Great Minds Think Alike:

How Alfred Wallace Came to Share

Darwin's Revolutionary Insight

by Sean B. Carroll

Parallel tracks

The search for the origins of species, both in general and of

specific kinds of creatures, has entailed a series of truly

epic adventures over the past 200 years. Throughout 2009, the

200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin, the world is

marking the achievements of our greatest naturalist and the

leader of a far-reaching scientific revolution.

Darwin's great voyage and works are well known, and rightly

so. But the making of the theory of evolution and its early

growth and acceptance also owe a considerable debt to Alfred

Russel Wallace, who undertook two long voyages under yet more

difficult conditions, and independently reached very similar

conclusions to Darwin.

Wallace's dramatic story and scientific contributions are

generally much less well known. The writer C.W. Ceram

described adventure as "a mixture of spirit and deed," and I

think no naturalist's experiences better fit that definition

than Alfred Wallace's. I will highlight some of his adventures

and discoveries, show how he developed similar ideas as

Darwin, and offer a glimpse into the very warm relationship

that emerged between the two great naturalists.

The two men had a number of traits in common. Both were eager

to escape England and to explore the glories of the Tropics.

Both did so as young men—Darwin was 22 when he boarded

the HMS Beagle, and Wallace was 25 when he first left

England. Above all, they were each prodigious collectors, and

through collecting they developed an appreciation for the

variety each species exhibited. From this very hard-earned

knowledge, they evolved from collectors into scientists, who

asked not just what creatures existed in a given place but how

they came to be, and these questions led each man to unique

and shared discoveries.

Deep into Amazonia

In 1847, Wallace proposed to his friend and fellow collector

Henry Walter Bates that they travel to the Amazon. His

principal motivation was to build a personal natural history

collection. But Wallace was also well-read on scientific

topics of the day. Unlike Darwin, who did not set out with any

intent of gathering evidence for or against any great idea,

Wallace suggested to Bates that on their journey they could

"gather facts toward solving the problem of the origin of

species." That problem, circa 1847, pivoted on a potent

question: Were species immutable and specially created by God,

or changeable and the product of natural processes?

Wallace and Bates were self-taught amateurs who did not have

the family financial resources that Darwin had, or the

connections with academia, or berths on a British naval

vessel. They had to make their way to the Amazon on a

commercial trading ship and then cover their expenses by

shipping prized specimens back to England for sale.

They arrived in Para on the northeast coast of Brazil in May

1848. After a time exploring the region they split up, with

Wallace heading up the main trunk of the Amazon and then up

the Rio Negro and its largest branch, the Rio dos Uaupés.

By 1852, after four years of arduous travel and collecting, he

was 2,000 miles upriver from the Atlantic Ocean, farther than

any European had ever gone.

But he was spent. Physical exertion, poor nutrition, and

tropical diseases had weakened him to a state in which he

feared that if he did not turn back he would die in the

jungle. In addition to many preserved specimens that he had

with him and stored downriver, Wallace had accumulated a large

menagerie of live animals—monkeys, macaws, parrots, and

a toucan—that he hoped to take all the way to the London

Zoo. Their upkeep was draining him of what little energy he

had remaining.

Wallace headed back downriver to Para. He found a ship headed

for England, the brig Helen, boarded it with 34 live

animals and many boxes of specimens and notes, and set sail

for home.

Lost at sea

Four weeks into the journey and about 700 miles east of

Bermuda, the Captain came to Wallace's cabin and said, "I'm

afraid the ship's on fire; come and see what you think of it."

Wallace followed the Captain to the hold and saw smoke pouring

out of it.

The crew could not douse the smoldering blaze. The Captain

ordered down the lifeboats. Wallace went to his hot, smoky

cabin and salvaged a small tin box and threw in some drawings,

some notes, and a diary. He grabbed a line to lower himself

into a lifeboat, slipped, and seared his hands on the rope.

His pain was compounded when his injured hands hit the

saltwater. Once in the lifeboat, he discovered it was leaking.

Wallace watched his animals perish and the Helen burn,

along with all of his specimens.

"And now everything was gone, and I had not one specimen to

illustrate the unknown lands I had trod..."

And so there he was, lying on his back in a leaky lifeboat in

the middle of the Atlantic. Day after day passed in the open

boats. Wallace was blistered by sunburn, parched with thirst,

soaked by sea spray, exhausted from constantly bailing water,

and near starvation. At last, on the tenth day, they were

picked up.

Aboard his rescue ship, Wallace began a letter to a friend in

Brazil detailing his ordeal and the magnitude of his loss:

"How many weary days and weeks had I passed, upheld only by

the fond hope of bringing home many new and beautiful forms

from those wild regions; every one of which would be endeared

to me by the recollections they would call up... And now

everything was gone, and I had not one specimen to illustrate

the unknown lands I had trod...."

