Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: Hello everyone and welcome to Amanpour. Here’s what’s coming up.

The latest dump of Epstein emails still making waves. We discuss the revelations with Chief National Affairs Correspondent Jeff Zeleny.

Then, what Zohran Mamdani’s win as Mayor of New York tells us about a larger worldwide trend in left-wing politics. The leader of the U.K.’s

progressive Green Party, Zack Polanski, joins me to discuss countering the right and his own surge in the polls.

Plus, “Waiting for Godot.” Samuel Beckett’s legendary play is back on Broadway. And I speak to its stars, Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter, about

taking on this absurdist masterpiece.

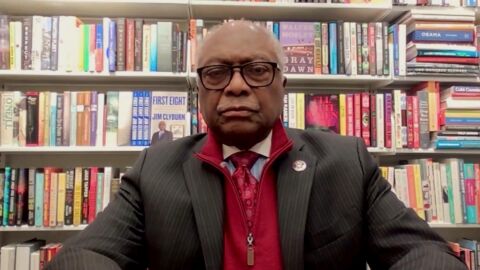

Also, ahead, African-American trailblazers. Congressman Jim Clyburn talks to Hari Sreenivasan about his new book profiling the eight black political

pioneers who came before him.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

And we begin with more revelations from the Epstein files. Thousands of emails to and from Jeffrey Epstein have been released by the House

Oversight Committee, exposing a web of connections to the disgraced businessman and convicted sex offender who was found dead in his jail cell

in 2019.

Of course, all anybody wants to know is about President Donald Trump. While the White House says there’s nothing to see here, the Democrats were first

to release a handful of emails where Epstein discussed him. Trump admits they were once friendly, but says he cut ties with him years ago. The

Republicans responded by releasing the full set of emails and documents, a whopping 20,000 of them, that they had obtained from the Epstein estate

through a subpoena. And now, with the House finally back in session after a long-drawn-out shutdown, lawmakers could force the release of even more

documents.

So, to discuss all of this, let’s bring in Jeff Zeleny, who’s following the story closely from Washington. And, Jeff, thank you for being with us. It’s

obviously having ramifications over here in the U.K. as well, for obvious reasons. So, just wondering what led to this and what kind of waves is it

making in Washington now?

JEFF ZELENY, CHIEF U.S. NATIONAL AFFAIRS CORRESPONDENT: Well, Christiane, it’s making considerable waves. And you could see just by how

the White House was scrambling really in the last day to respond to just a wave of emails. And what these emails have done really have revived the

conversation that revolves around a very simple question, what did Donald Trump know about what Jeffrey Epstein conduct was at the time, long before

Donald Trump was president? Of course, he was on a celebrity apprentice. He was a he was a celebrity at the time.

However, these emails that were released on Wednesday, as you said, first from House Democrats to really shine a light on the fact that the president

may have known more about the activities and conduct of Jeffrey Epstein than he has suggested up until now. That was followed, as you said, by

House Republicans releasing just a deluge of documents, some 20,000 pages of emails.

So, you get the sense that they want to bury Washington and so many emails. It’s kind of hard to follow what is actually going on. But when we’ve

looked through those and we are still looking through all of them, we have learned a few things. And one is Jeffrey Epstein said quite bluntly that

Donald Trump had spent hours at his home, more than we had previously learned. And the question is why. The answer to that was certainly not

forthcoming by the White House. The White House has repeatedly tried to say the president has done nothing wrong. But a bigger question is, did the

president know about Jeffrey Epstein’s wrongdoing?

So, all of these emails really shine a light on a variety of people from Larry Summers, the former treasury secretary and head of Harvard

University. He, of course, is a Democrat. He had a close relationship with Jeffrey Epstein. He was asking him for relationship advice. It also shines

a light on a variety of other figures talking about Epstein.

But again, focusing on the matter at hand here, that is the president. And the White House went to great lengths yesterday to try and move beyond

this. But that clearly is not possible. And much more will be coming out and being learned about this in the coming days.

AMANPOUR: So, Jeff, what happens next? Everybody is pointed to finally the speaker of the House seating the Democratic congresswoman from Arizona

after keeping her essentially away from taking her seat for many, many weeks. What does this actually mean in this case?

ZELENY: So, what this means in this case is that was the 218th vote. So, that meant the House now has enough votes, enough support to essentially go

over the rules of the speaker. It’s called a discharge petition and have a full vote of the House. So, Speaker Mike Johnson on Wednesday evening

finally agreed after not agreeing for months and months. Finally, the House next week will vote on the full release, urging the Justice Department to

fully release all of the Epstein files, the case files.

That doesn’t mean it’s going to happen. Of course, the Senate would have to vote on it. That is unlikely. But what this means is that House Republicans

now will have to take a stand vote on this. And the White House has mounted a massive pressure campaign trying to not even allow it to get to this

step.

Something happened yesterday in the Situation Room of the White House that was quite extraordinary. This is the fifth American president I’ve covered.

Never can I recall a White House Situation Room meeting on a matter like this, not of national security. But the attorney general of the United

States, the deputy attorney general, the FBI director all summoned one member of Congress, Lauren Boebert from Colorado, a Republican who had been

sort of on the fence. She’s obviously very supportive of Trump, but she also wants transparency in this case. She did not give in to the pressure.

She signed this discharge a petition. So, now the full vote will be next week.

But I am told there is a full pressure campaign from the White House to try and not let there be a wave of House Republicans voting to release these

files, because the White House is trying to not allow that to happen.

Again, the bottom line here, what did the president know about Jeffrey Epstein’s conduct? And if it was nothing, why are they going to such great

lengths here to try and stop this? Again, we should say the president has not been accused or charged of any wrongdoing. This is a friendship from

long ago that he, like many other famous people at the time, had a relationship with Epstein and many people, including his own supporters who

started all of this, who talked about releasing all these files. And the president, as he was running for president during his campaign last year,

he agreed to release the files.

Of course, now he’s in power. He has not agreed to it. So, that is, in a nutshell, why this has become an issue for the White House.

AMANPOUR: And just finally, you talked about Representative Boebert who was taken into the Situation Room over this. What is the situation with

those MAGA Republicans? Is it causing a fissure or are they sort of kind of over it and talking about other issues? And would they, I don’t know, work

with Democrats to bring this to, you know, a complete vote to release all these things?

ZELENY: Christiane, that’s been so interesting about this. The politics are a bit upside down of what they used to be. Democrats used to really not

talk about this at all. This was a MAGA issue, if you will, issue important to the president’s base. Now, that the president is in power, it’s flipped

somewhat.

But for some of those House Republicans, they still believe that transparency is the most important effort here. Nancy Mace from South

Carolina, Lauren Boebert from Colorado, Thomas Massie from Kentucky, all Republicans are leading the charge that they say these files should be

released. So, it’s not as toxic or front of mind in the MAGA world, if you will, among some. But among many, sort of others, they want there to be

transparency here.

So, it’s hard to imagine this really ever going away and the president moving beyond this until there is more known about this. And, again, the

simple question is, why not release the files? The president campaigned on that. His supporters wanted it at the time. And now, suddenly he’s calling

it a hoax. But we have heard that word before. And usually when President Trump is calling something a hoax, there is more to the story than that.

So, we’ll see what that House vote happens next week. And, Christiane, my eye is on how many Republicans are going to vote really against the wishes

of the White House and vote to release the full files of the Department of Justice.

AMANPOUR: Jeff Zeleny, thank you very much for bringing us up to date. Now, meantime, also in the United States, New York’s mayor-elect is getting

ready to lead the city after his historic win. Zohran Mamdani’s unprecedented campaign captivated people not just in America but also

around the world. His relentless focus on affordability and his effective social media messaging galvanized younger voters in particular.

The Democratic Socialist is part of a larger movement of left-wing politicians now trying to take on the right. It’s a tactic being employed

here in the U.K. also by the Green Party. And Zack Polanski just took over as their new leader. And since then, the party has surged in the polls and

membership has doubled.

Reacting to Mamdani’s win, Polanski declared hope has triumphed over hate. And he’s joining me here now in the studio. Welcome to the program.

ZACK POLANSKI, LEADER, THE GREEN PARTY OF ENGLAND WALES: Thanks so much for having me.

AMANPOUR: Yes. With all of this conversation and this division that we see in the United States, and the pylon, which you remember well about Mamdani

at the beginning from those who were opposed to his candidacy in the establishment, do you think this is a moment where something other than

right-wing populist nationalism, left-wing populism, I don’t know, is making a stand, can make a stand?

POLANSKI: I think it absolutely needs to be otherwise our planet is under threat and people who really need an alternative, some of our poorest

communities around the world, are under threat too.

I think, first of all, it’s important to define the word populism. So, as I see it, it’s the 99 percent versus the 1 percent. The 1 percent being

multimillionaires and billionaires, elites who have taken our power, our wealth, and our assets. And I believe it’s time to take them back.

Now, the 99 percent is an incredibly unifying message because actually that’s about working-class people, small business owners, medium business

owners, disabled people, people who aren’t in work, everyone who has so much more in common than a tiny, small elite who are often — journalism is

a hugely noble profession. There are journalists dying around the world to report in conflict zones. However, there is a section of journalism,

particularly I would say in the U.K., that has given over to right-wing tropes, where the multimillionaires and billionaires who often donate to

the politicians also own those organizations. And they’ve relentlessly attacked me here in the U.K., and we’ve seen this with Zohran in the U.S.

But where I get hope from is Zohran has demonstrated that hope can triumph in the end.

AMANPOUR: And you have actually spoken about the similarities you feel with him in terms of his campaigning tactics, in terms of his strategy. I’m

really interested in how you’re defining terms. You call yourself, I believe, an eco-populist, right?

Zohran Mamdani has called himself a democratic socialist. Everybody wants to call him just a socialist, and some even go so far as saying communist,

you know. How do you think he can get over that naming that people are using to undermine him, saying that he’s against the American way? And I

mean, we know that socialism is an actual thing where the state captures much of the production capabilities, and that’s not what he’s talking

about.

POLANSKI: Well, I think the way he can do it is by lowering people’s bills and giving universal free childcare and affordable rents. And I think

people aren’t worried about the labels. They’re worried about what are you delivering for them. And the reason why I talk about eco-populism is that

is the idea that if you’re worried about the food on your table, the heat in your homes, then the climate crisis can feel a very distant threat.

Now, we know that the climate crisis will hit the people who have done the least to cause it the hardest. It’s going to hit working class communities.

However, if you’re someone who’s struggling just to get through the day, then it’s very difficult to start as an entry point. And I think what

Zohran’s really demonstrated is to rise above these labels. Parts of the media can talk all they want about him. Actually, he’s getting out there

and speaking to grassroots communities.

AMANPOUR: And quite a diverse constituency, given the massive margin of his victory.

POLANSKI: Massively so. And I think the big thing that people get wrong with him is there’s a kind of obsessive focus on his social media and his

communication style. Now, don’t get me wrong. His social media is excellent, and I’ve certainly modeled myself on it.

AMANPOUR: Yes, I was going to ask you about it.

POLANSKI: And his communication, he’s an exceptional communicator. You really feel what he’s transmitting, and it just comes off completely

authentic. However, I think the most important thing is the message he’s actually saying, which is a message about inequality and affordability.

Because if you have great social media, but you don’t have a good message, you’re just exposing the nothingness and the vapidity that we have with so

many modern politicians. If you have a great message, but you don’t have the communication style, no one’s going to hear you. And what he’s done is

combine both, and that’s the winning combination.

AMANPOUR: So, you explain you then now to us, because as I let in, you’re the latest or the newest leader of the Green Party, and its membership has

doubled and you’re surging in the polls. You’ve got four seats in Parliament. That’s not a lot, given what the other bigger parties have.

You’re not likely to be prime minister anytime soon. But how do you explain your rise?

POLANSKI: I mean, it’s been a phenomenal moment for the Green Party and a really exciting moment for the country. Since I’ve got elected, we’ve

doubled our membership. Today there was a second poll out where we were above the Labour government in second place. So, that’s an incredible rise

very, very quickly.

Now, polls, members, they don’t ultimately mean anything unless you win seats. So, I accept the challenge. I want to make sure at the next election

we are mobilizing to win seats.

There’s been a lot of focus about the fact that 18- to 24-year-olds are joining the Green Party in huge droves. And that’s amazing. I’m excited and

inspired by the younger generation. I should say, though, every time I go on TV and say this, I get so many messages from people who are over 50 and

say, don’t forget about us. We have joined the Green Party, too. And actually, we are sick of the old party politics. We’re very, very worried

about Nigel Farage on the right and the rise of division and hatred. And actually, they’re really excited by the politics of hope, community and a

politics that says, let’s lower our bills and let’s tax billionaires. I think that’s a message that works with lots of diverse coalitions.

AMANPOUR: So, obviously, a lot of other people just hate it when they hear about a wealth tax and people say it’s going to drive the — you know, the

wealth makers away. It’s going to suffer the economy and jobs and all the rest of it. But I’m really interested in what you say about you might have

ideas, but if you don’t have a message, it’s not going to work.

Certainly, the right and you can see with MAGA, you can see with Brexit and even reform, they have a very clear message. It’s very disciplined. It’s

about immigration. It’s about, you know, the economy. It’s about essentially also fear. And it appears that the left-wing has not had such a

clear message to actually go head-to-head. Do you think that’s changing?

POLANSKI: Yes, it’s something I’ve been thinking about a long time. I think if you’re on the right, there are very powerful communicators on the

right and you have to give credit.

AMANPOUR: Yes, they really are.

POLANSKI: But very often, I would say they are not based in information. In fact, they’re based in misinformation and they have powerful stories

that emotionally connect. And that’s how they change people’s minds.

On the left, I would argue for a long time, across the world for left to get very involved with data and spreadsheets. And that’s really important.

You’ve got to start with science and research and be factual in what you’re talking about. But if you stay there and you don’t also have an emotive

story, then people get pulled in by the fear every single time.

Hope is an incredibly powerful emotion, but it needs to be hope combined with delivery and a whole suite of policies that are going to change

people’s material living conditions. I believe that’s what we’ve got on the left now in the U.K. with the Green Party of England Wales. But I’m also

seeing it right across the world. We see it with Zohran. We see it with Claudia in Mexico. We see it with lots of socialists or left-wing

progressives around the world. And we are starting to win.

AMANPOUR: And do you count in there the centrists who won against the far- right in the Netherlands?

POLANSKI: Well, I mean, anyone who defeats the far-right is someone, you know, that’s a celebration I have. I do ultimately worry, though, that

centrism or this idea that a wealth tax won’t work. If people kind of buy into those ideas, I do worry that they might hold power for a few years.

But if you don’t change people’s living conditions, something even worse than the previous far-right will turn up and we just keep going into this

spiral.

And I think that’s a lesson Keir Starmer really needs to learn right now. He went on a message of change in the U.K., but actually not a lot has

changed. We had 14 years of conservative underinvestment. Labour have continued that same program. And so, what he’s doing is he’s handing this

country on a plate to Nigel Farage.

And even if he stops him temporarily, something worse than Nigel Farage will turn up. And that’s why I think it’s really important we win these

arguments on wealth tax, because, again, coming back to the research and science, all of it shows that an unequal society is bad for everyone,

including multimillionaires and billionaires. And a fairer, more equal society is actually good for everyone, including the super-rich, because a

happier, healthier society is good for everyone’s well-being.

AMANPOUR: That’s one way of putting it. On climate, which is your thing, I mean, the Green Party, you know that President Trump has taken a view about

climate change, the climate crisis. He’s called it a hoax. I just want to play to remind everybody what he said about climate at the U.N. this past

September.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DONALD TRUMP, U.S. PRESIDENT: It’s climate change, because if it goes higher or lower, whatever the hell happens, there’s climate change. It’s

the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world, in my opinion. Climate change, no matter what happens, you’re involved in that. No more global

warming, no more global cooling.

All of these predictions made by the United Nations and many others, often for bad reasons, were wrong. They were made by stupid people that have cost

their country’s fortunes and given those same countries no chance for success. If you don’t get away from this green scam, your country is going

to fail.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, I want your reaction to that, but also in terms of not just the moral cause of climate and the planet, but also the economic

opportunity to lift a nation’s economy by going into this new green technology.

You know, I had Vice President Al Gore on the show yesterday, and he said, why doesn’t anybody talk about the subsidies all governments give to the

fossil fuel industry, for instance?

POLANSKI: Absolutely. I think your question is so well put, because if we remove those subsidies to fossil fuel companies, we could be using that

same money to invest in what’s known as the just transition. And all I mean, by that is investing in the new industries and renewables and solar

and wind and making sure that if people are going to lose their jobs, that we make sure they’ve got different jobs to go into.

Now, the best time to do this would have been a decade or two ago, it hasn’t been done, we can’t re-litigate history, but what we can do working

with the trade unions and workers is making sure that we put those workers at the heart of those plans right now so they can co-design what that

future looks like.

In terms of Donald Trump, look I’m a politician so I always want to be as diplomatic as possible, but it’s very difficult to call him anything but a

fool. This is a man who is — this is sociopathic behavior. He’s selling our children and our grandchildren down the river for a profit. He is the

very epitome of someone who is knee-deep and sky-high invested interests with fossil fuel companies, who will say anything that is convenient to him

at any moment, who is science denying, who is toxic, who is misogynistic and racist. And I think it’s pretty clear that I’m not a huge fan of Donald

Trump.

AMANPOUR: It’s pretty clear. I want to ask you a personal question finally. Mamdani made waves being the first Muslim mayor of New York City,

you’re Jewish, your family changed the name to Paulden to avoid antisemitism, you changed it back to Polanski. It’s a major problem,

antisemitism, around and in politics and it appears in domestic politics, it was a big part of the New York City race. How do you navigate that as an

issue?

POLANSKI: I think I always make sure that I center people who are experiencing racism every day or indeed this often gets conflated with the

genocide in Gaza and to make sure that I center the plight of the Palestinians.

In terms of my personal experience, I do suffer lots of antisemitism online, but actually, I find that I just stay focused as I do with any hate

and actually go what am I in politics for? I’m in it to empower people, to work with grassroots communities and actually it’s not about me at all.

I think the work I’m most proud of though is when I work with people like my Muslim deputy leader, Mothin Ali in the Green Party. I think that’s a

very powerful message to have a Jewish leader and a Muslim deputy leader because we both recognize that antisemitism and Islamophobia are two sides

of the same coin and the best response to hatred is solidarity.

AMANPOUR: That’s a hopeful note. Zack Polanski, thank you very much indeed.

POLANSKI: Thanks so much for having me.

AMANPOUR: Now, to Broadway and the revival of a masterpiece. Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” was first performed in the 1950s, but decades

later the surreal tragicomedy continues to captivate theater goers. And this time a star-studded cast is grabbing their attention. Hollywood actors

Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter. The “Bill and Ted” film co-stars reunite on stage as the central characters Vladimir and Estragon. And they’re joining

me now from the Hudson Theater in Manhattan. Welcome to the program.

KEANU REEVES, ACTOR, “WAITING FOR GODOT”: Hello.

AMANPOUR: Hi.

ALEX WINTER, ACTOR, “WAITING FOR GODOT”: Thank you for having us.

AMANPOUR: It’s a great pleasure. Now, I — should we just put the pronunciation to bed. I call it Godot. What do you call it?

WINTER: Godot.

AMANPOUR: Keanu?

REEVES: Godot.

AMANPOUR: All right. I’m not going to ask you why —

REEVES: But we understand. I mean.

AMANPOUR: Go ahead.

REEVES: No, no. I mean, it’s — it comes inherently with the play, right?

AMANPOUR: Yes.

REEVES: You know, North America if you read it, you know, oftentimes it’s Godot. When you play the part, when you play — do the play from other

performers in the past connected to Beckett and otherwise —

WINTER: Yes.

REEVES: — it’s Godot. And there’s many elements in the play that suggests that — in the performing of the play the pronunciation Godot works much

better with the text.

AMANPOUR: All right. Now, I think people who’ve never read the play or seen the play always knows the title “Waiting for Godot” has become a —

you know, a common parlance in everyday life. But for someone who’s never seen how would you describe this play?

WINTER: I mean, it is a play about two very close and old friends who are trapped in an indeterminate location in an indeterminate time who are

trying to find a reason to live and survive. And it’s a play that interrogates sort of the questions of meaning and life and spirituality and

friendship and many, many other things.

REEVES: And it’s a comedy.

WINTER: And it’s a tragedy.

REEVES: It’s a tragic comedy.

WINTER: It is indeed.

AMANPOUR: I feel like letting you carry on because it’s a good performance right here. But listen, you talk about a friendship and obviously the

origin story is “Bill and Ted” kind of do Beckett. Casting you as Vladimir and Estragon either makes perfect sense or no sense. Whose idea was it to

bring you together to play? And how — seriously, how did it get to Broadway?

REEVES: That was my brilliant idea. And about three and a half years ago I rang up Alex and said, hey, do you want to do this play? And you said —

WINTER: I do.

REEVES: And then he said we need a director. And I guess, you know, Jamie Lloyd. And we went on — we invited him to meet and we met in New York

City. And yes.

WINTER: So, we had time. We’ve had several years to do the work on the play. We both knew it was a monumental thing to do. We both have done

theater and are very big fans of Beckett, and we wanted to sort of bite off this thing. And Jamie Lloyd has had done a ton of work with Pinter and has

done a great job of bringing classics into the modern era as well as doing modern plays. So, it was a good fit. It proved to be a very good fit

thankfully.

AMANPOUR: Well, look, I’m going to play a little snippet. We’ve been given a few little clips. So, I’m going to play a little bit. And then I want to

get to — you just say it, it took a long time to study up and to prepare to do this.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WINTER: You must have had a vision?

REEVES: What?

WINTER: You must have had a vision?

REEVES: No need to shout. Do you?

WINTER: Do you? Oh pardon.

REEVES: Carry on.

WINTER: No, no, after you.

REEVES: No, no, you first.

WINTER: I interrupted you.

REEVES: On the contrary.

WINTER: Ceremonious ape.

REEVES: Punctilious pig.

WINTER: Finish your phrase I tell you.

REEVES: Finish your own.

WINTER: Moron.

REEVES: That’s the idea. Let’s abuse each other.

WINTER: Moron.

REEVES: Vermin.

WINTER: Abortion.

REEVES: Morphine.

WINTER: Sewer rat.

REEVES: Curate.

WINTER: Cretin.

REEVES: Critic.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, it’s all getting big laughs from the audience. But what does the scene tell us about your relationship? Well at least the

relationship between Vladimir and Estragon. Who are they to each other?

REEVES: Well, there’s love, companionship.

WINTER: History.

REEVES: History.

WINTER: And, you know, sense of surviving together and being together too long. Fear of mortality, I think. I’m afraid of your health and you’re

afraid of mine. And, you know, we’re refugees. I think it’s sort of quite clear. We’ve — the things that the text gives you is there is a refugee

component to who we are in the world that we live in. We have performed together. That’s in the text. And those —

REEVES: But I think you’re a philosopher and I’m kind of nature. You know what I mean? Like being in philosophy. I think that there’s a kind of side

— two sides of a coin of the way of being. The points of view.

WINTER: Yes. You’re rooted to the earth and my head is sort of up there.

REEVES: Yes.

WINTER: Yes. Literally.

AMANPOUR: You know, you’ve just — you know, actually, you just acted out right now something I read in the research that Jamie Lloyd, the director,

when you were practicing and reading he talked about Alex looking with love and fun fondness as Reeves performs a scene at Babo (ph), and I thought

that was really a cool thing for a director to take from you two friends and his two stars.

How does your long — what — tell me about that? How difficult was it to get this right and how did the friendship and the love that you had for

each other help?

WINTER: Well, the friendship helps in a number of ways, not the least of which we trust each other and we have a performing bond and a friendship

bond, and the play is about friends, so we can use that in the play, but it also means that embarking on this very intense journey together meant we

were doing it with someone who you knew you liked and got along with and would be laughing during the times when you want to cry and —

REEVES: Crying with laughter.

WINTER: That’s right. So, there’s a lot to it, frankly, that both informs the play and also just makes the process itself easier.

AMANPOUR: Was it difficult? I mean, I think Samuel Beckett is kind of intimidating just to read and try to figure him out and not to mention

playing this iconic play. You came to Reading I think, you went to the library, you searched for months and months through the archives. And as

you say, it took a long time. How difficult, involved, intense was the practice before you even got to the theater?

REEVES: And fun.

AMANPOUR: And fun, of course.

REEVES: And fun.

AMANPOUR: And fun.

WINTER: Yes.

REEVES: I mean, it’s extraordinary to do that research, right? And the artists that we spoke to, the archivists, the biographer of Beckett, actors

who have performed it.

WINTER: People who knew Beckett who had worked with him as actors and colleagues. Yes, it was very, very rewarding. We had a — it was a really –

– we were lucky. In this business it’s rare that you have years to work on something. And obviously, we were doing other things at the same time, but

we really took the time to dive into this.

But at the end of the day, you kind of have to throw that stuff away on some of it, it ends up in your system, so you’re not discarding it all. But

you really have to do the play itself. And so, that helped us when we got to day one of rehearsal with Jamie, we had this nice bedrock of stuff that

just was underneath everything else when we just went off and started playing Vladimir and Estragon.

REEVES: And I think part of that too is the grounded approach that you and I took from the very beginning of trying to ground the play, ground the

characters in a way, you know?

WINTER: Yes. Yes, to make them feel like two actual human beings and not like absurdist archetypes, which can happen sometimes in the production of

this play.

REEVES: Nothing to be done.

AMANPOUR: We have a nice big shot of your — you know, the theater. In fact, we’re looking at right now. And behind you is that tunnel which was

clear in the clip that we played, because you’re in that tunnel. I want to know what that represents, but I love this comment from one of the critics.

It was as if you were circling the drain of life waiting for a fatal flush, that’s “Waiting for Godot” and Vladimir and Estragon. So, I just found that

really visual. But tell me about the stage —

REEVES: I guess they didn’t like the play.

AMANPOUR: No, they said a lot of other good things. I just thought it was very descriptive. But what about that tunnel?

REEVES: It is. I mean, we love —

AMANPOUR: I mean, it’s kind of unusual.

REEVES: I guess there’s the practical side of performing in it, but I think also just the symbolic prompt, this symbolic invitation of trying to

— you know, you were speaking about the creative pause, you know, the — you know and sharing that idea and the quote of that, but the pause of like

contemplating what is it how does it — what does it mean to you, how does it affect — what does it make you think of — one think of, you know.

WINTER: Yes. Yes, it creates ambiguity, but for an actor it actually creates specific parameters that are quite constrained and those are useful

because these are these are two characters who are trapped in time, they’re trapped with each other, they’re trapped with their thoughts and the

audience is trapped. And it creates a kind of a literal trap.

REEVES: And a foci, right?

WINTER: Yes.

REEVES: It made us be very specific —

WINTER: Yes.

REEVES: — in a way.

WINTER: And it’s also a stage which Jamie is leaning into and it also looks somewhat like a vaudeville clamshell. And there we are the bowler

hats and we play air guitar and we’re two characters who have done physical comedy together just as the characters in the play have, and there’s a kind

of a vaudeville proscenium aspect to it as well. So, it’s a very clever design. I’m very taken by what they came up with.

AMANPOUR: So, you just mentioned air guitar, that’s, I assume, a deliberate reference back-to-back to “Bill and Ted.” I don’t know. How did

that come up? Does the audience recognize it?

WINTER: Oh, yes. Oh, yes, they recognize it.

AMANPOUR: And do they love it?

REEVES: Not everyone, but some people.

AMANPOUR: I might not have done. I might not have done. I’ve seen —

REEVES: Well, it’s a wonderful gesture. You might not.

AMANPOUR: I’m going to play a little clip.

REEVES: You have to watch that on a rainy Sunday.

AMANPOUR: Exactly. Well, now, I’m going to play a little clip of “Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure” from the original trailer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WINTER: How’s it going, royal ugly dudes?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Put them in the iron maiden.

WINTER AND REEVES: Excellent.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Execute them.

WINTER AND REEVES: Bogus. How’s it going, dude?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): Blow them up.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

Oh, yes.

AMANPOUR: I mean, hugely popular. Not an obvious leap, not an obvious connection from there to where you are right now. How does that —

WINTER: Ted hair?

REEVES: You do?

AMANPOUR: You still? OK, you still. So, it is an obvious connection. But listen, I want to ask you something, because you’ve twice said, Alex, that

this is about refugees. You are refugees. And as you know, certainly in your country and certainly in — you know, in the West right now, refugees

are demonized, they’re, you know, deported, they’re shut out.

And I was really interested to know that Samuel Beckett wrote this play originally in France. He himself fought in the resistance with his French

wife. He was incredibly lucky to escape with his life from the Nazis. I mean, it’s a really profound origin story. It’s really incredible to read

the backstory of it. And I just wondered how that resonates with you today, performing this in New York right now.

WINTER: You know, Keanu and I have talked about this quite a bit. And we’ve talked to a lot of people who have seen the play or produced the play

at times of great strife or civic unrest or war. And we’re very happy that this play doesn’t specifically kind of bracket the times that we’re in,

which we feel would diminish the scope of the play.

But of course, it speaks to autocracy and fascism and state violence and surveillance. I mean, this stuff is in the text. So, you can’t not feel it.

And I think whenever the play is put on, especially when the times are fraught, which — and let’s face it, most times are fraught for someone.

It’s going to be felt quite deeply in that way. And so, of course, we feel that. Of course, we do.

REEVES: We’ve lost our rights.

WINTER: We got rid of them. It’s right there in the text.

