|

|

Netherlands: Problem

This image could have been taken in Katrina's wake, but it was

actually captured more than a decade ago and an ocean away

from Louisiana. Periodic flooding has plagued the Netherlands

since the Middle Ages. Half the country, including Amsterdam

and Rotterdam, lies below sea level in a drainage basin for

three rivers and at the door of the North Sea. A catastrophic

flood in 1953 killed nearly 2,000 people and destroyed whole

villages; afterward, the Dutch vowed never again.

|

|

|

Netherlands: Solution

Dutch engineers finally completed their country's

sophisticated flood defenses in 1997. The result is an $8

billion system of enormous, computer-operated dams and sea

surge barriers. The system is admired around the world as an

engineering marvel. The floodgates, parts of which are seen

here, remain open ordinarily, allowing river water to flow

into the sea, but they are quickly lowered during storms.

Built to withstand the kind of tremendous flood estimated to

occur only once in 10,000 years, the gates have so far done

their job successfully.

|

|

|

St. Petersburg: Problem

St. Petersburg, Russia is one of the most fabled of

waterlogged cities. Its battles with flooding have been

immortalized for centuries in Russian art (such as in this

painting) and in literature. The city was built atop a swamp

fed by the Neva River and the Gulf of Finland. Each fall and

winter, strong winds and ice block the flow of the Neva into

the Gulf, causing the river level to rise and, at least once a

year, spill excess water into the city. Over the years,

several disastrous floods, including the two largest in 1824

and 1924, have left considerable death and destruction in

their wake.

|

|

|

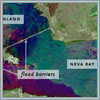

St. Petersburg: Solution

In 1980, the Soviet government began to erect a pair of

massive storm surge barriers on either side of a small island

in the Neva. With the project nearly 65 percent complete,

financial problems and environmental concerns brought it to

halt less than 10 years later. But in 2003, with new foreign

funding and a plan to keep the river healthy, the project was

revived. Construction is now under way to finish the barriers,

seen here, which will shut during storms and hopefully spare

St. Petersburg any more high-water floods.

|

|

|

London: Problem

Londoners are characteristically blasé about their

flood-prone city, but the tidal Thames River, which carves

through its center, has a history of severe flooding. The

threat of high tides has increased over time due to a slow but

continuous overall rise in the river's water level, which

experts attribute to climate change and the gradual settling

of the city.

|

|

|

London: Solution

In the 1970s, the so-called Thames Barrier, seen here, was

built across the river to protect London from the kind of

disastrous flooding that last occurred there in 1953 (when

Holland also flooded) and took over 300 lives. But scientists

say that the defense the barrier provides is gradually

declining, and it may not be able to continue to block rising

tides past the year 2030. Officials have charged a commission

with finding a longer-lasting solution, and a proposal is

under consideration to build a more extensive, 10-mile gated

barrier along the Thames.

|

|

|

Venice: Problem

Venetian scenes like this one have become almost as

representative of the city as its gondolas and elegant

architecture. The ground on which Venice lies is famously

sinking. This, combined with rising sea levels and periodic

storms that cause the Adriatic Sea to flood Venice's lagoon,

creates a phenomenon known as acqua alta, or high

water—in other words, flooding. Venetians have dealt

with the rising water for centuries by raising the level of

floors in buildings and the pavement along city canals, but

powerful storms can still prove destructive.

|

|

|

Venice: Solution

This mobile flood barrier embodies the most substantial

engineering aspect of the proposed solution to flooding in

Venice. It is part of a multibillion-dollar series of 78 metal

gates that will rise off the seafloor at the three entrances

to Venice's lagoon whenever acqua alta is forecast,

blocking the Adriatic until high tides subside. This project

has been controversial, with many experts concerned for the

environmental health of the lagoon and advising against what

may be only a relatively short-term solution. But the gates

are slated to be completed in 2011.

|

|

|

San Antonio: Problem

Texas is one of America's most flood-vulnerable states. Severe

rains can cause water to rise across dozens of counties

quickly and simultaneously, destroying homes and highways and

threatening the downtown areas of major cities such as Houston

and San Antonio. In 2002, as much as two feet of rain fell on

southeastern Texas in a week, flooding three major river

systems along the Gulf of Mexico and inundating highways such

as this one outside of Houston.

|

|

|

San Antonio: Solution

Experts consider San Antonio's anti-flood approach among the

most innovative solutions to flooding in any metropolitan

area. Between 1987 and 1996, federal and local governments

funded the construction of a 16,200-foot concrete

flood-diversion tunnel beneath the city. It siphons rainfall

out of populated areas and carries it to the San Antonio

River. Fully 24 feet in diameter, the tunnel was dug with a

massive tunnel-boring machine, seen here in action beneath San

Antonio.

|

|

|

New Orleans: Problem

Immediately after Katrina—and even

before—officials began brainstorming new flood

protection infrastructure. Tailor-made for New Orleans, it

would replace or bolster the city's existing levees. It's

still too soon to know what the plan will be, but in hundreds

of television appearances, radio interviews, lectures, op-ed

articles, and scientific papers, the experts have weighed in

with a wide range of ideas, from aggressively restoring

Louisiana's naturally defensive delta and saltwater marshes,

to mobile floodgates, to high-tech, electronically sensitive

levees.

|

|

|

New Orleans: Solution

One new idea for New Orleans was already in development before

Katrina. Construction has begun on a sophisticated hurricane

floodgate that would close across the Harvey Canal in the

event of a storm surge. The $36 million floodgate will protect

250,000 people in the West Bank area of New Orleans, which was

relatively unscathed by Katrina, from another storm. When the

new barriers are finished, they will be the first

hurricane-specific canal barriers of their kind in New Orleans

and most likely the first new flood proofing in the city since

Katrina.

|

|

|