Wallace wrote to his friend that "fifty times" on the voyage

home he had sworn to himself "if I once reached England, never

to trust myself more on the ocean." If he had held to that

promise, his story would end here and few would have ever

heard of Alfred Wallace again. But, as he wrote to his friend,

"good resolutions soon fade...." Wallace decided that, despite

his loss and near death, he would voyage again.

To the Malay Archipelago

Wallace's lust for exploration and collecting was not

satisfied, nor was his interest in the origin of species. That

mystery was still unsolved as far as the scientific world knew

in 1852. Though Darwin had reached his conclusions many years

earlier, his ideas were known to only a few intimates, and

Wallace was not one of them.

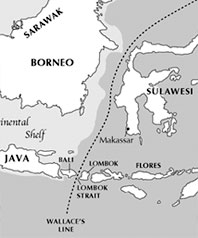

Wallace began to ponder his next destination. He had to

collect quarry that would fetch good prices, but he ruled out

a return to the Amazon. He began thinking about the Malay

Archipelago, the vast group of islands between Southeast Asia

and Australia (see map). Other than those on the island of

Java, the animals and plants of the region were unknown.

Enough fragments of natural history were emerging from the

Dutch settlements there to convince Wallace that it offered

both rich pickings and good facilities for a traveler.

The islands span more than 4,000 miles from east to west and

1,300 miles from north to south, an area almost as large as

the entire continent of South America. Covered in tropical

forest, the islands might appear similar, but some held

different treasures, and discovering and explaining the

differences would put Wallace, literally, on the map.

Wallace arrived in Singapore in April 1854 and set out to

explore the country. He would encounter altogether different

treasures, and dangers, than those on the Amazon. For example,

there were tigers roaming about Singapore; they killed on

average one resident a day. Wallace occasionally heard their

roars, and in typical British understatement he noted that "it

was rather nervous work hunting for insects ... when one of

these savage animals might be lurking close by..."

Germinating ideas

Unflustered by such concerns, Wallace followed a daily

routine. Up at 5:30 a.m., he started the day with a cold bath

and hot coffee. He sorted out the previous day's collection

and then set out again into the forest with his gear. He

carried a net, a large collecting box hung on a strap over his

shoulder, pliers for handling bees and wasps, and two sizes of

specimen bottles for large and small insects, attached by

strings around his neck and plugged with corks. On some days,

he carried a rifle.

"I naturally expected to meet with some of these birds again;

but during a stay there of three months I never saw one of

them..."

Despite some reputation for ferocity, the native tribesmen in

parts of the archipelago he visited shared their knowledge of

the forest with Wallace and helped him to find what he was

after. He stalked the islands' most beautiful and prized

natural riches—orangutans, monkeys, spectacular birds of

paradise, and enormous, brilliantly colored butterflies.

Wallace mused that:

"Nature seems to have taken every precaution that these, her

choicest treasures, may not lose value by being too easily

obtained. First, we find an open harbourless, inhospitable

coast, exposed to the full swell of the Pacific Ocean; next, a

rugged and mountainous country, covered with dense forests,

offering [in] its swamps and precipices and serrated ridges an

almost impossible barrier to the central regions; and lastly,

a race of the most savage and ruthless character...."

Wallace was paying close attention to the diversity of species

he found, the variety among the individuals of each species,

and where he found them. These were the practical

concerns of a paid collector but also the catalysts of his

transformation into a scientist.

For example, while pursuing beautiful birdwing butterflies,

which were coveted for their large wingspan and rich

coloration, Wallace noticed that different birdwing types were

restricted to particular islands. These butterflies signaled

to him just what the birds of the Galapagos archipelago

signaled to Darwin—that species change.

While Darwin was keeping quiet about evolution, Wallace was

thinking out loud, putting his thoughts on paper and firing

them off to magazines and journals in England. Some of these

were short field notes; others revealed bigger ideas. But

Wallace had none of the concerns that restrained Darwin. He

had a reputation to make, and nothing to lose.

A law of nature

In 1855, while waiting out the wet season in Sarawak, on

Borneo, Wallace wove together threads of geology and natural

history to propose a new law:

Every species has come into existence coincident both in

space and time with a pre-existing closely allied

species.

Wallace thought that species were connected like "a branching

tree." He was proposing that new species come from old species

as new twigs grow from older branches. This bold idea refuted

the then-dominant doctrine of special creation—that each

species was specially created, in one moment, to fit the land

it inhabited. Moreover, Wallace used some of the very

arguments that Darwin had agonized over for almost two decades

but had not yet published.

