|

|

|

An interview with David Breashears:

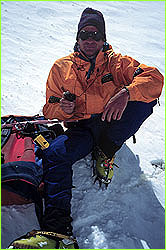

An interview with David Breashears:Sticking by the Rules at the Top of the World Moments after achieving his fourth career ascent of Mt. Everest last May, David Breashears sat down in the snow to answer a battery of psychometric questions radioed from Base Camp, 11,400 feet below. A sample: "If you see a picture with a diamond, a rectangle, and a circle, and the circle is to the right of the rectangle and directly above the diamond, is the rectangle right of the diamond?" Breashears breezed through, barely slowed down by the paltry oxygen reaching his brain in the perilously thin air—a feat he credits to years of disciplined thinking at high altitude while making documentary films. Breashears contributes multiple talents to NOVA's gripping science adventure "Everest—The Death Zone," airing Tuesday, February 24 at 8pm ET on PBS (check local listings). He is the film's expedition leader and co-producer, as well as one of its guinea pigs in an unprecedented series of psychological and physiological tests designed to measure how the mind and body deteriorate in the course of an Everest ascent. Breashears, 41, recently answered a battery of less analytical questions from his Newton, Massachusetts home, where he is currently in high demand with a just-published National Geographic book and an upcoming IMAX film—in addition to his NOVA documentary—on the world's tallest, most unforgiving peak. NOVA: I have problems with the question about the diamond, the rectangle, and the circle here at sea level. But they were asking you that on top of Everest. David Breashears: And I got it right! NOVA: How did you answer a question like that at 29,028 feet? DB: That day going up to the summit I was thinking about the fact that I wanted to do well on the test. I was climbing with oxygen. Now by the time I took that test on the summit of Everest I had been without supplemental oxygen two or three times longer than necessary to have put my blood saturation level at the level of someone climbing without oxygen. I don't know. It's a mystery to me because I remember a very extreme sense of clarity, even better than I had down low, seeing the answers to the questions. I don't remember feeling confused like, "What's going on here? How do I answer this?" We had been tested on and off multiple times over the past few weeks, so we had that going for us, though the neuropsychologists factor that into your scoring. The first time you hear the test with the diamond, the triangle, and the circle, you don't know that you have to start painting a mental picture of those objects in front of you or you don't have any hope of answering it. The third time you've heard that test, you know that you'd better think that way. NOVA: But still, it must be a mind-numbing environment in which to ponder these questions? DB: That's true. Part of being at those elevations, no matter how well one may do on a test, is that you are really a barely functioning person. Things don't have a big impact. You're not shocked by things. You don't have these great, powerful emotions that you have at sea level, like astonishment or sadness at seeing a friend's corpse up there. There's an extreme pragmatism about everything you do. You'll find that as you talk to people about being high in the Himalayas, they don't often speak in vast sweeping terms with lots of beautiful adjectives. Whereas someone who may have climbed a peak in the Alps at 14,000 feet has a lot to say. A friend of mine put it very well once about climbing on Everest and being on top: "It was a dreamlike sense of disbelief." NOVA: Did any of the test results surprise you? DB: Aside from being surprised at how well some of us did, one thing that surprised me had nothing to do with psychometric testing. You start to realize how little you sleep, how little you drink, and how little you eat once you have to report it every day and add it all up. The way we get up Everest and down it, given the conditions we're faced with, is just that we have to deny what's really happening to our bodies. We just have to believe in our task and not dwell on the impossibilities of it. NOVA: Do you think such stresses—physical and mental—lead to accidents like the '96 disaster? DB: That's axiomatic isn't it?—when people have been on the go for sixty hours on four to five hours of naps—not sleep. They're dehydrated. They're hypoxic. They're malnourished. None of us would want to have sat down and taken our SATs then, would we? I think that in '96 they made bad decisions, somewhat impaired, but with the best of intentions. They kind of gambled. They let their guard down, and there was certain element of hubris in the fact that they were very confident. They had been there before, and generally had had good weather. And they were confident in their abilities to get people down. It's a very interesting and complex mix of what was going on that day. The guides, I knew as very good people whose overriding drive in decision making would have been, "We run this business because we believe in getting people to the top and that is a wonderful experience. We want these people to get to the top." Not, "We have to get them to the top." It's an analogy that always makes me uncomfortable, but I think decision making up there has to be done the way the military does it. Officers are leaders trained that situations change but there are certain rules that are unbroken. Because in the heat of battle, in the stress of the moment, in the fatigue and confusion of action, it's easy to make the bad decision. So you rely on your training. Right? The way I operate on Everest is to rely on years of having certain basic fundamental rules I try my best never to break. NOVA: What are your rules? DB: The big ones are don't let anyone go high on the mountain who will jeopardize their own safety or the safety of the team, and don't climb too late. In '96 they went so far over what was expected in terms of the turnaround time that the situation obviously got out of control. People who are going to be leaders should be trained to rely on principles that have been drilled into them, if only by themselves. On the other hand, it's easy for me to second guess what they did. I wasn't there. But one thing that I do know, that I can say without a doubt—I just wouldn't have been climbing up that late. NOVA: Why do you think the disaster has such fascination for people? DB: Truth is stranger than fiction. You couldn't have invented that story. Rob Hall calling to his wife to name their daughter. Beck Weathers coming back from the dead. I mean, come on! If Hollywood had invented it we would have laughed. A guy lies there and after a night out and being pronounced dead twice, he stands up and walks back. That's Hollywood. No, this is real life. What we all got swept up in was this kind of yearning—which we can all feel and know—what it's like to yearn to do something great, or least perceived as great, and to know that only a magnet, only a mountain with the psychic gravity of Everest could have pulled those people up there. We like to ridicule and criticize them for the absurdity of their quest, the naiveté, the hubris, and the greed. But at one level we understand their basic yearning and passion to go out and do something like that. Otherwise it would not have meant anything to us. We all know that 100,000 people die 100,000 horrible deaths every day. It has to touch a chord doesn't it, to really matter. It wasn't about death. It was about the way they died and what they were trying to do. NOVA: In this film you seem seriously conflicted on summit day in '97, and you voice these concerns over the radio. But you ended up going for it. How did you decide? DB: It was kind of a ritual. I was airing my fears and worries. One worry was that people were playing piggyback on us. The members of my team had ten ascents of Everest between us. There were teams that had none, and they literally were following us up. We went from Camp Two to Three; they went Two to Three. We went to Four; they went to Four. I knew that part of the problem last year was the bottleneck, with climbers unable to get down the Hillary Step because others were coming up. I didn't want to face that, while the weather deteriorated or whatever. I'd rather sit in my tent and have hell to pay later for not getting the summit footage than do something risky. Well, we talked about that and other worries. I realized that if we left earlier, since we were a stronger team we could go much faster than anyone else and get back ahead of any bottleneck. The other thing I worried about is the people on the mountain whose abilities I did not know. It is not in my character to just walk by somebody in extremis. What if we're heading down and someone has collapsed? You end up in a situation where you have to look after someone and you're safety is compromised. In the end I decided, "OK, why not get out of your tent and get moving, and if you're not ahead of people—if it's too crowded—before you get high enough for it to matter, just turn back." NOVA: What time did you leave for the top? DB: We left at 10:30 p.m. and we were on top at 6:50 a.m. The other thing that happened was after the first thousand feet, I was really suffering terrible stomach pains and a burning feeling in my lower esophagus. So I sat down and threw up about five times. I remember staring at this frozen pool of liquid, illuminated by my head lamp, surprised at the bright color of it—it was fruit punch Kool-Aid—and then thinking two things: God there go all my fluids for the day that I worked so hard to get down, but wow do I feel better! If I hadn't vomited, I probably would have had to turn back. NOVA: On the way down the mountain, your teammate David Carter almost died when a bad cough took a very serious turn. How unusual was it that what seemed like a normal cold developed into a life-threatening situation? DB: His initial cough was not at all unusual. In 1985, I had the worst kind of cough and really had problems breathing on summit day. After coming down from the summit I had a huge fit of spasmodic, convulsive coughing, and I coughed up a chunk of stuff about the size of a walnut. I've seen that happen to other people. But in David's case, he had to have a Heimlich maneuver to get it out. That is very rare. What happens, I think, is this. It's so common to have a minor chest infection up there, and after you start using oxygen around Camp Four, or at Camp Three in David's case, you're dealing with air that's even drier and colder than normal, because as gas expands it cools. The air has almost no humidity—it's super-dry—so if you have something that's already causing mucus in your throat, then the oxygen dries it out. It's like getting a shellacking on the inside of your throat—layer after layer of this shellacking. It just builds up. The constriction gets smaller and smaller, and other things start to collect around it. When I coughed mine up, it looked like the lining of your throat. It wasn't your actual throat tissue, but it was like a mold from the inside of your throat, deep down. I think that's what happened to David, and boy we were just so really concerned that night. In 1924 when the British were climbing very high on Everest, at about 27,000 feet, a man named Howard Somervell had basically what David had. He'd had a bad cough and an infection, and something lodged in his throat and he couldn't breathe. He sat down and started to struggle and realized that he had only one thing left, so he wrapped both arms around his chest and squeezed hard and bent over. Out flew this big chunk of whatever we call it, and he said he was breathing clearly for the first time in weeks. He had the same thing as David and no one to give him a Heimlich, so he had a self-Heimlich. NOVA: One thing I'm curious about—when you're up high in the Himalayas for weeks on end, do you have the mental energy to read books? DB: Oh yeah, we read all sorts of things. The quality of reading goes down the higher you go. You might have a book at Base Camp like Frazier's Cold Mountain or Stephen Ambrose's Undaunted Courage. But the higher you go, the more you want just entertainment. I'll tell you some of the big books up high over the years. Shogun was big. The Hunt for Red October was big. Lonesome Dove was big. Shakespeare, Camus, Proust, Nietzsche? No. I think a great book to read on an expedition is Undaunted Courage. I could understand what Meriwether Lewis was going through—not for a four year expedition, but wondering if I have enough of this, how much of that to bring, what are our priorities, how many people should be on the team. One thing that I think reveals a lot about altitude is that people's journal entries up high contain almost nothing but facts. If you look at any journal entry at 26,000 feet there's nothing. "Went up today." "Came down." "Saw the sunset." When you come back down and you begin to unwind and your body soaks up more oxygen, there's kind of this delayed response and you actually start to remember how you felt or wanted to feel. You see such glowing and wonderful things written about being up high on a mountain, but you very rarely hear it on a radio or read it in a journal entry from anyone who's actually there. When you're there, you're in survival mode. Emotions—even pleasant ones—take energy. You're robotic up there. Photo: Pete Athans Lost on Everest | High Exposure | Climb | History & Culture | Earth, Wind, & Ice E-mail | Previous Expeditions | Resources | Site Map | Everest Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |