A Window Into the Moscow Life of Wirecard’s Jan Marsalek

Once an executive at a European financial services firm, Jan Marsalek is now a fugitive with an international arrest warrant. A team of reporters managed to find Marsalek in Moscow.

By

Jörg DiehlRoman DobrokhotovChristoph GiesenChristo GrozevRoman HöfnerRoman LehbergerFidelius SchmidThomas SchulzAnika ZellerOctober 16, 2025

Share

One of the most-wanted men in Europe seems relaxed as he strolls across Moscow’s Trubnaya Square on July 1, 2025. A pair of sunglasses is dangling from the collar of his white T-shirt and his girlfriend’s hand is clutched in his own. By all appearances, a nice couple. Tatiana and Jan.

They both share the experience of having started a new life. He was once the chief operating officer of Wirecard, the infamous financial services company traded on Germany’s blue-chip stock index Dax. She was a Turkish language translator at an airport in Moscow. Now, it seems they also share an employer: the Russian domestic intelligence service known as the FSB. Agents working on behalf of Moscow.

Their story has all the elements of a spy thriller. Netflix material. Romance. An assassination plot. Attempted kidnappings.

At the center of the story is Jan Marsalek: a fugitive wanted on an international arrest warrant and accused of systematically defrauding investors and lying to clients while at Wirecard — one of the rising stars on the German stock index until it imploded in a massive scandal in 2020. Billions of euros vanished and 6,000 employees lost their jobs in one of the biggest cases of fraud in post-war German history.

Since embarking on a life on the lam, Marsalek has used disguises, numerous identities and a collection of real and fake passports. He has remained untouchable for the European investigators, prosecutors and intelligence agencies that have been on his trail for the past five years.

But a team of reporters from DER SPIEGEL, the German public broadcaster ZDF, the Austrian daily Der Standard, the Russian investigative platform “The Insider” and FRONTLINE (PBS) managed to find Marsalek in Moscow and spent over a year observing him, reviewing travel records, cell phone and chat data, photographs, court and law enforcement documents, and interviewing investigators, experts and government officials.

This reporting is part of an ongoing project that includes an upcoming documentary, and provides the most detailed insight yet into Marsalek, his alleged crimes, his relationship with Russia and his role with its intelligence services.

Read DER SPIEGEL’s version of the investigation.

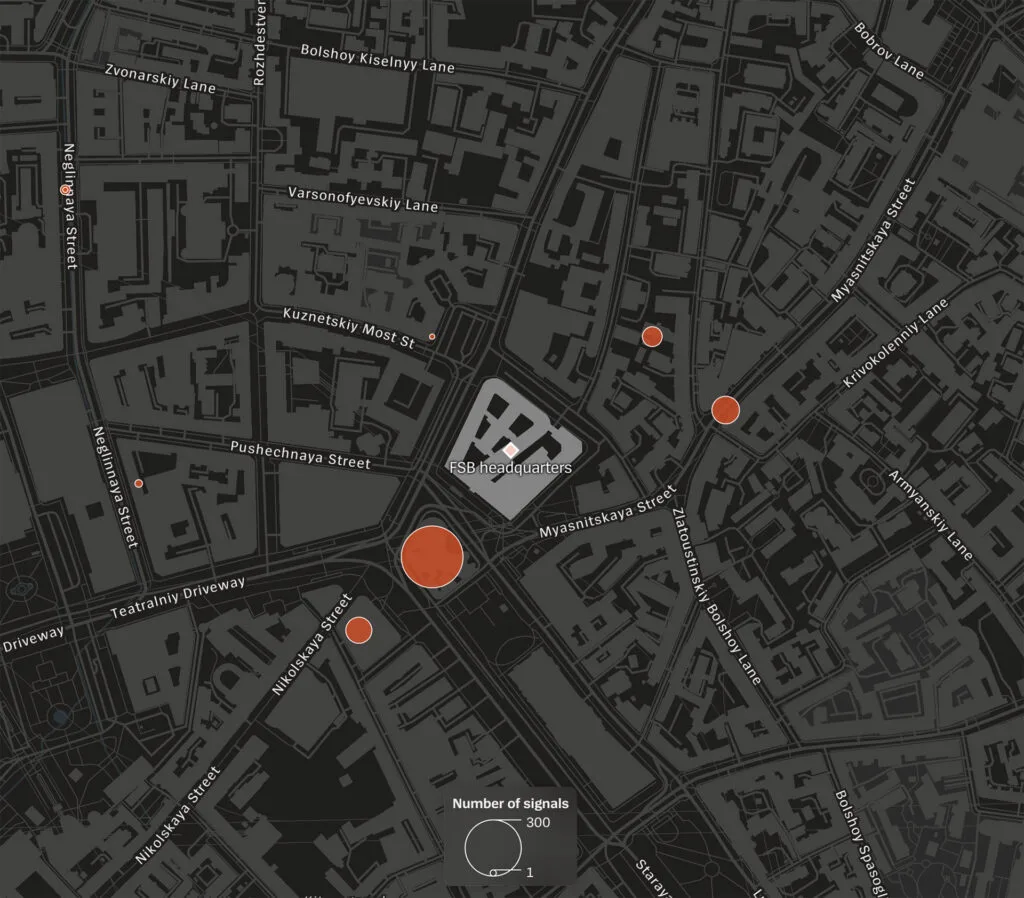

Marsalek often passes through the turnstiles of the Moscow subway station Lubyanka in the morning, just a few steps from the fortress-like headquarters of the FSB (Federal Security Service). He frequently appears in images from surveillance cameras at the site, such as in March 2025, when he was wearing a dark blue suit, dark blue tie and black glasses, with his hair cut short.

Other images the team of reporters reviewed show him making his way through the summery shopping streets of Moscow, winding his way along the sidewalks on an e-scooter.