Wallace supported his "Sarawak Law" with all sorts of

observations on the distribution of species, especially those

on islands. For example, the Galapagos, he wrote, "which

contain little groups of plants and animals peculiar to

themselves, but most nearly allied to those of South America,

have not hitherto received any, even a conjectural

explanation." Wallace was referring to Darwin's observations,

which had not been explained.

Wallace pointed out that families of butterflies, birds, and

various plants are confined to certain regions. He had noticed

when he was in the Amazon that some species of monkeys were

confined to one side of the river. "They could not be as they

are," he wrote, "had no law regulated their creation and

dispersion." By "dispersion," Wallace meant that the extent to

which a species could spread out over the land was constrained

by features of the land—rivers, mountain ranges, and so

forth.

Almost no one read or noticed the paper when it first

appeared. Wallace heard nothing from England about his Law,

except for some grumblings that he should focus on collecting

and not theorizing.

Drawing a line

Wallace went island-hopping quite often. He made 96 journeys

totaling about 14,000 miles and visited some of the same

islands several times over the span of eight years. Often the

availability, or unavailability, of a boat determined his

path. One day in May 1856, he took a Chinese schooner from

Singapore to Bali, which he had no intention of visiting, but

he figured he could find a way from there to Lombok and then

on to Makassar on the island of Sulawesi. This accidental

detour would give Wallace the most important discovery of his

expedition.

On Bali, Wallace found kinds of birds as on the other islands

he had visited to the west, including a weaver, a woodpecker,

a thrush, a starling—nothing too exciting. But then,

"crossing over to Lombok, separated from Bali by a strait less

than twenty miles wide, I naturally expected to meet with some

of these birds again; but during a stay there of three months

I never saw one of them...." Instead, Wallace found a

completely different assortment: white cockatoos, three

species of honey-suckers, a loud bird the locals called a

"Quaich-Quaich," and a really strange bird called a megapode

("big foot") that used its big feet to make very large mounds

for its eggs. None of these groups were known on the western

islands of Java, Sumatra, or Borneo.

Now here was a puzzle. What constraint prevented the spread of

these species from island to island? Surely, birds could cover

a 20-mile strait with little trouble.

"The life of wild animals is a struggle for existence."

Wallace described the mystery in a letter to Bates. He

theorized that there was some kind of invisible "boundary

line" between Bali and Lombok. Traveling farther east to

Flores and Timor, the Aru Islands, and New Guinea, the

changeover in bird life was very clear. All the families of

birds that were common on Sumatra, Java, and Borneo were

absent from Aru, New Guinea, or Australia, and vice versa. The

differences in mammals among the western and eastern islands

were just as striking. On the large western islands there were

monkeys, tigers, and rhinoceri. But on Aru there were no

primates or carnivores. All the native mammals were

marsupials—kangaroos, cuscus, and the like.

That line between Bali and Lombok was real, and it signified

something very profound to Wallace. He put his thoughts to

paper again. Wallace pointed out that under the doctrine of

special creation, one would expect to find similar animals in

countries with similar climates, and dissimilar animals in

countries with dissimilar climates. This is not at all what he

saw.

Comparing Borneo (in the west) and New Guinea (in the east),

he wrote, "[I]t would be difficult to point out two [lands]

more exactly resembling each other in climate and physical

features." But their birds and mammals were entirely

different. Comparing New Guinea and Australia, he wrote, "we

can scarcely find a stronger contrast than in their physical

conditions ... the one enjoying perpetual moisture, the other

with alternations of excessive drought." Wallace reasoned, "If

kangaroos are especially adapted to the dry plains and open

woods of Australia, there must be some other reason for their

introduction into the dense damp forests of New Guinea...." In

the tropical forests of the eastern islands, tree kangaroos

occupied the habitat occupied by monkeys in the west.

Wallace reasoned further that "some other law has regulated

the distribution of existing species." That law, Wallace

suggested, was the "Sarawak Law" he had proposed two years

earlier. Again Wallace relied on geology to make his case. He

surmised that New Guinea, Australia, and Aru must have been

connected at some time in the past and so share similar sets

of birds and mammals. Similarly, Wallace deduced that the

western islands had once been part of Asia and so share the

fauna of tropical Asia—monkeys, tigers, etc.

Wallace was right. He had linked the question of the origin of

species to how species were distributed, and he had defined a

dividing line between the fauna of Asia and Australia. His

discovery would forever after be known as the "Wallace Line"

and Wallace himself as the founder of biogeography, the

science dealing with the geographical distribution of plants

and animals.

Meeting of the minds

For Wallace the question, then, was not if species evolved but

how? Baking in a malarial fever on the volcanic island of

Ternate in early 1858, the answers came to him.

