|

|

Part 2 | Back to Part 1 NOVA: The arcades are what come to mind as one of the signatures of the Roman Empire. Why did the Romans seem to have a love affair with arcades? AICHER: The aqueducts were largely a gravity system. They had to keep the water at a certain level because if they lost that level, it was hard to get it back up again. So to maintain a slope towards the city and to bring it in at a high enough level, you had to keep the channel at a certain height. So when that channel came to a dip in the landscape they built an arcade or a bridge to take the water over it. In Rome, the long dramatic arcades occur in the five or six miles right outside of town. They built them there because the land dips down before rising again to the hills in Rome. If they had to build an aqueduct only five feet high, they would build a wall. But above that, they used the archway. This saved material. And again, arcades are not as disruptive to the landscape. A wall five miles long does damage to the transportation on the surface and creates a water barrier. Also—and I think this is important—the arch and the arcade, which is a series of arches, is beautiful. I think the Romans were as struck as we are by the beauty of the arcades curving over the landscape. In fact, some of the best villas were built to look out over the aqueducts. That was no accident. It's like landscape art. NOVA: They obviously were beautiful things. But how good were they at delivering drinkable water? Did they import water that you or I would want to drink? AICHER: On that score, I'd follow the ancient sources. They praise some water sources; others they really panned. Focusing on Rome, which I know best, there were some real stinkers. Just like Romans today, they were connoisseurs. They actually ranked them. At the top of their list was the Aqua Marcia, one of the long aqueducts that came from the springs in the mountains and traveled 60 miles. In fact, a newer aqueduct of the same name delivers Rome's most prized water today from springs in that same area. Spring water was generally cooler than stream or lake water, and cleaner, too. Another source that was highly prized was an underground aqueduct, the Aqua Virgo, which is delivered to the Trevi fountain today. Today these waters would be undrinkable if they weren't treated because the city has spread out to include Virgo's springs. Water from other aqueducts would come in muddy. Frontinus tells us of an aqueduct that tapped a lake north of Rome. He says it was a real stinker.

AICHER: They didn't use chemicals, but they had other ways. First, they used settling basins. It was like a pool. The basins would slow the water down. As it slowed, the impurities or the load, as it's called, dropped out of it. That would remove some of the sand and other impurities. We also purify water by aerating it. The water in the aqueducts was exposed to air throughout its journey, although I don't know if the Romans knew this improved the quality of their water. Instead of a settling basin, one of the aqueducts had zigzags built into it. We figure that these zigzags caused the water to slow down, which would unload impurities. Occasionally the Romans would have to shut the water off. Someone would climb into a tunnel from the surface through a well hole. There would be little hand- and footholds carved into the walls of these shafts. Sometimes they'd go down 30, 50 feet. Slaves would shovel out impurities that would be hauled to the top in buckets. NOVA: Are there still mysteries left about the aqueducts and the water distribution system that archeologists, people like yourself, are trying to understand? AICHER: There are a number of mysteries that remain. We don't know how the Romans engineered some of the tunnels or how they went about surveying a tunnel that went under a deep mountain, for example. There's still work being done on that. We also don't know, especially in Rome, much about how the distribution system worked on the local level. NOVA: What do we know about the local water distribution system? AICHER: We know that the water came into the city on a gravity system in the open air, like a stream. When it got to the city, it changed into a closed system. It did that by going into a large tank or water tower, called a castellum, typically placed at a high spot in the city. From the tanks, water would be transported through an underground system of pipes beneath the street. Water could be delivered up again to a height equal to the water level in the tank. It generally went to public fountains, baths or drinking basins, since only the very wealthy had their own private delivery pipes. We don't know much about the system of piping itself, at least in Rome. We do know that most of the pipes were made of lead in that city. This varied, however, depending on the locale. In Germany, for instance, where there was a lot of wood, pipes were made out of wood. Elsewhere they might be terra-cotta. NOVA: Did they have no sense, then, for the dangers of lead? AICHER: Actually, they did. At least Vitruvius did. He makes his point by saying, "Hey, look at the people who make these lead pipes!" Apparently, these workers weren't in the best of health.

AICHER: Not much. The Romans did use lead in their pipes. However, two things about the Roman water supply mitigated the unhealthy effects of lead. The first is that the water in the Roman aqueducts rarely stopped running. They had shut-off valves, but they didn't use them much. The water was meant to move. It would flow into a fountain or a basin. Overflow would pour into the gutter and then flush the city. Today, if you have lead pipes, they tell you to let the water run for awhile before you drink it. That prevents water from sitting in the lead pipes and becoming contaminated. That flushing out happened naturally in the Roman system. Secondly, a lot of the water, especially in Rome, was hard water. It had lots of minerals in it that would coat their pipes. We often use filtration systems to take some of the minerals out. The Romans didn't have that, so these minerals would encrust and coat the inside of the pipe. That layer of minerals served as a buffer. In fact, the aqueduct channels would gradually accumulate these deposits. Periodically, they would have to chip out all the encrustations. NOVA: Would the bath that NOVA built have been supplied by aqueduct water? AICHER: It's very possible, although a smallish bath like the one NOVA built could be run with water from a nearby stream or well. The huge baths, such as the famous ones in Rome, could not have been operated without the aqueducts. Some of the baths were supplied with water from private branch lines, sub-aqueducts really, that detached from the main aqueduct. NOVA: The water distribution system sounds extremely sophisticated, especially considering this was 2,000 years ago. Did the water cost people or was it a part of what the Roman state gave gratis to its people? AICHER: Both. Rome may be something of an anomaly, but it had so much water that many private users would get a grant from the emperor during imperial times. They didn't have to pay; it would be an act of patronage. However, others, such as industrial users, would have to pay. Most people would get their water from street basins, where the water was free. Pompeii probably has the best preserved distribution system. Its basins are fairly regularly spaced, so that most people didn't have to walk more than about 150 feet to get water. Admittedly, they had nothing so convenient as tap water in a fourth-floor apartment. Peter Aicher is now working on a guidebook to Rome that uses classic Greek and Roman descriptions of that ancient city, including its aqueducts.His book "Guide to the Aqueducts of Ancient Rome" was published by Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc. in 1995. A Day at the Baths | Construct an Aqueduct | Watering Ancient Rome NOVA Builds a Bath | Real Roman Recipes | Resources | Transcript Medieval Siege | Pharaoh's Obelisk | Easter Island | Roman Bath | China Bridge | Site Map Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

The arcades make up only a small percentage of the

Roman aqueducts, but they are among its most memorable

components.

The arcades make up only a small percentage of the

Roman aqueducts, but they are among its most memorable

components.

Aqueduct water was exposed to air and that helped to

clean it.

Aqueduct water was exposed to air and that helped to

clean it.

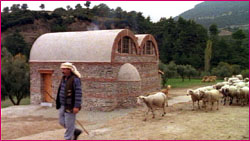

The NOVA bath, built in Turkey, is similar to private

baths built in the homes of wealthy Romans.

The NOVA bath, built in Turkey, is similar to private

baths built in the homes of wealthy Romans.