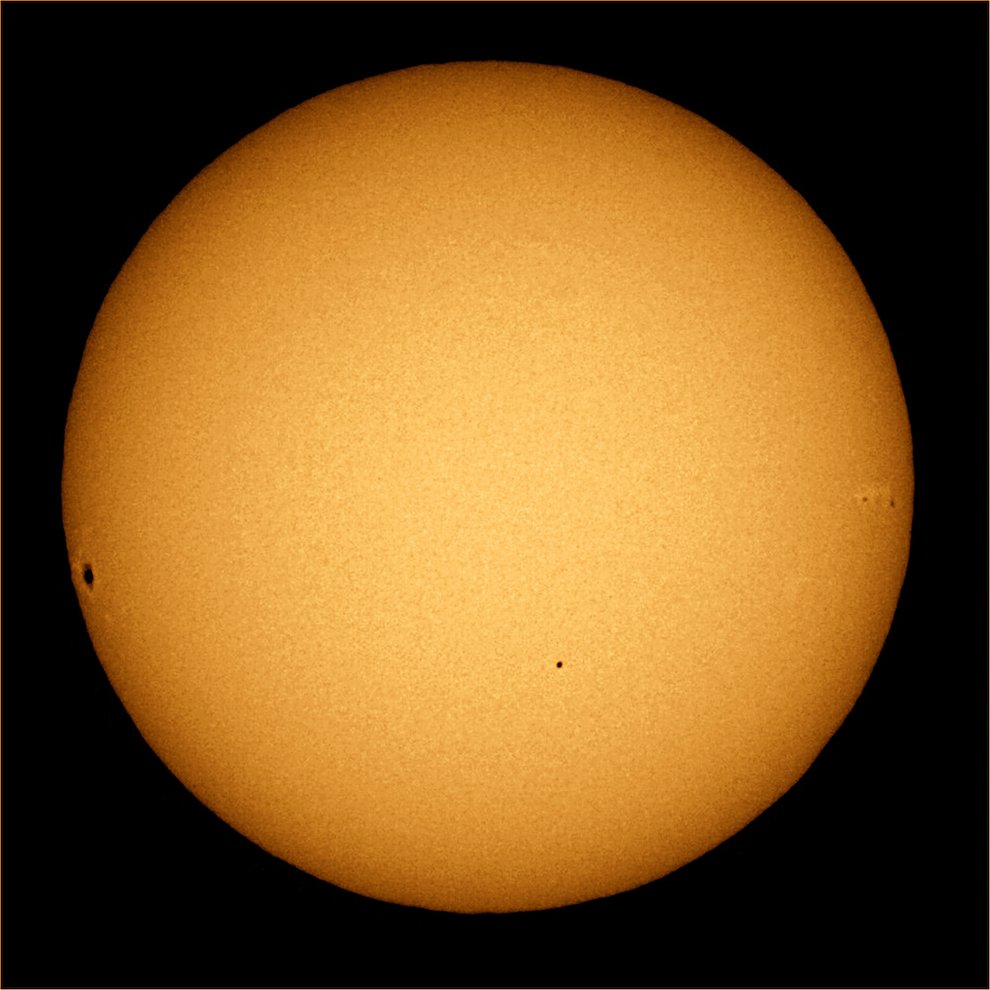

For the first time in 10 years, Mercury is transiting across the Sun. It’s a rare spectacle that occurs only about 13 times per century.

While the event is impossible—and very dangerous—to view with the naked eye, powerful telescopes equipped with solar filters are documenting the planet’s 7.5-hour journey. The next transit will not occur until 2019, and after that, 2032. Most parts of the globe are able to see it, with the exception of Australia, Japan, Indonesia, and Antarctica—which will be in darkness the entire time.

Mercury’s orbit is tilted by about 7 degrees with respect to Earth’s, so the three bodies align only once in a while. Here’s Phil Plait, writing for Slate (check out his article for great transit-viewing tips):

Because Mercury’s orbit is tilted, it appears to move “up and down” compared with Earth’s orbit. It crosses the plane of our orbit twice every Mercury year (those points on its orbit are called “nodes,” which are indicated in the illustration above), physically passing through one node or the other every 44 days or so (Mercury’s orbital period, its year, is about 88 days long). From Earth’s point of view, we see one or the other of Mercury’s nodes directly in line with the Sun twice per our year as well as we orbit the Sun. As it happens, those times are in May and November.

To see a transit, Mercury has to be positioned at one of its nodes at the same time Earth happens to be aligned such that the node is in front of the Sun. We then see Mercury in front of the Sun, and we get a transit!

Transits aren’t just awe-inspiring; they’re scientifically important. The 2003 and 2006 transits of Mercury helped experts determine the diameter of the Sun to an accuracy of 99.995%. And this year’s transit is proving just as beneficial—if not more so, especially because technology has advanced in the meantime.

Here’s Brad Plumer, writing for Vox:

During the May 9, 2016, transit, scientists at the Big Bear Solar Observatory in California will try to catch a glimpse of sodium in the planet’s exosphere, in order to better understand how it escapes the planet’s surface.

Also exciting: When Mercury passes in front of the sun, it causes a slight dip in the sun’s brightness. In recent decades, astronomers have realized that they can look for similar brightness dips in distant stars to detect the presence of exoplanets — other worlds that might even contain life.

NASA’s Kepler mission has found more than 1,000 exoplanets using this method. And scientists will be studying the dips in light during Mercury’s transit on May 9 to help better refine this method.

You can watch the event at NASA TV until its completion at 2:45 pm. Slooh is also broadcasting live from various telescopes worldwide: