes Form?

Warm ocean waters fuel some of the most violent storms on Earth.

Few things beat a hurricane when it comes to showcasing nature’s fury. A hurricane’s gales alone can churn out about half as much energy as the global electrical generating capacity — not to mention the torrential flooding it leaves in its wake. But before a hurricane can grow to such a beastly size, its birth first requires a specific set of conditions.

Hurricanes, which scientists call “tropical cyclones,” vary in name by region: they're hurricanes in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific, but cyclones and typhoons elsewhere.

A tropical wave often kickstarts the whole process. These formations are not ocean waves, but instead an area of low atmospheric pressure that rolls off the African coast and moves westward through the tropics. They normally develop when hot air from the Sahara clashes with cooler, more humid air from the forested central Africa. Sometimes, thunderstorms follow.

The next ingredient is warm ocean water. As the tropical wave travels over waters above 26.5°C (about 80°F), warm, moist air starts rising upwards. This movement means there’s less air left near the surface — in other words, lower air pressure. Air molecules move from high to low pressure as they look for the path of least resistance, and as they do, the air from nearby areas with higher air pressure rushes in. Then, the new air becomes warm and moist and rises too.

Up in the sky, the water in the moist air cools off and condenses into clouds. The process releases heat, further powering the growing tempest. This happens over and over again until giant cumulonimbus clouds emerge. As long as winds near the top of the system are not too strong — which could scatter the structure of the blooming clouds — an epic storm will begin to brew. Once the storm’s winds exceed 74 mph, it’s officially a tropical cyclone.

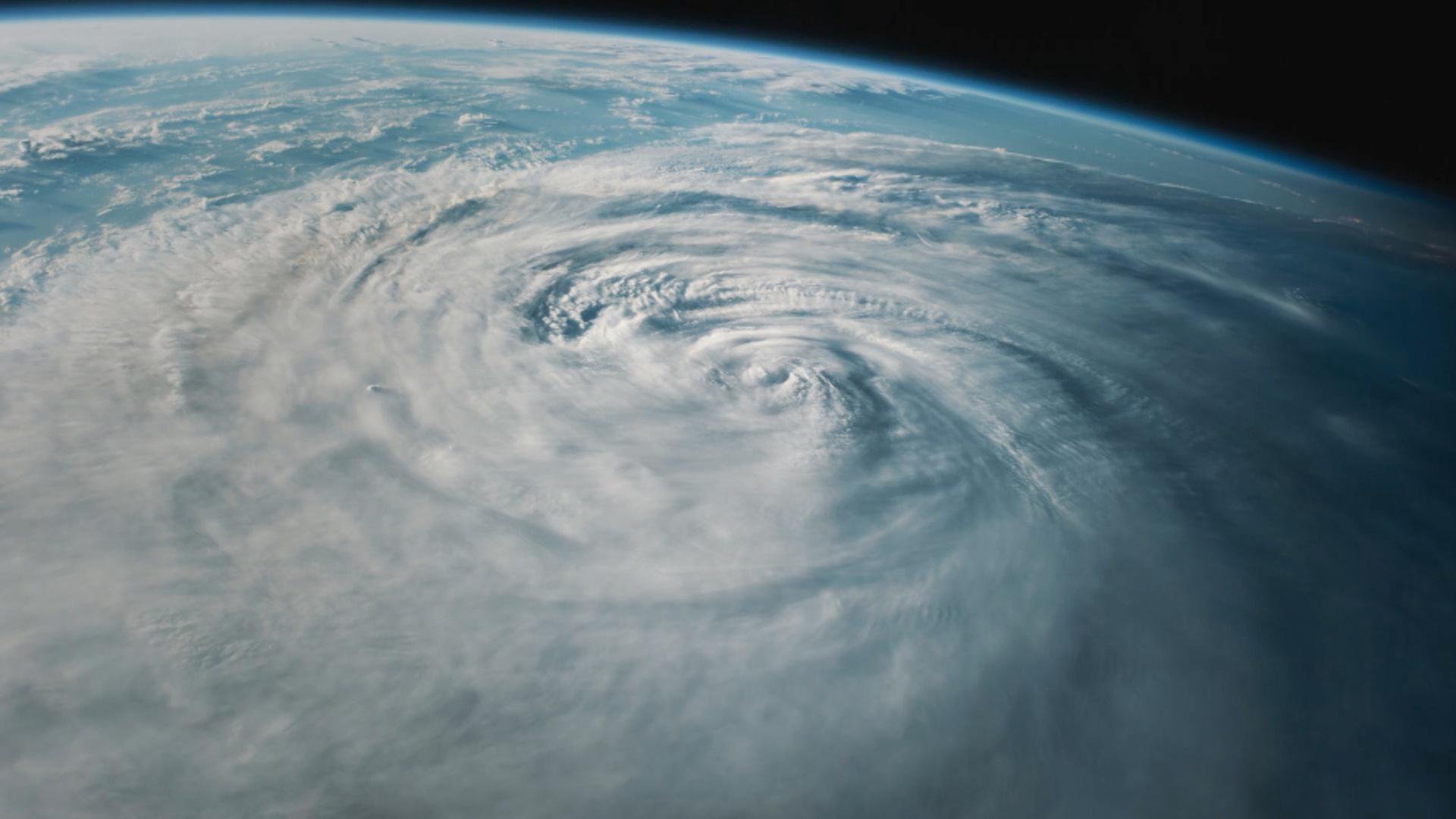

But why do hurricanes rotate? That’s due to something called the Coriolis effect. As Earth spins on its axis, an object on the equator must move much faster than an object by the poles. Rather than traveling in a straight line, winds coming to and from the poles are diverted. When different winds collide, they begin swirling. As a result, hurricanes spin clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Northern. In the center is the eye, an open area around which the rest of the storm rotates.

As long as hurricanes have warm ocean water to feed on, they will continue to amass speed and strength. Once they hit land, they can dump many inches of rain, down trees, and trigger dangerous storm surges, until eventually, a lack of fuel on land causes the hurricane to finally splutter out.