Submersibles Through Time

About 99 percent of our planet's living space lies underwater,

with a dizzying variety of organisms thriving from the surface

to the scorching waters of our deepest ocean vents miles

below. Submersibles, not surprisingly, have played a key role

in exploring and understanding this last frontier. Reaching

astounding depths and capable of performing complicated

scientific experiments, these advanced craft have even begun

to tease out clues to the origin of life and the formation of

our planet. In this time line, see just how imaginatively

these underwater dream machines have evolved over the

decades.—Rima Chaddha

|

|

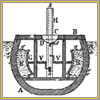

The world's first submersible (1620)

Records show that British carpenter and gunner William

Bourne designed the world's first truly submersible boat

as early as 1578, but it was not until Dutch physicist

Cornelius Drebbel modified Bourne's plans 40 years later

that the man-powered submarine finally came into

existence. Shaped like an enclosed rowboat, the vessel

included ballast tanks for stability and a system of

screws for managing the amount of water in her tanks,

enabling the submersible to sink or rise. Complete with

six oars (and 12 oarsmen) for propulsion, a snorkel-like

apparatus for air, and leather hides for waterproofing,

Drebbel's third version of this contraption could

descend to a depth of 15 feet, allowing it to travel

down the Thames River.

|

|

|

The bathysphere (1930)

While many of the world's navies have long used highly

developed submarines in military operations, scientists

began their underwater exploration with more primitive

vessels. These early manned submersibles were often

heavy, cramped metal containers, dangled like anchors

into the sea. In 1930, William Beebe (left) and Otis

Barton (right) became the first humans to observe the

deep ocean in their newly designed bathysphere, gazing

through quartz-glass portholes three inches thick. By

1934, the team reached a world-record depth of 3,028

feet, more than twice as deep as their previous dives.

|

|

|

Trieste (1953)

An untethered, deep-diving bathyscaphe (literally "deep

boat"), Trieste was the brainchild of Swiss

inventor August Piccard, who in the 1930s reached

unprecedented altitudes of almost 52,000 feet with his

unique pressurized aluminum gondola. Piccard modified

his atmospheric balloon concepts to design the

Trieste, using gasoline, which is lighter than

water, for buoyancy. In 1960, the submersible dove more

than 35,000 feet to the deepest point on Earth, the

Marianas Trench, withstanding a crushing pressure of

eight tons per square inch.

|

|

|

Alvin (1964)

As the oldest manned research submersible still in

operation, Alvin boasts an impressive

résumé. Having logged over 4,000 dives so

far, the titanium sphere was the first manned vessel to

visit the wreckage of the RMS Titanic.

Alvin has also helped researchers discover

approximately 300 new animal species, including

foot-long clams and giant red-tipped tubeworms. Thought

lost in 1968 when her support cables failed and her crew

abandoned ship, the craft spent 11 months on the

seafloor, sustaining only minor damage. Near-freezing

temperatures and a lack of oxygen kept even the lunches

left onboard perfectly preserved—if a bit damp.

|

|

|

Johnson Sea-Link (1971)

The Johnson Sea-Link class of highly maneuverable

vessels can accommodate up to four people each in dives

of as deep as 3,000 feet, but its chief claim to fame is

its use of highly specialized equipment. Using

manipulator arms, suction devices, and rotating

sample-collection tools, the futuristic

Sea-Link makes it possible for crew members to

execute from within the submersible nearly every task

once performed by divers. Equipped with sonar,

laser-aimed cameras with arc lights, and a

five-foot-wide acrylic viewing sphere, the

Sea-Link is a proven research vessel.

|

|

|

Clelia (1976)

This "yellow submarine" has a lot of sensitive equipment

on board, but she's more durable than she looks.

Clelia is designed to withstand possible tumbling

and turning in waves of up to six feet, even with a full

crew onboard, yet can be balanced underwater to provide

researchers with an exceptionally stable platform from

which to observe. Equipped with sophisticated cameras

and 500-watt metal halide lights, Clelia assisted

scientists trying to determine why the 729-foot iron-ore

carrier, the Edmund-Fitzgerald, sank to the

bottom of Lake Superior in 1975.

|

|

|

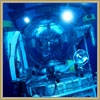

Mir I and II (1987)

Slow-moving and battery-operated, the Mir I and

II are nevertheless two of the deepest-diving

vessels in the world. Able to descend nearly 20,000

feet, they can access up to 98 percent of the world's

oceans, making them ideal for everything from research

to underwater filmmaking. In fact, director James

Cameron took advantage of the submersibles' 5,000-watt

lights when filming his blockbuster movie

Titanic. Despite stretching over 25 feet long,

each Mir has a personal sphere just seven feet in

diameter for her three-person crew.

|

|

|

Autonomous Benthic Explorer (ABE) (early 1990s)

The first underwater vehicle of her kind, the

ABE is a true robot, operating autonomously with

no onboard crew or tethers to guide her. While the

small, seven-foot-long vessel moves at a maximum rate of

just two knots, she can cover large areas of underwater

terrain as deep as 16,500 feet for months at a time, a

task that would prove prohibitively expensive if

attempted with manned or tethered machines. The

ABE is programmed to perform several tasks on her

own, such as navigating, taking photographs, collecting

data and samples, even powering down or "sleeping."

|

|

|

Deep Flight I (1996)

Don't let the name—or the look—fool you.

Deep Flight I's aeronautical-like design is ideal

for the water. Forgoing the more traditional ballast

systems used to sink and raise most submersibles, this

vessel has short, inverted wings providing the "negative

lift" needed to pull her downward at a rate of up to 12

knots. Deep Flight I is equipped to carry

high-definition and IMAX video cameras, and is designed

for deep ocean access. To operate the craft, a single

pilot lies on his or her stomach, controlling the

submersible with joysticks.

|

|

|

DeepWorker 2000 (1997)

Affectionately dubbed an "underwater sports car,"

DeepWorker 2000 is compact and relatively

lightweight at 1.3 tons. Diver Phil Nuytten (pictured

here) designed the craft to give researchers the ability

to move as freely as scuba divers yet to far greater

depths (2,000 feet). DeepWorker 2000 is

controlled by a single pilot who serves as data

collector, navigator, and camera operator. Steering the

vessel with foot pedals, the pilot performs other

tasks—such as cutting cables, lifting objects, and

operating scientific instruments—using manipulator

arms, which are jointed like human arms to allow for

freer motion.

|

|

|

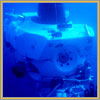

ROV Hercules (2003)

Scientists designed this remotely operated craft chiefly

to study and recover artifacts from ancient shipwrecks,

but Hercules can be used for a wide array of

scientific purposes. Armed with a flexible set of

multipurpose tools, one of the craft's two manipulator

arms offers "force feedback," allowing operators miles

away to better control the pressure the device applies

upon more delicate specimens, such as boxes found aboard

the RMS Titanic (pictured here). Equipped with a

flotation device composed of glass and epoxy resin,

Hercules can "fly" in any direction like a

helicopter and will float gently to the surface if her

thrusters stop turning, an innovation that could prove

useful for future submersibles.

|

|

|