AMANPOUR: I was in Sarajevo in ’93 when Susan Sontag put on “Waiting for Godot” in Sarajevo, under siege by the Bosnian Serb forces. And she said

then it was her way of pitching in or doing something tangible. Do you feel at all like that in doing this now, Keanu? I don’t know. Is there

something? It’s such a famous play and it has so much meaning, even though it’s kind of meaningless.

REEVES: You know, myself and Alex and Michael Patrick Thornton and Brandon Dearden, the four of us, Vladimir, Estragon, Lucky, Pozzo, we huddle up

before each performance. And often part of that huddling up is speaking about the audience and the reactions that each of us are getting

individually from people, friends, family, from strangers about their experience of watching the play.

And, you know, it’s — I was crying. I was laughing. I don’t know what’s going on. It’s —

WINTER: I’ve seen the play four times and I get something different from it every time I see it. Yes.

REEVES: And so, this kind of feedback is worthwhile. It’s why — and we speak about why are we here? What are we doing? And the relationship

between the play, us performing it and the audience. And there seems to be a wonderful exchange.

WINTER: Yes. And I don’t think so much — and I know this isn’t really what you’re saying, but I don’t think so much of acting as activism. I

mean, I think what Sontag was doing with that play was specific at a specific — in a specific value. But I think for us, I wouldn’t say what

we’re doing is activism. I mean, some of us are doing activism right now and it’s not this.

But there is something about theater that is undeniably powerful in the interchange between humans and what that does.

REEVES: Life activism.

WINTER: It is and it does activate people. And it activates us, too, though. We are prone to that as well as the audience. We’re not immune to

that and we’re not — it’s not dogmatic. We are not presenting that to them. We are part of that exchange. And that is what I love about theater

so much.

AMANPOUR: Yes. Well, wish we could talk more. Congratulations to both of you. Keanu Reeves, Alex Winters, thank you so much for joining us.

AMANPOUR: Now, since coming into office, the Trump administration has been waging a war on DEI, calling into question the hard work of many who shaped

the United States. Take one American cemetery, World War II cemetery in the Netherlands, where a display once commemorated the black soldiers tasked

with burying thousands of American troops. But in March, that display was taken down by a federal commission on grounds of, quote, “interpretive

content.”

Now, in the face of acts like these, Congressman Jim Clyburn has written a new book profiling the pioneering black politicians of South Carolina to

whom he attributes his own career success.

Clyburn was the first African-American to represent South Carolina since 1897, and his book, “The First Eight,” focuses on the trailblazing black

lawmakers from his own state. He’s speaking to Hari Sreenivasan about the parallels between the battle for democracy in the past and present.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN, INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT: Christiane, thanks. Representative Jim Clyburn, thanks so much for joining us. This is not a

traditional political memoir. You chose to turn to history, to the eight black congressmen who were elected to represent South Carolina before you,

and you also weaved in some of your personal reflections. Why take this route?

REP. JAMES CLYBURN (D-SC), AUTHOR, “WAITING FOR GODOT”: Well, I thought about these eight people for a long, long time. My father, when I was a

youngster, made me learn everything about Robert Smalls. I knew that Robert Smalls was born enslaved, that he had escaped slavery and had become a

member of the state legislature and of Congress, and I didn’t know a whole lot about the others. But my dad insisted that every day after we finished

doing homework, we had to share with him a current event. So, I got involved and interested in politics at a very early age.

And so, right after I wrote my regular memoir, I received visitors in my office one day, and one of them asked me about these eight pictures up on

my wall. When I explained who they were, one of them said to me, I thought you were the first. And I kind of playfully said, no, before I was first,

there were eight. And I decided that day that maybe I would make my next book about these eight people.

And I started really working on it leisurely. And then, the 2020 election happened, and I started seeing what was going on up in Michigan,

Pennsylvania, down in Georgia, trying to develop these alternative electors for the presidential election. And I recognized from these people’s lives

what was going on. We were trying to get the next president certified, and the former president, or the president who had just lost, was then trying

to get that certification nullified, exactly what led to the demise of the careers of these eight people.

And so, I changed direction, started the book over, and decided to focus on tying their experiences to what we’re experiencing now. And quite frankly,

the parallels are very eerie.

SREENIVASAN: I want to talk about the parallels, but I also want to introduce our audience to a couple of these characters that you write

about. Let’s start with Robert Small, who you discussed briefly. You say, by my estimation, Robert Smalls is the only bona fide Civil War hero of the

eight, and one of only two blacks to serve as a delegate to the 1868 and 1895 constitutional conventions, which granted, then revoked, black

political and civil rights in the state lived the most consequential life of any South Carolinian in your memory.

I mean, that is already consequential in itself, what you just described. But how did he get to that position? How did he escape?

CLYBURN: Well, it’s the most remarkable event, I think, in the entire Civil War. Robert Smalls was born enslaved. Mother got very concerned about

him and his safety living in slavery. So, she talked her owner, John McGee, into letting Robert Smalls go to Charleston to work. And all the income, of

course, would go to the owner.

And one day, while working on the waterfront, he had achieved some degree of some elevation among his peers. He was passing around the ship one day

and playfully threw on the captain’s hat. And one of his brothers said to him, you look remarkably like the captain under that hat. And that gave her

an idea.

