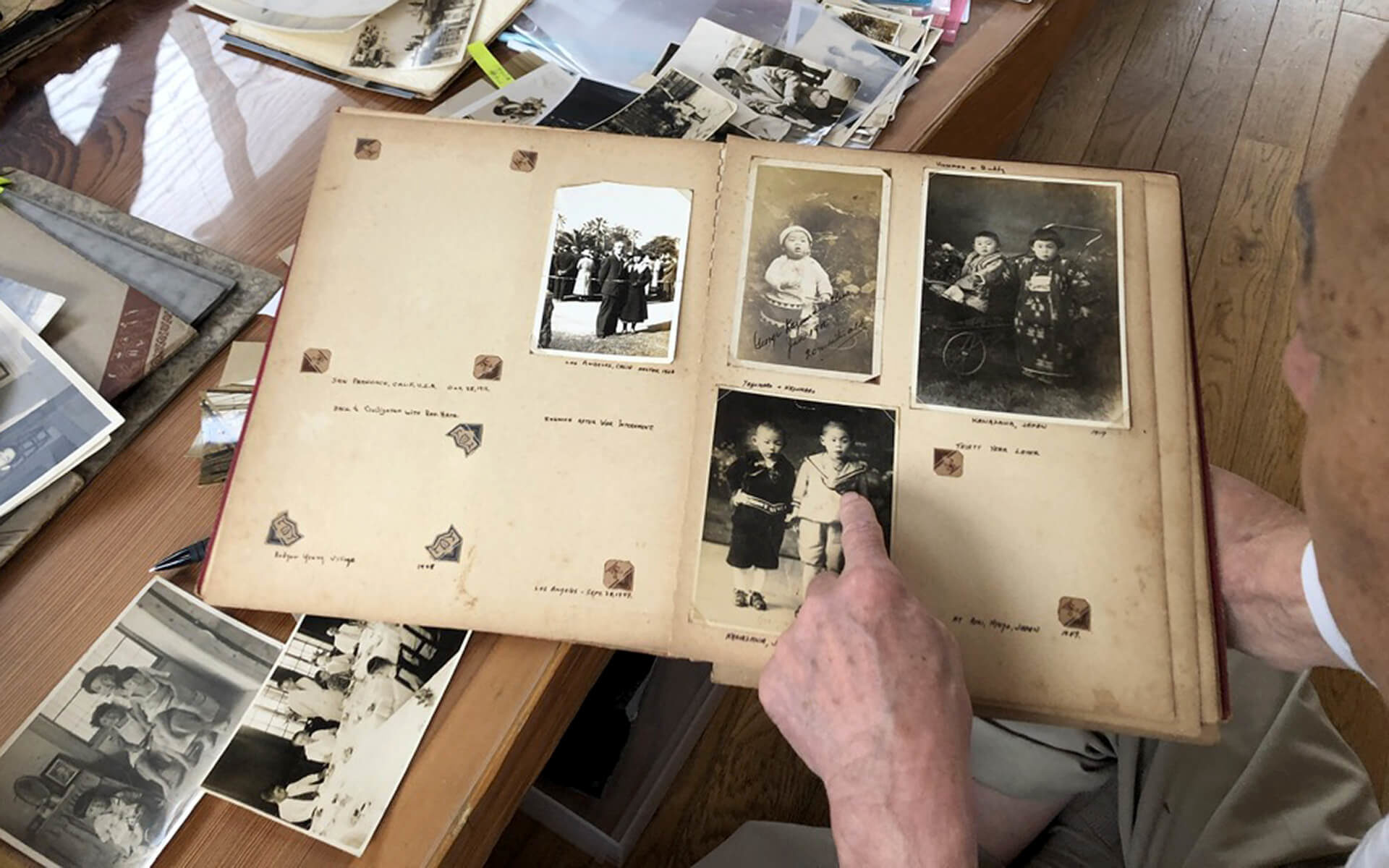

George Uno at home in Japan, looking through archives

The Producers of Asian Americans Look Back on the Making of the Documentary Series

04/22/2020

By Lauren Lola

On May 11-12, the Center for Asian American Media and WETA Television present the most comprehensive documentary series to date about the Asian American experience when Asian Americans broadcasts on PBS. Over the course of five one-hour episodes, significant moments and little-known histories are explored in the long and vastly complex history of Asian America.

Right when she joined the project, Geeta Gandbhir, producer of the fifth episode, already knew the significance the series would entail. As she elaborated, “A series about the diaspora has never been done in this way, and also there was a real focus on social justice issues. The lens of social justice was really important to this series, and that’s really important to me. A lot of the work I do in documentary focuses on social justice issues.”

“Asian American history is something I care about,” said Grace Lee, director and producer of the second and fourth episodes. “I never took Asian American studies in college, although I was a history major. It’s something I’ve always tried to learn on my own, and so I thought it would be a great opportunity to not only contribute to this landmark series, but also to go deeper into some topics that I was already inclined to be interested in.”

For some of the producers, they learned about aspects of Asian American history that they weren’t aware of before as they were working on the series. That was the case with S. Leo Chiang, producer of the first and third episodes, who initially didn’t know how the U.S. government viewed South Asians in terms of race in the early 20th century.

“I didn’t realize at one point they were seen as white and then they were flip flopping between being seen as white and nonwhite and white and nonwhite,” he explained. “And because the race was so integral to citizenship in the early 20th century that it really had huge repercussion to the South Asian American experience. So that was a totally new thing for me.”

With having five hours to tell 150 years of Asian American history, narrowing down what events to include proved to be a challenge for many of the producers. As executive producer Jean Tsien said, “How do we tell a story accurately, fairly, and not following the conventional expectations of a PBS audience? This is a once in a lifetime opportunity, and we carry the responsibility to get our facts correct and to use our archival images properly for generations to come. We’re all going to be gone one day and what’s important is what we leave behind for generations to come, so we have the responsibility to do it right.”

Other challenges the producers encountered also revolved around what era they were covering in their respective episodes. Gandbhir had the challenge of both working remotely from the East Coast and produce the “baby” of the episodes.

“But in some ways, it was also a blessing, because myself and my team were left to kind of creatively do what we wanted,” she said. “I also had an amazing story producer, Shaleece Haas, who I have to mention, who was instrumental in this because she was on the ground in LA, sort of on the front lines, demanding the attention we needed and finding stories. So that was really helpful. But I think that was just the biggest challenge, was really just being removed, not being as embedded with the team as everyone else.”

Lee had the opposite problem. While working on the second episode, which mostly covers World War II, she found herself conducting interviews with descendants of those who lived through that era.

“You really understand why it’s important to record our family’s stories while people are still alive,” she explained, “because every time another generation passes on, the story gets diluted. Fortunately, we have things like documents and photographs and things, but nothing beats having filmed images, recorded audio of people telling their stories even later on in life.”

Amidst the challenges the producers overcame working on Asian Americans, many standout moments made the experience all the more rewarding and memorable for them.

For Chiang, that came in the form of interviewing people like Tammy Duckworth and David Henry Hwang. “There were a lot of really great people that I had the privilege of speaking to and a lot of great stories that I heard,” he said. “Sometimes for the first time, sometimes it’s their stories that I’ve only read about, but now I get to hear it from the people that were connected to the source of that story.”

Lee liked seeing the evolution of the Asian American movement in the form of the Asian American Roots program at San Quentin Prison. “It was really cool to think about how 50 years ago, these 19-year-olds at [San Francisco] State were protesting just to learn the history of their communities, and then another 50 years later, people who’ve graduated from these Asian American studies programs are doing the same thing for a new generation at San Quentin,” she elaborated.

Revisiting history that has been explored by filmmakers before made for a powerful experience, as was the case of Gandbhir in revisiting Vincent Chin’s story. “Renee Tajima-Peña, who was one of our Series Producer, had done an amazing film on Chin. But to revisit it again, it is a story that never gets old. It is constantly relevant, so it was really powerful to revisit that story today,” she stated.

The fact that Asian Americans was able to happen at all is a standout to Tsien, and considers it a tribute to like-minded filmmakers who paved the way such as Loni Ding and James Yee. “There was a time when the establishments did not trust or support Asian American filmmakers to tell their own stories, and I told everyone, this series is the most important project of my life,” she said.