Strike on Iran: The Nuclear Question

December 16, 2025

54m

An investigation of Iran’s nuclear program in the aftermath of U.S. and Israeli strikes

Strike on Iran: The Nuclear Question

December 16, 2025

54m

Share

Using rare on-the-ground access in Iran and in-depth forensic analysis, FRONTLINE, The Washington Post, Evident Media and Bellingcat conduct an immersive investigation of Iran’s nuclear program in the aftermath of the U.S. and Israeli strikes.

An updated version of this documentary will premiere on March 31, 2026.

Directed by

Produced by

Correspondent

Transcript

Credits

Journalistic Standards

Support provided by:

Learn More

Most Watched

The FRONTLINE Newsletter

Killing the ‘Brain Trust’: How Israel Targeted Iran’s Nuclear Scientists

‘Strike on Iran’ Filmmakers Were Closely Monitored as They Filmed in Iran for Two Weeks

Related Stories

After U.S. Strikes, Iran Increases Work at Mysterious Underground Site

Exclusive: Iran Won’t Allow Nuclear Inspections if Sanctions Are Reimposed, Says Iran’s Chief Nuclear Negotiator

Killing the ‘Brain Trust’: How Israel Targeted Iran’s Nuclear Scientists

Inside the Discovery of New Activity at Pickaxe Mountain, Iran’s Deep-Underground Suspected Nuclear Site

‘Strike on Iran’ Filmmakers Were Closely Monitored as They Filmed in Iran for Two Weeks

The U.S.-Israel War With Iran: 5 Documentaries & a Podcast Episode Help Explain the Backstory

Investigating Iran’s Nuclear Ambitions

The Escalating War With Iran

Related Stories

After U.S. Strikes, Iran Increases Work at Mysterious Underground Site

Exclusive: Iran Won’t Allow Nuclear Inspections if Sanctions Are Reimposed, Says Iran’s Chief Nuclear Negotiator

Killing the ‘Brain Trust’: How Israel Targeted Iran’s Nuclear Scientists

Inside the Discovery of New Activity at Pickaxe Mountain, Iran’s Deep-Underground Suspected Nuclear Site

‘Strike on Iran’ Filmmakers Were Closely Monitored as They Filmed in Iran for Two Weeks

The U.S.-Israel War With Iran: 5 Documentaries & a Podcast Episode Help Explain the Backstory

Investigating Iran’s Nuclear Ambitions

The Escalating War With Iran

Tehran, Iran

September 2025

SEBASTIAN WALKER, Correspondent:

I’m in Tehran, at a spot where weeks ago a top Iranian nuclear scientist was assassinated in an Israeli strike. The blast took out the side of this building. It was one strike in an unprecedented U.S. and Israeli air campaign.

BENJAMIN NETANYAHU:

We were facing an imminent threat. A dual, existential threat.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Hundreds of munitions launched in the span of days, aiming to cripple Iran’s nuclear program.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP:

Iran’s key nuclear enrichment facilities have been completely and totally obliterated.

AYATOLLAH ALI KHAMENEI:

[Speaking Farsi] … behind those words lies another truth, that they failed to achieve their intended goal.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Iran fired back, launching barrages of ballistic missiles and drones into Israel.

I’ve reported from Iran before, and foreign journalists especially are always closely monitored. This time, it’s even more so. The government is tightly controlling where we go and who we can talk to. But it’s a chance to see some of the damage up close, to sit down with top officials—

How much has this set back Iran’s nuclear program?

ALI LARIJANI, Sec., Supreme National Security Council:

[Speaking Farsi] Iran’s nuclear program can never be destroyed.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

—and to try to understand the scale of the operation and the question of what it left behind.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

It’s Friday prayer at the Tehran University campus.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

The imams here are handpicked by Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and they echo his message: that the 12-day war in June didn’t devastate the country’s nuclear program, as the U.S. and Israel have stated.

IMAM MOHAMMAD JAVAD HAJ ALI AKBARI:

[Speaking Farsi] Our hearts fill with sorrow as we read the names of the dead alongside the names of so many martyred scientists and academics.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Instead, they say, the bombing has drawn Iranians closer together and hardened their resolve against their mortal enemies.

IMAM MOHAMMAD JAVAD HAJ ALI AKBARI:

[Speaking Farsi] God willing, with the guidance of our martyrs, warriors and commanders, the nation of Iran will continue down this glorious path.

CROWD:

[Speaking Farsi] God is great! Death to Israel! Death to the United States!

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

We’ve been given permission to film here—accompanied by our minders. It’s the kind of scene that Iran’s hardline theocratic government often wants to project to the outside world. But halfway through the sermon, we’re told we have to leave, a sign of the constant challenges we’ll be facing.

My journey started two weeks earlier in the newsroom of The Washington Post. Given the limitations of working inside Iran, we partnered with the Post’s visual forensics team to help guide the reporting on the ground, and we worked with investigative journalists from nonprofit outlets Bellingcat and Evident Media.

The team has been poring over satellite imagery to understand from afar the impacts of the strikes and how much the nuclear program has been set back.

Nilo Tabrizy speaks Farsi and has been combing social platforms accessible in Iran for images and video of the locations that were hit.

We’ve been told we can get access to the site of an assassination and also speak to family members of a killed scientist.

NILO TABRIZY, The Washington Post:

That would be really helpful to us, because we were only able to confirm about five of these names with their locations. I think we’ve gotten close to exhausting what we can do from afar, and this is really where the field reporting is going to come in handy.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Eric Rich is the Post’s deputy investigations editor.

