Sheldon Jackson's Life & Legacy

The curator of the Sheldon Jackson Museum in Sitka, Alaska, discusses the life and legacy of this highly influential — and controversial — figure in Alaska's history during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

May 20, 2024

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE:

- Sheldon Jackson’s legacy remains deeply divisive, with some praising his preservation efforts and others condemning his role in cultural suppression.

- Through federal and religious authority, Jackson shaped Alaska’s educational and collecting landscape, leaving behind a museum and a trail of controversy.

- Critics and scholars alike debate whether Jackson’s actions were driven by conviction, colonialism, or both—underscoring the complexity of his impact on Alaska Native life.

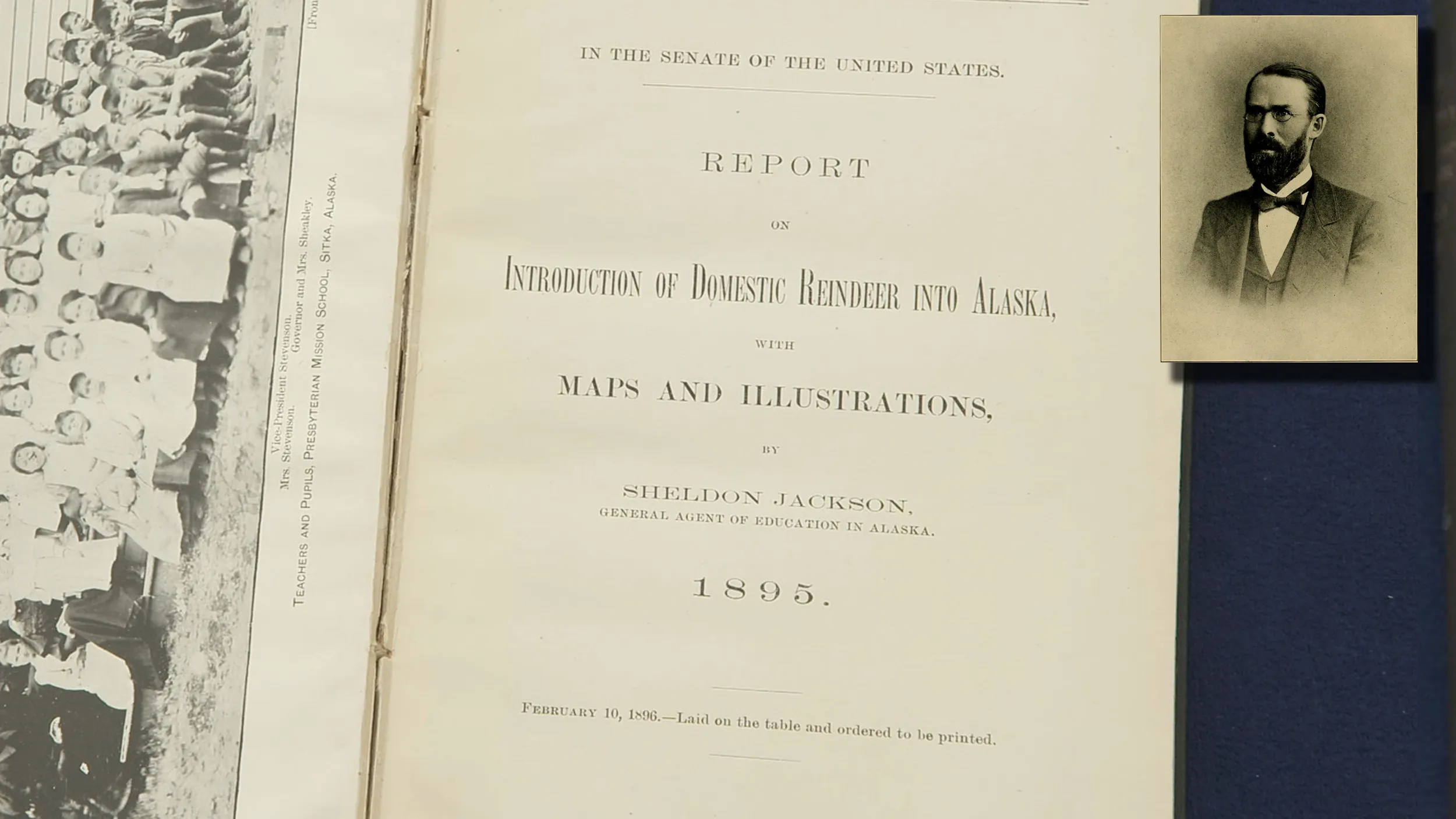

SHELDON JACKSON was a Presbyterian missionary, founder of missions, boarding schools, and churches, collector, fundraiser, and publisher of religious newspapers. He was Superintendent of Missions to the Presbytery and General Agent of Education in Alaska and used his positions within the federal government and church to establish assimilative boarding schools in Alaska, and collect, and introduce reindeer to the territory. These three seemingly disparate activities were inseparably interwoven throughout his career. A controversial figure, he has been condemned and condoned for his impact on the history of Alaska, and particularly Alaska Native peoples, but he has also been called a man of his time whose philosophy was typical and representative of widespread American 19th century values, ideals, social mores, and ideas about “science and progress.” Regardless of one’s opinion of Jackson, his work had great implications for the history of Alaska.

Sheldon Jackson was born in Minaville, New York in 1834 to Samuel Clinton Jackson and Delia Sheldon and religion played a role in his life from the very beginning. He was largely raised in Esperance, New York, where his family “experienced a religious awakening somewhat akin to today’s ‘born again Christians.’” His parents became determined their son would grow up to work for the Presbyterian Church in which they had become active. After attending a Presbyterian preparatory school in Haysville, Ohio, Jackson went to attend Union College in Schenectady. In 1853, he made his public confession of faith and pronouncement of his plan to work as a missionary. He went on to attend Princeton Theological Seminary, a hotbed of missionary furor where he met many young men and women who had worked in the field proselytizing. The “Great Awakening of 1857” happened during his final year of studies.

