Space Race Time Line

After the fall of Nazi Germany at the end of World War II, the

United States and the Soviet Union emerged as superpowers,

each striving for primacy on a global scale. As rocket

technology improved and spaceflight seemed possible, the

dueling forces also set their sights on reaching and

controlling space. Headlines of the 1950s and '60s seemed to

indicate that the Soviet Union was light-years ahead of the

U.S. throughout much of the space race. But behind the scenes,

a very different story was unfolding. Recently released

documents reveal secret military plans, cover-ups, and covert

spy missions that were part of humankind's ambitious journey

into orbit and beyond. In this time line, explore the Cold

War's secret space race.—Rima Chaddha

Left to right: Soviet Premier Nikolai Bulganin, U.S.

President Dwight Eisenhower, French Premier Edgar Faure,

and British Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden on the eve

of the 1955 Geneva conference during which Eisenhower

introduced "Open Skies"

|

|

July 1955

Open Skies proposed

Following World War II, the United States and the Soviet

Union entered into the Cold War game of spy-versus-spy

that ultimately led to the space race. Americans were

still deeply unsettled by the 1941 attack on Pearl

Harbor, and the U.S. government wanted to arrange

flyovers of U.S.S.R. territory to learn what they could

about Soviet arms. Equally, the Soviets wanted to spy on

the United States but strived to keep their depleted

military resources secret. In July 1955, President

Dwight Eisenhower proposed an "Open Skies" policy

whereby either nation would be allowed to fly

reconnaissance aircraft over the other. When the Soviet

Union rejected the proposal, Eisenhower sought other

ways to gather intelligence. On July 29, he announced

that the United States would begin work on a scientific

satellite. The Soviet Union immediately announced that

it too would launch a satellite.

|

A technician puts the finishing touches on Sputnik 1

shortly before the satellite's three-week orbit.

|

|

October 1957

Sputnik 1

In a top-secret report, Eisenhower's Science Advisory

Committee urged him to consider launching non-military

satellites, which, unlike planes, could travel over

enemy terrain without risk of being shot down. These

satellites would thus establish a precedent for "freedom

of space," conducting flyovers above the planet's

atmosphere without permission or negative consequences.

While to the public the satellite program was a purely

scientific effort, both Eisenhower and the Soviet

leadership understood the potential for reconnaissance:

Safe from attack, an orbiting satellite could

theoretically observe anything on the ground. Both

nations endeavored to perfect their satellites and

launch first, and on October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union

sent Sputnik 1 into orbit.

|

Three men responsible for the Explorer 1 raise a model

of the satellite at a 1958 press conference. (Left to

right: William Pickering, James Van Allen, and Wernher

von Braun)

|

|

January 1958

Explorer 1

Just a month after propelling the first satellite into

space, the Soviet Union had made headlines again with

Sputnik 2, which sent the first animal, a dog, into

orbit. With two failed launch attempts in the United

States, many Americans wrongly believed Eisenhower had

failed to recognize the importance of space efforts. But

on January 31, 1958, America began to catch up publicly

to the Soviet Union. The U.S. satellite aptly named

Explorer 1 not only reached orbit but also managed to

gather useful scientific data. In July, Eisenhower

announced the formation of NASA, a federal agency that

would be devoted to exploring space. Meanwhile, students

nationwide benefited from new programs adopted to

improve science and math education.

|

Luna 3 snapped 29 images in total, capturing the first

shots ever of the far side of the moon.

|

|

1959

Reaching for the moon

By 1959, both countries had set their sights on a new

symbolic goal—being first to the moon. The Soviets

launched Luna 1 in January, and although the craft

missed its target, it became the first to fly beyond

Earth's orbit and the first to orbit the sun. In March,

the United States launched Pioneer 4 toward the moon,

but it too missed and fell into solar orbit. Finally,

Luna 2 reached the moon's surface, and on October 4,

exactly two years after Sputnik, Luna 3 performed a

flyby and photographed most of the moon's far side. The

Soviets now appeared to be winning the lunar phase of

the space race, but if they intended to send a manned

mission to the moon, they were keeping the plans secret.

|

This 1967 Corona photograph, a test of the satellite's

spying capability, offers a detailed view of the

Pentagon in Washington, D.C.

|

|

1960

Spy photos from space

As scientists in both nations worked to improve rocket

and satellite technology, plans for spy missions were

already well under way. Since 1959, the United States

had been developing a series of secret military

reconnaissance satellites together codenamed Corona. But

because rocket launches were difficult to hide, the U.S.

government disguised early Corona missions as part of a

publicly known research program called Discoverer. The

Soviet Union lagged two years behind with their own

Zenit spy satellites, which were ostensibly part of the

Kosmos research program. The Zenits carried standard

film cameras similar to those found in rival Coronas

and, over time, they became powerful enough to

photograph objects as small as passenger cars on the

ground.

|

Dressed in space gear, Yuri Gagarin rides a bus to the

Vostok 1 launch site.

|

|

April 1961

Gagarin reaches space

On April 12, 1961, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin flew into

orbit with the Vostok 1 and became the first man in

space. The Soviets had once again beaten the Americans

by mere weeks. Yet Gagarin's flight, a driving impetus

behind President John F. Kennedy's May announcement that

American astronauts would reach the moon by the end of

the decade, was not as flawless as the Soviets claimed.