And Robert Smalls started planning an escape using the people he worked with on the ship and his family. And they successfully absconded the prize

ship of the Confederate Army, which was the planter. And they sailed that planter into freedom.

He then started serving in the Navy and became the first captain of a naval ship. The first African-American captain in the Navy. So, I tell young

people all the time, as my dad used to tell me, there’s nothing new under the sun. So, we start talking about all these firsts today. Robert Smalls,

to me, was the first and maybe the only real hero of the Civil War. The first black captain in that war served 10 years in the South Carolina

legislature. And after that, served ten years in the United States Congress. All of that wrapped up in one person.

Now, he escaped in May — in August of that year. Robert Smalls was in Washington, D.C. to try to convince Lincoln, President Lincoln, to allow

blacks to serve in that war. Because they were forbidden. He convinced Lincoln. And Lincoln authorized him to go back to South Carolina, recruit

5,000 black soldiers, which later became 40,000. And Abraham Lincoln himself said, but for those 40,000 soldiers and others after them, that war

would have been lost by the Union.

SREENIVASAN: You write in the book, faith is a through line in American history, particularly in the black community. Who was Richard Cain? Why

does he stand out? Why does he resonate so personally for you?

CLYBURN: Richard Cain was a native of West Virginia. His family moved to Ohio. And he felt a call to the ministry and was educated at Wilberforce

University, the first private HBCU. But he became disenchanted with the Methodist church that he was a pastor in. So, he left that Methodist

church, became an AME. And then he was sent to — here to New York. And he became the pastor of Bridge Street AME Church over in Brooklyn, New York.

But he tried to volunteer for the Union Army. And he and several others were turned down because they were not allowing blacks to serve. And very

explicitly said to blacks that this was a white man’s war. And we have stipulated in the book this having been said. But he never gave up on it.

And when the war was over, he was sent to Charleston by the AME movement to rebuild Emanuel AME Church, which had been destroyed over the attempts by

African-Americans to escape. 1822, the church was burned down because of Denmark Vesey. 30-some-odd people were hanged. And, of course, he was so

successful at rebuilding that church.

They couldn’t hold all the people. So, he started a second church, Morris Brown AME Church, which I became a member of. And he was the first pastor

- But he did something that I warn people about today. He used his relationship with the church. He bought a newspaper that he published. And

between the church and that newspaper, he built a political dynasty in South Carolina and became a very astute member of Congress and was a

founder of a HBCU down in Texas and became the 14th bishop of the AME Church.

SREENIVASAN: Given the election results just recently, do you think that the Democrats made a mistake in striking a deal, or at least the number of

Democrats who crossed over to try to end the government shutdown made a mistake?

CLYBURN: You know, no, I don’t. I’m not going to vote for this bill simply because it does not go where I think it should go. But I don’t think it was

a mistake. I think that what we have to do is balance interests here. We got the SNAP benefits. The problem with SNAP, we got that addressed. We got

the problems with the women, infants, and children addressed. There are significant things that did get addressed in this deal. But everybody is

focused on the one thing we didn’t get.

You know, Lyndon Johnson — I should never forget, when we were passing civil rights laws back in 1960, and when we passed the Civil Rights Act of

1964, in order to get the act passed, they took voting out of it and they took housing out of it. And then it passed dealing only with employment. A

lot of people got angry about that. And Lyndon Johnson famously said, a half loaf is better than no loaf. So, let’s apply that to this. We may have

gotten a half loaf, but that’s better than no loaf.

SREENIVASAN: Congressman, finally, you know, you close out your book with the state motto of South Carolina, while I breathe, I hope. And I wonder,

what is it that gives you this eternal optimism, considering that you’ve literally been on the front lines of so many times where people would give

up? What spurs that sense of purpose and kind of maybe mission in the morning when you say we can still make something better? Because there’s a

lot of people who are kind of looking for that hope.

CLYBURN: Well, you know, I remember questioning my dad about just what you’re talking about. I had a real problem. My father was a fundamentalist

minister. I questioned a lot about what he was preaching and what I was living. And I never shall forget one day he said to me, son, the darkest

point of the night is that moment just before dawn. And that has so much meaning to me, and it still has.

I know how dark it may seem, but we could very well be in that moment just before dawn. So, you don’t give up on the process. You keep pressing

forward. And so, I say to young people all the time, Robert Smalls did not give up. When Robert Smalls got to Congress. Robert Smalls was indicted on

trumped-up charges and was put in jail. And it was awful relief if he would just get out of politics. He refused. He refused.

And so, I say to young people, no matter how dark it is today, no matter how difficult the task may be, you can’t give up on the process, especially

if you’ve got children and you’ve got grandchildren. So, you’re going to quit. Then what’s going to be their future? So, if they don’t have a

future, it must not be because you didn’t do your darnedest to make sure that they have.

SREENIVASAN: Representative Jim Clyburn from South Carolina, also the author of “The First Eight,” thanks so much for your time.

CLYBURN: Thank you very much for having me.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Powerful stuff. And that’s it for now. Thank you for watching. Goodbye from London.

END