|

|

This is a petal from the flower of the now-extinct species of

algarrobo tree whose resin was the source of all Dominican

amber. Without this single species of tree, the fabulously

rich community of ancient life captured in Dominican

amber—which includes the largest fossil gathering of

land-dwelling invertebrates in a tropical

environment—would not have been preserved. This tan

petal probably fell shortly after the flower opened.

|

|

|

Amber can record the most fleeting moments of forest life.

Here, pollen grains that were in the process of spilling out

of a falling algarrobo stamen spread like a handful of tossed

salt onto the surface of the sticky resin. Millions of years

later, the grains remain intact, with their original

protoplasm still inside.

|

|

|

Resembling a floral sea urchin, this "spiked ribbon" seed has

long golden ribbons extending out from a coiled hub. The

ribbons were likely used to aid the seed's dispersal, but

precisely how is unknown. The source plant of the seed, whose

diameter is just over a half an inch from ribbon tip to ribbon

tip, has not been identified.

|

|

|

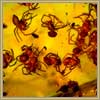

This fig wasp proves that plants of the fig genus existed in

the amber forest, even though no direct evidence of fig trees

or shrubs has turned up in Dominican amber. Each species of

fig today has its own specific wasp pollinator; experts

believe the same to have been true back then. Note also the

tiny wormlike creatures caught in the midst of escaping from

the wasp's body. Such nematodes today hitch a ride on fig

wasps to the next fig, where they multiply.

|

|

|

This extinct mushroom is the only known fossil tropical

mushroom ever found. One of the smallest members of the

so-called inky cap family, this specimen likely grew on the

bark of the algarrobo tree with others of its kind. When the

cinnamon-colored mushroom was overrun by a glob of resin, a

tiny mite grazing on its cap was entombed forever in the very

act of dining (see mite lower right).

|

|

|

Planthoppers were common in the amber forest. Like their

living relatives today, they used their needle-like beaks and

sucking mouthparts to draw out juices from within leaves. This

strikingly well-preserved planthopper was frozen in time so

quickly that it didn't even have time to retract its wings.

|

|

|

This "alligator-headed" planthopper indeed resembles its

reptilian namesake. And perhaps not just in name: scientists

have seen modern versions of such planthoppers resting with

their snouts high in the air, not unlike the stance that some

reptiles maintain. "Whether this behavior actually frightens

potential predators is unknown," writes George Poinar, Jr. in

his book The Amber Forest, "but why else would such a

posture evolve?"

|

|

|

Very few adult butterflies have been found in Dominican amber,

and all those, including this one, belong to the metalmark

family. Small and speckled, this orange-brown butterfly may

have mistaken a patch of resin on an algarrobo tree for a

tasty pool of sap. The sticky resin would have instantly

immobilized its wings, which possessed nowhere near the

strength needed to lift away.

|

|

|

It was not a good day for this moth fly, which had the bad

luck to be caught twice, first in a spider web and then in

resin. These delicate strands of spider silk are so well

preserved that experts have been able to identify their

spinner: a member of the spider family Araneidae.

|

|

|

These recently hatched spiderlings might have been on the

verge of "ballooning" when they were trapped. Ballooning is a

technique young spiders use to travel long distances quickly.

Spiderlings climb to an exposed location and begin generating

silk threads. When the threads reach a certain length, the

wind lifts both them and the spiderlings aloft before dropping

them to the ground again some distance away. Experts have

collected some spiders thousands of feet in the air, showing

how successful this tactic can be.

|

|

|

This army ant appears to have been out on a hunting mission

when it was entrapped. Judging from the wasp pupa beside it,

the worker had raided a wasp nest and was in the process of

carrying its prize back to the nest when it had the misfortune

of stepping or falling into a blob of resin.

|

|

|

Ant bugs like this one lie in wait on tree bark near foraging

ants. When hungry, they rear up and expose their undersides,

which release a secretion attractive to ants. As the ants

start feeding on the substance, they become lethargic from a

narcotic in the secretion. That's when the ant bug strikes,

savagely driving its beak into the weakened ant's body and

sucking out its life juices. The ant bug's hairs protect it

from any death-throe bites or scrabbles by its victim. Today,

ant bugs are extinct in the Western Hemisphere.

|

|

|

Other ant predators found on the algarrobo tree millions of

years ago were pseudoscorpions. When it succumbed to the

resin, this pseudoscorpion was in the midst of attacking an

ant. Victory for the assailant was not a foregone conclusion,

however; ants sometimes win such battles and destroy their

attackers.

|

|

|

Parasitic beetles are uncommon today, but their natural

history tells us how beetles like this one with its bizarre,

antler-like lobes thrived in the amber forest. Though social

wasps are one of its prey, such beetles do not have to

encounter a wasp in order to parasitize it. Instead, the

beetle lays its eggs on or near flowers. When its larvae

hatch, they wait for a wasp to alight on the flower to imbibe

nectar. The larvae then grab hold of the wasp and hitch a ride

back to its nest, where they transform into grubs and dine on

wasp larvae. Later the grubs pupate in the soil and then go on

to continue the cycle.

|

|

|

Lizards in amber are extremely rare—so rare that a

single intact specimen can bring hundreds of thousands of

dollars on the collectors' market. This gecko may have been

eyeing a tasty insect feeding on the leaf seen here when it

attacked the bug and unintentionally brought down the leaf and

itself into a mass of resin. The victim might still remain

inside the gecko's throat.

|

|

|

No entire birds have ever been found in amber, but parts of

them have, including this feather. While a variety of feathers

are known from amber, this is the only one that experts have

identified. It belonged to a small bird in the woodpecker

family known as a piculet. A relative of this bird called the

Antillean piculet still lives in the Dominican Republic today.

|

|

|

As with birds, no intact mammals have turned up in amber, but

traces of them have. Experts were able to guess what creature

left behind this tuft of hair both by examining microscopic

features in the strands and by identifying two

parasites—a fur mite and a fur beetle—found in the

hairs. These clues led them to conclude that this tuft

belonged to a rodent, possibly an extinct relative of the

hutia. Hutias are small, secretive creatures still living in

the Caribbean area today, millions of years after the owner of

this fur perhaps brushed up against an algarrobo, entombing a

swatch of its hair for eternity.

|