Just as President Biden is set to meet with top European leaders, he announced the U.S. is providing more aid to Ukraine in the form of cluster munitions. The controversial weapons, banned by some 100 countries, are meant to boost Ukraine's counteroffensive against Russia. But the move is sure to upset members of Biden’s own party as he begins a critical five days on the world stage.

Clip: U.S. approves controversial cluster munitions for Ukraine ahead of NATO summit

Jul. 07, 2023 AT 9 p.m. EDT

TRANSCRIPT

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Laura Barron-Lopez: Good evening and welcome to WASHINGTON WEEK. I'm Laura Barron-Lopez. Today, President Biden announced the U.S. is providing more aid to Ukraine, this time in the form of cluster munitions. The controversial weapons banned by some 100 countries are meant to boost the Ukrainian military's slow going counteroffensive against Russia. The move is sure to upset members of Biden's own party right as he begins a critical five days on the world stage. The three-country trip could have significant consequences for the war in Ukraine and the president's own legacy. Weeks after a failed mutiny left Russian President Vladimir Putin weakened, Biden will attend a key NATO summit in Lithuania. There, he's aiming to bolster the coalition against Russia and increase the number of countries in the security alliance. Still, delicate and complicated dynamics are at play among NATO members, with Sweden's ascension to the alliance still blocked by Turkey and no clear timetable set for Ukrainian membership. Joining me to discuss this and more is David Sanger, a White House and national security correspondent for The New York Times, and here with me at the table, Susan Page, Washington Bureau Chief for USA Today, Sabrina Siddiqui is a White House reporter for The Wall Street Journal, and Margaret Talev, Senior Contributor at Axios and the director of the Institute for Democracy, Journalism and Citizenship at Syracuse University. Thank you all for being here tonight. David, I want to start with you. Let's begin with the cluster munitions announcement today by the White House, which President Biden told CNN was a difficult decision for him to make. It's controversial and it took the White House a long time come to this decision and they were reluctant about it. Why did they do it now?

David Sanger, White House and National Security Correspondent, The New York Times: Well, they did it now, Laura, in large part because the Ukrainians are getting pretty desperate. They haven't run out of ammunition right now, but they are burning off 7,000, 8,000, 9,000 rounds of artillery every single day. And the United States and its allies simply cannot keep supplying them with that level of what they call unitary munitions, in other words, an artillery round that just goes and lands in one place. But the Pentagon has been sitting for years on this very large mountain of these cluster munitions, and as you said, they are banned by treaty by well more than 100 countries, but including some of America's closest allies, Britain, France, Germany among them, who signed onto this treaty in 2008. And the reason they are banned is that they distribute a group of sort of small bomblets over several football fields worth of area. And these bomblets are basically like small hand grenades and then they go off and they can do grievous harm. And the concern is that some of them are duds and get picked up later on, frequently by children, years after a conflict is over. And you can imagine the kind of awful suffering and horrendous injuries or death that that causes. So, the administration pushed this down the road as far as they could, but they hit the moment where it was really the only option in order to keep the Ukrainians going. And the Ukrainians said they'd rather have this than lose to Russia.

Laura Barron-Lopez: That's right, the Ukrainians have been asking for these cluster munitions for a while now, Margaret. How significant is this announcement? And do you think that the political backlash here will be sustained or more muted against President Biden?

Margaret Talev, Senior Contributor, Axios: It is significant. It's a potential lifeline, or at least help, a big help for Ukraine. But also it's not what Ukraine really wants, which is NATO membership, and as President Biden heads into this NATO meeting, I'm not going to say it's a consolation prize, but it is certainly less skin in the game for the U.S. than the one sort of big help that Ukraine really wants, which is either entrance into NATO or at least a timetable to get there. Politically, on the home front for President Biden, yes, there's a group of 14 Senate Democrats who objected to this preemptively on the front end, yes, we're seeing several House Democrats coming out today, Chrissy Houlahan, who's a veteran from Pennsylvania, maybe one of the most important, but lawmakers from all over the country, Minnesota, California, saying the U.S. will lose its moral high ground. But in the White House's calculation, these cluster munitions already are being used. They're being used by Russia as well as by Ukraine. And while there is certainly the risk of collateral damage, civilian damage, thousands and thousands of civilians already have been killed. And the calculation is that this is a better protector of civilian life in Ukraine than not to give it to them.

Laura Barron-Lopez: Sabrina --

Susan Page, Washington Bureau Chief, USA Today: White House made another point, I think, that was important in the president's calculation, and that was Ukraine is going to drop these bombs on Ukrainian territory, not on foreign territory. Ukraine is going to have a huge incentive to clean up whatever duds there are once this war is over. And I think that was a persuasive argument for the White House when they considered this request.

Sabrina Siddiqui, White House Reporter, The Wall Street Journal: And that's a key point because the White House said that it did not come to this decision easily. As you noted, this has been a debate that's been ongoing for months. And in order to get to a decision, they did secure some assurances from the Ukrainians that they will not use these munitions in densely populated areas, and specifically that the Ukrainians will record the use of these munitions so that they would be able to assist in the demining effort after the war is over. The administration also was emphasizing that the dud rates for their munitions is less than 3 percent, significantly lower than that of Russia's. Worst are estimated to be about 40 percent. Now, of course, with the uncertainty of war, how much of those assurances will be met remains unclear, but it's also an acknowledgment, I think, by the administration that not only is Ukraine very quickly running out of artillery shells, but in order to continue and make gains in this counteroffensive and really move past what is largely a static battlefront, they need not just the equipment that the U.S. has already been providing, but they need new types of weapons in order to move the ball forward.

Laura Barron-Lopez: And another big part of this trip coming up for the President as he heads to the NATO summit. David, is the question of Ukraine's membership, which Margaret mentioned to NATO. What is the status of their potential membership? And you've reported that the White House has essentially been reluctant to fast track that membership. Why are they so reluctant?

David Sanger: Well, that's right, Laura. They are reluctant because they believe, first of all, no one's going to let Ukraine into NATO in the middle of an ongoing war. That would trigger Article 5 of the NATO treaty, which would bring everybody else in NATO, or could well bring everybody else in NATO, into a direct conflict with the Russians. And so far, President Biden has said we're going to help the Ukrainians but we're not going to start World War III. And that means no direct superpower conflict. Now, you could argue that with all the weapons we've provided, including now these cluster munitions, we've done everything but put our own folks into this. But what the Ukrainians want, as Margaret suggested before, is either admission or a clear timetable. And the U.S. and the Germans have made the case, how can you provide a timetable when you don't even know how long the war is going to last. And what kind of assurances would you like to have first that Ukraine is truly going to emerge from this a democratic nation? I mean, we're all and great support of them, but they do not have a long history of democracy and they are operating under martial law right now. We sort of all forget that while the war is on. The martial law was triggered, of course, by the invasion. So, it's a pretty complicated issue, and I think what everybody's trying to do is come up with some kind of wording that would help assure that President Zelenskyy comes to the meeting. He has not said yet that he would. He's obviously holding out here. And that also would indicate some pathway of how quickly they could get there. And that negotiation has been going on for months now and it's coming right down to the wire.

Laura Barron-Lopez: David, the other country whose membership to NATO is still in question is Sweden. And their membership is being blocked by Turkey and Hungary. Do you think that there will be significant progress on that at this summit next week?

David Sanger: I suspect that Sweden is going to get in, just as Finland did. For NATO, it was much more important that Finland get in quickly. They have a much superior military and obviously they have a huge contribution they make to the intelligence effort because they watch so much of the seas and have 800 miles of border with Russia. But Sweden is important as well to get into this. And those two countries, of course, have been out of NATO for a long time. I suspect at some point you're going to see President Biden and President Erdogan of Turkey meet. The fact of the matter is that the U.S. is simply not giving Turkey F-16 fighters that it wants right now. And the Congress has made it pretty clear they're going to block this unless Turkey relents. Turkey's concern is what they believe is Swedish support for dissident groups and ethnic groups that they believe are opposing Erdogan.

Laura Barron-Lopez: Margaret, looming over this entire summit is also what just played out over the last few weeks with the Wagner Group mutiny against Vladimir Putin. How much do you think that is going to be a topic of conversation as these leaders meet?

