|

|

NOVA scienceNOW: Profile: James McLurkin

|

|

|

Viewing Ideas

|

|

Before Watching

-

Many of your students have never experienced life without

computers. Help them develop a clearer understanding of their

personal, and society's, dependence on computers. Have them

brainstorm a list of the ways computers are used today. Ask

them: What roles do computers play in our lives? (Some examples

include personal computers that help us write research papers or

e-mail, calculators that make number crunching quick and easy,

and computer chips that help our cars, microwave ovens, VCRs,

cell phones, and other appliances run.) How would our lives

change if computers did not exist?

Then, have students brainstorm a list of city and state agencies

with back-up systems that allow them to continue to provide

critical services in the event of a power or computer failure

(airlines, hospitals, nuclear power plants, fire departments,

etc.).

Finally, you might also have students interview older caregivers

or friends, asking how they perform tasks for which we now use

computers.

-

It used to be that Christmas tree light strings were wired bulb

to bulb. If any bulb burned out, the whole string went dark. The

more bulbs in the string, the more likely the string would fail

because the additional bulbs meant more chances of failure. One

of the first electronic computers was ENIAC, first operated on

behalf of the U.S. Army in 1944. Like the old Christmas tree

lights, ENIAC's 19,000 vacuum tubes were a constant source of

failure. Technicians continuously circulated among its banks to

change burned-out tubes as it operated. Help students understand

how parallel and series circuits work.

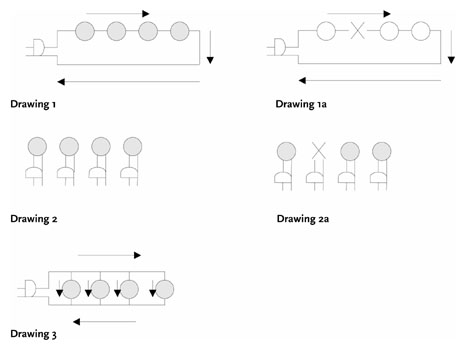

Sketch Drawing 1 on the board. Have students trace the flow of

electricity from one blade of the plug through all four light

bulbs and back to the other blade of the plug. Next, erase one

of the bulbs and replace it with a large X (see Drawing 1a). Ask

whether the other bulbs would be able to light. (No.) Ask why

all bulbs would be dark. (Pathway is broken.) Explain that this

is a series circuit. Ask students to theorize why early versions

of ENIAC would only run for about 20 minutes before a failure.

(Many vacuum tubes create many opportunities for the pathway to

break.)

Sketch Drawing 2 next to Drawing 1. Explain that each bulb has

its own plug. Now, erase one of the bulbs and replace it with a

large X (see Drawing 2a). Ask whether the other bulbs would be

able to light. (Yes.) Ask why the other bulbs would light. (They

are on separate pathways.)

Ask students to design a circuit that has only one plug, but all

bulbs have a separate pathway to that plug. Have students share

their designs. Sketch Drawing 3 after students have had a chance

to try the challenge.

Explain that Drawing 3 shows a parallel circuit. Ask students

which circuit, series or parallel, is most likely to stay lit if

a bulb burns out. Explain that James McLurkin designs computers

that are made of many small computers working together. Ask

whether McLurkin's computer robots are more like a series or a

parallel circuit. (Parallel: Many robots represent many pathways

to accomplish a task; when one fails, the others continue the

task.)

-

Today, computers seem to effortlessly perform very complicated

tasks. These tasks are actually based on thousands or even

millions of simple step-by-step instructions painstakingly

written by computer programmers. A single bad or missing

instruction reveals that computers are really just mindless

devices.

List the following common tasks on the board: making a peanut

butter and jelly sandwich, making chocolate milk from syrup, and

brushing your teeth. Divide your class into four-member teams.

Have each team choose one of the tasks. Explain that each

student should write a set of instructions to successfully

complete the chosen task. To simulate programming commands, tell

students to write brief but clear instructions with only one

action per line. Tell the teams that when they finish, each

writer should read his or her instructions one step at a time

while another team member acts them out. The remaining team

members should look for any missing instructions or instructions

that can be misinterpreted. For example, "Put the peanut butter

on the bread" could lead to a jar sitting on an unwrapped loaf

of bread. Ask teams to share some of the hilarious programming

errors that they detected. In what ways is programming easy and

difficult at the same time? How might you keep track of the

instructions in a program that contained 1,000 lines?

After Watching

-

James McLurkin says the first rule about robots is that they are

"profoundly stupid." They must be carefully and painstakingly

programmed to be successful. His robots were unable to complete

a music demonstration because of a programming error. Ask

students to give examples of robots they are familiar with from

books, television, and movies. How do McLurkin's real-world

robots compare with these fictional robots?

-

McLurkin is very careful and schedules every detail of his

activities on his computer, but it doesn't always help him stay

on schedule. Why does this happen? Have students create

flowcharts (or a step-by-step pictorial representation) of their

day. First, discuss different ways students can create a

flowchart. (It could be simply a series of boxes containing

times and tasks connected by arrows.) Ask them to make a

flowchart that includes everything they think they will do the

next day. The flowchart should be fairly detailed. As they go

through the day, have them keep a timed log of what they

actually do. Then, have them compare the real-life log to

their flowchart. Were they behind? Were they ahead? On schedule?

Was there duplicate effort or unnecessary tasks? What

adjustments do they need to make in their schedules to make

their days more efficient and the flowchart more accurate? Make

a new flowchart for the following day and test it out. Did their

efficiency increase? What was it like to have a flowchart for

their life? How, if at all, did it change their life?

-

This activity demonstrates how a large number of students

(computers) can be programmed so that simple arithmetic

operations can be carried out without anyone coordinating the

process. (You may want to review the

Data Flow Diagram

before doing the activity with students in order to see how

information travels between groups of students in the activity.)

-

Put students into the following four groups:

- The Result

- First Number

- Second Number

- Operation

-

Tell the students that you will give them a copy of their

group's written instructions to review. You will then say

"RUN," at which point they should stand up and execute the

written instructions. After their group has performed its

task, they should continue to display the results so other

groups can see them.

-

To "program" the groups, copy the Instructions for Groups

(PDF

or

HTML) handout. Cut up each group's instructions and distribute

it to the appropriate group.

-

Review each group's instructions with them and ask them to

demonstrate their programming.

-

Give the First and Second Number Groups a number and the

Operation Group an operation (for example, 14 - 8 = 6).

Remember that the largest number that can be displayed by

any group is twice its membership.

-

Explain that after this activity begins, students are not to

communicate with each other. They are to carefully follow

all of the programming (instructions), observe, and react.

-

Start the calculation by saying "RUN." Assist the first

attempt, as necessary.

-

Once the groups have completed their programming, count the

Result Group hands and share the original operation and the

results. Repeat with a new arithmetic operation, as desired.

After the first run, you can test the resiliency of your

distributed computer by asking several students to sit down

during a run. Does the computer adapt and correct for these

losses? Ask students how James McLurkin's small computers are

like this distributed class computer. How would using 24

distributed computer robots be more effective than a single,

very smart robot mapping a cave system or looking for a lost

child?

|

|