The West | Full Documentary

Exploring The West

Spanish, British, French, Chinese, and Russian explorers came to the West from every point of the compass. Native Americans, its original inhabitants, have lived there for so long that their stories of creation linked them to the land itself.

Clip

3m 3s

Clip

Exploring The West

3m 3s

Spanish, British, French, Chinese, and Russian explorers came to the West from every point of the compass. Native American

Full Length

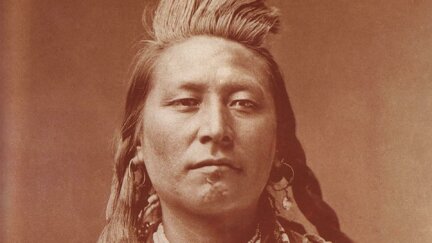

The People

82m 20s

The West begins as the whole world to the people who live there. It becomes a New World when Europeans arrive, a world sha

Full Length

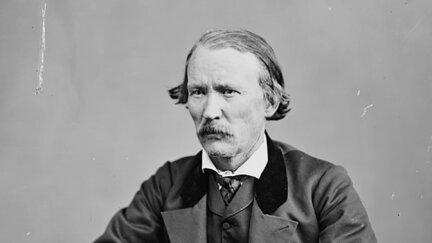

Empire Upon the Trails

84m 31s

Americans head west along many pathways -- following the fur trade into the mountains, fighting for self-determination in

Full Length

Speck of the Future

84m 49s

The Gold Rush brings the whole world to the West, as 49ers from Asia, South America and the eastern states scramble for “a

Full Length

Death Runs Riot

84m 47s

Civil war comes early to the West. In “Bleeding Kansas,” abolitionists battle for free soil. In Utah, federal troops march

Full Length

The Grandest Enterprise Under God

84m 33s

A triumph of the human spirit, the transcontinental railroad opens a new era in the West, carrying homesteaders onto the p

Full Length

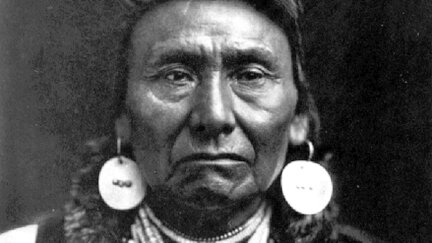

Fight No More Forever

85m 6s

The federal government tightens its grip on the West, but three bold spirits remain defiant -- Sitting Bull, who prophesie

Full Length

The Geography of Hope

84m 53s

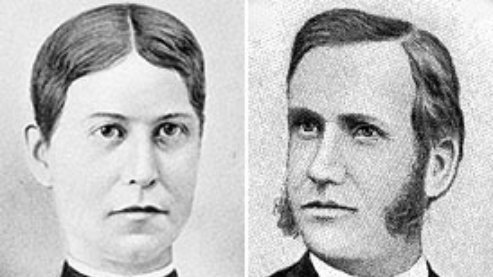

Newcomers arrive by the millions, bringing a new spirit of conformity to the West. Indian children are taught to forsake t

Full Length

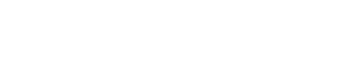

Ghost Dance

58m 38s

As settlers race to claim tribal lands, Native Americans take up the Ghost Dance, trusting in its power to restore a lost

Full Length

One Sky Above Us

62m 58s

As the 20th century neared, Americans celebrated with the World Columbian Exposition, where they were told that the fronti

Clip

The Role of Horses

4m 51s

Horses were brought to the West by the Spanish — the utilization of horses changed the way of life for Native American peo

Clip

Extraordinary Landscape

3m 42s

The West stretches from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean, from the Northern Plains to the Rio Grande — more than 2 mil

- Prev

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next

About the Film

A nine-part series chronicling the turbulent history of one of the most extraordinary landscapes on earth. Beginning when the land belonged only to Native Americans and ending in the 20th century, the film introduces unforgettable characters whose competing dreams transformed the land. It was a tragic, inspiring intersection where the best of us met the worst of us — and nothing was left unchanged.

Premiered on PBS: September 15, 1996.

Explore More

Explore Related Films

![The American Buffalo [2023]](https://d1z5o5vuzqe9y4.cloudfront.net/uploads/The-American-Buffalo/key-art-and-splash-site-materials/_250xAUTO_crop_center-center_60_none/AmericanBuffalo-ShowPoster-_sized.webp)

The American Buffalo [2023]

Examining the center of one of the country’s most mythic and heartbreaking tales.

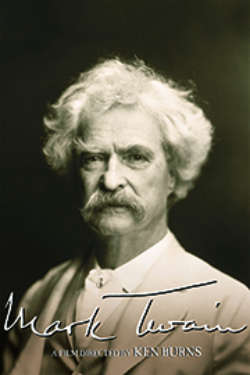

Mark Twain [2002]

"I am not an American, I am the American." The remarkable story of Samuel Clemens' adventurous life as a writer.

The National Parks: America's Best Idea [2009]

This film features those willing to devote themselves to saving land that they loved and practicing democracy.

Lewis And Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery [1998]

The remarkable tale about the Corps of Discovery who sought out the promises of unknown land.

Civil War [1990]

It was the most horrible, necessary, intimate, acrimonious, mean-spirited, and heroic conflict of the nation.

See All Films