(bright music) - [Announcer] Funding for "The Hinckley Report" is made possible in part by the Cleone Peterson Eccles Endowment Fund.

- Tonight on "The Hinckley Report," our expert panel takes a deep dive into the world of campaigns, messaging, and strategy.

Between the 24 hour news cycle and social media, how do candidates break through the noise?

What tactics have worked in the past?

And what is the future of winning elections?

(compelling music) Good evening, and welcome to "The Hinckley Report."

I'm Jason Perry, director of the Hinckley Institute of Politics.

Covering the week we have Becki Wright, founder and CEO of Proximity, Dave Buhler, professor of Political Science, and Frank Pignanelli, political commentator and lobbyist with Foxley and Pignanelli.

I'm so glad to have you all here tonight on a special episode of "The Hinckley Report."

Tonight we're talking about campaigns, and the three of you are experts in campaigns, and it is so interesting to see what's happened over the years, what's happening right now, how candidates try to reach us, the tools, the tricks, all the interesting things we're gonna get to tonight, and you all have such great exposure to this, as you know, you help run campaigns, Becki, both of you have run for office, the Senate, the House.

You've advised many people, and so I wanna really start with sort of a high level approach to how campaigning has changed over the years, because it has.

There's some things are probably still the same also, but how we're approaching it.

Why don't we start with you, just what you have seen in campaigning.

- Well, first of all, campaign duration has really increased.

So people are running for office, they're starting earlier, and because of that, they have to spend more money, they have to have more tools at their disposal in being able to reach voters in different ways.

You had, with the advent of even radio, that was when we first started out having, you know, a new change, a new tool.

Then we had social media, and there's all different kinds of things that are happening there, and now AI, all kinds of things that people wanna use, tools and resources.

- Yeah, interesting to say these tools, 'cause they have changed.

Some of the final outcome, we know- - Yes.

- That has not changed, but how we get there is another thing.

How have you seen it change through your career, Dave?

- Well, I think the social media, the advent of social media, the ability for candidates to communicate directly with our voters without going through the press, without doing paid advertising is a big one.

But also one of the challenges is where people get their news, and that so many people are getting their news from social media, which may or may not be accurate.

- Yeah, absolutely.

I wanna break some of that down in just a moment.

How about you, Frank?

- Well, first of all, for the benefit of your viewers in the political class, a political campaign is, a good one, it's like a piece of artwork.

It's like a well-directed movie or a good football drive.

You have the execution of strategy, you have the people involved that know what their audiences need, and they play to that, and that's what a good campaign is.

They use the tools, and I just love watching a good campaign.

To me, what I've observed is three different things that have happened, one is the population of the state.

When I was first elected to the House, you had 20,000 in the House.

You now have over 40,000, and that impacts all of the offices, so that changes the cost and how you message and things like that.

The third thing is mail-in balloting, because, you know, when I was first was running, you had election day, you had one day to vote.

And then when we started the mail-in balloting, a lot of people send in their ballots early, and now they're holding on to 'em.

So you have people holding their ballots thinking about what they're gonna vote for.

That also changes how you talk to your voters.

And the third thing is social media.

The thing about social media is that it's cheap, but the rate of return or rate of investment is so high because TV and radio is expensive, where social media is inexpensive, and can target, and you can also extract the information back, so that is also a big component in changes that have occurred.

- Yeah, so Dave, how does that change in terms of the sort of the TV because, and there was a time when that was the first thing we talked about, how we raise enough money to get the right commercials and the right stations at the right times, a little less important now?

- It's still important, but it is becoming less important.

And of course, there's also so many other television stations.

I mean, when I was first involved, you had three commercial TV stations.

Now you have cable, but also you have to, you need to advertise on social media, and some of that is paid, and a lot of it is unpaid that you just can use to reach out to voters, like Frank said.

- Yeah.

So how are you using social media now as you're advising and your running campaigns, Becki?

- Well, running a campaign is actually like running a startup.

You have to create something from nothing, kind of as fast as you can.

There's all this strategy, and creating this beautiful product, absolutely, Frank, but really people, a lot of times, are going very quickly.

