While Morocco’s Atlas Region Recovers From a Devastating Earthquake, Another Crisis Threatens To Eradicate a Way of Life

By Marlowe Starling, Rana Morsy and Rishabh R. Jain with Brahim Alae and Kira Kay

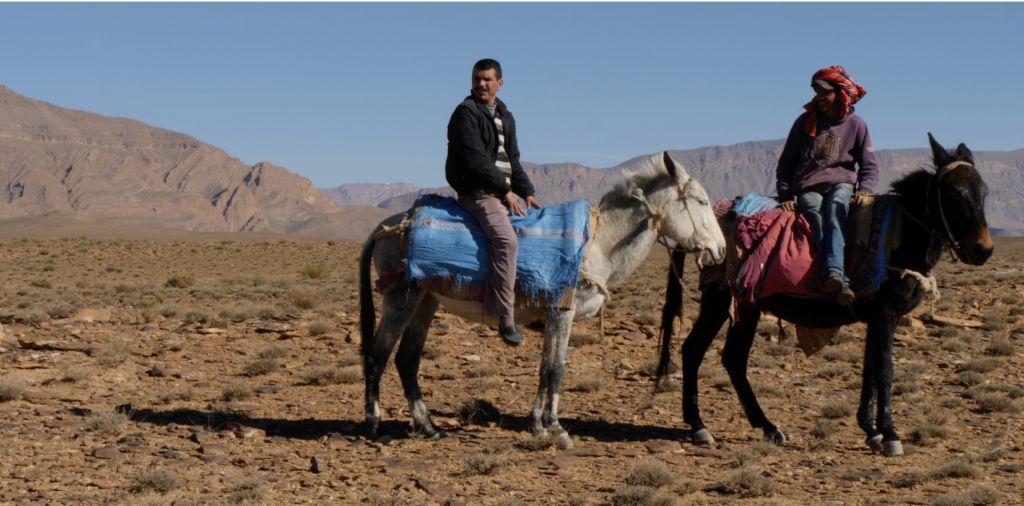

Driss Skounti stands in a field of rocky gravel, gazing pensively at the mountains that surround him. “In February, when it snowed, we originally thought it was a mercy. We thought it was great. Now the snow’s only visible on the mountains, as if it never snowed at all here, as if nothing happened. Everything’s dried up.”

He says that while the wells and some small springs were refilled, the fleeting snowfall had no impact on the region’s vegetation. And for Driss Skounti’s community of Amazigh nomads – who traditionally spend their winters in the valley floor to graze their flock and then migrate into the mountains when the summer heat descends – the lack of vegetation could mean life or death for their animals and their traditional culture.

Driss Skounti says the word Amazigh means “free people.” But the Amazigh are more commonly known as Berbers. This Greek and Roman term for foreigners, derived from the Greek “barbaros” or barbarian, is not used by the Amazigh themselves.

The ancestral lands of the Amazigh include the Drâa-Tafilalet – the stunning desert and oasis region bordering Algeria that includes the High Atlas Mountains. A 2014 census in Morocco showed only 25,000 nomads remaining in their ancestral lands. The number represents a 60% drop from the census a decade before, and Skounti believes next year’s census could see the numbers halve again, indicating as few as 12,000 truly nomadic Amazigh people remaining in Morocco.

When Morocco embraced an Arab identity at its independence in the 1950s, the Amazigh were marginalized politically and socially. Also, their language was not allowed in schools. More recently, Morocco has begun to recognize the deep national origins of Amazigh culture, granting official recognition of the Amazigh language, as well as the Amazigh New Year, Yennayer – now a national holiday.

Still, the Drâa-Tafilalet remains underdeveloped. And now, says Driss Skounti, four years of drought are plunging the nomads further into poverty. With less livestock to sell at the market, basic staples like flour, sugar and vegetables have become unaffordable. Families in search of jobs, health care, and education for their children have little choice but to give up their nomadic traditions and move to urban centers. The nomadic community around the town of Assoul – where Driss Skounti’s grandfather settled on land near a local spring in the 1930s – once numbered 650 family tents. Now the number has dwindled to 83 as families move further afield to seek water and grazing land – or abandon their pastoral livelihood and move to cities in search of new lives.

