Following the Chemicals: Documenting PFAS Contamination in Southern Communities

Reporters and filmmakers talk about making the documentary ‘Contaminated: The Carpet Industry’s Toxic Legacy,’ an on-the-ground look at how industry, regulators and communities have navigated contamination by forever chemicals.

February 20, 2026

Share

Among us are tasteless, colorless, odorless chemicals, known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS for short. Used widely in household products for their stain-, water- and heat-resistant properties, PFAS are known as forever chemicals because they can take decades or more to break down.

They’re also found in our bodies, homes and drinking water. Research has linked exposure to the chemicals to an increased risk of serious health issues.

How did PFAS, once used in popular stain-resistant carpets, contaminate the water and environment in parts of Georgia and Alabama? That’s what a multiplatform collaboration supported by FRONTLINE’s Local Journalism Initiative set out to investigate. With The Associated Press, journalists in local newsrooms at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Post and Courier and AL.com reviewed thousands of pages of court records and interviewed scientists, former regulators and industry insiders along with residents in Georgia and Alabama with illnesses linked to PFAS contamination.

The investigation culminated in a series of articles and the documentary Contaminated: The Carpet Industry’s Toxic Legacy. Carpet companies said they are not to blame for PFAS contaminating the environment, saying the companies that made PFAS assured them that the chemicals were safe. The journalists found records that showed executives at two leading carpet companies received warnings going back decades about the potential harm posed by some kinds of PFAS.

The reporting found that, as scientific research showed that early PFAS compounds might be dangerous, carpet manufacturers and their chemical suppliers switched to new stain- and soil-resistant products — made with different types of PFAS. The industry says that it always complied with legal and regulatory standards, which have been slow to address the issue. Contaminated explores how communities and local governments across the South are grappling with how PFAS contamination has affected their environment and health.

Filmmaker Jonathan Schienberg describes the project as “holding up a mirror.” He said, “We’re trying to reflect how the system works and letting people decide if they think that’s good or not.”

In a conversation with FRONTLINE, the project’s reporters and filmmakers discussed what it was like to bring this investigation to life.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The Reporters

FRONTLINE spoke to Dylan Jackson of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Jason Dearen of The Associated Press and Margaret Kates of AL.com.

Can you share how this investigation first began?

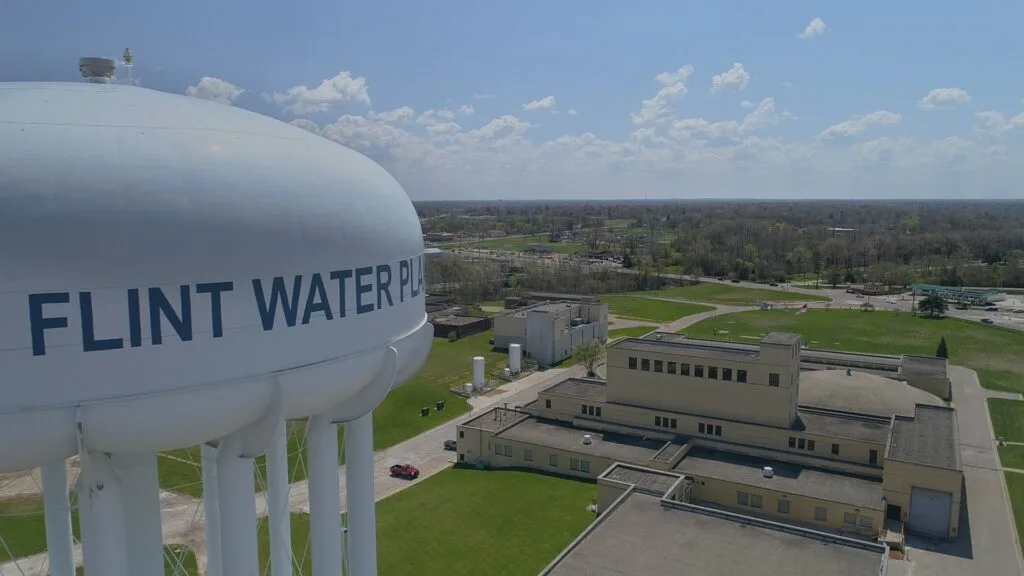

Jackson: When my reporting partner, Justin Price and I were reviewing newly released federal environmental data we came across a round of testing related to PFAS, or forever chemicals, in public water systems. At the time, we didn’t know much about PFAS, but the data showed a clear hot spot in northwest Georgia, which gave us a starting point. What took the story to the next level was realizing this wasn’t just about contamination in northwest Georgia.