Shortly after graduating, Jackson married Mary Voorhees, started teaching out West, and then began to work the Board of Home Missions, commencing his missionary career. Six weeks after the wedding, Jackson and his new wife went to the Choctaw Reservation in Spenser, Oklahoma where he was assigned to teach children. His time in Oklahoma was short lived. He resigned from his position in 1858, telling his parents that he wanted to preach and not teach. In August of 1859, he transferred to La Crescent, Minnesota, to work as a home missionary in the town and vicinity. While there he began setting up churches and travelling and ministering to people as much as possible. Jackson would go on to establish over a hundred churches and preach in Minnesota, the Rocky Mountains, and the Southwest, where he first developed an interest in collecting. He also founded two missionary newspapers — The Rocky Mountain Presbyterian, and much later, the North Star in Sitka, Alaska.

Move to Alaska

Jackson first came to Alaska with the intention of Christianizing and assimilating Alaska Natives in 1877. He had read a letter written by a soldier who had been stationed at Ft. Wrangell in Alaska, requesting his Commander, General Howard, use his influence to have someone send missionaries to Alaska. 1 Soon after, Jackson reconnected with an old friend and fellow Presbyterian missionary, Amanda McFarland. Without any consent from the Presbyterian Board of Home Missions, Jackson and McFarland departed for Alaska to explore options of setting up a mission station at Wrangell. It was only the beginning of Jackson’s Alaskan missionary endeavors.

Between 1879 and 1881, Jackson visited Alaska to establish schools, churches and missions in "Sitka, Kodiak, Karlisk, Unga, Texikan, Cape Prince of Wales, and Point Barrow." 2 In 1883, he officially became the superintendent of all missions in Alaska for the Presbyterian Board of Home Missions and in the spring of 1885, was selected to be the Federal Agent of Education for Alaska, a position that made him responsible for the education of all Alaskan children.

Jackson continued to work to draw attention to Alaska and to fundraise for education in Alaska. He published many newspaper articles on the subject and gave public addresses all over the East Coast’s major cities to generate interest. He tirelessly lobbied among religious and political leaders for private and Congressional funds for education. By 1885, his efforts paid off. Congress began to appropriate money towards mission schools, and schools began operating under contract with the federal government. Jackson used appropriations to pay for teacher salaries, traveling expenses, equipment, supplies, and for the construction of new school buildings.

The Protestants Divide Up Alaska

At some point in the mid-1880s, at the invitation of Jackson, a meeting of four or five main Protestant denominations, including the Methodists, Baptists, and Episcopalians, occurred. At the meeting, three secretaries and Jackson gathered around a table to divide Alaska, culminating in a most significant event creating the Comity Plan or Jackson Polity. In his book Sheldon Jackson, Robert Laird Stewart described the meeting quoting an account by Dr. M. Henry Field:

“…[T]his little company, meeting in an upper room, was sufficient to inaugurate a policy of peace, that if adopted on a larger scale, would work for the benefit of all Christendom. And now I see the four heads bending over the little table, on which Sheldon Jackson had spread out a map of Alaska…the allotment was made in perfect harmony. As the Presbyterians had been the first to enter Southeastern Alaska, they all agreed that they should retain it, untroubled by any intrusion. By the same rules, the Episcopalians were to keep the valley of the Yukon, where the Church of England [Anglican] following in the track of the Hudson Bay Company, had planted its mission forty years before. The island of Kodiak, with the adjoining region of Cook’s Inlet, made a generous portion for the Baptists Brethren; while to the Methodists were assigned the Aleutian and Shumagin islands. The Moravians were to pitch their tents in the interior – in the valleys of the Kusko Kwim [sic.] and the Nushagak; while the Congregationalists mounted higher to the Cape Prince of Wales, on the American side of Bering Strait; and last of all, as nobody else could take it, the Presbyterians went to Point Barrow.” 3 This plan and meeting, as Maria Shaa Tlaa Williams noted, “although it appears to have been a small gathering, had great impact on Alaska, still felt today,” and it laid the scaffolding for the establishment of missions and boarding schools throughout the territory. 4

Sheldon Jackson's Museum & Mission Schools

Eighteen-eighty-seven was another pivotal year in Jackson’s career and marked the beginnings of what would eventually become the Sheldon Jackson Museum. Jackson founded the organization after touring Southeast Alaska with a group of scientists and academics. The group had visited the Sitka Industrial Training School, the boarding school that Jackson had founded along with John Brady, and thereafter, several men including President D.C. Gillman of Johns Hopskins University, Professor Dyer of Cambridge University, and Mr. Edward Hale Abbott of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, recommended he begin “an organization in Alaska for scientific investigation.” Thus the “Alaskan Society of Sitka” or the “Alaskan Academy of Sciences and Museum of Ethnology” was begun.

Jackson envisioned two societies. The first organization would meet twice a month to hear scientific papers and the second, connected to the Sitka Industrial Training School, would be an organization responsible for the objects to be collected. On October 24, 1887, he convened the first meeting, and the organization adopted a constitution signed by attending members. In the spring of 1888, the two original organizations became incorporated into one and by November, had become officially named the “Society of Alaskan Natural History and Ethnology.” Papers continued to be presented, but according to Rosemary Carlton, “collecting became the main focus … with members bringing in ‘curios’ from Native groups, the Russian colonizers, plant, animal and mineral specimens, and virtually all things loosely or otherwise connected with Alaska, including objects from the crumbling Lutheran Church.” 5

The Society of Alaskan Natural History & Ethnology’s purpose, according to the organization’s Constitution, was “to collect and preserve in connection with the Sitka Industrial Training School specimens illustrative of the Natural History and Ethnology of Alaska and publications relating thereto” and according to Jackson in a letter to Edwin Hale Abbott dated October 19, 1887, “to provide and have on hand for study by the students the best specimens of the old work of their ancestors.” 6

In December of 1889, two years after founding the Society of Alaskan History and Ethnology, the first museum building was opened in an American one-room frame house with characteristics of a Northwest Coast community house, including totemic designs painted on the front and sides of the building by Edward Marsden, a Tsimshian Industrial Training School student and later, Presbyterian minister. Even at the time of its inception, the museum building was full of totem poles, argillite, Yup’ik and Inupiaq garments, natural history specimens, and Russian artifacts lining the walls from floor to ceiling.