ERIC RICH, The Washington Post:

It would be great if we could coordinate while you’re there. As you start to get a sense of which scientists’ families you might be able to talk to, let us know immediately and we can start to build a dossier around that strike. Also, if anybody is able to share photos that they may have on their phones from immediately after, that would obviously be of even greater interest.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

So sending pictures back, sending videos back, that’s something that’s helpful?

ERIC RICH:

That would be hugely helpful. And we can in real time, we can analyze them and try to understand if we can draw some conclusions or inferences that might shape questions for the questions that you can ask.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Prior to the strikes, the International Atomic Energy Agency had said that Iran had increased its stockpile of near weapons-grade enriched uranium, though hadn’t found evidence of a systematic nuclear weapons program.

But Israel believed Iran was just a short step away from producing a nuclear bomb, which they saw as an existential threat. They seized the moment.

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

We’re hearing a statement from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

BENJAMIN NETANYAHU:

Moments ago, Israel launched Operation Rising Lion to roll back the Iranian threat to Israel’s very survival.

AL JAZEERA NEWSREADER:

In and around the capital, Tehran, Israeli targets seem to be expanding.

MALE NEWSREADER:

The Iranians acknowledging that some of their senior military leaders have been killed or wounded.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

The first wave of attacks hit nuclear facilities, military targets and apartment blocks in Tehran.

Our government minders have brought us to one of the locations that was hit, a building we’re told is known as the “Professors’ Complex” since many academics live here.

We’re shown around by Iraj Rasooli, a microbiologist, and his relative Hanieh.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Whoa, it’s still falling down.

IRAJ RASOOLI:

Yeah. Just be careful.

Sixth floor was hit. Where we are standing is third floor. Four, five and one above that, six. From ninth floor to third floor: 100% destruction.

I was sleeping there. That was my bedroom. My elder daughter was sleeping here, younger daughter was sleeping there. So when I went to help her brother, he was thrown from his bed, here he was sleeping, to that corner. So when I went to help him, to lift him up, so his entire skin came on my hand. It was so bad. He was so badly burnt.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Rasooli says his son-in-law died. So did his daughter and grandson.

Living three floors above them was a physics professor named Mohammad Tehranchi. Sanctioned by the U.S. in 2020, he was seen by Israel as a key player in Iran’s pursuit of a nuclear weapon.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Did you know the person that they were targeting?

IRAJ RASOOLI:

Yeah, yeah.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

You knew him personally?

IRAJ RASOOLI:

I knew him, yeah, I knew him.

HANIEH:

He knew, but he didn’t know that he is an important person for the government.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

You didn’t know that he was doing this this role in the program?

IRAJ RASOOLI:

We knew that he was a physicist, and he was chancellor of Islamic Azad University. We knew this much. So what Israel knew more than us, that is up to them. We don’t know. We don’t know.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Hey, so I just wanted to send a voice note. We’re at a building in the north part of Tehran. This is the site of one of the killings of one of the scientists. We’re on the floor below where his apartment was, and I think there were six floors that are missing here, so the size of the munition that was used was extensive. There were civilians killed alongside this scientist. This is Dr. Mohammad Tehranchi. He’s a professor of physics at one of the universities, and the residents here say that they didn’t really have any sense that he was associated with the nuclear program.

Another strike in Tehran less than two hours later killed a scientist named Fereydoun Abbasi, who used to head the government agency that runs Iran’s nuclear program. He had been sanctioned by the U.S. and EU and survived an assassination attempt in 2010 widely attributed to Israel.

As we travel around Tehran, we see posters of both men celebrated as martyrs. Both Abbasi and Tehranchi were buried alongside top military commanders also killed in the Israeli strikes. Thousands attended the funerals.

We’re given permission to visit the site of Tehranchi’s grave, to see if we can find out anything more about him. Almost three months after the strikes, people are still coming to pay their respects to those killed by Israel. We approach a man who says he comes here once a week to pray for Tehranchi.

MALE MOURNER:

[Speaking Farsi] We had one Tehranchi, and this will create hundreds of Tehranchis. Maybe I, myself, might lack the knowledge, but I can encourage my children to pursue this field so that they can complete the work that he started and continue his legacy.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Our conversations are helping the Post develop a picture of the importance of Tehranchi and the other scientists killed.

ERIC RICH:

So he seems like a really critical character in this. Do we have any sense of whether he and the others were targeted for their specific expertise or a specific project that they were working on that was part of the alleged nuclear program?”

NILO TABRIZY:

I talked about this with a few different sources, about how important are these guys, and someone mentioned they went after older scientists. None of these were younger people in the field. And so this one expert said it’s probably because they want to try to destroy the brain trust, the people who are foundational in this. But the other side of it is that for the past decade or so, maybe even longer, there’s been a big push in Iran apparently to have people train and study up in theoretical physics and nuclear work.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

We repeatedly ask our minders if we can speak to relatives of the assassinated scientists, who Israel claimed were leading Iran’s nuclear program. They finally agreed to introduce us to Tehranchi’s brother, Amir

So how would you describe his role in Iran’s nuclear program?

AMIR TEHRANCHI:

[Speaking Farsi] Dr. Tehranchi, given his expertise, wasn’t directly involved in this field. But he might have been managing a nuclear project providing some interdisciplinary insights. Some fields could be related to each other based on nuclear science. After all, he was mainly a physics professor.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

So the U.S. says that he played a leading role in efforts to develop a nuclear device in the mid-2000s, up to 2003. What’s your response to that?

AMIR TEHRANCHI:

[Speaking Farsi] In my opinion, he dealt with electromagnetics and not nuclear science. This project doesn’t involve killing human beings. There are many countries in the world that have pursued such projects. Iran also gained access to this knowledge.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

So he was placed on the list of sanctions by the U.S. government. Were you surprised when this happened?

