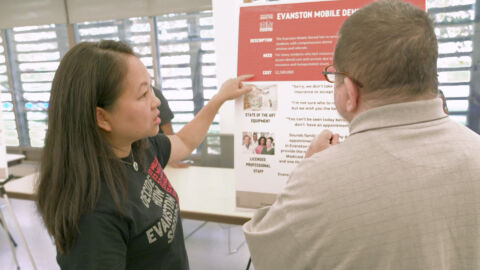

In Part Two of our “Value Norms” reporting, A Citizen’s Guide visits Boulder County, Colorado, where the Clerk and Recorder, Molly Fitzpatrick, and her staff are implementing programs that provide the general public with a nuts and bolts look at how elections work – in hopes that making the process more transparent will also raise the public’s acceptance of voting outcomes as legitimate.

Respecting elections officials is one way the U.S. can get back to the norm. In his book “The Bill of Obligations: Ten Habits of Good Citizens,” author and diplomat Richard Haass explains the importance of valuing norms, like respecting elections outcomes or a peaceful transfer of power.

The “necessity of obeying the law is obvious,” Haass writes. “Norms, though, are something else – and, something more. Norms are the unwritten traditions, rules, customs, conventions, codes of conduct, and practices that reduce friction and brittleness in a society. Words like ‘cushion’ and ‘lubricant’ come to mind. Laws provide the scaffolding of a society, but norms are what fill it in and make it livable, the furniture within the building, so to speak.”

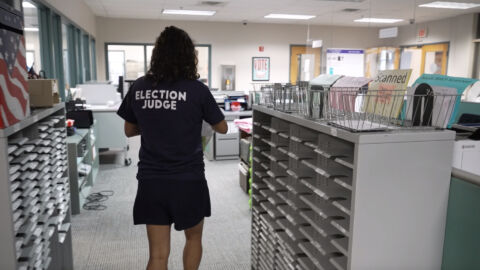

Over several days around each election cycle (including state and national primaries and general elections), Boulder County allows local residents to attend a Q and A tour of its ballot processing center. And it’s a model that other counties are embracing across the country, in an attempt to stave off the kind of (unfounded) allegations of vote manipulation that followed the 2020 presidential election.

Fitzpatrick points out that elections administration is not, “Myself and our full time staff of 14, 15 people overseeing the election. It is hundreds of election judges and workers who are overseeing the election. These are folks that are your neighbors, your friends, church members. They’re doing the implementation in the oversight of the election. They’re doing things like signature verification, checking in ballots, checking in voters, scanning those ballots.”

If getting involved with election day excites you, well, good news: most any registered voter can become a poll worker themselves – and August 1 is National Poll Worker Recruitment Day across the U.S., a civic engagement campaign sponsored by the United States Election Assistance Commission to bring Americans into these paid positions, helping to set up polling places, check in voters, demonstrate voting machine use and assisting with other election day issues and questions. Requirements vary from state to state but the EAC has this handy page to help you “help America vote.”

Boulder is also recruiting high school students who are at least 16 years old to be “election judges,” or poll workers, to engage more young people in the voting process earlier than they can legally pull the lever in the booth. 17-year-old Mills Shanbhag was one of the under-18 student election judges working at Boulder’s June state primaries. He got hooked on politics in 2020 at the age of 13, and says, “As we get closer and closer to elections that are happening, be it the primaries or the general election, I’ve become a little bit irritated that I can’t vote. I think that participating in an election, even though I can’t vote, is the best thing I can do to help support the democracy that we all live in.”

Many states have also passed similar student election worker statutes; check all your own state’s poll worker requirements, here.