Watch video from “A New Step Every Day”

copyright Hudson West Productions

Season 1

A New Step Every Day (1920s–1930s)

Episode 3 explores the fast and furious 1920s and 1930s, when jazz was hot, credit was loose, and illegal booze flowed freely in underground speakeasies. Between performances, Feinstein illustrates the impact of talking pictures, the dawn of radio, and the fledgling recording industry. Additionally, it introduces viewers to other collectors and musicians who keep the spirit of the Jazz Age alive today.

Web Exclusive Video

Buy Them Today, Play Them Tonight

Copyright Hudson West Productions

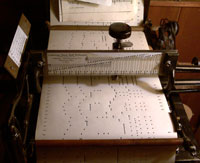

Before there were computers, synthesizers, MIDI controllers, sound cards, samplers and drum machines, there were piano rolls. But instead of decoding ones and zeros, piano rolls transmitted their musical information mechanically, with holes punched in a paper roll that moved across a tracker bar with 88 holes—one for each piano key. Each perforation would cause a note to sound by depressing a key when it crossed the corresponding hole in the tracker bar.

Composer Percy Grainger corrects a Duart piano roll recording.

source: Library of Congress

This seemingly simple but devilishly complex device came into being at the end of the 19th century and peaked in popularity around 1923. Peter Mintun, a musician, historian, and collector of music, artifacts and memorabilia of the 1920s and ’30s, has amassed not only hundreds of piano rolls, but the reproducing pianos needed to play them. (Much like the old VHS versus BetaMax wars of the 1970s, different brands of player pianos and piano rolls were incompatible with one another.) In this video, Peter demonstrates to Michael Feinstein a prized roll from 1925, on his immaculately maintained Welte-Mignon grand.

A Leabarjan Music Roll Perforator.

source: Peter Mintun

The most sophisticated player pianos not only reproduced notes exactly; so-called “expression rolls” could also mechanically depress the sustain pedal, and adjust dynamics from piano to forte, exactly as programmed on the roll. Famous composers and pianists such as George Gershwin, Ferde Grofe, Richard Rodgers, and Vincent Youmans recorded piano rolls of their own songs. Other “name brand” musicians such as Harry Perella and Roy Bargy (pianists in the Paul Whiteman orchestra) made rolls and were prominently featured on the labels.

The heyday of the player piano was brief. Between 1910 and the mid-1920s piano rolls were actually more popular than recordings, because the technology of the time (on cylinders or platters) was primitive and the piano was especially difficult to record well. But by 1924 radios were coming into homes and electrical recording had been invented, with vastly improved fidelity. The 1929 stock market crash was the death knell of the industry. But thanks to historians and collectors, we can still enjoy the unique, exuberant sound of the invisible piano player with magic fingers.

Providing support for pbs.org. Learn more