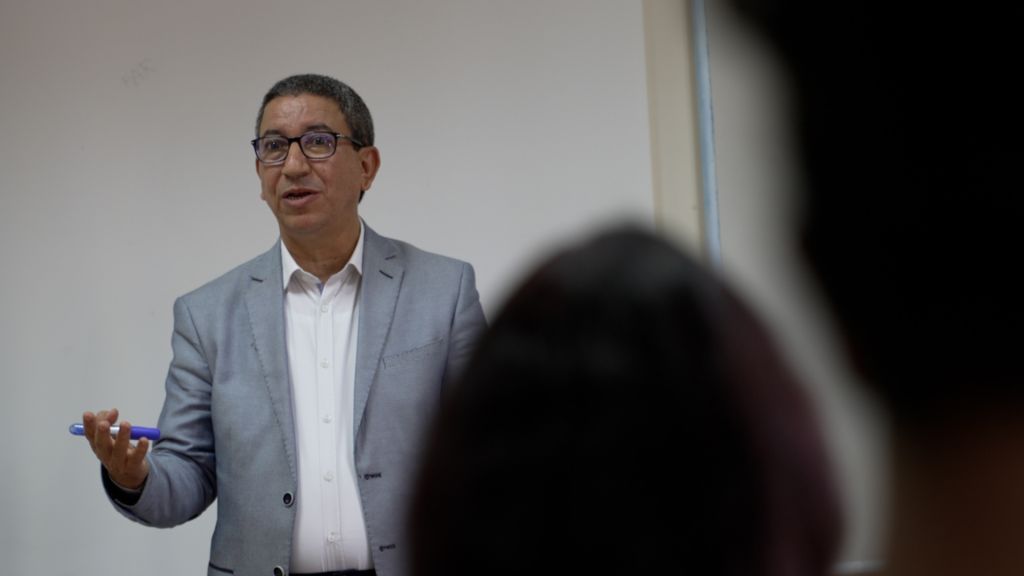

More than 300 miles away, another Amazigh nomad worries about the future of his community: Dr. Ahmed Skounti – Driss’s brother – who works as an anthropologist at the National Institute of Archaeological and Heritage Sciences in Rabat, the country’s capital. He knows well the dynamics of the exodus of nomads from the Drâa-Tafilalet. As a young child, Dr. Skounti himself traveled away from the region with an older brother in pursuit of educational opportunities.

Dr. Skounti has also witnessed environmental change. Morocco, like other countries in North Africa, faces increasing desertification. Rains are both less frequent and more severe, leading to a long-term decline in vegetation. This in turn increases soil erosion and creates conditions that can lead to dangerous flash flooding. The World Bank’s climate projections predict more frequent and severe droughts in the central and southern parts of Morocco, where Amazigh communities live.

Morocco’s remote communities are suffering the effects of a climate crisis caused by others. The disparity in carbon emissions between more and less developed countries is clear: Rich countries pollute far more by metric ton than poorer ones. The entire African continent contributes less than 4% of global carbon emissions, while the world’s top emitters — China, the U.S. and the E.U.— collectively contribute more than half.

Despite this inequity, Morocco has taken a very public stance on its climate and renewable energy goals. The government says it will exceed its Paris Agreement commitment for reducing carbon emissions by more than 45% by 2030, and has begun wide-scale construction of desalination plants, green hydrogen generators, as well as wind and solar power projects — many funded by the country’s government-owned, multibillion-dollar phosphate mining company, OCP.

Morocco even has a national “Green Mosque” program that helps places of worship to install solar panels and other low-carbon technology. The program also trains Imams, Mourchidates and other religious and societal leaders to include environmental messaging in their public outreach.

Meanwhile, coal is still a major source of energy in Morocco, and plans are in place to expand the country’s fossil fuel infrastructure, according to a detailed report from Climate Action Tracker.

Driss Skounti agrees that the government’s ambitious climate plan has yet to impact his Drâa-Tafilalet region. His brother, Dr. Ahmed Skounti, adds that industrial farming of the oasis region’s signature date palms is deepening the drought crisis by further depleting the already struggling underground aquifer that supplies the region with fresh water for consumption and irrigation.

The Moroccan government is providing direct aid to nomads, including subsidizing food staples and animal feed to the extent of one-third the price. It is also installing solar-powered water pumps on wells in the region, allowing communities to reach deeper into the aquifer for drinking water – though not enough to address the lack of vegetation for their grazing animals.

Driss Skounti has created an independent organization to assist the government in administering these programs, help his community navigate the system, and fill in the gaps when government aid falls short. His brother, Dr. Skounti, is part of a Moroccan government task force working to come up with a 25-year development and land use plan for the desert region. Dr. Skounti also advocates on a global stage, acting as an adviser to UNESCO, the U.N.’s cultural heritage agency, and speaking at climate conferences about the connection between cultural and environmental preservation.

Dr. Skounti also believes that the region’s tourism business – offering travelers the opportunity to ride a camel and glamp for a night or two under the stars – should be managed by locals, rather than by tour operators that drop in from Morocco’s popular destination city, Marrakech. Economic development is central to his task force work.

And so the brothers fight on – much as their grandfather did against the French during Morocco’s struggle for independence – defending a mountaintop not far from where Driss works today. Both men are doing what they can, in their different ways, to preserve their Amazigh culture and nomadic way of life for future generations.

This article and accompanying video were reported by a group from New York University’s international field reporting class GlobalBeat, a joint project of NYU Journalism and the Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies. The team included Marlowe Starling, a graduate student at NYU’s Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program, Rana Morsy, a Moroccan-American graduate student in Near Eastern Studies, traveling to Morocco for the first time as a journalist, and Rishabh R. Jain, a member of the News and Documentary program at NYU and a videojournalist for the Associated Press, based in India. Brahim Alae and Kira Kay assisted with their reporting. Thanks to the Luce/ACLS program in Religion, Journalism and International Affairs and the Marc Haas Foundation for their support of GlobalBeat.