Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: More now on our top story. Ukrainians are breathing a sigh of relief as the Senate passes its long-awaited aid bill. Hallelujah was the response from their foreign minister, Dmytro Kuleba. He said that to “The Guardian.” But he also warned that Russia is out shelling Ukraine 10 to 1, and, “No single package can stop the Russians.” Author and staff writer at “The Atlantic,” Anne Applebaum’s latest piece is called, “The GOP’s Pro-Russia Caucus Lost. Now, Ukraine Has to Win.” And she joins Walter Isaacson to discuss how.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WALTER ISAACSON, CO-HOST, AMANPOUR AND CO.: Thank you, Christiane. And Anne Applebaum, welcome back to the show.

ANNE APPLEBAUM, STAFF WRITER, THE ATLANTIC: Thank you.

ISAACSON: After a torturous few months, the House has passed, and then last night, the Senate passed a Ukraine aid bill. The president is signing it. And you begin your piece about it with this, “It’s not too late, because it’s never too late.” Well, sort of as a historian, I’m not sure about that. In history, we often have things that are too little, too late. How are you so confident that this isn’t a little bit too late?

APPLEBAUM: Well, I think the point is that, of course, it’s too late. If the Ukrainians had had this money and they’d had the weapons, more importantly, months ago, then there are Ukrainian cities that wouldn’t have lost their power generation. There were Ukrainians — it would be — Ukrainians would still be alive. There would be soldiers who would still be fighting and territory not lost. But by writing that I meant to say that the — you know, the future of Ukraine will go on being in play no matter what we do. In other words, they can suffer defeats or they could lose land, but they aren’t going to stop fighting. And so, having the support of the United States and having the confidence of being part of a larger alliance, it can help — still help turn the war around and still — can still help them achieve victory. So, I meant by saying that there’s always a second chance, and I think they’ve got it now.

ISAACSON: And you say that once the U.S. money starts flowing again, the dynamics of the war will change. Tell me what you think the dynamics, how they will change.

APPLEBAUM: So, of course, there’s a military dynamic. So, with more ammunition and with more weapons, the Ukrainians won’t lose territory. They’ll be able to protect their cities. But there’s also a very, very important psychological dynamic. In other words, the Russians still think that they’re going to win by outlasting us, that they will just keep fighting until we get tired. And part of their war effort has been a huge propaganda effort to convince Americans, to convince Europeans that the Ukrainians can’t do it, that they’re weak, that they’re corrupt, that they’re divided and to persuade us not to help them. And, of course, for them, that’s the easiest way to win, is have is have Ukraine’s allies give up. And so, by taking this decision, by allotting this amount of money and especially, as I say, this amount of weaponry, we change that psychological dynamic. So, now, the Russians aren’t on — don’t think of themselves on a path to win easily, they now know that there’s this — there’s renewed western support, that there is renewed western effort behind Ukraine. And so, this a — you know, like all wars, this war has an important psychological element. And the passing of this bill means that the United States is not yet so divided and not yet so isolationist and not yet so easily persuaded by Russian propaganda, you know, as to allow the Russians to win without a struggle. And so, the Russians are now on a much — suddenly facing a much steeper uphill path.

ISAACSON: This change in the psychological dynamic where Russia realizes we’re not so divided, that we will — and we’re going to continue to support for a while Ukraine, does that also change the diplomatic dynamic or is there any diplomatic dynamic to be had?

APPLEBAUM: So, there is a diplomatic dynamic in that, of course, there are behind the scenes conversations. And of course, people are constantly testing the waters to see whether the Russians are willing to give up or retreat or even just stop fighting. Up until now, it’s been pretty clear that Putin has not wanted to stop. And this why all these conversations and comments about how, you know, the Ukrainians should — they should change — exchange land for peace or they should negotiate or they should stop have really been a bit pointless because until the Russians decide to stop fighting, until they decide they don’t want to continue the war, then the war won’t end. In other words, in order to negotiate, you need to have someone to negotiate with. And until now, there’s no one to negotiate with. Because Putin’s goal in this war is not just territory. He doesn’t need any more land. Russia is a very large country as it is. His goal has been to eliminate Ukraine as a state, to make it unviable, to perhaps to wipe it entirely off the map, certainly to capture and control its major cities, perhaps to have a kind of Russian controlled government in Ukraine, but in any case, to have it cease to exist as an independent entity. And it’s only when they give up that goal, when they say, right, we’re not going to eliminate Ukraine from the map. It’s not going to happen. Their alliances are too powerful. Their will is too strong. Their military is too innovative, whatever is the reason, or we’re paying too high a price, then they will stop. And so, yes, this decision, I would think, pushes us farther along that path.

ISAACSON: And so, do you think that there’s a possibility of a major new diplomatic initiative? You know Russia pretty well, or do you think that’s just hopeless right now?

APPLEBAUM: I mean, eventually, there will be a diplomatic initiative. Eventually the war will end with a negotiation of some kind. You know, my understanding right now is that the Russians are waiting for the results of the U.S. election. They’re hoping that if Donald Trump becomes president a second time, that he will abandon Ukraine and, you know, perhaps partition Ukraine, or there are many scenarios out there, and that they will be in that way.