They're trying to figure out what can I do right now?

How can I reach voters?

Nothing's gonna ever take away the fact that you need that one-on-one personal connection with the voter.

You need those multiple touch points to convince someone to vote for you.

But all of the tools that exist, they've all changed.

We have to look at, okay, we used to use TV, but now Gen Z and millennials, they are not using TV in the same way.

So you look at it just from a, you know, market-based solution, how can you find and reach those voters in a different way?

- Yeah, so it's interesting, Dave, you know, there were some times when I've worked with candidates over the years, and the idea was, you know, that because these folks always say, "I just gotta shake enough hands."

- [Dave] Right.

- If I just shake enough hands, I'll win this thing.

That's not really the case, 'cause you can't shake enough hands.

- [Dave] No.

- [Jason] So how you, how you're shaking hands now is through these, you know, social media.

- Well, that's right, but also voter contact, and it may not just be the candidate.

It should not be just the candidate, but their campaign team, their volunteers, and these tools can help with the voter contact.

But I think it's even more important because there's so much noise out in the atmosphere, and so to be able to talk to voters and of course, target those who you can persuade, because many of the voters, especially in a partisan race, they're going to vote with their party, and so you've got really a pretty narrow slice of voters who are persuadable, or how to activate your voters in your party who don't always vote to make sure that they do vote for you.

- So how do we persuade, how do we find the people that are persuaded?

- Well, obviously, you have to do the research, and you have to conduct the surveys and identify people in this, and what's interesting is how political campaigns are very similar to like commercial campaigns for products.

You went and you go find, okay, the people who drive this kind of car purchase this kind of deodorant may be more willing, susceptible to this type of messaging.

You do those kind of things in politics too, so you're slicing and dicing, and with social media, you could target that.

And you see, not even in political campaigns, for example, one of the things that we do back in DC is the geofencing, where you use Facebook and others- - [Jason] Describe that a little more, 'cause I think it's a very important term.

- Yes, what we've used, when we know there's an issue, like in DC or even at the state capitol, we've done this, and you've got the staff, it's not so much the elected officials, we've got the staff, they're logging onto social media sites and you're able to use like a Facebook or whatever to make sure that they're getting pop-ups about this particular issue.

And they're the ones that are driving the decisions, so it's both, that happens in political campaigns and in public affairs campaigns where you're targeting a certain audience.

In this case, it may be staff, another place, maybe some other group with social media ads, and it's not that expensive, but it's very effective.

But so when you're running a political campaign, you're, okay, these are the people I need to get to, or this particular neighborhood cares about this issue.

Instead of sending a mailer across the whole district, you can target that area knowing that's the issue.

That is big.

Even though it's still expensive, it makes it more cost-effective.

- I just wanna add that efficiency is what is really allowing people to reach more voters at this time, but then along with that comes this ethical question is we're looking at look-alike audiences, custom audiences, and people are getting trapped in these social media, you know, echo chambers, where maybe you're seeing a different targeted ad than I'm going to be seeing, because you like the Beach Boys and I like Led Zeppelin or something, you know?

And someone has created that under that social media geo-fencing, and then what that does is we have totally different views of the candidate, of the issues, and where's the ethical?

We wanna make sure that the free-flowing of ideas is happening, so where's the ethical push and shove there?

- So how do you find me?

So I'm out there.

Of course, I feel like I'm completely, you know, got my own opinion about everything.

But how do you find me as for a candidate using these tools?

- Well, a lot of times using social media, there's a lot of tools that we talked about, micro-targeting.

- [Jason] Yeah.

- They have pixels that exist when you're visiting other sites, and then you come to social media, and you pull those pixels along with you.

So then really strategic campaigns can look and say, "Okay, I wanna see what he's talking about on this other part and now bring it into social media, and I want him to be part of my audience that I'm reaching."

- So Dave, that's a big jump from when you were campaigning.

- It is a huge jump, but you know, one thing that hasn't changed is a candidate, to be successful, has to come up with the right message, and a message that will motivate voters to vote for them.