Nearing the end of its orbit, Gagarin's craft began

spinning out of control. During the ensuing 10-minute

panic, his commander, who was on the ground, scribbled

in his notes phrases like "sudden impact," "emergency

situation," and "Malfunction!!!" Gagarin himself would

later confirm the near-accident, which remained hidden

to the world for decades.

|

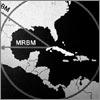

This CIA map revealed the potential reach of

medium-range and intermediate-range ballistic missiles

if launched from Cuba.

|

|

October 1962

Cuban Missile Crisis

Tensions rose dramatically in October 1962, two months

after the first Zenit photographs reached Earth, when an

American reconnaissance aircraft flying over Cuba

photographed Soviet nuclear missile sites under

construction just 90 miles from the U.S. coast. The

Americans had built similar bases at the Turkish-Soviet

border, and if one nation chose to strike, the other

could easily retaliate. The Cuban Missile Crisis lasted

only two weeks but had significant consequences.

Realizing the potential for a nuclear war, both nations

removed their weapons and secretly sought ways to

further improve their intelligence-gathering

capabilities.

|

A 1960 conceptual drawing of the Manned Orbiting

Laboratory

|

|

1963

Manned Orbiting Laboratory

On December 10, 1963, the United States announced plans

to build the Manned Orbiting Laboratory, a military

space station designated for scientific research. The

MOL's covert mission, however, was to enable astronaut

spies to take better and more detailed photographs of

the Soviet Union and its allies than ever before. The

Corona satellites in use in the early 1960s were not

sophisticated enough to seek out and zoom in on

specified targets. But as computerized reconnaissance

technology improved, the need for an expensive manned

mission receded. The United States finally abandoned the

MOL program in June 1969, one month before NASA's Apollo

11 landed the first men on the moon.

|

A reflection of the lunar module can be seen in Buzz

Aldrin's visor as he stands on the moon. (Inset: a

Krechet spacesuit)

|

|

1969

Moon rockets

To many, the space race ended when Neil Armstrong and

Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin set foot on the moon. This time, the

Soviets were far behind. While the world marveled at the

United States' Saturn 5 "moon rocket," which sent the

astronauts' Apollo 11 craft into space, the Soviets had

secretly been working on their own version, the N-1.

Although the N-1 failed to launch, the rocket engineer

who led the program, Vasily Mishin, kept private diaries

listing items and operations needed for a manned lunar

landing. These included specialized tools, maps, and

spacesuits. The Soviets had even built a prototype moon

suit, called the Krechet ("Golden Falcon").

|

Three crews boarded Skylab between 1973 and 1974, with

the longest mission lasting nearly three months.

|

|

1973

Skylab

By 1973, the MOL was little more than a memory to the

few Americans who knew about it. But as the potential to

sustain human life in space increased, so did the desire

to develop a manned space station. A special advisory

group to President Richard Nixon offered suggestions for

such a station, which was to be occupied permanently, as

part of a post-moon-landing plan for American space

travel. Using some remaining hardware from the

soon-to-be-cancelled Apollo program, NASA developed

Skylab, which launched in May. Skylab remained in orbit

for six years, and experiments conducted aboard the

craft obtained vast amounts of scientific data and

demonstrated that humans could live and work

productively in space for months at a time.

|

Cosmonauts test a pressure suit worn aboard a Salyut

space station orbiting Earth.

|

|

1974

Space weapons

Illustrating the Cold War's true potential dangers, both

the United States and the Soviet Union made covert plans

to bring weapons ranging from cannons to laser guns into

space. In 1974, the Soviet Union launched the Salyut 3

space station, code-named Almaz, which secretly carried

a 23-mm Nudelmann aircraft cannon. According to Soviet

cosmonauts, tests run on this very first space gun were

a success—the cannon even destroyed a target

satellite. Although Almaz tracked several American

spacecraft, including Skylab, the Soviets never attacked

any of them. More benign Soviet stations such as the

Salyut 4 were utilized in research and tests similar to

those conducted on Skylab.

|

The Apollo-Soyuz plaque, engraved in both English and

Russian, was created to commemorate this first joint

effort.

|

|

July 1975

Apollo-Soyuz

Marking a temporary thaw in the Cold War, the United

States and the Soviet Union embarked on their first

joint space venture in July 1975. Astronauts and

cosmonauts docked the last Apollo spacecraft with the

Soviet vessel Soyuz, and the crews visited each other's

craft and shared meals. At ground control centers in

Moscow and Houston, scientists cooperated in tracking

data and communications. Although tensions between the

two nations remained—the 1980s saw President

Ronald Reagan's "Star Wars" plans to intercept Soviet

missiles from space, for instance—Apollo-Soyuz set

the stage for later collaborative space efforts,

including the International Space Station. This research

facility, currently being assembled in orbit, will be

open to cosmonauts and astronauts worldwide.

|

|

We recommend you visit the

interactive version. The text to the left is provided for printing purposes.

|