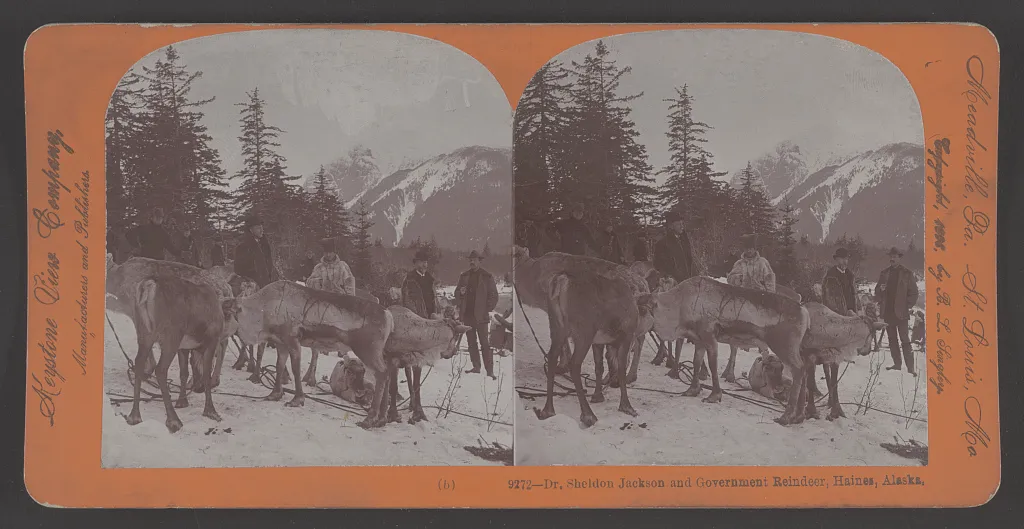

Beginning in 1890, Jackson began looking north to Point Barrow and to the southwestern area of Alaska to extend his mission school system. He interwove the introduction of reindeer into his plans, a process that enabled him to simultaneously encourage assimilation of indigenous peoples by pushing them towards working in a cash-based economy and provided him with opportunities to collect from those whose cultures he was seeking to change. From 1890 until 1902, he made an annual tour of inspection into Southwestern Alaska and the Arctic Coast, travels made possible by transport via the ships of the Revenue Cutter Service during the annual Bering Sea Patrol. The Patrol oversaw patrolling of the whaling fleet and preventing the smuggling of whale bone, protected sealing grounds from poachers, enforced revenue laws, acted as travel lifesaving stations for shipwrecked boats, and sought to inhibit the importation of alcohol. Acting secretary of the treasury, George S. Blatchelly, directed the leadership of the Patrol to transport Jackson to places “in the discharge of his official duties.” As a result, the ships transported Jackson, his teachers, and their supplies, assisted in building schools, and loaded, packed, and unloaded thousands of artifacts for Jackson.

While visiting villages in the Bering Sea, Jackson saw and heard reports of indigenous peoples who were facing food shortages because of increased hunting by whalers and sealers in the area. Jackson documented the food shortages and conditions he saw when he wrote narratives of his travels for religious and secular journals. He wrote of the shortage of seal, walrus, fish, aquatic birds, reindeer, and whale. He compared the slaughtering of herds of buffalo for their pelts in the West to the relentless hunt of whales for their fat and bone. He described the walrus, having been hunted for their tusks by whalers for commerce as being “practically extinct” and described sea lions and seals in the Bering Sea as “rare.” 7 The supply of reindeer, he wrote, had been “killed off or frightened away to the remote and more inaccessible regions in the interior.” 8 He described seeing deserted villages and witnessing slow starvation.

A visit to Siberia during a patrol trip of the Revenue Cutter Bear captained by Michael Healy took place in the summer of 1890. While visiting the indigenous Koriaks, Jackson and Healy observed that they had domesticated reindeer, which provided them with food, hides, bone and antlers. The two men, inspired by what they saw, developed a plan to introduce domestic reindeer to Alaska, a project that would allow Jackson to set up agricultural schools to train in herding and extend his reach and influence and give him an opportunity to collect. Although federal funding was not originally forthcoming for the project, Jackson secured permissions to fundraise through the Church. Federal financial support was not made available for the reindeer work until 1894 and Jackson continued to oversee the program until 1906, spending his summers on board the Revenue Service cutters, inspecting reindeer herd and schools throughout Alaska. 9

Accounts of Jackson’s reindeer projects were written in his annual Report of the Commissioner of Education and in his lengthy reports entitled “Introduction of Domesticated Reindeer into Alaska.” The reports have detailed daily accounts of Jackson’s itineraries and reports from managers of the Teller Reindeer Station and official documents and correspondence relevant to the reindeer project. He submitted annual reports to Congress for the U.S. Department of the Interior from 1891 through 1905 with the final report published in 1908.