Margaret Talev: Well, for sure, on the sidelines, it will be a huge topic of conversation. I think what gets said officially at the microphones would probably be a little bit more circumspect, but it has -- on the one hand, Ukraine has had a much harder time with the counteroffensive than they'd hoped, slower progress, on the other hand, the incident with Prigozhin and President Putin certainly showed a whole lot of weaknesses and vulnerabilities on his part, and I think that will become part of the western alliance's conversations. You'd asked about politics earlier, domestic politics as well, actually. I think really at home, the Ukraine war has been much more of a wedge issue for Republicans than it has been for Democrats, and I think that helps insulate Biden. As long as there's no U.S. forces on the ground whose lives are at risk, Americans are worried about the economy, most Americans support the Ukrainians, and their red line is they don't want U.S. troops committed.

Laura Barron-Lopez: Susan, Biden is going to be giving a big speech when he's on this trip in Vilnius, in Lithuania, at the conclusion of the summit, which the White House is saying it's going to be about America's work to restore alliances and be working alongside allies. This was a bit of his 2020 pitch as well. But do you think voters are paying attention to this message that he's sending when he's abroad?

Susan Page: You know, if you think about unintended consequences, Ukraine is not going to become a member of NATO, not in the near term, but Ukraine has both pulled NATO together and given NATO a mission after a period of time when there were some questions about what was the role of this western alliance in what had become a new world order. Now, we're back to the west confronting Russia. And one of Joe Biden's fundamental appeals to voters last time around was that he was an experienced foreign policy hand with a network of contacts and an understanding of these international relationships that he could bring to bear because there was a fair amount of repair that needed to be done after the tumult and change of the Trump administration. So, I think this is going to be a big speech he makes, makes that argument that he's provided this leadership. Does it matter politically in the United States? I don't think so. If there was a war, yes. But I think Americans are glad things are going as well as they have gone in Ukraine. Certainly, we never expected this war to go on so long at the time at the original Russian invasion, but Americans care, as Margaret was saying, about what's happening at the kitchen table. Where is inflation? Does the job market keep strong? What's happening to crime in the streets? These are issues in people's daily lives.

Laura Barron-Lopez: David, before I let you go, I do want to ask you about one other big, far reaching action that's going to happen at the NATO summit, which is them -- NATO approving their first defense plan since the cold war. What is the significance of this? And, practically, what does it mean?

David Sanger: It means that they are, after experimenting, as Susan suggested, with all kinds of other missions during those 30 years of kind of false hope that Russia was going to get folded back into the Western economy, they are now coming up with a true integrated defense plan with requirements about how much money they've got to go spend. Not all of them that signed onto this. And they've also been approving, as of today, in fact, more aid to Ukraine in the amounts of hundreds of millions of dollars. I think what's worth remembering here is that Vladimir Putin has three ways to go win this war over the next year or so. One of them is if European resolve fails. The second one of them is, and I think suspect in Putin's mind, is if Donald Trump or someone with similar views ends up getting elected and pulling back the U.S. commitment. And as Susan suggested, it's really the Republicans who have suggested, some of them have, that the U.S. should not be as deeply involved. And the third way he could win is if the Ukrainians run out of ammunition, not just the munitions we were discussing, but air defenses and so forth, which the Europeans are helping provide as well. And it's really only the third item providing this for the Ukrainians that's within Europe and the president's control. And so the focus, the laser focus on making sure the Ukrainians don't lose and perhaps helping them win is going to be really the drive of this summit. It's going to be a lot harder than the last time NATO met.

Laura Barron-Lopez: David, thank you so much for joining us. I will see you over in Vilnius and for sharing your reporting with us.

!FROM THIS EPISODE

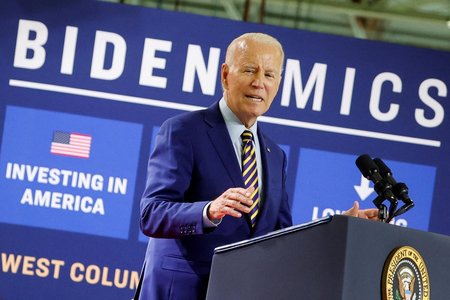

Clip: Biden touts economic policies on campaign trail as Trump and DeSantis feud again

Full Episode: Washington Week full episode, July 7, 2023

© 1996 - 2026 WETA. All Rights Reserved.

PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization