Former Chaplain at Cook Country Jail Exposes the Harsh Realities of Mass Incarceration

TRANSCRIPT:

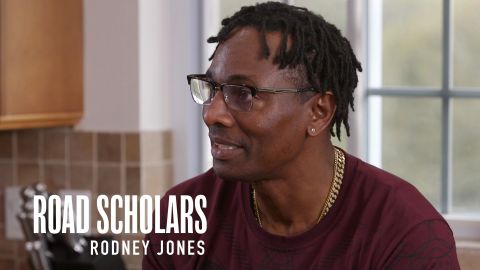

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, the criminal justice system is something our next guest understands all too well as well. Reuben Miller is a former chaplain at the Cook County Jail in Chicago. He is also a sociologist, criminologist and a social worker. His new book, “Halfway Home,” exposes the realities of life after under mass — after mass incarceration and shows that some people are never truly free even after they leave prison. Here he is talking to our Michel Martin about the book and his own personal experiences with America’s prison system.

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Thanks, Christiane. Professor Rueben Miller, thank you so much for speaking with us.

REUBEN MILLER, AUTHOR, “HALFWAY HOME”: I’m so glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

MARTIN: You know, the whole topic of mass incarceration, the criminal justice system in general is a very big topic right now. But you’re focusing on the long tail of incarceration. What happens when you supposedly get out? How did you start to notice that this was a story in itself?

MILLER: I began this work as a volunteer chaplain at the Cook County Jail in Chicago. And so, it was really getting close to these men. It was really looking from the ground not necessarily from the 30 or 40,000 feet in the air where we tend to look at these questions where we’re counting things. You know, can you get a job or not? How many people are unable to get a job? What is the unemployment rate? No, no. What I found was that — people’s fundamental relationship to things like the labor market was different or are you able to reconnect with your family? That is very important. But what I found was, when sitting across the kitchen table, those relationships and those conversations look fundamentally different for these folks than they do for other people.

MARTIN: Why is that?

MILLER: Because we’ve created a pariah class in this country. Because we’ve inaugurated an alternate form of citizenship for people with criminal records. Because there are 45,000 laws, policies and administrative sanctions that target people when they get out of jail or prison that prevent them from getting work or housing. And these things cause real strain in their relationships.

MARTIN: I think what I hear you saying is people are still locked up even if they’re not locked up.

MILLER: That is absolutely right. What I decided to study was what I called the afterlife of mass incarceration. And so, this is the way that prison follows people. It’s like a ghost. It shows up at their job. It shows up in their relationship between even their most — their intimate partners. It shows up when they’re trying to rent an apartment. It follows them. It traps them. People are imprisoned effectively in their home communities. But what is worse is the informal stuff. So, there is the — you can’t get a job. You can’t get a house because of the laws and policies that we’ve passed but there’s how that shows up in their everyday lives and their everyday relationships with everyone else they encounter.

MARTIN: And forgive me, Professor Miller, but I think this is where I think it would make sense to say this is also your problem. I mean, this is also part of your life as well. Why don’t you tell me a little about your story? In fact, you write about your story eyesight story quite a lot in the book. Your father was incarcerated, has been, and so is your brother. How did that — tell me about that.

MILLER: Yes. You know, so my grandmother raised us. And we were in foster care. She took us in. And when my brother initially got in trouble, he was sent like many children who are in the foster care system to group homes. And from there trouble escalated. So, once marked by the criminal justice system people begin to pay attention to you in a very different way. And for me, while I was arrested at 14 and, you know, it’s in the book, I was arrested because I was trying to do graffiti in trainyard. I’m not that good at graffiti. But that arrest didn’t follow me in quite the same way in part because of the arbitrary nature of enforcement that we see happen in the criminal justice system. So, what happens in poor black communities, and I was raised in a poor black neighborhood in Chicago, what happens in poor black communities is on the one hand there is over policing and on the other hand there is under policing. There is over policing but under policing and under protection. And so, you know that you can be arrested. You know that you might get in trouble. You don’t know what that trouble looks like. And once you are convicted, though, once something happens that leads to a conviction, that conviction begins to follow you and those many arrests that you may have had growing up coming up as a child are then used against you when you become an adult. And so, my brother’s experience escalated from there. So, when he became an adult and got into trouble, he had a record, that record was used against him. He was sent to prison. And so, that is a part of my story. The reason why I write about that is because it occurred to me that if I was being honest that I would have been in my own social scientific model. I was born poor and black after 1972 where mass incarceration begins in earnest and I grew up in a residentially segregated neighborhood. I, like every other black American man in this country and many black American women, wouldn’t have been able to avoid prison if I tried.

MARTIN: Why do you say that?

MILLER: The prison follows you.

MARTIN: Talk more about that because I think a lot of people have this idea that you have to do — A, you have to do something serious to get locked up.

MILLER: Yes.

MARTIN: And, B, you do your time and if you keep your nose clean as it were and then that’s done. And what you’re saying is that is just not true. Just walk me through that.