Jackson, like Edward Nelson, found that “curios” were easily obtainable from a people eager to trade their “good for nothing things” for metal pots and pans, tools, tobacco, fabric, lead and powder, Pilot bread, and other novelties.” 10 Most of what he collected on these trips ended up at the Sheldon Jackson Museum but some were sold to raise money for purchasing reindeer, given as gifts to supporters of the museum, or became part of Jackson’s educational exhibits to help him fundraise for and promote his efforts in Alaska, including his museum in Sitka. Some of what he collected around this time was sent to the Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Jackson was involved in many “world’s expositions” and helped collect or had items he collected displayed at numerous public events. Such expositions sought to showcase the achievements of nations and focused on trade, technological advances, and showcased popular ideas about cultures and social progress. Although records on Jackson’s involvement and contributions to expositions are spotty or in some cases, non-existent, we know he was involved in or was asked to contribute to the World’s Industrial and Cotton Exposition in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1883/94, the American Exposition in London in 1886, the Buffalo International Fair Association in 1888, the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893-94, the International Exposition in Mexico City in 1896 (perhaps just via honorary title), the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska in 1898, the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York in 1901, and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904. It is possible that some of the Omaha Nebraska 1898 Collection which had been sold to the Bureau of Education and included some of Jackson’s personal collection. Some of the pieces sent to the Columbian Exposition became the foundation for the collection of the Field Museum in Chicago. Works from Industrial Training School students ended up in the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle, Washington in 1905-1910 and ended up being transferred to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Collecting for these numerous expositions was part of Jackson’s marketing effort to draw attention to his efforts in Alaska and gain moral and financial support for his work for the federal government and Presbyterian Church. Jackson was undoubtedly motivated to collect for such expositions to draw attention and he hoped, garner support for, his work in Alaska.

Jackson continued to use his trips to the Arctic to collect for the museum in Sitka and by September of 1893, the collection had grown to over 5,000 objects and Society members were struggling to find places to store artifacts. With little room left in the one-room wooden building, Jackson began to aggressively fundraise and campaign for a new museum. He donated his own funds and solicited money from supporters of the Society over the course of several years. In 1895, construction on a new museum building to house the ever-growing collection began. Jackson sought out John G. Smith of Boston, a building contractor and devout Baptist and supporter of Christian missions, and architect Charles Geddes, for assistance and plans for an octagonal, fireproof, concrete building with a glass cupola on top were drawn. The new museum, completed in 1897, with assistance from Sitka Industrial Training School students and Jackson’s friend and Tlingit interpreter William Wells, was the first concrete building in Alaska. It still houses the Sheldon Jackson Museum.

While Jackson was the primary collector for the Sheldon Jackson Museum and did the majority of collecting between 1890 and 1895 himself, he used his federal government and church positions to help him draw upon the support of teachers, missionaries, and friends to acquire objects for him. Though Jackson had collected in Southeast Alaska early on, he shifted his focus largely to the Arctic and Bering Sea regions with the reindeer project. By the early 1890s, Jackson had a reputation as a collector and founder of the Alaska Society of Natural History and Ethnology and traders and Revenue Cutter men were regularly giving artifacts to him that they had purchased, traded, found or taken from gravesites — a practice completely unacceptable by modern standards. 11 Captain Healy and his wife and men working for him in the Revenue Cutter Service often gave objects, including sled bags, leather and gut pouches, natural history specimens, and utilitarian objects.

Jackson's Methods and Motivations

Jackson collected by “acceptable standards of the 19th century and in a relatively sensitive manner,” but neither his or his colleagues’ methods and documentation of collecting would measure up to today’s museum practices and leaves us with many unanswered questions. 12 While Jackson inscribed many objects he collected in later years with his name, date of collection and place of collection, he sometimes wrote his name and dates upon pieces he had not himself collected. He sometimes sent shipments to the museum with minimal information, a practice illustrated in a letter he wrote to Alfred Docking March 17, 1892. In the letter, Jackson beseeched him that when boxes of curios arrived, he “had better leave them to be opened when I can be with you, as the things are not labeled … the boxes and packages are numbered and I have a list of the places where they were obtained corresponding with those numbers.” 13

As was typical of 19th-century collectors, Jackson and his counterpart collectors frequently omitted important details about their collecting. They rarely noted the names of the makers of objects and they often failed to specifically detail how they acquired what they collected. Carlton wrote “…random collecting and shipping of artifacts by Jackson’s missionaries and teachers contributed greatly to the quantity of artifacts found in Sheldon Jackson’s collections around the country; unfortunately, it also contributed to the modern curator’s nightmare of undocumented objects. … Many of the people he had collecting for him never adopted even the rudimentary practice of writing location, date, collector or use on the object.” 14

