Cranks Creek, Kentucky

Cranks is an unincorporated community in the southeast of Harlan County, Kentucky, near the Virginia state line. Harlan County was immortalized in a documentary about a miner’s strike that took place there in 1973. Though a bargain was struck, the mining jobs have dwindled ever since. Today, 30 percent of the county lives below the poverty line. The last memories of good mining jobs are now a generation away, but Cranks is lucky to have engaged community members who have set up resources like the Cranks Creek Survival Center, created after a flash flood in the 70s swept away people’s houses in the area. Photojournalist John Lowenstein visited recently to document lives of people living there.

Danny Stewart, 30

Stewart is a fifth-generation miner who started working in the mines shortly after graduating from high school in 2004. The pay was good and he used to be able to find work easily, but work has been far less regular since President Obama won re-election in 2012, he claims. He says they’re “just barely getting by.” Although Stewart admits he doesn’t follow politics closely, he hopes that Donald Trump will win November’s presidential election and improve life.

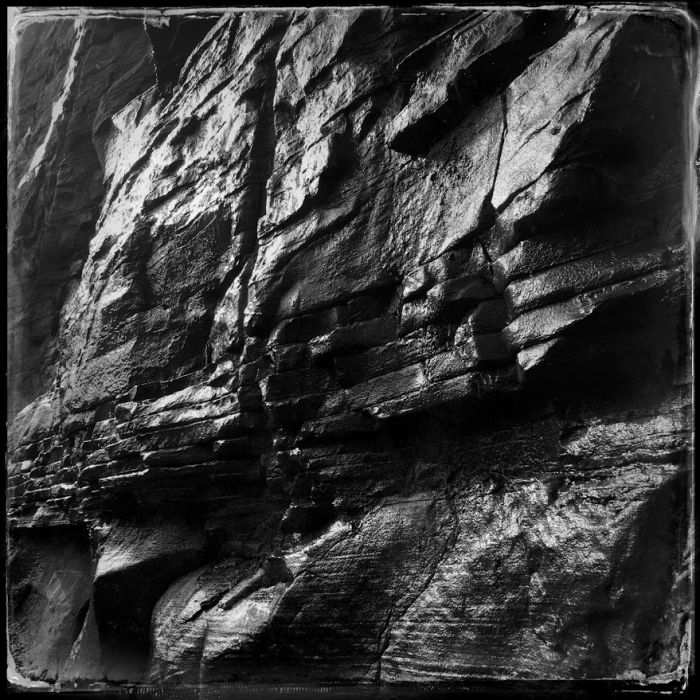

Seams of coal on the side of the road on Route 421 in Harlan County, Kentucky

The Appalachian mountains contain hundreds of millions of tons of coal wedged in their seams. This inky substance has been the lifeblood of the region’s economy for generations. But the number of mining jobs has dropped steeply in the past 30 years, forcing many young people to leave the area they love, and those that stay into poverty.

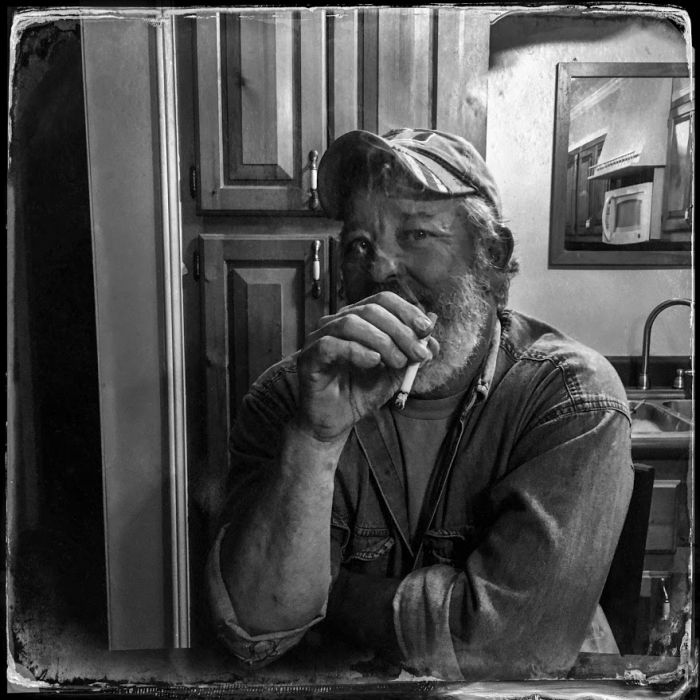

Robert Simpson, 57

Simpson mined for a dozen years in the 1980s and 1990s before becoming a carpenter. He is part of a family that has worked at mines for four generations: his grandfather, Charlie; his father, Bobby; and his son, Brandon, all put up years in the mines. He and his wife Judy live on a plot of land off of Route 568 in tiny Cranks. Judy, who recently moved from part-time to full-time status at Walmart, says that life is “good for the moment."

Students from DePaul University work on building a new porch at the home of Levi and Luwonna Burkhart in Coldiron, Kentucky

The students were participating in an alternative Spring Break program and were one of thousands of groups that have come to the area to work on homes and bring food and clothing through the Cranks Creek Survival Center. The Center was created in the late 1970s after a flash flood caused by strip mining destroyed the area.

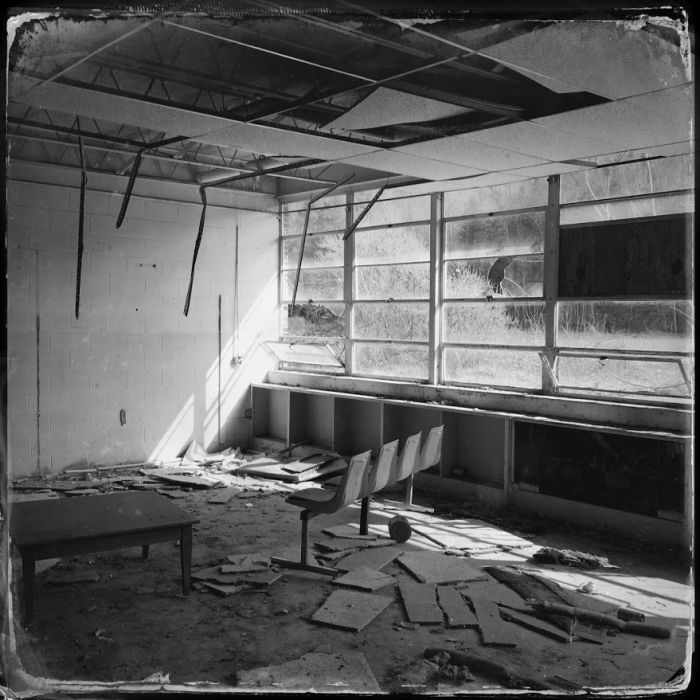

A room in the former elementary school in Cranks Creek, Kentucky

Shuttered in the 1990s due to declining enrollment, the school shows no signs of reopening as the county’s population has continued to drop due to the loss of coal mining jobs. Light industry and manufacturing options have been touted since the time of the school’s closure as a replacement for the industry, but they have not materialized. Many in the area blame President Obama’s “War on Coal,” but the industry was in decline decades before the president assumed office in 2008.

Charles Napier, 70s

Chester Napier grew up in the 1940s in a one-room log house in the woods of Smith, Kentucky. His father, Fred, taught him how to hunt animals like groundhog and deer. The family of eight children didn’t have much money, but Chester did not consider himself poor. He said that the battery in his pacemaker has three years left and he’ll decide then whether he wants to have a new one installed. But he knows where he wants to be when his life ends. “I’m home where I want to die at in these mountains here,” he said.

Chester Napier walks along the road in Cranks Creek

As a young man, Napier moved north from Appalachia to Chicago for a dozen years, returning home after a child of his died after living for just 3 days. Napier has been in Harlan County ever since. In the 1970s, a strip mining company forced him to sell land he owned by asserting its ownership over the property’s mineral rights. He still misses his wife Annie, who died about a decade ago

The waters of Cranks Creek, Kentucky

The banks of the creek were overrun with muck and debris following flash floods caused by strip mining in the late 1970s.

The late Becky Simpson pulled her children to safety in the nearby mountains and watched as everything they and other families owned washed away. She organized 17 families to file the first successful class action suit against strip mining companies, and lobbied vigorously at the state and federal levels to secure money from the government to dredge the creek and protect residents.

Bobby Simpson walks with the assistance of Jeff Kelly Lowenstein, a writer and investigative reporter

Simpson, 79, has been blind since the early 1960s, but gets along so well that some people have known him for years and not realized that he has a disability. Along with his late wife, Becky Simpson, Bobby started the Cranks Creek Survival Center after flash floods devastated the community. Kelly Lowenstein came to the Center for the first time in the late 1980s and spent a weekend putting insulation in a home with other volunteers. He has continued to visit the area ever since.

Becky and Bobby Simpson shortly before she passed away in 2013

The couple founded the Cranks Creek Survival Center after a 1977 flood washed away their home and devastated their community. For almost forty years they have fought to help the fellow residents of Harlan County, Kentucky.