Sometimes candidates have something that's motivating them to run, but it may be that the general public doesn't really care, or the target audience doesn't care.

So there are some things that are still constant with how they've been, but these new tools add a lot of new ways to reach voters.

- What do campaigns do to test messages on people?

- Well, sometimes they'll do focus groups if they're a large enough campaign and can afford that, where they bring people in and test things out to see how they work.

But even the most, you know, the smallest campaigns like a city council, just talking and listening to voters can also give you, you know, good feedback on what's working and what isn't working.

- Well, and in the marketing world, we call that test and learn, right?

You set something up, you see it, you test it, and you learn from it.

That's the same thing with campaigns.

You're gonna test and learn both digitally, in person, your messaging, all of that's gonna happen.

And campaigns have to be ready to pivot at any moment.

Candidates are not, you know, in a silo.

They have campaigns that are running against them, and other issues that are happening in the world, so they've gotta be ready at any moment to really make a change.

- Frank, do you have some examples of that?

Not exactly the kind of the messaging that didn't work, but how you've used that information that you've gleaned, 'cause I know you've done it before.

Sometimes campaigns will put this brilliant commercial, you know, forward.

They have it created, and they realize, wait, no one likes that commercial at all.

- Yeah, where I've every really seen it is, well, one of my partners, Renee Kelly, she's known as the referendum assassin, because she can go kill these referendums.

What she does is the research, because what has happened, some will say, "I know that this project is a good project because we're going to do this type of road through a neighborhood" or something like that people will like, so they can have, they'll develop this thing, and we do the research, and shows that people don't want it, but they go ahead with something, and it just drops.

You know, instead, we have to go back to do the research.

What is it that people are going to respond to?

Because that's how you build your campaign plan is based upon that.

I mean, there's lots of examples where someone will come out with a statement on or a position on something, and where you're seeing this happening is on what's happening in the Middle East.

You have politicians saying, "I'm with Israel," but that's not necessarily resonating with the younger crowd because they have different experiences, and so they're now having to adjust to that.

And so it's also happening with the Great Salt Lake too, because a lot of older people have a different view of the Great Salt Lake than younger people do, so they have to shift their messaging on the campaigns.

- What's interesting as we start trying to target and do messaging is the amount of misinformation that exists out there, and there is a lot.

Becki, when you talk about, because you mentioned it at the opening here about AI, you know, artificial intelligence, how is this impacting the political world?

What are you seeing, and what do you see kind of coming in the future as this really takes hold?

- Well, AI has been around for a while, but really it's become much more of a news cycle, hot button topic right now.

And specifically in campaigns, people are really worried about deep fakes.

They're worried about how AI is going to be used to misrepresent different candidates.

Now, misrepresentation in campaigns has happened for years.

This is just another tool that people are going to be using.

The thing that I also wanna touch on is AI is actually very beneficial when you're looking at data.

There's large amounts of data.

Political data is a really important tool to use when you're running a campaign, and so using AI to cipher through that data and say, "Okay, what is my micro-target?

What is my message here based on these polls, based on what is happening?"

So I think that we shouldn't just be afraid of AI.

We shouldn't say, "Oh, this is going to hurt everything."

It's a very useful tool in campaigns.

- [Jason] To that, oh, go ahead, Frank.

- So if you look at the history of small business development, before, we have taken months for a small business to get started to follow paperwork and things like that.

Because of technology, you could start a small business in an afternoon.

Same thing with the AI in a campaign, what may have taken weeks to develop a piece of literature, a website, you could take that information, stick it into an AI engine, out comes out a website, literature.

You have now reduced the cost of at least initial entry for a candidate because of AI, and that's one of the really incredible things about it.

- So Dave, this is such an important point right here too, because, you know, as we've run campaigns in the past, really it's all about the data too, right?

So if you wanna do some targeting, you gotta know who the people are, but this has really changed that.

No longer we just calling the party saying, "Please give me a list of registered voters."

- That's right, you can really get micro, and one way to maybe illustrate this, we've all had the experience where we've gone on a site like Amazon to look for a product, and then all of a sudden, in all of our social media, we're getting ads for that product, whether or not we bought it, and it's the same thing, but applied in a political way.

- How does this information help you pivot, as you mentioned?

Because sometimes you have to do it pretty quickly.

- Yeah, I wanna go back actually to what Frank was saying with AI and understanding the data, and understanding that.

When you've got the AI component of things, you can put something together in a moment.

So if you're pivoting and you need to change a message, you can do that really quickly.

We can throw up a website in 24 hours, whereas it used to be thousands of dollars and lots of development behind the scenes and in person having that happen.

Now you can do that really, really quickly.

- What's interesting is part of this pivot, and I do want to get to maybe the potentially negative side just a tad, because it is getting increasingly hard to know if what you're seeing is authentic or not.

And there's some political science professors, and both of you have been that, and so I'm kind of curious how you see this happening.

And there's this phrase of some political science professors called the liar's dividend, where it used to be, we'll just say something's fake, but if you can't really tell the truth from what is not true, maybe when something really is true, you wouldn't recognize it, Dave?

- Yeah, well, there certainly is a great potential for mischief too, besides the positive things that we've talked about, but I think another thing that really has changed for campaigns is their ability to communicate instantly with their supporters.

Where maybe it used to be we'd have to send them a letter in the mail or maybe call 'em on the phone or put an ad up, which would take a couple of days, now if there's some misinformation that the campaign wants to bring to light that my opponent is misinforming you, they can send it out on Twitter or on other social media platforms instantly, and of course, to their core supporters, have the mailing, you know, emailing and things like that so that they can correct the record if they need to very quickly.

- So one of the dynamics that is happening, I mean, even before AI was coming around, people distrusted traditional media.

I mean, it just, that's who we are.

But what is happening, look what happened to Celeste Maloy's campaign.

You always have endorsements, but her endorsements of local elected officials really played into her success.

I believe as more and more people become suspicious about AI, you know, the President Trump hugging Fauci and stuff like that, people are gonna be, they're gonna start putting a filter on, 'cause they have been doing it for decades, if not centuries already.

So those that try to cheat with AI are, I think, gonna have a hard time.

What is going to happen, in my opinion, more and more people can rely upon, okay, what does my neighbor think?

What does my kid's soccer coach think?

What does that business leader think?

So more and more, and that's a good thing, they're gonna rely upon leaders in their community to really give them some direction of what this candidate is about, as opposed to some picture that was fabricated.

- Well, and that's where we actually need government to step forward and give us some guardrails on what is accurate, what can help people.

That's where we wanna step in and have government create those guardrails to help make sure that the AI is not going to be dangerous.

So we're looking at different states that are coming forward and saying, "This is not acceptable.

Deep fakes are not acceptable, they're punishable by law."

We need to have those types of things across the nation so that people can have, you know, sincere understanding of what's happening.

- To that good point, so far, we don't have federal laws in place, but states are starting to approach it in a patchwork sort of way.

- Absolutely, so back in 1973 actually, there was, I think it was Minnesota or Wisconsin that said you can't actually impersonate someone and make something up that would be very damaging for them on the campaign.

But then since that time, since 2019, they've specifically looked at deep fakes AI components across California and many other states across the nation.

- The reason she's quoting 1973, where that came about was in 1972.

I'm old enough to remember this, (all laughing) is that you had the leading Democratic nominee to challenge Nixon was Edmund Muskie, and the Nixon burglars had fabricated this letter, it's called the Canuck letter, and he was reading it at airport, he started crying because it was fake.

Everything in this letter was fake.

There's misspellings that Edmund Muskie never would've made, but because he broke down and cried, it just torpedoed his candidacy.

And so states said, "We don't wanna have this ever happen again."

But we've had false advertising since then too.

So there's going to be reactions to this, but we've always had this happen.

Look at the campaign of 1800 where Jefferson and Adams were calling all sorts of names.

- That was- - It was awful, and so this has always been around, and so yeah, you can have the laws, but you're going to have to have a public that's trained to be perceptive say, "I don't know if I buy this or not."

