The Conquest of Cold

by Tom Shachtman

Refrigerated railroad cars played a fateful role

in the final subjugation of native cultures in the American

West.

Artificially produced refrigeration has been the least noted

of the three technological breakthroughs of great significance

to the growth of cities that came to the fore between the

1860s and the 1880s. More emphasis has been given to the role

played by the elevator and by the varying means of

communication, first the telegraph and later the telephone.

The elevator permitted buildings to be erected higher than the

half-dozen stories a worker or resident could comfortably

climb; telegraphs and telephones enabled companies to locate

managerial and sales headquarters at a distance from the

ultimate consumers of goods and services.

Refrigeration had equal impact, allowing the establishment of

larger populations farther than ever from the sources of their

food supplies. These innovations helped consolidate the

results of the Industrial Revolution, and after their

introduction, the populations of major cities doubled each

quarter century, first in the United States—where

technologies took hold earlier than they did in older

countries—and then elsewhere in the world.

An index of civilization

A spate of fantastic literature also began to appear at this

time; in books such as Jules Verne's

Paris in the Twentieth Century, set in 1960, indoor

climate control was mentioned, though its wonders were not

fully explored. From the mid-19th century on, most visions of

technologically rich futures included predictions of control

over indoor and sometimes outdoor temperature.

In addition to flocking to cities for jobs, Americans also

became urbanites in the latter part of the 19th century

because there seemed to be fewer hospitable open spaces into

which an exploding population could expand. Large areas of the

United States were too hot during many months of the year to

sustain colonies of human beings; these included the Southwest

and parts of the Southeast, with their tropical and

semitropical climates, deserts, and swamps. Looked at

in retrospect, the principal limitation on people settling in

those areas was the lack of air-conditioning and home

refrigeration.

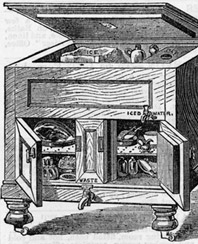

In the second half of the 19th century, the use of cold in the

home became an index of civilization. In New York, 45 percent

of the population kept provisions in natural-ice home

refrigerators. It was said in this period that if all the

natural-ice storage facilities along the Hudson River in New

York State were grouped together, they would account for seven

miles of its length. Consumption of ice in New York rose

steadily from the 100,000 tons-per-year level of 1860 toward a

million tons annually in 1880. But while the per capita use of

ice in large American cities climbed to two-thirds of a ton

annually, in smaller cities it remained lower, a quarter of a

ton per person per year.

Ice age

When New York apple growers felt competitively squeezed by

western growers who shipped their products in by refrigerated

railroad car, they hired experts to improve the quality of

their own apples. A specialist was hired to help prevent blue

mold, a disease affecting oranges, so that California's

oranges would be more appealing to New York consumers than

oranges from Central and South America.

Believing there were not enough good clams to eat on the West

Coast, the city fathers of San Francisco ordered a

refrigerator carload of eastern bivalves to plant in San

Francisco Bay, founding a new industry there. Commenting in

1869 on the first refrigerated railroad-car shipment of

strawberries from Chicago to New York,

Scientific American predicted, "We shall expect to see

grapes raised in California and brought over the Pacific

Railroad for sale in New York this season."

The conventional view is that the "iron horse" finally killed

off the "red man"; but one could with as much justification

say that it was the refrigerator.

The desire for refrigeration continued to grow, almost

exponentially, but the perils associated with using sulfuric

acid, ammonia, ether, and other chemicals in vapor compression

and absorption systems remained a constraint on greater use of

artificial ice, as did the high costs of manufacturing ice

compared with the low costs of what had become a superbly

efficient natural-ice industry.

Artificial refrigeration finally began to surpass natural-ice

refrigeration in the American West and Midwest in the

mid-1870s. In the space of a few years, as a result of the

introduction of refrigeration, hog production grew 86 percent,

and the annual export of American beef (in ice-refrigerated

ships) to the British Isles rose from 109,500 pounds to 72

million pounds. Simultaneously, the number of refrigerated

railroad cars in the United States skyrocketed from a few

thousand to more than 120,000.

The rise of refrigeration

Growth of the American railroads and of refrigeration went

hand in hand; moreover, the ability conveyed by refrigeration

to store food and to transport slaughtered meat in a

relatively fresh state led to huge, socially significant

increases in the food supply, and to changes in the American

social and geographical landscape.

"Slaughter of livestock for sale as fresh meat had remained

essentially a local industry until a practical refrigerator

car was invented," Oscar Anderson's 1953 historical study of

the spread of refrigeration in the United States reported. And

because refrigeration permitted processing to go on

year-round, hog farmers no longer had to sell hogs only at the

end of the summer, the traditional moment for sale—and

the moment when the market was glutted with harvest-fattened

hogs—but could sell them whenever they reached their

best weight.

In Great Britain, the Bell family of Glasgow, who wanted to

replace the natural-ice storage rooms on trans-Atlantic ships

with artificially refrigerated rooms that could make their own

ice, sought advice from another Glaswegian, Lord Kelvin. Lord

Kelvin assisted the engineer J. Coleman in designing what

became the Bell-Coleman compressed-air machine, which the

Bells used to aid in the transport of meat to the British

Isles from as far away as Australia. Because of refrigeration,

every region of the world able to produce meat, vegetables, or

fruit could now be used as a source for food to sustain people

in cities even half a world away. Oranges in winter were no

longer a luxury affordable only by kings.

A fateful association

Refrigeration in combination with railroads helped cause the

wealth of the United States to begin to flow west, raising the

per capita income of workers in the food-packing and

transshipment centers of Chicago and Kansas City at the

expense of workers in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

Refrigeration enabled midwestern dairy farmers, whose cost of

land was low, to undercut the prices charged for butter and

cheese by the dairy farmers of the Northeast. Refrigeration

made it possible for St. Louis and Omaha packers to ship

dressed beef, mutton, or lamb to market at a lower price per

pound than it cost to ship live animals, and when the railroad

magnates tried to coerce the packers to pay the same rate for

dressed meat as for live animals, the packers built their own

refrigerated railcars and forced a compromise.

The enormous jump in demand for meat, accelerated by

refrigerated storage and transport, spurred ranchers and the

federal government to take over millions of acres in the

American West for use in raising cattle. This action brought

on the last phase of the centuries-long push by European

colonizers to rid America of its native tribes, by forcing to

near extinction the buffalo and the Native American tribes

whose lives centered on the buffalo. The conventional view of

American history is that it was the "iron horse" that finally

killed off the "red man"; but one could with as much

justification say that it was the refrigerator.