On the two year anniversary of the January 6th insurrection, Yale historian Joanne Freeman reflects on the enduring legacy left behind by the attack on the Capitol, and what it means for our democracy now: “What the lying did, what the erosion of faith in the democratic process did, was teach people to not trust the electoral process. “

Molly Enking: So, last year you wrote in The Washington Post reflecting on the January 6th attacks, quote, “Our government is still under attack. The offensive is quieter now, but no less menacing, eroding the government from within. The fundamental right to vote is under siege.” Can you tell me what we’ve seen to this effect over the past year?

Joanne Freeman: Well, you know, it’s interesting, I think because January six was so dramatic with such a major event. And there have been hearings and the hearings have ended. I do think a lot of people are prone to assume that somehow or other it is over, which it isn’t. So we’re in a different place now than we were on the original day of January six. But we’ve been witnessing in a variety of different ways still people trying to tangle with and get in the way of the democratic process. Elections, you know, secretaries of state in various states seemingly prepared to do things that are not necessarily in line with how a democratic election works. So we’re seeing erosion from within. Still, it’s scattered among the states to a large degree. So in a way, perhaps even more threateningly, we don’t see it. And yet it’s still happening. You know, it’s it’s an interesting time to be a historian because and a political historian, particularly, because on the one hand, I want to preach to people and say, you know, just because in this moment it seems as though something has ended, trust me, as a historian: endings and beginnings are not that neat. And we have to be alert and we have to be aware. And yet, if you say that too loudly, too often, people aren’t going to hear it anymore. So it’s a, it’s an interesting moment to be a political historian or a political scientist because you’re you’re trying to send a message that, on the one hand could sound kind of dire. We’re better shape than we were at that point, but we’re not out of the woods.

Molly Enking: Absolutely. And to that point, let’s talk a little bit about the damage that the “big lie” has done to our democracy already. In the midterm elections, anti-democracy or “big lie”-candidates seemed to have a lackluster performance. Does this mean that the big lies’ influence on our democracy is fading?

Joanne Freeman: Well, that was encouraging, right, that some of the people and particularly secretaries of state, but some of the people and I’m almost not thinking like I want to use “the big lie” because that almost normalizes it. People who deny the actual election. Some of those people did not win, or far fewer of them than we feared might. So that’s a good thing. That’s a positive thing that, you know, democracy sailed through

I know that the big lie is an easy way to sum it up, but I hesitate to use that because it almost normalizes it in some way. It kind of brands it. People do democratic process. A lot of them did not win office, which was wonderful. Some did, which is not wonderful. A lot of them did not. But that doesn’t mean that—I sort of feel like I’m the voice of direness, right? It doesn’t mean that the damage is undone. Because what that did, what the lying did, what the erosion of faith in the democratic electoral process, what that did was teach people to not trust the electoral process. Whether that lie is still in place or not, that damage has been done. And it will take, I think, assertion on the part of a party that really wants to engage in democracy and the democratic process to start to repair that. That’s not pure. That can be done in a day or a month. That’s a serious undermining of our political process. And the main thing that makes us as a country and preserves us as a country is the constitutional political process. So if you are jumping in and denying that or tossing it away or negating it in some way, that’s the essence of what holds us together. And without that being assumed to be enforced and really without good faith assumption on both sides, and particularly on the left, that the right will engage in the kind of constitutional pact we have with each other. That’s a that’s a serious problem. And I don’t as a historian, I don’t have the answer to what to do about that. But it’s really important to think about in a way, what we’re watching in the House right now is a part of another version of this, we’re watching a small group of people, uncompromising extremists, hold the house hostage. That’s what we’re watching and that matters. It says a lot about the Republican Party and it says a lot about where the nation is right now, too. And you could say the same about January 6th.

Molly Enking: And that actually leads right into my next question, which is about House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy. He once called the January six committee a sham committee. And what would it mean if he is successful in being elected House speaker? What would it mean for someone with that perspective to be third in line to the presidency?

Joanne Freeman: Right. Well, third in line to the presidency is not comforting. You know, I said a lot in recent years about why I thought the hearings on January six were vitally, vitally important, regardless of the outcome. I think a lot of people thought, what, “big deal.” Right? That’s some people. Maybe McCarthy thinks it’s a sham. Other people think, ‘so, what? You know, whatever, it happened.’ But the fact of the matter is, what happened in the hearings was that people essentially that Congress drew a line in the sand and said, you know, the committee said this is beyond what is acceptable in American democracy. That was really important to do. No matter what the outcome was, it had to be done. Imagine if January 6th happened and there was no broad, strong government response that said this is out of bounds. Imagine what that silence means. Silence means so much right now. Silence is part of why this group of people are holding the house hostage. The rest of the Republicans have been silent while these people have been very extreme in their claims. Now they’re living with the implications of fostering this kind of behavior. Silence really matters. So I think hearings, they happened. It’s important, important for the historical record.

Molly Enking: And speaking of the January six commission, what were some of the key takeaways, as they relate to democracy, from that committee?