AMIR TEHRANCHI:

[Speaking Farsi] No, it wasn’t important at all. He described the sanctions as oppression by the United States.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

For people outside of Iran who are questioning how much these killings have set back Iran’s nuclear program, how big a loss do you think it is to have his knowledge, his expertise taken out of the equation?

AMIR TEHRANCHI:

[Speaking Farsi] Looking at the history of Iran, we have always sought to use our knowledge and discoveries to serve humanity, and this includes nuclear science. The knowledge is in the minds of the scientists and students of this field. And with the killing of these professors, they might be gone, but their knowledge isn’t lost to our country.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Hey, I just wanted to send you a quick note because we’ve just wrapped an interview with Tehranchi’s brother. When we were done he showed me photographs that he’d taken that were on his computer. There were what appeared to be fragments of the weapon. Pieces of metal, what looked like rotors, and also there was what appears to be a serial number. He didn’t want to give us the originals, but we’ve filmed it on our camera, and I’ve taken screenshots that I’m going to send to you.

Working with open source investigators from Bellingcat, the Post team starts piecing together how the strikes against the scientists were carried out and looking into whether the Israelis used some kind of “special weapon,” as had been reported in the Israeli media.

ERIC RICH:

So, were there markings on the alleged fragments, or we couldn’t make it out?

TREVOR BALL, Bellingcat:

Yeah, there were some markings on there that had a possible part number and a possible lot number. You have SMBAMS004A. But with a lot of these databases are private from the arms company, so it’s not something we can check using open sources, especially if it’s a weapon that hasn’t been used before.

ERIC RICH:

Trevor, is there anything at the strike site that allows us to glean any insight into whether this munition was fired from an aircraft or the ground?

TREVOR BALL:

So from the damage alone, the experts we talked to, they weren’t able to confirm that. It’s more likely that it was a longer-range munition like a ballistic missile or a cruise missile.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

In Tehran, we’re pushing to see more strike sites. Our minders agree to take us to where another nuclear scientist was killed. We’re told it happened within minutes of the Tehranchi strike.

The timing of the assassinations seems coordinated so that none of the targets had time to go into hiding.

We’re at another location here. It’s where the scientist called Ahmadreza Zolfaghari was killed. A local resident told us that she heard the explosion at around 3:30 a.m., so almost the exact same time that the other strike took place.

Ahmedreza Zolfaghari was the former dean of the faculty of nuclear engineering at the Shahid Beheshti research university, which was sanctioned by the EU and others for links with Iran’s nuclear program.

As night falls, we find a neighbor who lives across the street.

MALE NEIGHBOR:

[Speaking Farsi] I was there, it was nighttime.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Which one is your house?

MALE NEIGHBOR:

[Speaking Farsi] The third [floor].

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

This one?

MALE NEIGHBOR:

[Speaking Farsi] From the parking lot, I heard a noise like voooo. Everything turned orange right away, from the sky to the ground. I looked and I saw the missile went in like this.

MALE VOICE [on video]:

[Speaking Farsi] The building is collapsing! Everyone go! Run!

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

That’s from the same night?

MALE VOICE [on video]:

[Speaking Farsi] Call an ambulance.

MALE NEIGHBOR:

[Speaking Farsi] It was there.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

It’s from there.

MALE NEIGHBOR:

[Speaking Farsi] Right there.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Did you know who was living here?

MALE NEIGHBOR:

[Speaking Farsi] Dr. Zolfaghari, he was a scientist.

I wouldn’t wish this on anyone, Iranian or Israeli citizens alike.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Over the course of several days, we’re taken around Tehran to various locations where Israeli strikes had taken place. We sent pin locations, photos and interviews with witnesses back to the team in the U.S., who combine them with satellite imagery and geolocated video to start to piece together a bigger picture of what happened.

It was an assault at multiple sites across the city. The strikes started in the early hours of the morning and hit in quick succession. Nine people Israel viewed as key to Iran’s nuclear program: scientists, engineers, physicists. All were killed.

We are able to confirm the locations and tally civilian casualties from the strikes on Abdolhamid Minouchehr and Ahmadreza Zalfaghari, both nuclear-engineering professors killed just blocks from each other.

Further east, we confirm the location and casualties from the strike on Mansour Asgari, a physics professor sanctioned by the U.S. for alleged ties to nuclear weapons development.

And in Sa’adat Abad neighborhood, where Tehranchi was killed, witness accounts combined with images of the direction of the blast and structural damage indicate a weapon or weapons with the force of a roughly 500-pound bomb.

Taken together, it reflects an unprecedented campaign by Israel in its scale, weaponry and impact.

June 14, 2025

BENJAMIN NETANYAHU:

We’ve already done great things. We’ve taken out their senior military leadership. We’ve taken out their senior technologists who are leading the race to build atomic weapons that would threaten us, but not only us. We’ve done all that and many other things, but we are also aware of the fact that there’s more to be done.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Washington Post correspondent Souad Mekhennet spent time in Israel interviewing senior intelligence and military sources about the operation. She was able to speak to a senior military intelligence official who helped plan the assassinations, which he said had been years in the making. He let her record the meeting but didn’t want his face shown.

ANONYMOUS ISRAELI INTELLIGENCE COMMANDER:

We mapped out a group of roughly 100 scientists, and we made an extensive analysis. We ended up with a group of the most valuable targets to be eliminated. The second phase was developing the intelligence and operation capability to precisely strike and eliminate each one of these targets, up to the level of an apartment in Tehran. We’ve made everything possible to minimize the collateral damage that is expected and employed precise force only against targets that we thought were critical to deny Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons. Since knowledge is the core asset of any weaponization program, we assess that the elimination of all major nuclear scientists in Iran is a major setback for the project.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

A senior security official told the Post that Israel did use a so-called special weapon for precision strikes against military targets, but wouldn’t get into details. The official also said that they were able to track the scientists and other targets using more than 100 local assets inside Iran.