ISAACSON: But don’t you think that has some validity to it, that certainly Trump would do that, and if you were Russia, wouldn’t you wait and see?

APPLEBAUM: So, yes, I think there’s validity to it, and he’s — and Trump has certainly given that impression, and people around him are also giving off that impression, and there are even open conversations about it that I’ve heard. So, yes, of course, that’s why the Russians are waiting. You know, by the very delay of the aid, the delay of this bill that has just been passed, the delay was, as most people understand it, was essentially caused by Trump. It was Trump’s pressure on the Republicans and in the House and on Republicans in Congress that — you know, that led to the delay. So, Trump is already seen as playing a role in this conversation.

ISAACSON: Why do you think Trump didn’t step in when Speaker Mike Johnson put it up? He could have said something in the past week or two, and he let it pass.

APPLEBAUM: Trump appears to have been convinced that it would be a bad idea for Ukraine to lose, that he might be blamed for it. And it — you know, for reasons I don’t have, you know, insight into Trump’s brain, maybe he’s distracted by other things at the moment. But he appears to have decided that it was OK, and that may have been part of Mike Johnson’s decision.

ISAACSON: Earlier this month, British Foreign Secretary Cameron and I think the Polish president all met with Donald Trump. Your husband is the foreign minister of Poland. Tell me what you think the general significance of these meetings are. Are they trying to prepare for the possible second term of — next term of a Trump presidency?

APPLEBAUM: No. So, in the case of both Cameron and the Polish president, who’s, by the way, he’s from a different part of Polish politics than my husband. But so — that’s just so that you know. But the point of those meetings was to talk to Trump about Ukraine in order to persuade him, to allow Mike Johnson to put this bill on the floor. And there have been several other meetings similar that I’m aware of as well. And so, I think these are more about that. I mean, that we are in a strange position where the person who is the Republican candidate and perhaps the next president is playing a clear role in U.S. foreign policy, you know, is clear. I don’t think we’ve ever been in a position before where an out of power former president has so much influence over Congress and over its decision, and they’re trying to convince him to — in the case of those two leaders, they’re trying to convince him — you know, to allow weapons to go to Ukraine.

ISAACSON: You know, a lot of people refer to the GOP holdouts, people like Marjorie Taylor Greene, as ultra conservatives. I’ve never quite understood that designation. I think in your piece, you call them the pro-Russian part of the Republican Party, or pro-Kremlin, pro-Moscow. Why — you know, why do you think that’s a better description?

APPLEBAUM: So, conservative implies that you’re conserving something, that you’re — you know, in the United States it implies that you’re conserving some kind of American tradition. I don’t see that advocating on behalf of a foreign dictatorship is conservative. It seems radical to me or extremist, or as I wrote, I mean, you could just call it pro-Russian, which is which is what it is. Marjorie Taylor Greene comes to Congress and produces, you know, photographs and material that come directly from Russian propaganda sites. And she, you know, describing Ukrainians as Nazis and so on. She actually uses the language of Russian propaganda, you know, in Congress, in public. And that’s — that doesn’t seem very conservative to me. It seems extremist and pro-Russian. And so, you’re absolutely right to point to this misuse of language, this misuse of the word conservative to describe her and the others in that group who are now radically pro-Russian.

ISAACSON: Let me read you a quote from your piece. You say, “Anyone who seeks to manipulate the foreign policy of the United States, whether it be the tin-pot autocrat in Hungary or the Communist Party of China, now knows that a carefully designed propaganda campaign, when targeted at the right people, can succeed.” You’re an expert in information, misinformation, and propaganda targeting, what do you mean by that? Do you think that the pro-Russian Republicans were manipulated by propaganda campaigns?

APPLEBAUM: It is certainly the case that Russian propaganda was used by members of the U.S. Congress in their public debates and even in private conversations. Republican Senator Thom Tillis has described how he heard his colleagues in debate about Ukraine using a story that we know is fake. This a story that President Zelenskyy owns two yachts, OK, there was a photograph of the yachts circulating on the internet and the yachts actually belong to other people and so on. I mean, this was an easily disproved fake. And yet, there were Republican senators saying, we shouldn’t give this aid money to Ukraine because it will just be used to buy some more yachts. And this really extraordinary, this means that there’s a direct path from an invented story to the U.S. Congress, probably via, you know, some kind of internet echo chamber in which Russian and far right propaganda mix, but it is now possible to get those ideas into the heads of U.S. Congress. People — they aren’t resistant to it in a way they might once have been. And this a — this by itself was an incredible success. You know, the Russians at least managed to delay the aid package for a year. By using — by targeting this kind of — these kinds of lies, by creating a campaign around the hopelessness of the war, around the pointlessness of supporting Ukraine. And of course, there still are both senators and congressmen using that language. But they did it successfully. And it has to be the case that others will look at it and say, oh, it’s that easy. You know, you can — if you can get Congress to go along with your made-up stories, then it’s certainly worth trying. I mean, sometimes the Russian efforts to manipulate conversations, whether it’s in the U.S. or anywhere else, can be a little nutty. I mean, it’s almost like they throw spaghetti at the wall and they just see what sticks. But this was a really carefully targeted, careful campaign. And as I said, yes, make it look hopeless. Ukraine can’t win. Ukrainians are corrupt. Ukraine isn’t democratic. You know, we’re — the Ukrainians are Nazis. And all of that was eventually used by actual members of Congress in their public statements. So, we know that it got through to them.