There was a compelling narrative involving power structures in the region — the carpet industry, the chemical industry, and how they intersected with the contamination crisis. Once we obtained a trove of court documents, including internal emails and depositions from key industry leaders, we were able to move past just identifying the problem and started examining accountability and the systems behind it.

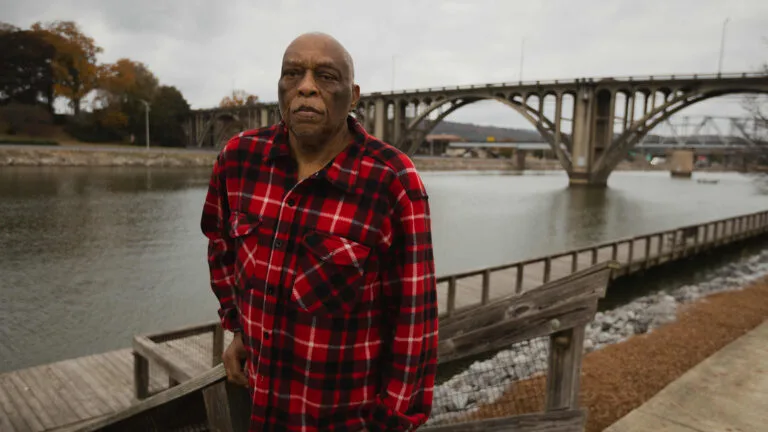

Kates: That’s when I was brought in. My editor called and said we had been asked to join a project. She explained that Dylan and his editor Brad Schrade had identified Gadsden, Alabama, as one of the communities affected by PFAS contamination in the Coosa River. I already had written a couple of daily stories about related lawsuits, so I began reporting on the Alabama side of the story.

Dearen: AP has a local investigative reporting program that partners with newsrooms. I’ve covered environmental issues for a long time, so my AP colleagues Ron Nixon and Justin Pritchard approached me to gauge my interest. From there, I spoke with Dylan and Brad to get a sense of what they were looking to do, and once we started reporting together, it became clear pretty quickly that this was a massive story, which made it a good one to collaborate on.

What stood out to you during your preliminary research and reporting?

Dearen: I learned from talking with these reporters and people in the region that they suffer from a lack of information about PFAS and its contamination risks. There was a lot of confusion about what was happening, what it meant, and who should be held accountable. We saw an opportunity to provide people with a reliable resource about something affecting their health and their families.

Kates: In the early days, I was struck by how contamination crossed state lines through the river system. The landscape of Alabama is really one of rivers. They connect the northern part of the state to the south. What stayed with me was that communities like Gadsden didn’t choose to bring in an industry that later contaminated their water. This was from out of the state.

Jackson: I’m really a political and business reporter at heart, so those aspects of the story really jumped out at me. There had been a lot of great reporting done by our environmental team surrounding the chemicals. But the company/local government aspect of the story gave it a new conversation that the lawsuits brought to life.

This investigation involves people’s health and medical histories. How did you build trust with the people who were affected and get them to share such sensitive information?

Jackson: For me, it’s just being there. I’ve probably made 40 trips to northwest Georgia over the course of this investigation, just checking in on people.

Forever Chemicals, Carpet Companies and a ‘Crisis That’s Not Fully Understood’

Transparency mattered — being clear about what we were doing, staying in touch, and not just showing up to take what we needed and leaving.

Records and data are essential in investigative reporting, but what truly makes the story impactful are the people in the region. They’re the ones who are being affected by the decisions being made around them and above them. So it’s important to just show people that you’re as committed to the work as they are to their lives there. Because even after this story publishes, their families are still there, and they remain.

What challenges did each of your newsrooms face when taking on an investigation of this scale?

Dearen: PFAS science is still evolving, so there was a learning curve. Our job was to understand what the scientists know, what they don’t know, and how to communicate risk accurately without overstating it.