SOUAD MEKHENNET, The Washington Post:

So apparently, local Iranian assets played a major role in finding out where those scientists were living, if they were still active, where they were active. This apparently is also the first time in the history of Mossad that they led an operation in a foreign country with a majority of local assets. They said they wanted to send a message to the government in Iran, together with the American intelligence services, which was these two would always work together in making sure that Iran would not reach a point where they could create and build a bomb.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

One of the scientists on Israel’s list escaped death that first night. We want to go to the town where he fled, around six hours north of Tehran. The Iranians rarely let international reporters outside the capital.

Our minders agree to take us, but they insist we stop at an airport near Karaj, a city where Iran produces centrifuges that enrich uranium. We’re shown around by an airport official.

What kinds of people would be landing in those planes?

ZAHRA YOUNESI, Airport official:

[Speaking Farsi] Just private individuals. Some people came here for training and others for recreational flights.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

They claim this was a purely civilian site.

The Israeli military said they had no record of a strike here. But the military intelligence official the Post spoke to said all the strikes were against high-value targets in the, quote, “nuclear sphere” and had a military objective.

This is flight logs?

ZAHRA YOUNESI:

Logbook.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

As we walk around, we notice our minders are filming our visit.

ZAHRA YOUNESI:

[Speaking Farsi] As you can see, there’s nothing hidden here. Everything is out in the open. All the activity that occurs here is easy to monitor. There was nothing [of concern] here.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Do you have any theory as to why Israel would target this place?

ZAHRA YOUNESI:

[Speaking Farsi] I honestly don’t know.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

No idea?

ZAHRA YOUNESI:

No idea.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Days after the strike here, Karaj’s centrifuge production facility was also hit. We ask if we can go see it.

Is it possible we can go to Karaj?

GOVERNMENT MINDER:

What do you want from Karaj?

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

It’s where they say they were manufacturing the centrifuges, in Karaj.

GOVERNMENT MINDER:

No, in Karaj is a military base. They don’t let you go.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

It’s not possible?

GOVERNMENT MINDER:

It needs higher coordination before.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

We continue north to the town where the scientist, Mohammad Reza Seddighi Saber, found refuge in a relative’s home.

He’d been sanctioned by the U.S. in May 2025, accused of working on projects related to the development of nuclear explosive devices.

On the last day of the war, an airstrike leveled the home with him and his relatives inside.

I’m standing literally overlooking the site right now. So, looks like a larger weapon than was used in those strikes on June 13. And it was a long drive to get here. It was around 6 hours from the capital. This is a much smaller, kind of sleepy town almost.

The arrival of local police, as well as men we’re told are intelligence officers, is keeping residents far from our cameras. But the images we’re sending back give the Post and Bellingcat a new window into what happened here.

NILO TABRIZY:

So we were able to confirm this location because the Frontline team visited on the ground and they sent us the coordinates. This is a part of Iran that’s not imaged quite often. This is in Gilan province. This right here where I’m circling my cursor, this is the site that was struck. And then the most recent post-strike imagery was not until August 31, so a couple months afterwards. And this empty lot is where the residences once stood

And so the working theory from a few different experts is that perhaps two different 2,000-pound-equivalent munitions landed in this crater, and then perhaps one last one here. So we were able to measure the crater size. I believe it was between 14 to 16 meters and 7 meters.

TREVOR BALL:

When Saber was actually killed, that was at the end of the war. So it’s possible they used a different munition. Maybe they felt more comfortable with Iranian air defense being degraded. Or maybe it was just because he was further away from Tehran at the time that he was actually killed successfully.

ERIC RICH:

Right, so you guys have spent some time looking at these images, the images from Iran, done some forensic analysis. What is your sense of a takeaway? What have we learned from it?

NILO TABRIZY:

I think it’s helpful to go back to the first wave of—or previous waves of nuclear scientist assassinations in Iran and see how this is completely different. In the first wave of assassinations in the early 2000s, you had Mossad agents driving up on motorbikes, putting magnetic bombs on car windows. And they did these targeted strikes against a few scientists.

ERIC RICH:

And here we see an air campaign, coordinated, multiple scientists. I mean, this feels both different in tactics and also in goal. I think you’re looking at strategic degradation across the program instead of disruption at the level of an individual scientist.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Not far from the site is the mosque where Mohammed Reza Seddighi Saber and his relatives are buried.

Inside, our minders introduce us to someone who says he knew him.

EBRAHIM FALLAH TABASOMCHEHREH:

[Speaking Farsi] He was our next-door neighbor from childhood, and we were in the same neighborhood.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

It seems like he had a high position, that he was closely involved in the program. Can you understand why he was targeted?

EBRAHIM FALLAH TABASOMCHEHREH:

[Speaking Farsi] Obviously the U.S. was worried that he might be useful for the country’s defense industry and may be able to make Iran powerful. That’s why they put him on the sanctions list.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

What impact do you think it will have, the fact that they were able to kill Mohammed Reza? How is that going to affect the nuclear program?

EBRAHIM FALLAH TABASOMCHEHREH:

[Speaking Farsi] Someone who enters this profession, the field of nuclear work, it means he’s laid down his life and is willing to sacrifice his life for the government. This is what a nuclear scientist looks like in our country.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

We want to find out what Iranian officials have to say about these scientists Israel and the U.S. have said were critical to the nuclear program. The head of Iran’s nuclear agency, the AEOI, agrees to meet me. Security guards don’t allow us to film until we’re deep inside his heavily guarded headquarters.