- So Dave, how do we get that?

Because it seems like we're gonna have to be increasingly sophisticated.

- Well, we are, and I think that having voters that are well-informed is the most fundamental thing for democracy, and so helping to, that's one of the things I love about teaching students at the university is to help them to walk out being better informed and knowing how to stay better informed than maybe they were before.

But I think that a great point has been brought up that as these deep fakes and things like that become more prevalent, it very well may be that the voters will just tune it out, sort of like they do with the negative advertising that comes from super PACs and things like that, that we've seen in our congressional races in Utah, and senate races.

- Can I add to that?

I think you make a great point, and another thing I would add is say we need more people to run for office.

Everyone's thinking, oh great, a world with more politicians?

Yes, actually, I'm gonna argue for that.

We need more people involved.

We need more people stepping up and saying, "I am available to run for office."

And when they do that, they'll be able to understand the process better, they'll be able to trust the process better, and they'll be able to have a little bit of empathy for those who are going through that process.

- There are other interests out there that are trying to impact these campaigns and get to us as well, and Dave just mentioned it, but maybe Frank, you can talk for a moment about these super PACs, because there are groups, not campaigns.

Maybe you can give us a small primer on the rules there, and then how they're trying to get to us.

- Well, ever since the Supreme Court decision which allowed the development of these super PACs, you have these super PACs that go out and they raise money usually from other PACs.

PACs is short for political action committees, because usually a candidate has their own political action committee.

Now, these special interest, and it may be any type of interest that it's on the left, it's on the right, it's in the center, you name it, they raise money, but they're not allowed under federal law to coordinate with the candidates, so there's no conversations, direct conversations.

All they could do is raise those issues.

They may say, we support candidate X or we support this issue, but they cannot coordinate with a candidate, but funny games are played.

So if you're running, if you're organizing a super PAC and you wanna support a candidate, you can't talk to that candidate.

What you can do is that candidates will post things on their website, like pictures of their family and stuff like that, or where they are in a position.

So that super PAC takes those pictures and uses in their campaign commercials, so that way there's this indirect contact that's happening.

But what does happen is they're like another column of forces in addition to your campaign, you have super PACs that are also banging away, do the same thing that your campaign is doing, targeting voters and things like that.

So it's a new element to American politics, but it's also a way for people who may not so much support a candidate, but support a issue could participate in that process.

- Dave, how does this work in terms of the sort of the money in PACs?

I wanna talk about that for a moment, 'cause what campaigns need is they need name ID, and they need money, and sometimes a little time.

- Right, yeah, and what we've seen in Utah with the super PACs, the ones that will come to mind most readily are in the fourth Congressional district and in the Senate race last time with McMullen and Lee, where there's a lot of national interest, and lots of very negative advertising.

A lot of the research shows what this does, after a point, you get to a saturation point where they're not persuading people.

What they're doing is turning off people, that those voters who are more maybe on the fence and not really in one camp or the other are just like, "I hate it all, and I don't even wanna vote."

- Yeah, so Becki, what's interesting is sometimes, there're a bunch of groups, I wanna talk about two primarily.

Sometimes the negative ads, a candidate will put out, say, "I wanna correct the record," or something like that, and sometimes it is fully in the hands of these outside interests.

- Absolutely, there's a lot of signaling that occurs, and as Frank mentioned, you can't coordinate actually between PACs or super PACs and candidates, but signaling occurs on really sophisticated campaigns, where they'll post something, they'll mention this thing and then, oh, pull that ahead, and the super PACs are saying, "This is important to us, 'cause we support this candidate," so that signaling happens a lot.

Additionally, I wanna bring up that even though we're talking about super PACs who are spending lots and lots of money, there are influencers, social media, all throughout the world who, they may not be spending as much money, but they have thousands and hundreds of thousands of followers, and that's a price right there.

That's a cost where candidates are reaching out to these influencers, reaching the new generation, and finding ways to figure out, okay, how can we make the biggest bang for our buck?

- Yeah, Frank, how is that working?

Because it clearly is true.

You try to identify people who are trusted in those key communities.