MILLER: I’ll give you an example from the book. There is a man named Martin who has experienced serial traumatic episodes, all kinds of traumatic violations. He was the victim of sexual abuse. He was the victim of physical abuse and domestic abuse from his parents. You know, these things happened. The police were not there. There was no one there when he called for help, when he asked for help. No one there. No program there to meet Martin and help Martin figure out what was going on with him. Martin becomes homeless. Martin is arrested 14 times not for some giant violent offense. He is arrested 14 times for trespassing. All of which were misdemeanor offenses. Martin turns to drugs and alcohol. A friend of his dies. Too much trauma. Too few people to turn to to help him process it. Well, he is arrested for having three crack rocks in his pocket. He is charged with a felony conviction. Why? The judge says, he thinks that’s excessive. The prosecutor says, well, his 14 arrests prove a pattern of criminality. And so, what happens? On average, my guys were arrested 15 times on average, the guys that I follow. I follow 250 guys out of American jails and prisons in Chicago, Detroit, New York, and other smaller towns across the country. They were arrested 15 times on average, most of which beginning at the age of about 14 years old, most of that for doing things that kids do every day. And so, by the time they actually got in trouble, and when I say doing things kids do every day, I mean things like hanging out together, standing on a corner, congregating in groups, you know, these kinds of things. And when they finally get in actual trouble, those early police interventions are used to prove that they are indeed criminal. This is because black people in this country are stripped of their innocence. They’re viewed as already guilty even as children.

MARTIN: You are being very delicate about Martin’s story. I found it deeply disturbing. And Martin was raped multiple times as a child.

MILLER: Yes.

MARTIN: And as a young man. And never seems to have gotten any care for what he experienced. And then when he started self-medicating in part to deal with the trauma, he was punished for that. So, I guess what I’m asking you is, do you think that even as a child you thought, you looked around and think — thought, why?

MILLER: No. No. Because it was so normal for so many of our friends to be arrested and incarcerated. No because the model interaction, the everyday, the most frequent interaction that someone from my neighborhood had with the police was being arrested. It wasn’t officer friendly or something like that. So much so that kids made games of it. OK. Here are the cops. Let’s run. Right? So, it’s like — and this, too, is the — what I call the afterlife of mass incarceration. The presumption of innocence that is stripped from black children. The presumption of guilt that’s dropped on black kids all over the country. The fact that police only show up to arrest you. That they don’t show up when you call. They don’t show up when Martin needed someone to show up for him, for many black children. And the literature says that. We believe black children are four years older on average and more guilty when we see them. This is how Tamir Rice can be murdered within two second of a cop getting out of the car. And the only question that we ask is whether or not the cop felt safe. This is how we get to that point. It is the presumption of guilt that is foisted on to black children, even black children in this country.

MARTIN: You also talk a lot about the long tail of financial burden that attaches to being incarcerated. And that is something that has a ripple effect on any family member outside that may want to stay connected to you. Talk about that.

MILLER: That is absolutely right. When I was doing my research in Detroit, this is during the time that my brother got arrested in the Michigan Department of Corrections, the average cost of a phone call for me to talk to him, because they only allow you to talk for 15-minute blocks, was $6.55. That was the average cost per phone call. That was after a series of reforms to reduce the cost. And so, $6.55 per call in an era of cell phones where phone calls are effectively free if you pay your average bill. Families have been shown to go bankrupt covering things like the cost of phone calls. But there —

MARTIN: Well, let’s talk about this for a second. You’re saying the average cost of a phone call was $6.53, if the federal minimum wage is $7 an hour.

MILLER: Come on.

MARTIN: If someone is paying — is working a minimum wage job making that federal minimum wage essentially an hour’s worth of their labor —

MILLER: Goes into that phone call.

MARTIN: — goes into talking to their loved one.

MILLER: That is absolutely right. That’s absolutely right.

MARTIN: And why does it cost so much? It doesn’t cost $7 to make a phone call. So, what is that about?

MILLER: Well, it’s about contracting with private services. When people talk about prison privatization, they often think about only private prisons, that this is where typically the imagination of what privatization looks like in prisons. But everything is privatized in prisons. So, look at this obligation for a second. The family pays for the phone call, something that’s effectively free if you pay a monthly service for any other person in the United States under any other circumstance. The family pays for food because the prison doesn’t cover the actual needs of the people inside. The family covers the cost of confinement in some states. They get a bill. This is what you need to pay because your loved one was incarcerated and we’re going to charge you for that. The family covers the cost of legal fees, $1,600 for general legal fees. My brother was charged $600 for representation by a public defender that he met for 20 minutes on the day of his conviction. The only meeting with the public defender. All of these costs are borne by the family. For someone who the state has effectively made unable to care for themselves. That is on the inside. Now, on the outside. They’re locked out of the labor market. They can’t get a job. There’s rules that say they can’t rent an apartment. It’s legal to discriminate against people with criminal records and to deny them leases and to even evict them from homes if a — for example, let’s say a grandchild stay on the couch. So, they can’t find a place to stay. They can’t support themselves. They can’t get a job. Who is going to cover their bills when they get out? The family. And so, it is not just the millions of people who are incarcerated or even the 19.6 million people who are estimated to have a felony record, it’s everybody who is connected to them. They’re all brought into their punishment. This is what mass incarceration has done.