PFAS are ubiquitous — it’s already in our bodies and all over the world. It’s such a huge subject that it’s going to be a long-term story. I think all of us came away with a much deeper understanding that we’ll carry forward in future reporting.

What do you most hope audiences take away from this story?

Kates: I report in places that are often marginalized or undercovered, like Gadsden. I want people to be informed about how PFAS entered the city’s drinking water, without creating a sense of hopelessness. There are solutions to removing PFAS from the water. They are expensive, but there’s a solution and accountability.

Jackson: At the AJC, our goal is to provide information to people in Georgia. This is a story that requires resources and time many newsrooms don’t have. I hope readers come away with a clearer understanding of PFAS, something that’s going to affect their lives for generations. I want those in northwest Georgia, specifically, to get a better understanding of who is accountable and how to navigate this crisis.

Dearen: So much national media is centered in New York and Washington, D.C. To have reporters investigating a story like this in the U.S. South, an area that’s often uncovered by national outlets, really matters. I hope this project encourages more collaborations like this, so that we can help bolster and amplify the work that these folks are doing because it helps strengthen local investigative reporting.

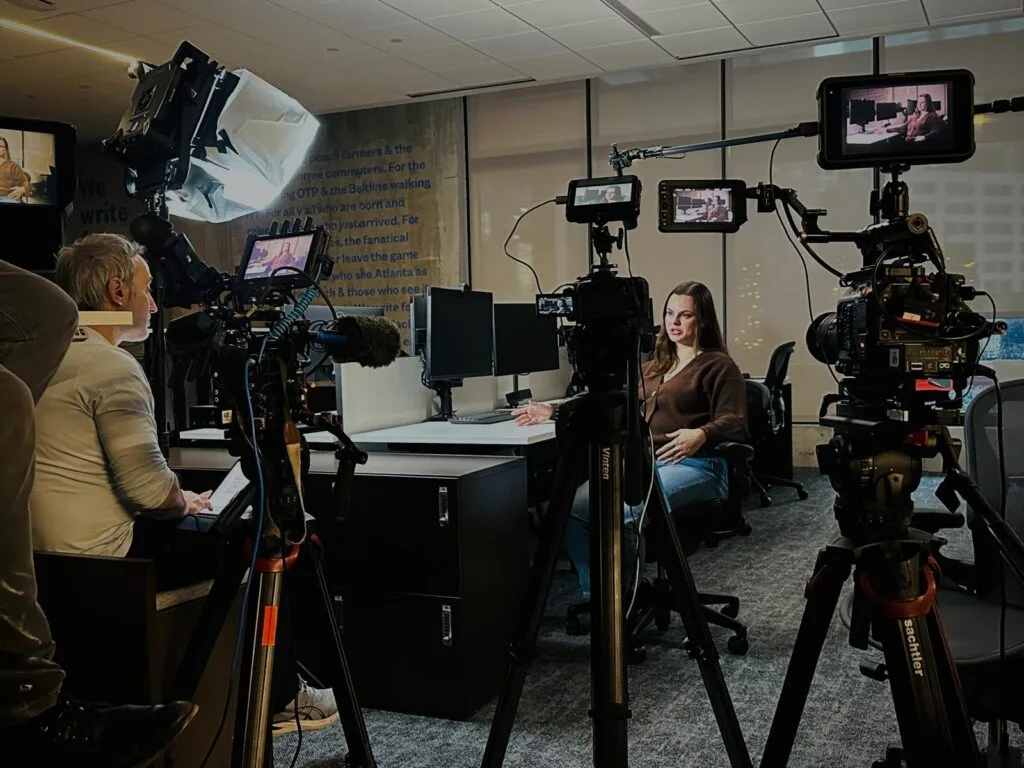

When you joined the project, I’m curious what it was like working with the producers on this story and being on camera?

Jackson: It was my first time participating in a project like this. There’s definitely a learning curve. On-camera reporting and print reporting are different. I could just drive up on a Saturday, with a notebook and recorder, pop into people’s houses, call them up, meet them for lunch. There’s a more solitary, informal aspect to print reporting that can’t be replicated as much for film, which requires more resources and a different approach.

