Public records requests create challenges for North Carolina’s election system, workers

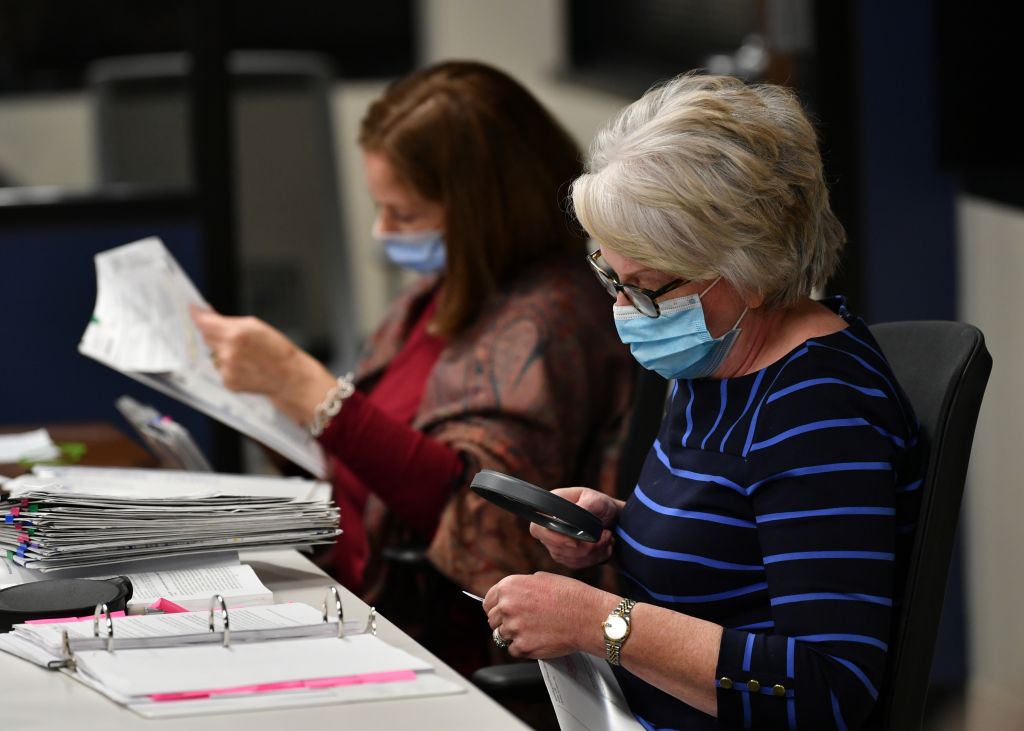

The sheer volume of paperwork created by a few ‘election integrity’ activists is straining election administrators’ resources

On Nov. 30, 2022 — 757 days after the 2020 general election — a team of four “election integrity” activists entered a room in Dobson, North Carolina, and pulled out their cell phones. They were seeking answers from the Board of Elections for Surry County, a rural area home to about 71,000 people on the state’s northern border.

Supervised by a bipartisan team of poll workers specially hired for the occasion, the activists laid out page after page of printouts from Surry County’s voting machines on long tables. For the rest of the day, the four slowly scanned their phone cameras over the poll tapes. They scrutinized the evidence for manipulation in an election that had been certified over two years before, in a county that former President Donald Trump won by over 51 percentage points.

“It was the most tedious — I can only imagine, had I been the person that had been directed to come and sit and look at that, that I would have pulled what little hair is on top of my head out,” said board member Clark Comer at a subsequent meeting.

What Comer observed was the end of a much longer journey for Michella Huff, Surry County’s director of elections. In response to concerns over the 2020 election, she and her staff had to keep the poll tapes for months after state law allowed them to be destroyed, spending over $600 for an auxiliary storage unit. While still undertaking all the regular preparations for the 2022 midterms, her team had to spend 135 hours getting the old documents ready for inspection.

Prior to 2020, elections offices like Huff’s used to operate mostly under the radar. But following unfounded allegations of fraud promoted by figures like Trump and MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell, voting administrators across North Carolina and elsewhere have found themselves under unprecedented levels of scrutiny, particularly in the form of extensive public records requests.

Pat Gannon, a spokesperson for the North Carolina State Board of Elections, estimates that the state received roughly 50-100 elections-related records requests per year prior to 2020 — few enough that officials didn’t bother to track them. That changed after the last presidential election: 2021 saw 229 requests, and last year brought 330.

Similar trends are in play at the local level. A recent Votebeat investigation found that requests to elections administrators in Wake County, home to the state capitol of Raleigh, went from just over 50 in 2020 to 171 in 2022. Corinne Duncan, who runs elections for Buncombe County in western North Carolina, says requests to her staff have roughly quadrupled over the same period while also becoming larger in scope.