- Yeah so, and by doing that, by targeting that, getting those people who are trusted, those are the ones that really you need to focus on in terms of having influence, and it works in reverse.

What happened in 2016 is you had these key influencers in the key battleground states.

They were telegraphing back to the Clinton campaign and to those super PACs saying, "We think you're in trouble."

They ignored it, in fact, what the Clinton campaign did is they put more money into states that they thought, okay, we're gonna expand our electoral college.

They ignored Wisconsin, they ignored Michigan.

But the key people were saying, "No, we think you're losing."

So if you're gonna develop that relationship with these key people, you need to listen to 'em, and not just persuade, but survey 'em, find out what they're thinking, because if you don't, you're not gonna be able to pivot, 'cause they did not know how to pivot because they weren't listening.

- The other thing that happened in that campaign is Trump was able to mobilize people who normally don't vote, and so that was kind of an untapped resource.

It's easy to look for the people who always vote, and you know they're always going to vote, and if they're on your side or not, but to try to motivate people who I've never voted, but I'm gonna vote now because of something this candidate is saying that hits me emotionally.

- Our last couple of minutes, I wanna talk about sort of an effort, maybe the state of Utah's key part of this, and maybe we'll see this goes nationwide, Becki, really this idea of civility, of dignity in our conversation.

Our own governor is out there saying, "In spite of all the things we've talked about, we must be civil to each other."

Talk about why that is resonating a bit.

- Yeah, this time last year with the Salt Lake Chamber Public Policy Initiative, Arthur Brooks spoke to this chamber and talked about disagreeing better, talked about running to those that we disagree with, who we are seeing as completely opposite of us, and learning from them.

And then the governor has then, with the governor's association across the nation, encouraged everyone to disagree better.

So when I say I want more people in politics, I mean it.

I want more people running for office, I mean it.

I want us to learn how to disagree better.

I want us to be at this table hashing out ideas and policy, and figuring out a way that we can actually have nuanced discussion around really important topics.

- Yeah, so it's such an interesting point.

Dave, you've been in campaigns, you've advised people so many times, and it's a great principle right there until you start feeling like you're losing.

- (laughs) That's right, and I think for it to really affect elections, it would have to be that the public have bought in, and that they say, "Oh, this candidate is not ranked high in the dignity index, so I'm not going to vote for them."

Until that happens, I think campaigns are gonna be watching with interest, but still kind of doing business as usual.

- Frank, mind giving a moment for this?

'Cause I think you're a good model of this also.

How do we get candidates across the board to listen to this message and maybe reward, find a way to reward good behavior and less reward in that?

- I think we have to say, and I really commend the governor, I think we have to say, "We want you to be passionate about your arguments.

We want you to fight what you believe in, but don't attack that person personally."

I think we have to start setting the standard of be passionate about what you believe in, but if someone's attacking someone personally because of their belief, that's where you have to draw the line, and that's being fuzzed over right now.

It's like you're back is you believe in this, and that's accepted in the media, it's accepted in the educational institutions, and even religious organizations, where we've got to start drawing the line.

We want you passionate, but this is another human being, and you need to be respectful.

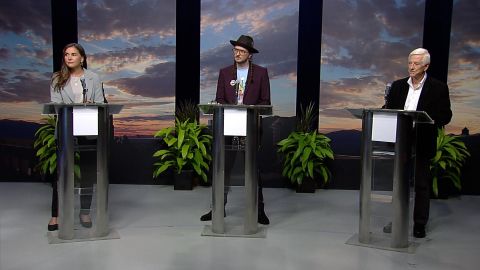

- Well, and in CD two, the debate between Celeste and Kathleen, that was a very civil debate, and they have totally different views on things.

It was really great to see two women coming forward and modeling that behavior within a debate for that congressional district.

- Absolutely right, we did see that, and you've given us great insights this evening who else to pay close attention to.

And thank you for watching "The Hinkley Report."

This show is also available as a podcast on PBSUtah.org/HinkleyReport, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Thank you for being with us.

We'll see you next week.

(bright music) (music continues)