Mohammad Eslami oversees all the country’s nuclear sites.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

How much has the killing of these scientists set back the nuclear program?

MOHAMMAD ESLAMI, Head, Atomic Energy Org. of Iran:

[Speaking Farsi] Nothing. Zero impact. They were university lecturers.

They worked in labs and classrooms, not for our organization. Nothing will change.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

The U.S. says the goal of the nuclear program is to produce a nuclear weapon. What’s your response?

MOHAMMAD ESLAMI:

[Speaking Farsi] It’s a lie. They clearly lie. Which country’s plans are discussed except Iran’s? Does anyone ever question Israel’s stockpile of nuclear weapons?

Just as with other countries pursuing these technologies, the goal of Iran’s nuclear program is to improve the quality of life of our people, both in the energy sector and the non-energy sector.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

We leave Tehran and travel south, through the mountainous landscape that’s home to three nuclear sites that the U.S. and Israel say are the heart of Iran’s secret weapons program, where its stockpile of near weapons-grade uranium is believed to be produced and stored.

Israel bombed the sites, and on the 10th day of the 12-day campaign, America joined the attack.

June 21, 2025

DONALD TRUMP:

A short time ago, the U.S. military carried out massive precision strikes on the three key nuclear facilities: Fordow, Natanz and Isfahan.

GEN. DAN CAINE, Chmn., Joint Chiefs of Staff:

In total, U.S. forces employed approximately 75 precision-guided weapons during this operation.

DONALD TRUMP:

Iran’s key nuclear enrichment facilities have been completely and totally obliterated.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

As we approach Isfahan, the city closest to one of the key nuclear facilities, our minders want us to film the site of another Israeli strike. They tell us that two cars with civilians were hit by an Israeli missile, and they’ve called someone they say is a witness to meet us.

ESMAIL MALEKEH:

[Speaking Farsi] I took this video when I arrived. When I arrived, the bodies had been flung forward from over there, and the car in the other direction. One body had fallen over here. That was the body of the pregnant woman. And there was another body further ahead over there. They didn’t have arms or legs.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Did you see the strike?

ESMAIL MALEKEH:

[Speaking Farsi] Yes, I was here and saw a jet fly by, followed by an explosion on that road.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Is there a CCTV camera here?

ESMAIL MALEKEH:

[Speaking Farsi] Yes, the university security had cameras here. They recorded it.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

The Israeli military told us they had no knowledge of a strike at this location.

Isfahan, Iran

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

We eventually arrive in Isfahan, 12 weeks since U.S. cruise missiles slammed into the nuclear facility on its outskirts where we’re hoping to film.

The city looks different from trips we’d taken here before, with fewer women wearing the hijab, a sign of opposition that’s been building for years against theocratic rule. As we wait for permission, our minders tell us we can ask people about the bombing. But on that question, no one wants to speak.

Excuse me, do you guys speak English, by any chance?

FEMALE PASSERBY:

Yeah.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Can we interview you?

FEMALE PASSERBY:

Umm—

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

On-camera? Is it possible?

FEMALE PASSERBY:

Umm—No.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

OK.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Can we talk to you, on-camera?

FEMALE SHOPPER:

No problem, what do you ask me?

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

About the 12-day war.

FEMALE SHOPPER:

No.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

[Laughs] OK. All right, thanks.

In the end, a message comes from Tehran that we’re not going to be allowed to film the damage at the center. They claim it’s not safe.

This is as close as they’ll take us. The bombed facility is just behind this ridge.

Do you think we could get a shot from that place?

GOVERNMENT MINDER:

It’s a station for cable cars.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

For the nuclear center, could we drive close to it? Even if we don’t stop and get out?

GOVERNMENT MINDER:

Even from the car, you need permission.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Even from the car?

GOVERNMENT MINDER:

Yes.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

But away from Isfahan, my colleagues back in Washington have been piecing together what happened there and at the other nuclear sites.

Isfahan is Iran’s largest nuclear complex. The U.S. says it launched more than two dozen precision-guided Tomahawks at the site. Satellite imagery obtained by the Post‘s visual forensics team shows damage to the main uranium conversion facility.

NILO TABRIZY:

This piece of damage is from Israeli strikes previously, and then this is when the U.S. hit the Isfahan center here, and our sources told us that this damage means that it was knocked almost completely out of operation.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Isfahan is also reported to have held much of Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium. What happened to that material is unclear.

The U.S. says Natanz was struck by two bunker-busting bombs known as Massive Ordnance Penetrators, or MOPs. Satellite imagery shows visible penetration points that align with underground centrifuge buildings.

Israel had also struck the electrical infrastructure here, crippling the site before the U.S. bombs did their damage.

JARRETT LEY:

And that electricity is so key because the centrifuges are spinning at such a high rate that if the electricity is cut the spinning will stop, and that can compromise the structural integrity of these very delicate machines such that they will spin out and destroy themselves.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Fordow took the heaviest hit. The U.S. focused their most powerful munitions on what it considers Iran’s most important enrichment site, buried deep inside this mountain range. The U.S. says B-2 bombers dropped 12 MOPs, most of them through two ventilation shafts. Satellite imagery before and after the strike show two ventilation openings that appear to confirm this, but not the extent of the damage.

The team has also been able to gather information on what may have happened once the bombs penetrated underground at Fordow. Using floor plans released after a 2018 raid by Mossad and diagrams exhibited by the Pentagon, the Post built a 3D model of the likely position of the underground complex and its ventilation infrastructure.