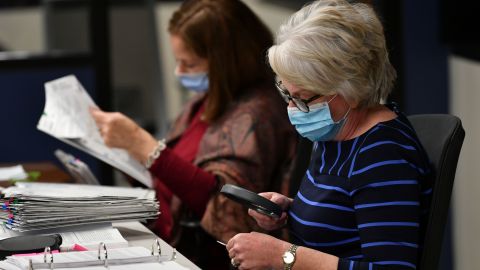

Joanne Freeman: Well, you know, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about one of the upsides of our current moment of political upset is that Americans are sure learning a lot about our political process, all kinds of things, right? How does the impeachment process work? What happens? How do you elect a speaker, and the election process itself, right? One of the takeaways was from election workers who explained exactly what they were supposed to be doing. Showing what happens when you engage in ballot counting, showing the process, showing the electoral process. That’s one of the takeaways is just, there is a process. Another takeaway is, by mentioning Kevin McCarthy, it’s really frustrating to know that despite that and despite all the evidence, there are still going to be people that are like, yeah, you didn’t prove anything, but that is the age we live in. The age we live in is an age of what do we want to call it, blustering and lies. But I still think that the existence of truth makes a difference. And I still believe that Americans who are watching what happens and understand democracy and understand how it works and are willing to defend it not with violence, but with standing up to people who are trying to stamp it out. That’s the way we’re going to survive this. But that’s we need that kind of awareness and action on the part of Americans.

Molly Enking: You spoke earlier about: history shows us messy beginnings and endings to these types of chapters in history. What, what might we expect in the foreseeable future when it comes to this chapter of, you know, messiness and “lies,” as you said?

Joanne Freeman: Well, this is always hard, right? I do think as a historian, part of what I would say and I hinted at it earlier, is what we’re seeing now won’t end with one election. It won’t end in a day or a week. We’re watching a moment in Democratic politics in the United States, and how that works, what doesn’t work and where it’s unfolding in front of us.

And just as when you study people in history, I study people before the Civil War, and when I study them, I have to remind myself that they don’t know what’s coming. We don’t know what’s ahead.

It’s the contingency of this moment that matters so much. It’s the fact that we don’t know what’s coming next. And maybe something wonderful will come next and maybe Americans will really have a sense of what should be happening and they’ll stand up for it in a moment of instability. And that would be wonderful. Maybe something not so charming will happen. And that’s possible, too. And that’s the most important thing for folks to realize about the current moment is we actually don’t know. And it’s the unknowingness that’s most important for us to realize, because that will enable us to see that it’s a time to take action and not to be silent.

Joanne Freeman: It is true that when you look in the past at major crises in American history, and particularly American political history, very often at their close, you do see some kind of a reset. Sometimes that takes the form of a presidential election. Sometimes that takes the form of a Supreme Court decision.

In the presidential election of 1800, which is the first really contentious election that we had. And it was really contentious. They were well armed and ready to take the government for Jefferson if things didn’t go the right way. Jefferson was asked afterwards what would have done, what would you have done if things had gone the wrong way? And he basically said, oh, you know, we’d have a convention and tweak the system a little so it wouldn’t happen again and on we’d go. So there are ways to reset, but they rely on the political process. They rely on Americans of all kinds buying into and accepting and agreeing on at least nothing else, the bare basics of the Constitution. Now, of course, people have never agreed on what is right. There’s all kinds of disagreement on the Constitution and what it is. But if you can’t even agree that the Constitution itself is the essence of who we are, and if you can’t even agree about what’s in it and I mean, on the most basic level, for example, impeachment is in the Constitution, people who were saying impeachment is unconstitutional, that’s a problem. It’s in the Constitution. So I think part of the answer to this is there are reasons, but often those reasons rely on the political process elections, the Supreme Court decisions. And again, we’re in this moment where there are some people who aren’t thrilled with the system. And January six represents a moment when people were plunging into interrupted, and that’s part of the of January 6th. What it implied is the fact that these were people who were just going to interfere with an election and deny it.

But let me say this for a minute. One of the things I find myself. Thinking about at this anniversary of January 6th. It is. How do I feel about the state of the nation now versus how I felt on the day it was happening? I will never forget how that felt. I will never forget the trauma of it, the disbelief of what I was watching, the fundamental ways in which they felt that America was under attack, and then the ways in which people did not. All of this. Oh, you’re exaggerating. No. But I’ll never forget the emotion of that and what it meant. And I bet there are a lot of other people who are the same way. But now here I am much later. And it’s interesting to think about what I was thinking about January six. I certainly think it will always be an important anniversary that needs to be remembered because it’s thus far the ultimate political electoral evil. It was an attempted coup, and I’m just going to say it was an attempted coup against the government. It was it was an attack to overthrow an election. We have to remember that. We have to think about that and we have to not let it be normalized so that it’s just a thing that happened. We need to keep feeling bad about it. I hate to say that, but it was reassuring to me during the hearings that when I saw the clips of what happened that day, they were still upsetting. We really have to not let ourselves forget our emotional response to that, because the emotional response to January six is a real visceral indicator of how important it was.

Molly Enking: Joanne Freeman, historian at Yale University, thank you so much for joining us today.

Joanne Freeman: Thank you.