ISAACSON: Well, let me push back on that just a little bit because among the people who use that in the Senate, and you’ve been very critical of him for doing it, is Ohio Senator J.D. Vance. And he talks about the fact that Ukraine needs more soldiers than it can field even if it has draconian conscription methods, and that Ukraine just can’t prevail even with our new materiel. That seems to be a sincere belief which he backs up with a whole lot of arguments. Do you think he’s just been manipulated or do you think he’s just wrong?

APPLEBAUM: So, I don’t know exactly what J.D. Vance’s goals are or why he’s doing what he’s doing. But he does — he himself manipulates facts. I mean, for example, he talks about Russian — the Russian ammunition outnumbering the amount of ammunition Ukrainians have is five to one, you know, that happened because we stopped giving the Ukrainians ammunition. In other words, you know, he’s — he uses this narrative of inevitable defeat by, you know, citing the fact that, you know, using the fact that we weren’t helping them. So, you know, the Ukrainians themselves, you know, are redoing their system of recruitment, they are retraining their soldiers, and they’ve proven that they can evict Russians from Ukrainian territory that they occupy. They have already pushed the Russians out of — 50 percent of the territory that was occupied at the very beginning of the war. So, they’ve shown they can achieve things. And for Vance to say, it can’t be done, and therefore, we might as well give up, is genuinely giving in. It’s first of all, giving into Russian propaganda. And it’s also — you know, it also fails to account for how the Ukrainians will fight and how the war will progress once we are helping them. So, yes, of course, if we’re not helping them, then loss is much more likely. But if we are helping them, then we can turn it around. And so, by Vance, you know, saying that they’ll lose, you know, because we won’t help them and therefore, they’ll lose is, it’s not a very honest argument.

ISAACSON: You wrote a wonderful book in 2020, it’s a seminal book about our time, which is called “The Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism.” And it explains why contemporary countries, and even some in the West, have been weak in defending the old-fashioned liberal ideals of democracy. Do you feel that Ukraine is the frontline of that fight? And if so, do you see — how do you see this fight going over the next decade?

APPLEBAUM: So, I do think that Ukraine is the front line in the international, the geopolitical aspect of that fight. We are now living in a world in which Russia is allied with Iran, China, Venezuela, Belarus, and other autocracies. They have, you know, different goals and different kinds of political systems, but they do see themselves as aligned against democracy and particularly against the language of democracy, human rights, rule of law, transparency, because those ideas, which are often the ideas used by their own internal opposition would be threatening to their form of dictatorship. And one of the reasons why Russia invaded Ukraine was because Putin wanted to show Europeans, in particular, that he doesn’t care about their — you know, we don’t change borders by force, rules or their laws on human rights or their language, you know, never again, we mustn’t allow mass murder to happen in Europe again after the Second World War. He wanted to show Europeans he doesn’t care. And he can kidnap thousands of Ukrainian children, which he has done, and he’s been sentenced by the International Criminal Court for doing so. He can put Ukrainians in concentration camps. He can, you know, randomly murder Ukrainians walking down the street in occupied Ukraine. If we really care about those ideas, if we believe that you shouldn’t be able to occupy other countries and destroy them and change their identity and murder their people with impunity, then yes, we — this — Ukraine in that sense is the front line in a broader war, whether it continues further militarily into Poland, in the Baltic states, whether it continues further into Africa, where there’s a large Russian presence already, whether it means — just means that Russia is emboldened to use its, you know, information warfare and propaganda in new ways all over the world that this place to stop them.

ISAACSON: Anne Applebaum, as always, thank you so much for joining the show.

APPLEBAUM: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

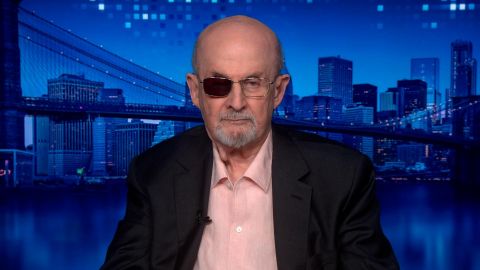

UK Shadow Foreign Secretary David Lammy is encouraging “progressive realism” as Britain increases its defense spending in the midst of increased conflict across the globe. Author Salman Rushdie addresses the 2022 stabbing attack that almost took his life in his new book “Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder.” The Atlantic’s Anne Applebaum on why Ukraine must defeat Russia.

LEARN MORE