It shows the MOPs entering above or near the areas probably used for enrichment activity, but it suggests multiple scenarios about the possible level of damage. A source with knowledge of the design said the center shafts of each structure zigzag on their way to the centrifuge halls below, which would mean the MOPs could have hit additional rock.

If the MOPs managed to penetrate to the halls, they in all likelihood would have destroyed the centrifuges and related infrastructure.

JARRETT LEY:

The MOPs still could have undermined the centrifuges even without penetrating the interior. If they had penetrated the halls, it would have been catastrophic. If it were to hit from above the facility, but not inside the facility, the force of that explosion would still move through the rock and rattle the facility in a way that could cause the function of the centrifuges to be undermined.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Regardless of the damage, it’s still unclear how much of Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium was destroyed, whether it’s buried under rubble in these bombed facilities, or whether at least some is in another location.

In the meantime, our colleagues at the Post have also begun to detect new activity at another underground facility that was not bombed.

NILO TABRIZY:

There’s something I wanted to ask you, and you’re in a pretty sensitive reporting environment, so I can’t explicitly say the names, but there is a site of interest that we have that was not hit by U.S. strikes, but it’s an important site. So I just want to flag there has been some increased activity that we’ve seen on satellite imagery.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

The activity the Post has detected is at a site built inside a mountain called Kuh e Kolang Gaz La, or “Pickaxe Mountain.”

On our journey back from Isfahan, the road passes close to Pickaxe Mountain. We find an excuse to stop and take pictures. The complex is somewhere in this range, believed to be buried deeper than any of the facilities that were bombed.

NILO TABRIZY:

Seb took some photos from here of Pickaxe.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Our photos add to a picture the team is building on Pickaxe from satellite imagery.

JARRETT LEY:

You really get a sense of the topography there, which you kind of lose in the satellite.

Part of the security infrastructure that is expected at a site like this would be building perimeter walls and security features that have controls of what comes in and what comes out.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Iran has said the purpose of Pickaxe Mountain is to house a production plant for assembling centrifuges.

JARRETT LEY:

The ability for the regime to reconstruct centrifuges is going to be important in their ability to bounce back, which puts more eyes on Pickaxe. And if indeed there is centrifuge construction taking place there, what that means is that they would be able to come back relatively quickly.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Analysts also suspect that Pickaxe’s dimensions and estimated depth could be used for uranium enrichment, or for storing near weapons-grade uranium.

Using satellite imagery, the Post has been able to show the site is now being fortified and expanded.

JARRETT LEY:

Here this summer, on the right-hand side, you can see the status of the security wall underway. You can see them making their way through the rock. Now compare that here, on the left, now this fall, where you can see that security perimeter becoming closer to completion.

ERIC RICH:

I think what’s so interesting about this site is it gets at this question of what’s next, and we’re seeing evidence, it sounds like, of a continuation of the program at this site.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

The satellite imagery shows that two tunnel entrances have been covered with dirt and rock, which experts say hardens them against possible airstrikes. And piles of excavated material, or “spoil,” next to the entrances have increased in size, indicating continued tunneling activity.

Recent satellite imagery also shows the presence of heavy equipment and construction vehicles.

NILO TABRIZY [on phone]:

Hey, Seb. I just want to touch base on Pickaxe with you. The purpose of Pickaxe is unclear. International inspectors have never gained access to it. So any information you can find out would be really helpful.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Hey, thanks for that. We are now back in Tehran. Hopefully we’re going to get to speak to a senior official. I’ll take it up with them, and I’ll keep you posted.

Our trip near its end, we finally hear that the senior official we can meet is one of Iran’s most powerful leaders.

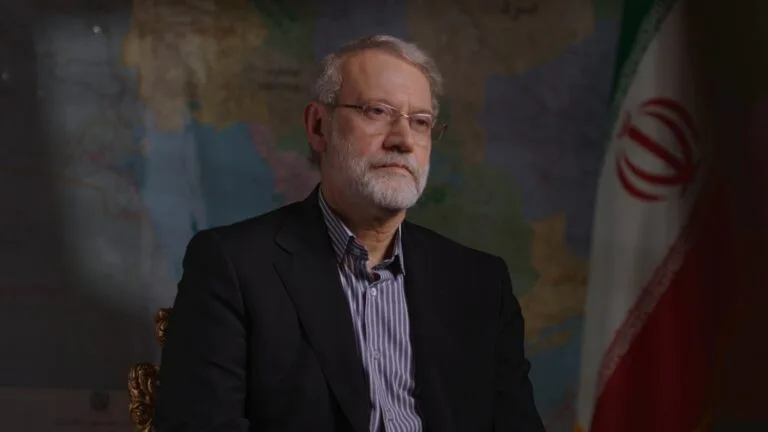

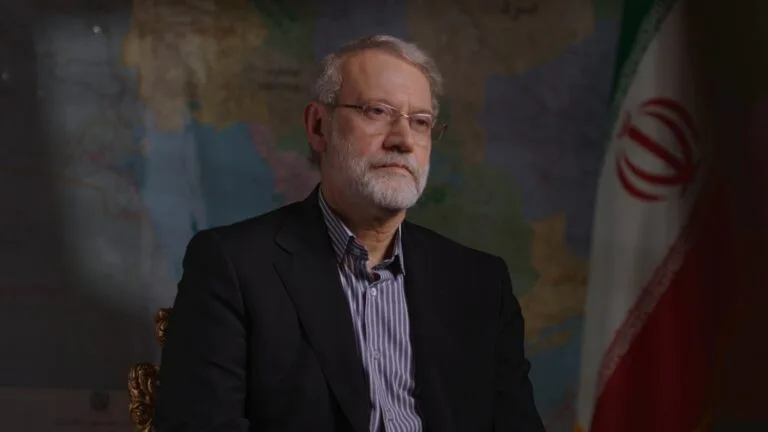

Ali Larijani is in charge of both Iran’s national security and decisions around its nuclear policy. He reports directly to Ayatollah Khamenei. This is his first interview since the 12-day war.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Can you say definitively here, now, after the strikes, that Iran has no intention of developing a nuclear weapon?