I can’t say enough about how incredible the producers and folks at FRONTLINE were. Their reporting skills and mastery of their craft is incredible. They were side by side with us the whole time and had a lot to catch up with and did that well. It was really an incredible experience, and I appreciated working with FRONTLINE and everybody who put this film together.

The Filmmakers

FRONTLINE spoke to director and producer Jonathan Schienberg and producers Kate McCormick and Dana Miller Ervin.

When you joined the project, what did the collaboration with the reporters look like?

Schienberg: When we joined, the reporters had already been digging in for months. They were hitting the ground to start their reporting and we didn’t want to miss that, so we had to get up to speed quickly, which meant reading thousands of pages of documents, planning shoots and vetting sources all at once. It was intense, but our partners were incredibly generous and helped bring us up to speed.

PFAS are odorless, tasteless and colorless. How did you think about creating visuals for a story about such chemicals?

McCormick: Jonathan and Tim Grucza, our director of photography, were very conscious about this from the beginning. We ended up with a lot of really stunning imagery of the river systems and that became our primary metaphor and way of visualizing what was happening.

I remember talking to Tim about one of our shoot days, and he said, “Let’s do this first thing in the morning. That’s when you’re going to get this beautiful footage.” And he was right. The rivers became central to how we showed the story visually.

Schienberg: When we shot in Alabama, we got footage of mist coming off the Coosa River, and it was epic. We were very careful not to misrepresent that or make people think the mist itself was PFAS. But seeing the river and its systems was really captivating. That imagery, paired with the access we had to Dalton Utilities, was important. The drone footage made the infrastructure look almost otherworldly.

Especially when we were explaining the land application system, you really need a visual. When you start talking about wastewater treatment, people’s eyes glaze over and unless you have a way to visualize that it can be hard to follow.

What strategies did you use to make complex scientific information accessible to the public?

McCormick: It was a challenge throughout. There are an estimated 15,000 PFAS varieties — which means you’re dealing with tons of obscure acronyms. Early on, we decided to avoid the alphabet soup and focus on clear language. Experts were incredibly generous in helping us understand the science well enough to explain it accurately.

Schienberg: FRONTLINE is good at getting into the weeds without losing people. This story requires some chemistry education, but we had to be careful not to overwhelm viewers. The balance was critical.

How did you approach the accountability interviews, and did you run into any hurdles on showing that aspect of the investigation on camera?

Miller Ervin: Accountability was a challenge. I tried relentlessly with various key players, but there is ongoing litigation. While some spoke on background, few agreed to appear on camera.

Schienberg: We eventually got statements from industry and regulators, but I think it would have been useful to be able to sit down with them on camera. That’s better for journalism and for the audience.

Miller Ervin: It’s also better for the companies. They do a much better job of presenting their arguments in person.

McCormick: That’s why speaking with Georgia state Rep. Kasey Carpenter was so valuable. Hearing his perspective on PFAS, industry and legislation added important context to the film.

How did you balance telling the stories of individual towns and maintaining a broader national perspective?

Miller Ervin: In the first few weeks, we were doing Zoom calls with everyone we could, trying to learn how to approach this story. And I remember one of the first phone calls we had with Jesse Demonbreun-Chapman from the Coosa River Basin Initiative, he said that we had to grasp that this was a failure of accountability at every level. That became our guiding light.

McCormick: We knew early on we needed a national lens. We spoke with prominent attorneys, scientists and advocacy groups from the beginning. That groundwork mattered. However, this was a project that started with local journalism so local people were always at the center of the story. Dalton was the heart, with Calhoun and Gadsden showing how far the impact spread.

We couldn’t have told this story without people on the ground who were willing to take the risk, to trust us, and to share their experiences on camera. So I just give them all the credit in the world.

Watch the documentary

Contaminated: The Carpet Industry’s Toxic Legacy

How did PFAS chemicals once used in popular stain-resistant carpets end up in the water and environment in parts of Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina?

Keep Our Journalism Strong. Donate Today.

Your support makes it possible for FRONTLINE to produce bold investigative documentaries on the issues that matter most. Donate today to help sustain this work through the months and years ahead.

Email:

jala_everett@wgbh.orgRelated Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Related Stories

Related Stories

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.