Duncan emphasizes that transparency is critical to maintaining public confidence in elections and that people have a right to inspect many parts of the process. But increases in records requests, many arriving as form letters generated by statewide or national groups, have placed a new burden on her office’s day-to-day work.

“We used to be able to take these six months [after the midterm election] and really focus on preparing for 2024 without doing so much overtime,” she says. “We have to have time where we are recovering.”

That’s a common theme among officials across the country, says David Becker. He directs the Washington-based Center for Election Innovation & Research, which supports U.S. voting administrators and works to build public confidence in the electoral process.

Becker believes that the way records requests are employed by some groups brings challenges beyond the logistics of their fulfillment. What he calls the “grifter-industrial complex” of election deniers, he says, often uses obscure voting documents to fuel disinformation.

He points to a request made in Oregon for a contract between the state and KNOWiNK, an elections technology vendor. Based on a misreading of a clause that allowed manual data entry in some cases, election deniers proceeded to falsely claim that the vendor’s software would allow Oregon officials to manipulate final vote totals.

“Most of these people don’t understand what they’re actually looking at,” Becker says. “Since none of this stuff actually indicates fraud and is clear that fraud did not occur, it causes many of those asking for this information to spread disinformation about what these documents say to fit their narrative.”

The very prospect of being targeted by a bad-faith public records request, Becker adds, can discourage elections officials from building networks of support. Because records requests can include messages, such as emails and texts, made to further government activities, some administrators have started communicating less over the last three years.

“It was very common for election officials to meet across state and party lines, to engage with researchers like my organization and others to discuss what best practices might apply,” he says. “Now they’re isolating themselves for fear that someone might potentially misinterpret an invitation or a meeting that they attended as some kind of conspiracy.”

Neither Keith Senter, chair of the Surry County GOP and lead organizer of the poll tape request, nor fellow requester Carol Snow responded to multiple messages seeking comment. But Preserving Democracy did speak with Jim Womack, president of the North Carolina Election Integrity Team, which since February of 2022 has worked to file requests across 80 of the state’s 100 counties.

The group’s intent isn’t to harass voting officials, Womack says, but instead to ensure accountability at a time of deep distrust. He points to a June survey by Rasmussen Reports finding that over half of likely U.S. voters believe cheating will sway the results of the 2024 election.

Womack claims that public records requests related to voter rolls have helped uncover votes “that were illegally cast from dead people or people that didn’t legitimately live in the state of North Carolina.” In rare cases, federal prosecutors have pursued those allegations: 19 noncitizens living in the state were charged with voting illegally in 2018, with an additional 19 charged in 2020. (No vote alleged to have been cast illegally would have altered an election’s outcome.)

Although he acknowledges that requests can be time-consuming, Womack says state law clearly entitles residents to examine records. He believes election administrators should recognize that obligation and respect the public’s right to know.

“The impression I get from interacting with state and local officials is that they think they’re smarter than we are, they know what a fair election looks like, and we don’t need to know what they know,” he says. “It’s an attitude of hubris that doesn’t want the general public to know all the dirty little details about how they do their business.”

Womack says North Carolina’s elections officials should seek additional support from the state’s legislature to help provide records. But Gannon from the state elections board says that lawmakers have largely failed to fund administrators’ requests for more resources.

The board asked for more than $16.5 million to expand its capacity in the latest budget. The Republican-controlled legislature allocated just $6.9 million, almost all of it one-time funding to upgrade software and implement the state’s controversial voter ID law. (None of the budget’s three primary sponsors — Republican Reps. Dean Arp, Donny Lambeth, and Jason Saine — responded to requests for comment.)

Nevertheless, both state and local officials say they’ve learned a lot from the past several years and are better prepared for 2024. Gannon notes that the NCSBE is spending roughly $8,300 per year on software to track records requests, and in 2022, the board found over $60,000 to hire a temporary contractor for records responses. State administrators have also developed substantial guidance on what records are actually public to make future responses more efficient.

In Buncombe County, Duncan says her office has started working more closely with the county’s main communications team to coordinate records requests. Like the state, the county has adopted new software, which allows staffers to combine duplicative requests and speed up legal review of potentially sensitive documents.

Perhaps most importantly, Duncan says, she’s trying to be more proactive in outreach to the voting public. She wants those who might be skeptical of elections to connect with the actual people behind the voting machines, rather than online rhetoric.

“There’s so much competing information out there,“ says Duncan. “I think trust happens most efficiently when you can come and talk to a person, and so we want to be really open about that.”