Alternating between hot and cold fits, Wallace had nothing to

do but "think over subjects then particularly interesting to

me." Wrapped in a blanket on a 88°F day, he thought of the

English economist Thomas Malthus's essay on population, which

he had read some years earlier. It occurred to him that the

diseases, accidents, and famine that Malthus argued check the

growth of human populations act on animals, too. He thought

about how animals breed much more rapidly than humans and, if

left unchecked, would overcrowd the world very quickly. But

all of his experience revealed that animal populations were

limited. "The life of wild animals is," Wallace concluded,

"a struggle for existence" [my italics—watch

for more below, and for why I highlight them]. Wallace

continued: "The full exertion of all their faculties and all

their energies is required to preserve their own existence and

provide for that of their infant offspring." Finding food and

escaping danger ruled animal lives, and the weakest would be

weeded out.

Wallace the great collector was intimately familiar with the

variety of individuals of a species. "Perhaps all the

variations ... must have some definite effect,

however slight, in the habits of or capacities of the

individuals ... a variety having slightly increased powers ...

must inevitably acquire a superiority in numbers."

"I know not how or to whom to express fully my admiration of

Darwin's book."

Wallace wrote the paper out in its entirety in just a few

nights. He entitled it "On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart

Indefinitely From the Original Type." Wallace's paper was just

a sketch, conceived in a dilapidated house on an

earthquake-ravaged island during bouts of fever, 10,000 miles

from the center of science in England. Wallace did not send it

directly to a journal; he wanted others to look at it first.

So he sent it to a naturalist with whom he had begun a

correspondence—Charles Darwin.

Darwin received Wallace's paper sometime in June 1858. He was

shocked when he read it. The reason for that shock is

especially clear when one considers what Darwin had recently

written in drafts of two chapters for a large book he was

working on and compares it with the language of Wallace's

paper.

In February 1857, Darwin had composed Chapter 5 of his book

and entitled it "The Struggle for Existence as

Bearing on Natural Selection" [again, my italics]. The next

month he had completed Chapter 6, in which he explained that:

"All Nature ... is at war. ... The struggle very often falls

on the egg & seed, or on the seedling... any

variation, however infinitely slight, if it

did promote during any part of life even in the slightest

degree, the welfare of the being, such variation would tend to

be preserved or selected."

Neither author was aware of the other's thoughts and writing.

How can we explain the remarkable similarities in

language—"the struggle for existence" and "slight

variation"?

Great minds think alike.

Both men had seen nature up close and understood it was a

battlefield. Both men had collected enough specimens of

individual species to appreciate that species were variable.

Both men had seen slightly different species restricted to

particular islands and concluded that species change. Both men

had read and recognized the relevance of Malthus's essay on

populations. Confronted with similar evidence, they had

reached very similar conclusions.

Nonetheless, Darwin, more than 20 years after his first

insights into species formation, feared that "all of my

originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed."

"A little proud"

What happened thereafter is still a subject of debate among

scholars. The facts are that Wallace had asked Darwin to

forward the manuscript to the geologist Sir Charles Lyell,

which Darwin did. Lyell and J.D. Hooker, the eminent botanist,

were intimates of Darwin, to whom he had divulged his theory

of natural selection and much of the argument supporting it.

Lyell and Hooker took the initiative to arrange for Wallace's

paper, and a brief sketch from Darwin on his theory, to be

read together at an upcoming meeting of the Linnaean Society

and to be published together.

Was Wallace robbed of his individual right to glory? Was the

arrangement of joint publication fair? (Wallace was not

informed of it until after the fact.) It was Darwin who had

coined the term "natural selection," and he had shared his

1842 sketch, at least privately, with other scientists.

It is true that Darwin's name and works are far better known

than Wallace's today. But consider Wallace's perspective on

the matter. While still in the Malay Archipelago, he received

a copy of the Origin of Species from Darwin. He

read it over and over. Then he disclosed his reactions in a

private letter to his longtime friend Bates:

"I know not how or to whom to express fully my admiration of

Darwin's book. ...I do honestly believe that with however much

patience I had worked up & experimented on the subject I

could never have approached the completeness of the

book,—its overwhelming argument, & its admirable

tone & spirit. ... Mr. Darwin has created a new science

& a new Philosophy, & I believe that never has such a

complete illustration of a branch of human knowledge, been due

to the labours and researches of a single man."

Not in this letter nor for the rest of his long life—he

lived to 90—did Wallace utter a word of regret, envy, or

resentment.

Perhaps for Wallace it was simply a matter of being accepted.

He was, up until 1858, an outsider to the circle of eminent

scientists who led the new revolution in thought. When he

heard that Lyell and Hooker had made complimentary remarks

about his paper, he wrote his oldest friend and school-fellow

that "I am a little proud...." Wallace did not need

or seek to be the center of the circle; he just wanted to be

let inside. That, and more, he surely earned.