ALI LARIJANI:

[Speaking Farsi] We never had those intentions, as we have repeatedly stated.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

And in the future, is that out of the question?

ALI LARIJANI:

[Speaking Farsi] It is not the policy of the Islamic Republic to pursue nuclear weapons.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

With the sites that were hit by American strikes, President Trump has said that the enrichment facilities targeted were “completely and totally obliterated.” Is he right?

ALI LARIJANI:

[Speaking Farsi] You need to ask him. He announced that his forces were brave and powerful. That they bombed us and were successful. You shouldn’t discount his words.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

There’s a site south of Natanz where international observers have seen new reinforcements of the entrance; there’s been some activity noticed there. It’s known as Pickaxe Mountain. Is there any new activity that these strikes have created? Is there anything you can tell us about that site?

ALI LARIJANI:

[Speaking Farsi] No, nothing. We haven’t abandoned any of those locations. But in the future they could possibly continue to run as they currently do or be shut down.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

What’s your assessment of the extent to which these sites have been damaged and how much this has set back Iran’s nuclear program?

ALI LARIJANI:

[Speaking Farsi] I don’t have any specific information to share. But in my opinion, Iran’s nuclear program can never be destroyed. Because, once you have discovered a technology, they can’t take the discovery away. It’s as if you are the inventor of some machine, and the machine is stolen from you. You have the knowledge needed to make another one.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Our minders take us to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps missile museum, where Iran’s latest military hardware is on display. It’s believed some of these ballistic missiles could be capable of carrying nuclear warheads.

Despite the 12-day war, Iran and its leaders continue to shroud its nuclear program in secrecy and mystery.

It’s time to leave Iran and seek answers elsewhere. We travel to Vienna, home to the IAEA, the world’s governing nuclear watchdog.

Rafael Grossi is the head of the agency. His inspectors were on the ground in Iran prior to the bombing but haven’t been allowed to return to the sites hit by the U.S. and Israel.

You have the ability to assess damage in a unique way that others don’t. What was your initial assessment after the strikes on the key facilities, Natanz, Fordow and Isfahan?

RAFAEL GROSSI, Director General, IAEA:

Obviously without having physical access to a place, any evaluation is partial. It’s not complete. But the difference between our assessment and the assessment of anybody else is that we knew exactly what was inside.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Can you give us an overall picture of what that determination was?

RAFAEL GROSSI:

The determination was, and still is, that the damage was very substantial. Very substantial.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

While President Trump has insisted that Iran was nearing a bomb, Grossi says he hasn’t seen evidence of an active weapons program. But he’s concerned about the amount of enriched uranium Iran was stockpiling.

How far do you think Iran is today from developing a nuclear weapon?

RAFAEL GROSSI:

I think here we have to be very careful what we say. All the access and inspections that we were carrying out allowed us to determine that there is no credible information that would lead us to believe that they were developing a nuclear weapon. So this I think has to be said very clearly. As well as the rest: a number of, I mean a huge amount of near weapon-grade enrichment, and of course these technological capabilities that were there, which were a source of legitimate concern by the international community.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

Do you think that there is a risk from these strikes that it pushes Iran’s nuclear program further underground?

RAFAEL GROSSI:

If time passes and inspections do not resume, well, then there will be doubts. And I mean, I’m not saying that there will be an immediate consequence, but certainly the situation will become a source of a greater concern in terms of nonproliferation or the potential activities leading to a nuclear weapon.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

At the Imamzadeh Saleh mosque in Tehran, nuclear scientists and military commanders killed in June are buried and venerated as heroes.

The country is at a crossroads over its nuclear future and how its adversaries will respond.

So how are people feeling now? Are you expecting or worried about more conflict that’s coming?

FEMALE SPEAKER:

Yeah, of course, because they say it’s not ending. And every day it’s passing that Trump say one thing, Netanyahu say another. And every night that we want to go to sleep, we don’t know if tomorrow we wake up or not.

BENJAMIN NETANYAHU:

We must not allow Iran to rebuild its military nuclear capacities. Iran’s stockpiles of enriched uranium … these stockpiles must be eliminated.

DONALD TRUMP:

My position is very simple: The world’s number one sponsor of terror can never be allowed to possess the most dangerous weapon.

SEBASTIAN WALKER:

What’s your message to the Trump administration if there are more attacks? What would be the consequences of that?

ALI LARIJANI:

[Speaking Farsi] I don’t have a message for the Trump administration. I would only say that they should be mindful of their words and the insulting way they speak to Iranians. When he says, “Iran must surrender,” it is clear he’s not familiar with the Iranian people. There is no possibility or chance that we will surrender.

WRITTEN, PRODUCED & DIRECTED BY Adam Desiderio & Sebastian Walker

CORRESPONDENT Sebastian Walker

REPORTED BY Nilo Tabrizy Jarrett Ley Souad Mekhennet

EDITOR Andrew Pattison, A.C.E.