MARTIN: Can you just read a little bit from the book that I think sort of captures it? I think you could pick something for us.

MILLER: This is from chapter 4, a chapter called “Millions of Details” and it’s after I’m having a phone call with my brother and the passage goes, any boxer will tell you that it’s the punch you don’t see coming that puts you down, the collect call you didn’t expect, the court date you didn’t have the gas money to attend, the conversations you’ve dreaded having with your children about why their uncle was in prison and when exactly you expected him to come home. The honest answer? You’re not sure. The $2.95 processing fee that brings your bills above your budget. The $292 that you’ve over drawn your account. The six $34 over draft fees because you didn’t budget the last collect call. The overpriced boots. The unexpected embarrassment as you sit at your desk entering your loved ones order 30 packages of ramen noodles. What it feels like when Michigan packages runs out of the flavor of ramen noodles you wanted. The fact that you know or at least you think you know that no one else is in your shoes if these little things, the daily disruptions that manage to pull you down. Shame does that, too.

MARTIN: Why shame?

MILLER: There’s an interesting association between the arrest and the presumption that it is because of something that you did. Because of this connection that we’ve made in the American imagination between crime and punishment. So, Americans look at the 2.3 million people who are in a U.S. jail or prison and they look at the fact that 40 percent of them are black. And then we say to those, and then say, it must be because of something that black people do. Despite the fact there have been 2,800 exonerations since 1989. Despite the fact 95 percent of those cases are resolved in a plea deal, but these are things that we don’t know because we don’t pay attention to these folks. These are folks that we’ve labeled guilty from birth. And so, because of that, because of the deep connection between what we presume to be behavior and punishment you must have got coming what you called for. One of the guys in my study said, I got what my hand called for. That’s what he said. In fact, people who would be in jail or prison, when I would visit with them, who were convicted of crimes they didn’t commit, said, well, I wasn’t convicted for the crime that I did but I certainly did something that made me deserve to be here. This is the kind of language that we circulate in. And so, a sense of guilt and a sense of shame, embarrassment because of this terrible person that you must be follows you. And the second part of the shame comes from the fact that incarceration separates families. It pulls apart, it isolates, it makes it so that you feel alone. And when you’re alone there is very little you can do. You feel powerless. You feel as if you can’t control the forces that are shaping your life. And for that, you feel a sense of shame.

MARTIN: Does that follow you when you get out?

MILLER: Everything in the world tells men that men are to be the providers and protectors of their home, but there are 19,000 laws, policies and administrative sanctions that tell them that there are hundreds of categories for employment for which they may not apply and the jobs are unsustainable when they have them. So, it is nearly impossible to get a job. The jobs you do get are often the worst kinds of jobs. And then when the boss disrespects you at work because there are so few things that you can do, there’s so few ways you can move, you can’t leave the job and go try to get a new one. And so, what we’ve done is we effectively pushed this group of folks out of the labor market and told them that their identity is defined by their ability to make money. This is part and parcel of how shame follows people with criminal records, but it does this in housing, it does this when it comes to civic participation. Not just voting, but which offices you can hold. It does this when it tells you, you can’t sit on a jury. So, every time you go before a “jury of your peers,” there is nobody in that jury box that has had your experience, nobody in the jury box that quite understands who you are and what you have experienced or even how you changed your life after you’ve gotten out of prison. Nobody understands that. And you know that. You know effectively that you’re alone.

MARTIN: What would make a difference? What would make a difference in your view?

MILLER: I’d talk about mass incarceration as a problem citizenship, and I say that for a couple reasons. Reason one is there are unique laws, policies and sanctions that target just them and the unique responsibilities just for people with criminal records and their rights are suspended in many forms and ways. That is the kind of legal sense in which it’s a kind of citizenship. But there is also a social sense in that citizenship, at the end of the day, is really about belonging. It is about belonging to a political community. It’s about being a fully human participant within a community of other humans that has a place in the social world just because you’re a human being and you are part of our collective. I think this is the kind of thinking we have to take to this problem. And if we started there from this framework, this framework of belonging, from a framework of human thriving, what does the person who caused the crime need to thrive? What does the person who’s had the crime committed against them, the person who’s been harmed, what do they need to thrive? If we start from this place of human thriving, we’ll start doing very different things. For example, there are 45,000 laws. We don’t need 45,000 laws. In the State of Illinois there are 50 housing regulations. In the State of Illinois. One state, 50. We don’t need 50. The second is to ask when should punishment stop? When has one paid their debt to society as to have an actual reckoning with our system of punishment. To ask questions we haven’t really asked. We’ve been operating on muscle memory for the last, I don’t know, 50 or so years. And I think we can do something for it.

MARTIN: Professor Miller, thank you so much for talking with us today.

MILLER: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me.