Although specific details about transactions in which Jackson acquired objects is not always available in object records or meeting minutes of the Alaskan Society, there are, as cited by Carlton, some examples of correspondence and travel diaries written by him offering some details. During an Arctic summer tour of 1891, for example, Jackson had made arrangements for collections to be made at Haines, Yakutat, Jackson, Cape Prince of Wales, Point Hope and other areas, with the idea of picking them up the following summer or having them shipped for transport to Chicago for the Columbian World’s Fair Exposition. Jackson wrote about having “left Pilot bread, lead, tobacco, axes, kettles, drills, saws, mirrors and assorted other materials to be traded for ‘curios’” and asked teachers to pay for materials out of their own pocket with reimbursement coming later, and he traded personally with the Natives.” 15 At other times, the General Agent instructed his teachers to “get the ‘curios’ but left them with no financial means with which to acquire them. 16

Jackson differs from many of his counterpart collectors of his day because he was interested in preventing Alaskan material culture from leaving Alaska and because he saw value in collecting utilitarian items used on a day-to-day basis and objects that were readily available for sale in tourist shops. The first objects he purchased for the collection included nearly two dozen Haida argillite pieces from a shop in Metlakatla and Victoria, British Columbia. He also sought out Northwest Coast silver souvenir spoons, basketry, covered bottles, beaded covered baskets, spruce root trivets and doll hats, argillite sculptures and pipes, walrus ivory cribbage boards, napkin rings, and buttons. Unlike many collectors of his time, Jackson also valued collecting household items used daily. Examples of such objects include buckets for water or mats to divide the home, work baskets for storing weaving materials or for collecting berries or grasses or shellfish, toys such as hide-covered balls and dolls, stone tools such as mauls and adzes, fishing equipment such as net shuttles and gauges, nets and hooks, hunting equipment including bows and arrows, snares, and traps, fire-starting implements such as drill bows, transportation-related items such as snowshoes and watercraft, etc., etc.

Jackson, according to Douglas Cole, was very concerned with keeping Alaskan cultural belongings in Alaska. He was keenly aware that collectors were buying items en masse and shipping them off to Washington, D.C., New York, Vancouver and elsewhere, and around the same time, tourists arriving by steamship in increasing numbers, were also purchasing and bringing home curios for their private collections.

In Captured Heritage, Douglas Cole wrote:

The motivations behind the new Sheldon Jackson Museum were mixed. Jackson, the moving spirit, seems to have become concerned about the drainage of native artifacts from the territory. … The museum, he wrote, in retrospect, had been founded after some of the distinguished visitors had brought home to him how the curios of the country were being bought up and carried away by tourists, so "that in a few years there would be nothing left to show the coming generations how their fathers lived." 17

Carlton wrote, “before the first half of the nineteenth century was complete, a serious drain of Alaskan material culture had begun to points around the globe,” and referenced collectors who competed with Jackson or had collected in Alaska just prior to his arrival, including but not limited to Edward Nelson, John Murdoch, Lt. George Thornton Emmons, Franz Boas, Fillip B. Jacobsen, John R. Swanton, and Edward Fast, among others. 18 The Smithsonian, British Columbian Provincial Museum, the American Museum of Natural History and other museums were all seeking to add Alaskan material to their collections around this time.

Did Jackson and his Presbyterian counterparts collect to convert? In her thesis, Carlton writes that Jackson’s efforts to assimilate Alaska Native peoples were focused on religion and education as opposed to collecting cultural belongings. “Jackson felt that if the Native people [of Alaska] became literate and could be educated to the white man’s lifestyle, the next logical step would be for them to accept the white man’s religion. 19 She went on, “Contrary to widespread belief, Jackson and his field workers were not collecting to deprive their potential converts of “heathen” objects which would delay their conversion…” and conceded:

“Certainly, there may have been individuals in some parts of the United States who practiced this, but realistically, most of the missionaries had no money to spare for such purchases nor the inclination to do so. Jackson, on the other hand, did have the funds available but was not so naïve as to think he could buy off or change Native customs by depleting their material culture in this manner. His personal interest in Native cultures and his confidence in education for affecting change would have stopped him short of this sort of “bribery. … The turning over of material culture as a symbol of adapting to a new way of life might have been a by-product of education, but the legends of missionaries taking away objects of Native cultures as a means of Christianizing them appears to be just that, legend – at least in Alaska.” 20

A Figure Who Still Divides Opinion

Perspectives on Sheldon Jackson and his legacy vary considerably, and he remains a controversial figure to this day. On the one hand, some academics and historians argue that he preserved much of Alaska’s material culture that would have otherwise been irretrievably lost or removed from Alaska; that he differed in his approach from other collectors, and that he was acting, at the time, with the best interests of Alaska Natives in mind. Others describe Jackson as egotistical, self-serving, racist, exploitative and not that different from Carlisle Indian School founder Richard Henry Pratt, the man whose philosophy was “Kill the Indian, and save the Man.” Some of Jackson’s critics such as Richard Dauenhauer have written, “the pursuit of acculturation by Jackson and his fellow Protestants through insistence on the elimination of native languages, and their replacement by English was individually and culturally destructive, ‘disastrous to native self-image and language survival.’” 21

Others do not defend or condone Jackson but caution contemporaries to consider the historical context in which Jackson was working and describe him as a man of his time and a 19th-century bureaucrat employed by the federal government and Presbyterian Church at a time when separation between church and state was largely lacking and Victorian-era values, mores, and assumptions about “science and progress” were widespread.

Jackson, they say, was in many ways a part of a reform tradition, though not the origin of it, and there were “contributions by Jackson which constitute significant departures from the reform tradition, departures made in the interest of greater awareness and acceptance of cultural diversity and integrity.” 22

Stephen Haycox underscored this notion when he wrote:

Jackson did not work for acculturation of Alaska’s native population in isolation. In many ways, he was an unexceptional representative of the late nineteenth-century Indian reform movement in the United States, which accepted acculturation as the best solution to the problems of continuing Indian warfare and the inexorable advancement of white settlement…Jackson implemented policies which were clearly less sensitive to native cultural diversity than those of Russian Orthodox missionaries. But in doing so, he did no more than the other thousands of federal and private reform activities who fanned out across the American West in the last half of the nineteenth century. 23

Jackson’s book, The Alaska Missions on the North Pacific Coast, is filled with his contradictory sentiments towards Alaska and its peoples. On one page, he praised and depicted indigenous “talent for carving in wood and bone” but several pages later, condemns other Native traditions. Jackson and his Presbyterian contemporaries sometimes applied the words “uncivilized” or “half-civilized” or “ignorant” in their descriptions of Alaska Natives, yet some claim that neither Jackson nor his counterparts were racist.

Sergei Kan wrote:

While negative about the Indian peoples’ traditional culture, nineteenth-century Presbyterians were not racist. They firmly believed that deep down all human beings were the same and that any rational and responsible individual could be regenerated through Christianity. They also believed that by accepting Christian-American civilization the Indian would eventually become equal to America’s White citizens and become a citizen himself; hence they differed from many of their American contemporaries. 24

While few historians would question that Indian boarding schools, with which Jackson is inextricably linked, inflicted trauma on indigenous communities, some scholars, such as Molly Lee caution:

A century after Jackson’s Alaska years, when the pervasive mores and values support ethnic plurality rather than assimilation, it is easy to cast aspersion on his career. To do so, however, is to judge him unfairly. Jackson’s dedication to the cause of converting Alaska Natives is but one isolated instance of a worldwide missionary crusade, one carried out with the absolute conviction that Western culture stood at the pinnacle of the evolutionary chain of being. Jackson’s aim to save the souls of every man, woman, and child in Alaska was informed by this assumption. At the same time, Jackson’s project was reinforced by the federal government’s ongoing neglect of its responsibilities for Alaska and its Native people. By appointing Jackson to the position of general agent of education for Alaska, the government granted him the authority to staff the Alaska schools with missionaries and design the educational curriculum to include a strong component of Christian doctrine. Whether or not we find the underlying assumption unpalatable, the separation between church and state was less clearly defined a century ago, and wholesale condemnation of that or racism inherent in the idea of the “Great Chain of Being” that formed it, amounts to a form of presentism.

Regardless of one’s opinion of Sheldon Jackson and his legacy, it is difficult to escape the irony of his work. Rosemary Carlton summarized it well when she wrote of his time and impact: “He came to Alaska to change Alaska Natives’ ways of life, encourage them to put aside their cultural values, yet he aggressively preserved some of the most important material culture for the benefit of future generations.” 25

Works Cited

- Carlton, Rosemary. Sheldon Jackson, the Collector, MA Thesis, Norman, OK, University of Oklahoma, 1992, pp. 66, 145, 140, 174, 72, 183, 224, 186, 3-16, 65, 71.

- Carlton, Rosemary. Sheldon Jackson: Plunderer or Preserver?. http://ankn.uaf.edu/Clan Conference2/2007/RosemaryCarlton.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2024.

- Cole, Douglas. Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts, Seattle, WA, University of Washington Press, 1985, p. 93.

- Haycox, Stephen. “Sheldon Jackson in Historical Perspective: Alaska Native Schools and Mission Contracts, 1885-1894.” Alaskool, http://www.alaskool.org/nativeed/articles/s haycox/sheldon_jackson.htm. Accessed 26 April 2024.

- Haycox, Stephen. “Putting the Sitka Industrial Training School in Context: Alaska Natives and the Federal Government. YouTube, uploaded by Friends of Sheldon Jackson Museum, March 2024

- Himmelheber, Hans. 1964 “Sheldon Jackson as Preserver of Alaska’s Native Culture,” in The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 33 (4), pp. 411-424.

- Jackson, Sheldon. Alaska and Missions on the North Pacific Coast. New York, NY, Dodd, Mead & Company, 1880

- Jacuk, Benjamin. “A Reindeer in Caribou’s Clothing: Sheldon Jackson’s Boarding Schools and Structural Violence. YouTube, uploaded by Museums Alaska, June 2023

https://youtu.be/mSW5h3ha6M4?si=Tvt0lG8Tz1SbsCVZ - Kan, Sergei. Memory Eternal: Tlingit Culture and Russian Orthodox Christianity through Two Centuries, Seattle, Washington, University of Washington, 1999, pp. 204-205

- Lee, Molly. “Zest or Zeal? Sheldon Jackson and the Commodification of Alaska Native Art,” in Collecting Native America, edited by Shepard Krech, Washington, D.C , Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999, pp. 62-82.

- Lee, Molly.1992 “Appropriating the Primitive: Turn of the Century Collection and Display of Native Alaskan Art” in Arctic Anthropology, Vol. 28, 1, pp. 6-15

- Oleska, Father Michael. “Civilizing” Native Alaska: Federal Support of Mission Schools, 1885-1906. January, 1991. Prepared for the National Education Association. Washington, D.C. by Father Michael Oleksa. https://missions.hchc.edu/articles/articles/civilizing-native-alaska . Accessed 14 May 2024.

- Postell, Alice. Where Did All the Reindeer Come From?, Portland, Oregon. Amaknak Press, 1990 Shlansky, Beatrice. “An Exercise of True Christian Stewardship”: Presbyterian Missionary Sheldon Jackson in Alaska (1877 – 1909), MA Thesis, NY, NY, Columbia University, 2022 https://history.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2022/05/Shlansky-Beatrice_Senior-Thesis-Update.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2024.

- Tower, Elizabeth. Reading, Religion, Reindeer: Sheldon Jackson’s Legacy to Alaska, Elizabeth A. Tower. Anchorage, AK. 1988, pp. 37-39, 39-43

- Williams, Maria Shaa Tlaa. 2009 “The Comity Agreement: Missionization of Alaska Native People” in The Alaska Native Reader: History, Culture, Politics, Duke University Press: Durham and London. p.153

- “Boarding Schools in Alaska featuring Benjamin Jacuk.” Coffee and Quak. From Episode 23, 8 June 2023, https://podcasts.apple.com/za/podcast/episode-23-boarding-schools-in-ak/id1414575353?i=1000616202145

Notes

- Carlton, 66

- Shlansky, Beatrice, 14

- Stewart 1907, 364

- Williams, Maria Shaa Tlaa, 2009, 153

- Carlton, 145

- Carlton, 140

- Tower, 37-39

- Tower, 37-39

- Tower, 39-43

- Carlton, 174

- Carlton, 183

- Carlton, 10

- Carlton, 203

- Carlton, 72

- Carlton, 224

- Carlton, 186

- Cole, 93

- Carlton, 3-16

- Carlton, 65

- Carlton, 71

- Haycox, 1

- Haycox, 2

- Haycox, 2

- Kan, 204-205

- Carlton, 5

Jacqueline Fernandez-Hamberg is curator of collections at the Sheldon Jackson Museum in Sitka, Alaska.