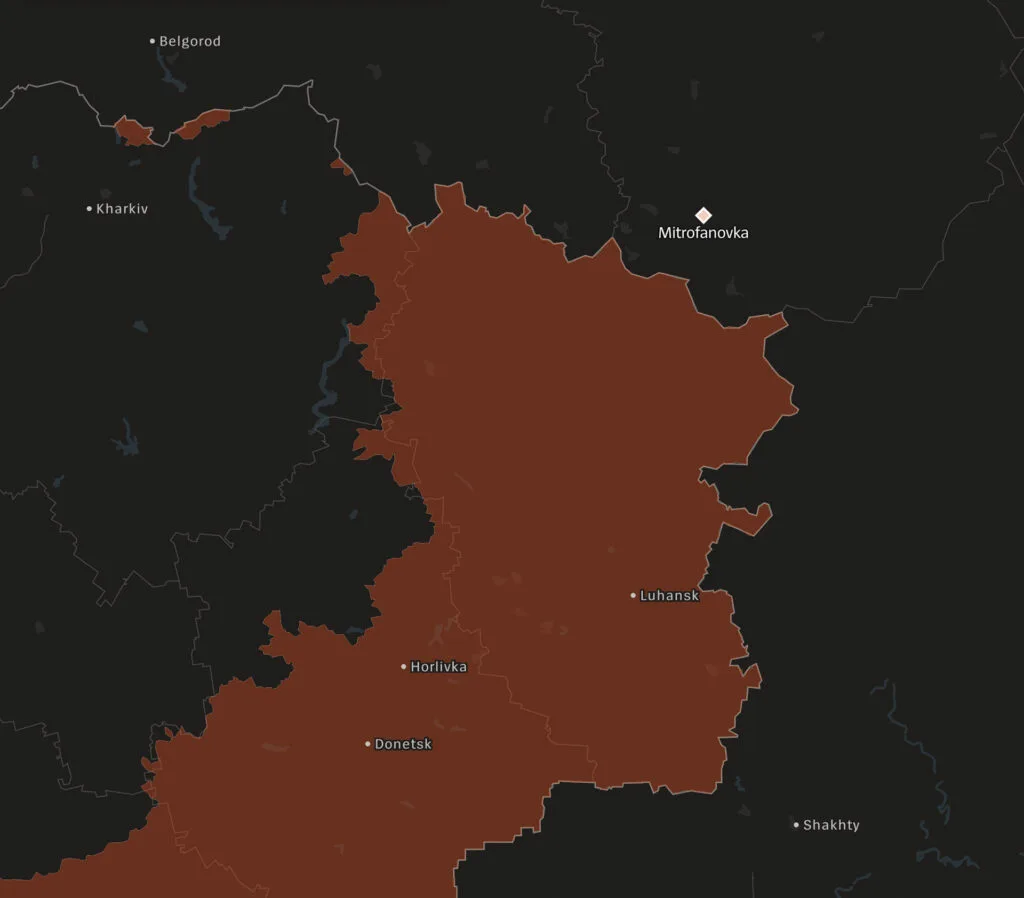

Marsalek, 45, has also traveled on several occasions to the Crimean Peninsula, according to travel records. And he has even ventured to the Russian-Ukrainian front as a fighter, according to security services sources in Moscow.

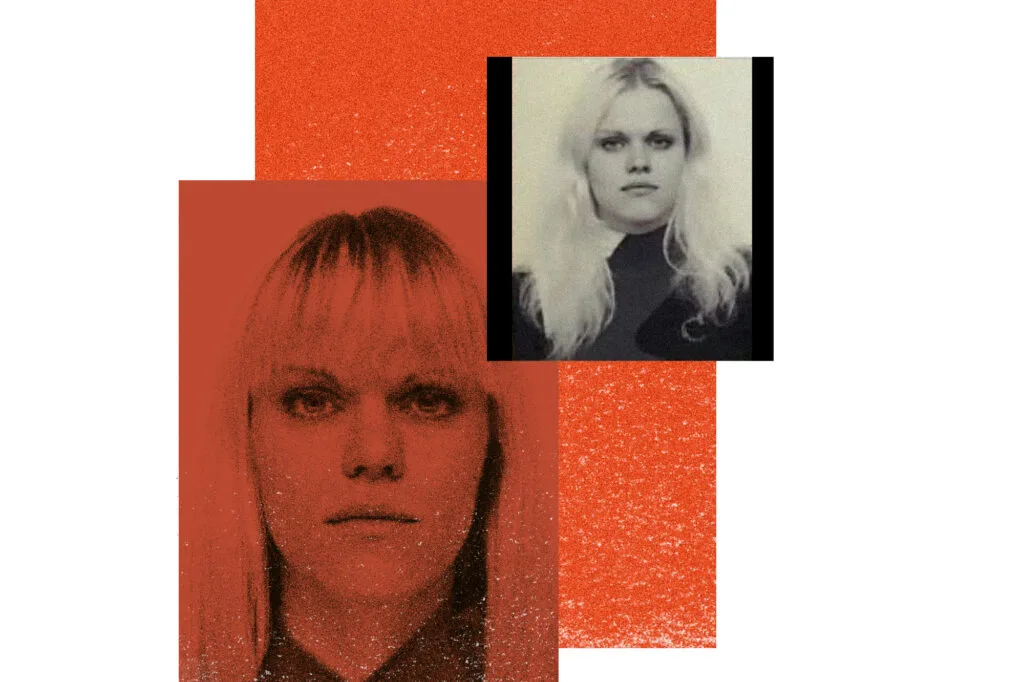

The reporting team was able to piece together Marsalak’s life by also looking closely at his 41-year-old girlfriend, Tatiana Spiridonova.

Spiridonova, a slim and athletic woman with reddish-blonde hair, has a degree in Oriental studies and a wide network of associates. She is active in the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society, for example, which was founded in 1882 to foster relations between Russia and the Middle East. The group, however, is primarily an instrument of Russian intelligence, according to Western intelligence and law enforcement officials. The chairman of the society was once the director of the FSB.

Spiridonova’s ties to the Russian state are documented in data leaked from a database of citizens who have applied for electronic passports. According to her profile in the database, she held a diplomatic passport for several years with clearance to access confidential information up to the “top secret” level.

Tatiana and Jan, the Agent Couple

By at least 2021, Spiridonova and Marsalek had been connected through a central player in the Russian secret services, Stanislav Petlinsky, based on a review of leaked telephone and Russian travel records.

Petlinsky was responsible for recruiting Marsalek as a Russian agent a decade earlier, according to reporting by DER SPIEGEL. And before German authorities had even issued an arrest warrant for Marsalek after Wirecard’s collapse, Petlinksy arranged a private jet to take him from Germany to Belarus, where Russian agents met him and then took him to Moscow. Once there, Marsalek was outfitted with a passport using the identity of a Russian Orthodox priest.

Since Marsalek’s escape, German law enforcement officials said they had been hopeful that he was searching for the missing Wirecard billions and would eventually return and be captured. But in reality, the former executive was busy establishing a new life with the help of associates linked to Russian intelligence services. His most important contact, the team of reporters discovered, was Stanislav Petlinsky.

In February 2024, DER SPIEGEL reporters met with Petlinsky in Dubai. During that meeting, he denied that Marsalek had ever been recruited for the Russian secret service. But Petlinsky spoke openly about Marsalek and their relationship, describing him as “super precise, a bit autistic really.”

“Human relationships are not Jan’s biggest strength,” Petlinsky said. “He lacks empathy.”

Soon after the meeting with Petlinsky, the team uncovered leaked telephone and travel records showing multiple links between him and Spiridonova.

Marsalek and Spiridonova appeared to work well together as a team. In 2022, they set their sights on infiltrating the communications of powerful Austrians using a spy network European investigators say Marsalek had established in Vienna. Through an intermediary, Marsalek’s helpers were able to steal the smartphones of three high-ranking officials from the Austrian Interior Ministry.

On June 10, 2022, a courier dispatched by Marsalek took possession of the three mobile phones in Vienna. From there, the phones were brought to Istanbul. The path of the phones can be traced through chat logs seized by the U.K. Metropolitan Police anti-terrorism unit, as well as leaked Russian flight and phone data. One day after the courier received the phones, Spiridonova traveled to Istanbul from Moscow, the leaked data shows. “The girl just landed,” Marsalek wrote to the courier that same day, according to a chat log obtained by DER SPIEGEL. The next day, Spiridonova flew back to Moscow with the three phones.

A similar operation appears to have been carried out a few months later. Chat logs obtained by British investigators and travel records and data examined by the reporting team show that Spiridonova couriered an item held by the Vienna-based spy network from Istanbul to Moscow yet again — this time a laptop with German security technology.

The day before Spiridonova arrived in Istanbul, Marsalek sent a message to a contact about his girlfriend’s arrival. “Where should my girl go after she has landed?” he asked. Afterwards, Marsalek seemed to report on the operation’s success in another chat message. The laptop, he wrote, is “in a car on its way to Lubyanka,” a reference to the square where the FSB headquarters is located. British authorities later released the messages to journalists. Leaked cellular phone metadata show that Spiridonova’s phone moved from Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport directly to the FSB headquarters and remained there until past midnight.

Marsalek and Spiridonova appear to have grown closer over time. Spiridonova was married when she first met Marsalek, but then separated from her husband. By mid-2021, the two were taking trips together to holiday destinations — Marsalek using a number of fake identities — around the country, sometimes accompanied by Spiridonova’s teenage son. Court documents show that her divorce was finalized in early April 2022.

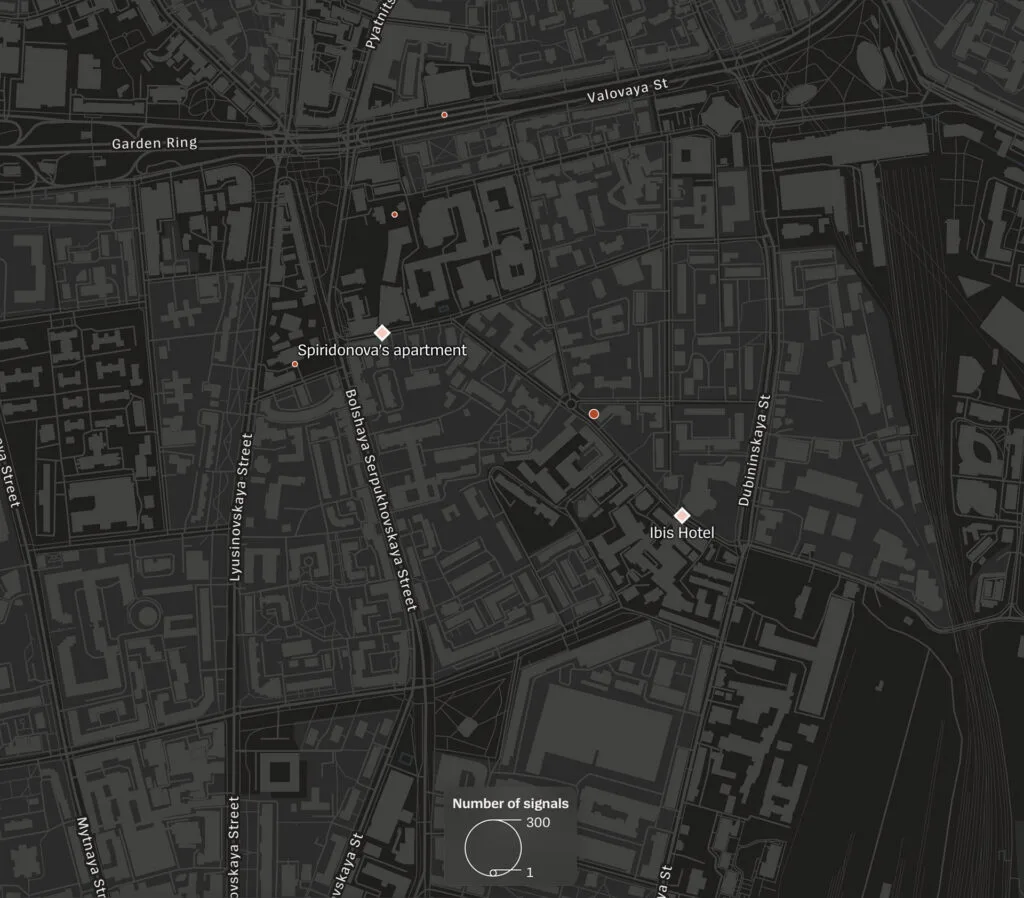

Spiridonova’s small apartment is located south of Moscow’s city center in an unremarkable neighborhood. The plaster is crumbling from the white and yellow facade of the pre-war building. There is a yoga studio in the courtyard and an economics university kitty-corner across the street.

Leaked surveillance footage from the apartment complex shows Marsalek visited frequently. He dropped by on June 13, for example, and then again two days later on June 15. The surveillance camera is built into the building’s steel doorway and provides high-resolution images: Marsalek in front of the door last fall in a wool cap and scarf; him, last summer, with his beard freshly trimmed and a smile on his face, looking upward.

It was too dangerous for the reporting team to try to meet Marsalek or Spiridonova in Moscow. Neither of them would provide comments for this story despite multiple attempts to reach them. Marsalek’s lawyer would also not respond to detailed questions sent to him.

Fake Identity

On July 3, 2023, Spiridonova flew back to Moscow with her 15-year-old son from the Russian spa town of Mineralnye Vody in the Caucasus. Records show that someone named Alexander Nelidov was with them. According to passport information, Nelidov is 47, was born in the then-Soviet city of Riga, and now lives in Moscow. In reality, though, an elderly woman lives at that address.

Publicly available passport databases reveal other inconsistencies. Nelidov’s passport entry is relatively new, issued on June 5, 2023. The passport database says that he is Ukrainian and recently received Russian citizenship. But a review of Ukrainian citizenship records shows that there was never an Alexander Nelidov in Ukraine. Furthermore, the photo on a scan of the passport obtained by “The Insider” clearly shows Jan Marsalek.

Nelidov, the reporting has found, is just one of at least six identities Marsalek uses. On two occasions, he has taken over the documents of Russian priests he resembles. He also has a falsified passport from Belgium issued in the name of Alexandre Schmidt. But the photo, once again, is of Marsalek.

Marsalek seems to rotate his identities when he travels, but the team was able to track him using a variety of sources, including Spiridonova’s movements. On Dec. 28, 2024, she took a train from Moscow to St. Petersburg, departing at 8 a.m. Alexandre Schmidt is listed as also being on board the train, according to passenger data from a leaked booking system.

That system is just one of many sources of data that are regularly leaked in Russia. Along with hacked information siphoned off the internet, the leaks are a trove for reporters — and have been crucial in helping trace Marsalek.

After uncovering Marsalek’s secret Nelidov identity, the reporting team was able to find a mobile phone number that he apparently uses. It is listed in several different databases, including flight booking contacts and insurance records.

Calling Marsalek

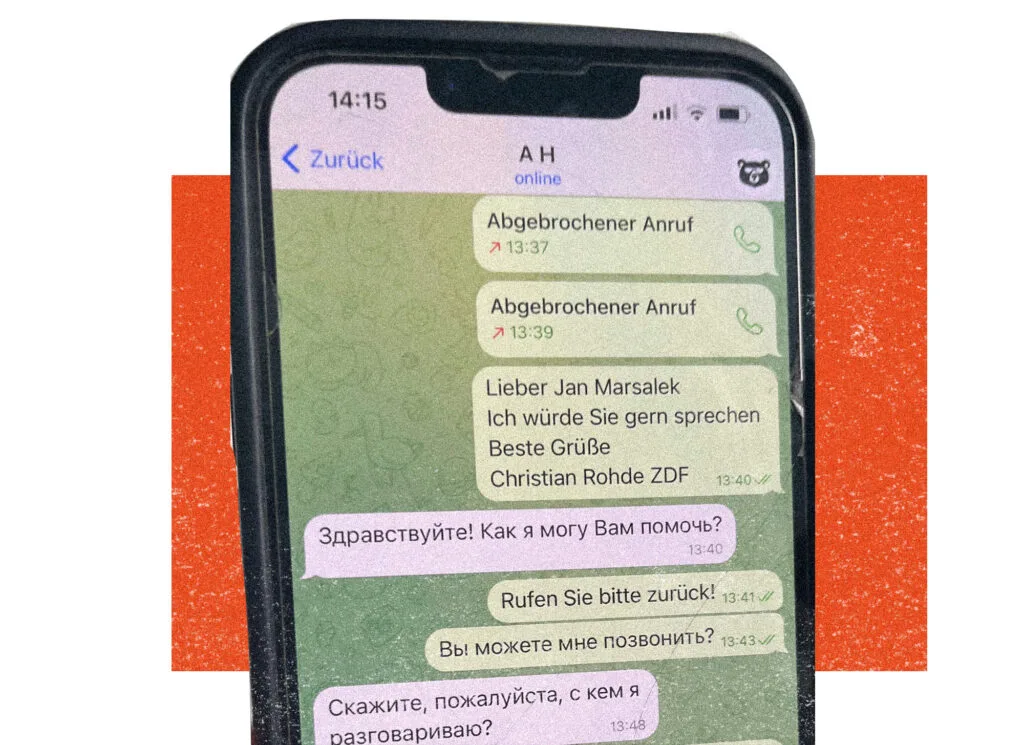

The phone number was the decisive lead the reporting team had spent years pursuing — the opportunity to establish direct contact with Marsalek. In early September 2025, reporters from DER SPIEGEL and ZDF called the number through the messaging app Telegram. The profile photo of the account showed a cartoon bear wearing sunglasses. The phone rang, but someone declined the call at the other end.

The reporters then tried to establish contact via text messaging. The answer arrived in Russian after five minutes. “Tell me who I’m talking to, please?” A journalist introduced himself and asked for Jan Marsalek or his alias, Alexander Nelidov. The response: “You have made a mistake.”

But the chat didn’t end there. In one message, he asked what the journalists wanted to talk about. DER SPIEGEL and ZDF responded that they wanted to discuss the well-publicized accounts of Marsalek spying on investigative journalists Christo Grozev and Roman Dobrokhotov — two members of the reporting team, whose stories are chronicled in the FRONTLINE documentary, Antidote. After a long pause came the terse answer: “Very interesting characters.”

The chat went back and forth a few times and the reporters then asked whether this person, thought to be Marsalek, wanted to speak on the phone. “A very interesting offer,” came the response. Then, the exchange broke off.

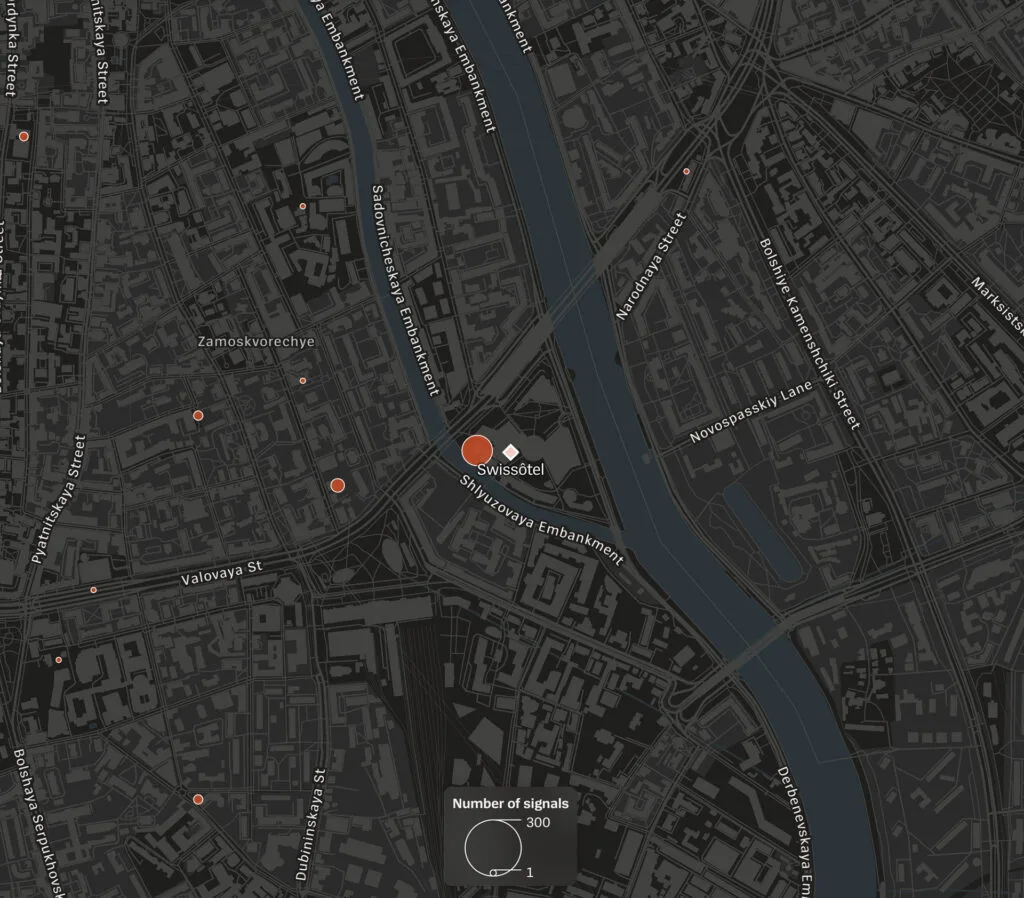

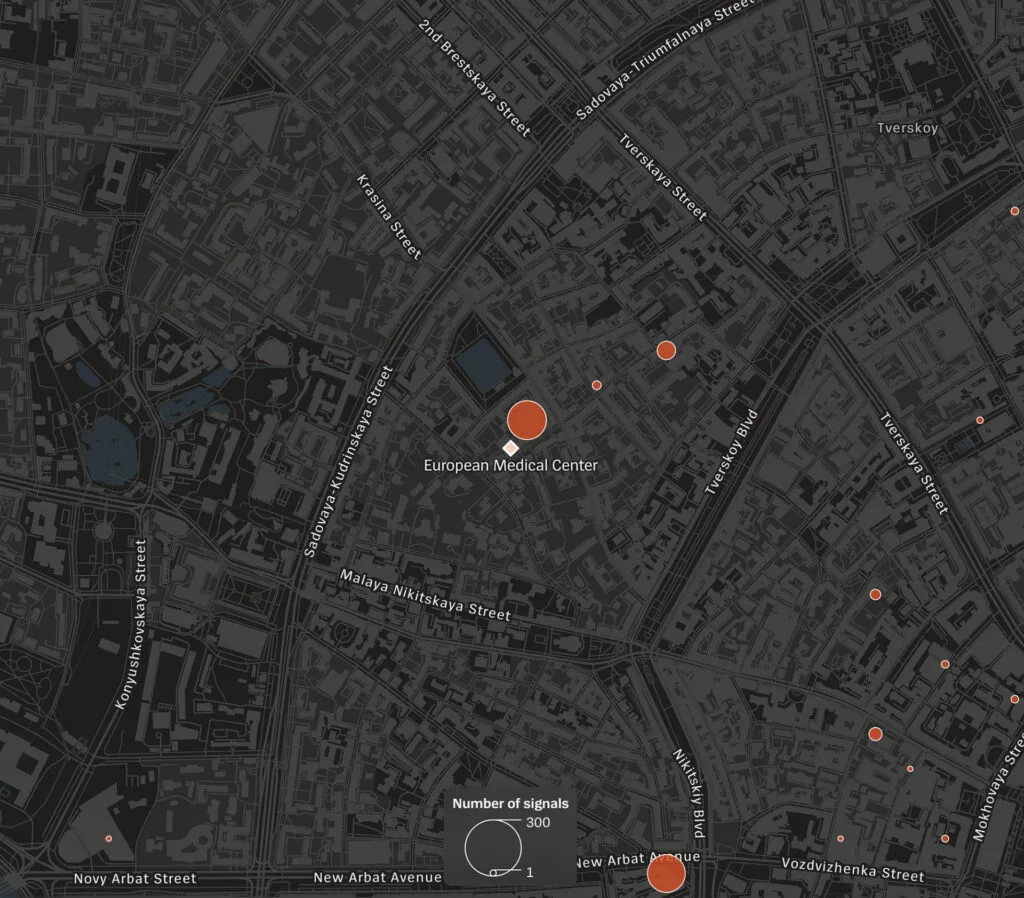

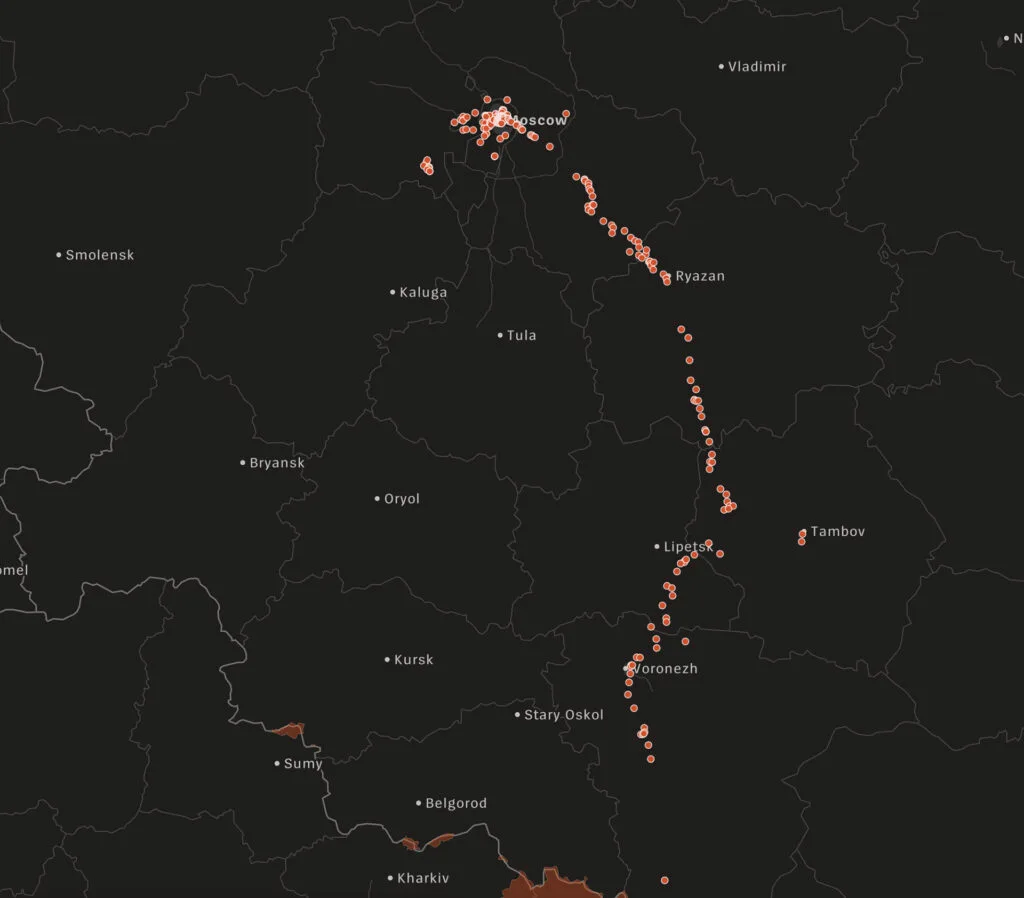

A cache of leaked location data, which recorded a cell tower’s position every time Marsalek’s phone connected to the network, provided the reporting team with a detailed map of his movements. Combined with the team’s other reporting, these digital breadcrumbs revealed a new, grounded lifestyle more akin to that of a middle-class Muscovite than a high-flying millionaire.

Not every single registration of the telephone on Lubyanka Square corresponds to a visit to the FSB. But the available data and photographs obtained by DER SPIEGEL suggest Marsalek was a frequent visitor there.

In order to protect the photographers, certain images can only be described and not released publicly. They show Marsalek on several days in 2025 near FSB headquarters during normal office hours.

Where Does Marsalek Live?

It was not possible to pinpoint where Marsalek lives. The address on the western outskirts of Moscow included in the Nelidov passport data seems not to belong to him.

Marsalek has also frequented a luxury hotel in Moscow.

In the War Zone

More consequential than cosmetic concerns, however, appears to have been a trip to the war zone in Ukraine.

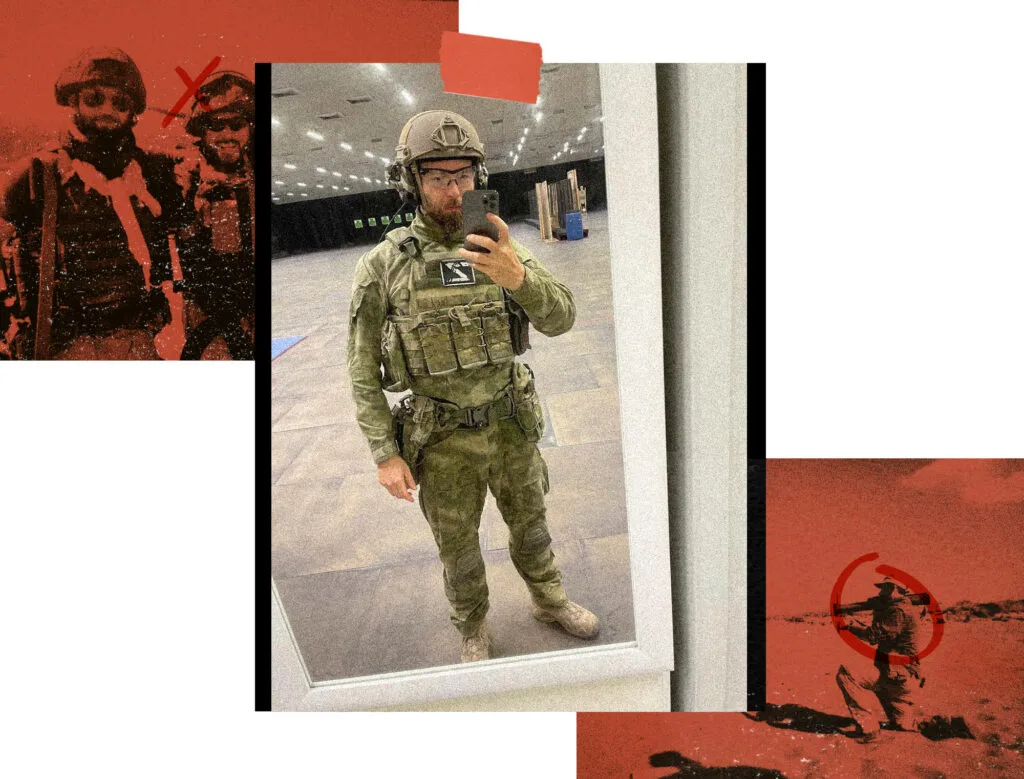

A photo released by British police shows the former Wirecard executive in full military combat gear, complete with a helmet and a “Z” sewn onto his body armor, the emblem of the Russian war in Ukraine.

And there is also leaked information from Russian border guards indicating additional trips taken by Marsalek to the front. On Nov. 22, 2023, a system that records border crossings showed Alexander Nelidov crossing into Russia from the Ukrainian city of Mariupol. The image stored in the system is of Jan Marsalek.

He also seems to have made at least five train trips from Moscow to the Crimean Peninsula — grueling journeys, each taking 28 hours, one way.

A close look at the passenger data, including booking times and positions of seats, indicates who Marsalek was traveling with. On one trip was a member of Spetsnaz, the Russian special forces.

Germany’s federal prosecutor general is officially investigating Marsalek for espionage activities. And criminal investigators in Munich along with the Federal Criminal Police Office have been trying for years to bring him into custody for the suspected Wirecard fraud. But when it comes to Marsalek’s activities in Russia, police officers and intelligence agents alike have limited visibility.

Read DER SPIEGEL’s version of the investigation in German.

The tools available to them are largely limited to classic methods of policework. They are allowed to listen in on unencrypted telephone conversations, which Marsalek almost never engages in. They are allowed to maintain surveillance on friends and relatives of the fugitive, who Marsalek apparently doesn’t visit. They are able to search through social media accounts, which Marsalek apparently doesn’t use.

Clueless Agents

DER SPIEGEL has learned that it has been challenging for the criminal investigators in Munich to work with German intelligence agencies on the Wirecard case. “They aren’t interested in the case,” said a Bavarian official who requested anonymity.

The fact that Marsalek left for Belarus in summer 2020 and, from there, headed to Russia is something that German security officials have privately said that they learned from DER SPIEGEL. In a joint reporting project with the investigative platform Bellingcat and “The Insider,” DER SPIEGEL that year obtained data from Belarus’ entry register confirming that Marsalek had crossed the border. German intelligence had no access to the data.

Germany’s intelligence chiefs have said little publicly about their efforts to track Marsalek. It was long said behind closed doors that Marsalek is a white-collar criminal, not necessarily a target for intelligence services.

At various public places in Bavaria — where Wirecard was headquartered — and throughout Germany, passengers are confronted with a wanted poster showing Marsalek, listing it as a cold case.

Nevertheless in 2021, German authorities ultimately submitted a legal assistance request to Moscow. The reply came quickly: Russian authorities claimed to have no knowledge of Marsalek’s presence in the country. Berlin, Russia suggested, should ask in Kazakhstan; he may have been seen there. Since then, all judiciary-level interactions with Vladimir Putin’s government have ground to a halt.

Not long after Marsalek’s escape following the Wirecard scandal, Wolfgang Schmidt, the chief of staff of the Chancellery at the time, tried to get Marsalek’s name added to a secret list of captured spies, dissidents and jailed journalists whom the West was hoping to swap with Russia. The German authorities were hopeful he would be extradited in exchange for Vadim Krasikov, the man who murdered a former Chechen commander in Berlin in 2019 and was sent to Moscow in exchange for opposition activists, a former U.S. soldier and the reporter Evan Gershkovich. But the Kremlin ignored the effort.

For now, some German officials say the greatest likelihood of Marsalek facing justice is if he turns himself in, or if a globally circulated Interpol notice might finally yield results. “Maybe he’ll take a trip one day and be recognized,” one German official told DER SPIEGEL. “We can wait.”

In the meantime, an espionage trial in the United Kingdom underscores just how dangerous Marsalek might be. In March 2025, the Central Criminal Court in London convicted a six-member group from Bulgaria for spying on Russia’s behalf between summer 2020 and February 2023. Scotland Yard’s investigations say that Jan Marsalek was the group’s mastermind and handler. According to statements made in court by investigators, he was working on behalf of the FSB, but also occasionally for the GRU, Russia’s military secret service.

The primary perpetrator in the case was a Bulgarian named Orlin Roussev, a business contact of Marsalek’s from Wirecard. On Marsalek’s instructions, Roussev and other Bulgarian confidants assembled a group of at least six agents based in London and Vienna. Around 100,000 revealing text messages between him and Marsalek were later found on Roussev’s confiscated mobile phone. Investigators used the texts and other evidence to expose numerous operations undertaken by the cell.

Read DER SPIEGEL’s account of how the investigation was carried out (German).

In fall 2022, for example, the group conducted surveillance of a U.S. military base in Stuttgart, Germany. British counterespionage agents ended up discovering the group, and in February 2023, police raided several apartments in England and made five arrests, with a further cell member arrested a year later. According to court documents, a raid of Roussev’s home found 495 SIM cards, more than 200 telephones, 258 hard drives, 11 drones, 75 different passports and numerous listening devices, some of them hidden in everyday items like toys or neckties. The chats recovered from Roussev’s devices as well as those from the five other Bulgarians presented the U.K. police with a clear chain of command: Marsalek initially recruited Roussev as the point man for clandestine operations for Russia’s intelligence services; Roussev in turn recruited the other Bulgarians and tasked them with missions across the continent — ranging from surveillance of journalists (including two members of this reporting team) and conducting false-flag campaigns aimed at discrediting Ukraine, to spying on a U.S. military base in Germany and preparing Russian dissidents wanted by the Kremlin regime for rendition.

Several digital copies of falsified identification documents were also found during the arrests. Including a Belgian passport issued to “Alexandre Schmidt” bearing Marsalek’s photo.

Codename “Red Sparrow”

Chat logs used in the U.K. court case reveal Marsalek talking about kidnapping and even murder. “We have to kidnap someone and bring him back to Russia,” he wrote to Roussev in September 2021. He was specifically interested in a former Russian security official who had fled to Montenegro. “It doesn’t matter if he dies by accident,” Marsalek continued, “but it would be better if he made it to Moscow.”

The Bulgarian agents tasked by Roussev traveled to Montenegro in fall 2021 and spent weeks conducting surveillance on the former official. In the end, the attempted kidnapping was unsuccessful, and the former Russian official is today hiding at an unknown location.

During the operation in Montenegro, another key player in the Marsalek story was on the scene: a shadowy FSB spy referred to in text messages between members of the group as “Red Sparrow.”

Extensive reporting by DER SPIEGEL and other journalists have found numerous links between the person known as “Red Sparrow” and a Russian woman, Evgeniya Kurochkina.

Her name and phone number appear in leaked documents as the person who applied for the Russian passport Marsalek used in his escape from Germany after the Wirecard scandal. And according to leaked phone and border crossing records, Kurochkina regularly called and traveled with an FSB agent from Moscow. The data also reveals that Kurochkina brought Marsalek to his hiding place on the Crimean Peninsula shortly after his escape.

Almost a year and a half later, on Dec. 28, 2021, according to chat data, the Bulgarian team tasked with carrying out the Montenegro kidnapping were expecting the arrival of “Red Sparrow.” According to Russian flight data, Evgeniya Kurochkina was also booked on a flight from Moscow to the Balkans on Dec. 28, 2021.

Kurochkina would not respond to repeated attempts to contact her. According to her resume, she had worked since 2006 as a personal driver and bodyguard for business leaders and for a former member of the Ukrainian government. Under special skills, the resume lists “hand-to-hand combat” and “training in handling firearms.” Personal photos obtained by the reporting team show Kurochkina undergoing training with a submachine gun.

And there is one other key detail about Kurochkina that emerges in the leaked chats: she served as a bodyguard, driver and aide to Stanislav Petlinsky, Marsalek’s contact within Moscow’s intelligence network.

Journalists Under Threat

Although Marsalek and his associates would not speak for this story, they have had two members of the reporting team in their sights for years: Christo Grozev and Roman Dobrokhotov.

Grozev spent years as the chief reporter for the investigative platform Bellingcat and now also works for DER SPIEGEL. As detailed in FRONTLINE’s Antidote, he has attracted attention and faced dire consequences for his exposés on the Kremlin and its actions.

Roman Dobrokhotov is the editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative outlet “The Insider.” He, too, is seen as an enemy by the Russian government, and four years ago, he fled to Europe. Moscow has issued a warrant for his arrest.

Marsalek’s hired agents have repeatedly shadowed the journalists. In Vienna, they used cameras to conduct surveillance on Grozev and his family from an apartment they had rented across the street. In leaked chatlogs, Marsalek and Roussev, the Bulgarian team leader, considered the possibility of kidnapping and detaining Grozev to gain access to his phone and laptop.

Listen to DER SPIEGEL’s podcast episode about the investigation.

The men even chatted about the possibility of murdering the reporter. Using an axe for such a murder, Marsalek wrote in a message to the Bulgarian gang leader in December 2022, was too archaic. “Better is a sledgehammer, Wagner style,” a reference to Russian mercenary force Wagner Group. But Marsalek ultimately discarded the idea of murdering Grozev. It would likely only lead to problems, he told the gang leader. The plot was ultimately discovered by MI5, the British domestic intelligence agency, and became an important factor in the London trial.

According to British court documents, Marsalek paid at least 100,000 euros to his associate, Roussev and the Bulgarian gang. The money was disguised through accounts belonging to shell companies, according to the court records, and at least some of it came from the Russian secret service. But it is still not known where the rest of the money came from.

Vanished Billions

The Wirecard scandal is first and foremost a finance scandal. Wirecard, which grew to become an international financial giant, was long considered to be the financial services provider of the future and, for a time, was more valuable even than Deutsche Bank. But under Marsalek, the company constructed a system of opaque channels that was perfect for money laundering. Multi-billion-euro transactions for clients were processed outside of Wirecard, but the revenues were listed on the company’s balance sheet, and the supposed commission earnings were recorded in trustee accounts — which is why no one realized for quite some time that billions of euros in Wirecard funds were not actually in the accounts where they were supposedly held. That money still hasn’t been found today.

There are traces. They lead to Singapore. To Switzerland. To Scotland. And to Russia.

In Moscow, not far from the FSB headquarters is a branch of Transkapitalbank. The U.S. Treasury Department has described the institution as the “heart” of Russia’s sanctions-evasion network.

A cell tower stands less than 60 meters from the bank. Between the end of January and the end of May 2024, Marsalek’s phone was registered there 103 times over a period of seven days.

The story of Jan Marsalek is far from over. Many questions remain, including: where is the money?

Editor’s note: Since the initial publication of this story in Europe, Austrian authorities have said they’re considering revoking Jan Marsalek’s citizenship based on the revelations that he is living in Russia, spied for Moscow and joined Russian forces in Ukraine.

Related Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Related Stories

Related Stories

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.