Last week NASA announced the preliminary results of the moon smashing LCROSS mission that NOVA scienceNOW covered this past summer, and now it's official.

There is definitely water on the moon.

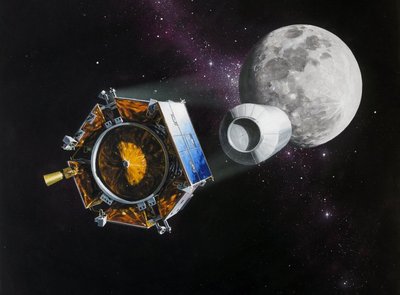

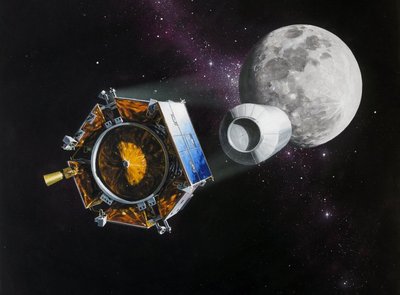

(Image courtesy Northrup Grumman/NASA)

When

we last left LCROSS, in July, the spacecraft was speeding along its slingshot trajectory toward the moon. On October 8th, about 10 hours before impact, the satellite released Centaur--the white, cylindrical rocket stage in the image above--and nudged it into a collision course with the well of a crater on the moon's surface. The rest of the spacecraft followed about 10 minutes behind Centaur, ready to start taking data as soon as the initial collision kicked up enough dust to analyze.

The crash was less dramatic than hoped. Scientists originally predicted that the headlong impact could send plumes of material shooting up to 10 kilometers above the surface--a reaction that would be visible to telescopes across the country. But, perhaps because of the spongy nature of the moon's surface, the dust didn't spray much further than a single kilometer high. At first, the mainstream media deemed the mission a flop.

But in the months following that impact, NASA scientists sifted through the data and found that the plume, though smaller than anticipated, was hardly a disappointment. The results released last week show that plume contained at least 26 gallons of water. (None of that was water in the liquid form we're used to, since the lack of atmosphere on the moon causes solid ice to sublime directly into a gas.)

What does this mean? For one thing, the moon may be more viable as a way station in space than previously thought. If we can harvest and use the moon's water, either to sustain humans in space, or as the raw material for making hydrogen fuel, we might be able to use the moon as our stopping place and leapfrog on to other planets.

But, as our friend from

Reading Rainbow used to say, you don't have to take

my word for it.

Check out

this podcast, in which David Levin talks to David Morrison of NASA's Lunar Science Institute and asks him to explain why we should bother going back to the moon.

Still not psyched about the new discovery?

Hit play to hear "Water on the Moon," a song composed (and performed in part) by LCROSS deputy project manager John Marmie.

Recent Comments