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY Javier Manzano

SENIOR PRODUCERS Dan Edge Eamonn Matthews Frank Koughan

RESEARCHERS Skye Lucas Kristina Abovyan

ADDITIONAL CAMERA Ray Whitehouse Adam Desiderio David Blumenfeld

HEAD OF PRODUCTION Belinda Morrison

ARCHIVE PRODUCER Izze Gibson

ARCHIVE RESEARCHER Kelsey Belrose

GRAPHICS Jennifer Smart Jarrett Ley

ORIGINAL MUSIC Louis Dodd

ONLINE EDITOR / COLORIST Jim Ferguson

SOUND MIX Jim Sullivan

ADDITIONAL EDITING Simon Ardizzone

LOCAL PRODUCER, ISRAEL Oren Rosenfeld

ADDITIONAL TRANSLATION Kian Ahmadi

ARCHIVAL MATERIAL AFP via Getty Images Alireza Norouzi Associated Press CNN Getty Images Iraj Rasooli Masoud Lak Pond5 Siamak Darvish Vantor

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL Al Jazeera CBS News DEFA Press Fox News Gilan Press Iran Observer ISNA Mehr News Agency Tehran News Tehran Times United Nations

IRAN PRODUCTION SERVICES Ivan Sahar

FOR THE WASHINGTON POST

VISUAL FORENSICS REPORTER Nilo Tabrizy

VISUAL FORENSICS REPORTER Jarrett Ley

INTERNATIONAL SECURITY REPORTER Souad Mekhennet

NATIONAL SECURITY REPORTER Warren Strobel

DEPUTY INVESTIGATIONS EDITOR Eric Rich

VISUAL FORENSICS EDITOR Nadine Ajaka

NATIONAL SECURITY EDITOR Ben Pauker

INTERNATIONAL EDITOR Peter Finn

INVESTIGATIONS EDITOR David Fallis

MANAGING EDITOR Kimi Yoshino

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Matt Murray

FOR BELLINGCAT

INVESTIGATOR Trevor Ball

INVESTIGATOR Sebastian Vandermeersch

HEAD OF RESEARCH Carlos Gonzales

LEAD EDITOR Eoghan Macguire

FOR EVIDENT MEDIA

SENIOR ANIMATOR Jennifer Smart

ASSISTANT PRODUCER Ivette Galvez

EXECUTIVE CREATIVE DIRECTOR Kevin Clancy

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Zach Toombs

IRAN PRODUCTION SERVICES Ivan Sahar

In association with ARTE France

Unité Société et Culture Fabrice Puchault Anne Grolleron

Commissioning editor Alexandre Marionneau

ORIGINAL PRODUCTION FUNDING PROVIDED BY Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Ford Foundation, Abrams Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Park Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, FRONTLINE Trust with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler through the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, additional support from Koo & Patricia Yuen and from Laura DeBonis and Scott Nathan.

FOR FRONTLINE

POST PRODUCTION MANAGER Tim Meagher

SENIOR EDITOR Barry Clegg

EDITOR Brenna Verre

EDITORS Christine Giordano Joey Mullin

ASSISTANT EDITORS Hinako Barnes Thomas Crosby Julia McCarthy

FOR GBH OUTPOST

SENIOR POST PRODUCTION MANAGER Beth Godlin Lillis

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY Tim Mangini

INTERNS Tom Brown Nicholas Doyle

SERIES MUSIC Mason Daring Martin Brody

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT Ellen O’Neill

DIRECTOR OF IMPACT AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS Erika Howard

SENIOR DIGITAL WRITER Patrice Taddonio

PUBLICITY & AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT COORDINATOR Julia Heffernan

ASSISTANT DIGITAL EDITOR Ambika Kandasamy

ASSOCIATE DIGITAL EDITOR Mackenzie Wright

DIGITAL PRODUCER / EDITOR Tessa Maguire

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS Anne Husted Blatt

ARCHIVES & RIGHTS MANAGER John Campopiano

SENIOR BUSINESS ASSOCIATE Sean Gigliotti

FOR GBH LEGAL Eric Brass Suzy Carrington Jay Fialkov

SENIOR CONTRACTS MANAGER Gianna DeGiulio

SENIOR BUSINESS MANAGER Sue Tufts

SENIOR DIRECTOR, BUSINESS & OPERATIONS Mary Sullivan

SENIOR DEVELOPER Anthony DeLorenzo

LEAD, DIGITAL DESIGN & INTERACTIVE Dan Nolan

FRONTLINE/COLUMBIA JOURNALISM SCHOOL FELLOWSHIP TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW Jala Everett

FRONTLINE/NEWMARK JOURNALISM SCHOOL AT CUNY FELLOWSHIP TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW Sunny Nagpaul

FRONTLINE/MISSOURI SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM FELLOWSHIP MURRAY JOURNALISM FELLOW Skye Lucas

PBS CREATIVE VOICES FELLOWSHIP DIGITAL PRODUCER Tasnia Choudhury

ARCHIVAL PRODUCER Coral C. Salomón Bartolomei

SENIOR DIGITAL PRODUCER / EDITOR Miles Alvord

SENIOR DOCUMENTARY EDITOR & PRODUCER Michelle Mizner

DIGITAL EDITOR Priyanka Boghani

STORY EDITOR & COORDINATING PRODUCER Katherine Griwert

POST COORDINATING PRODUCER Robin Parmelee

SENIOR EDITOR AT LARGE Louis Wiley Jr.

FOUNDER David Fanning

SPECIAL COUNSEL Dale Cohen

SENIOR PRODUCERS Dan Edge Frank Koughan

SENIOR EDITOR & DIRECTOR, LOCAL JOURNALISM Erin Texeira

SENIOR EDITOR, INVESTIGATIONS Lauren Ezell Kinlaw

MANAGING EDITOR Andrew Metz

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Raney Aronson-Rath

A FRONTLINE Production with Mongoose Pictures in association with The Washington Post, Evident Media and Bellingcat

© 2025 WGBH Educational Foundation All Rights Reserved

FRONTLINE is a production of GBH, which is solely responsible for its content.

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.