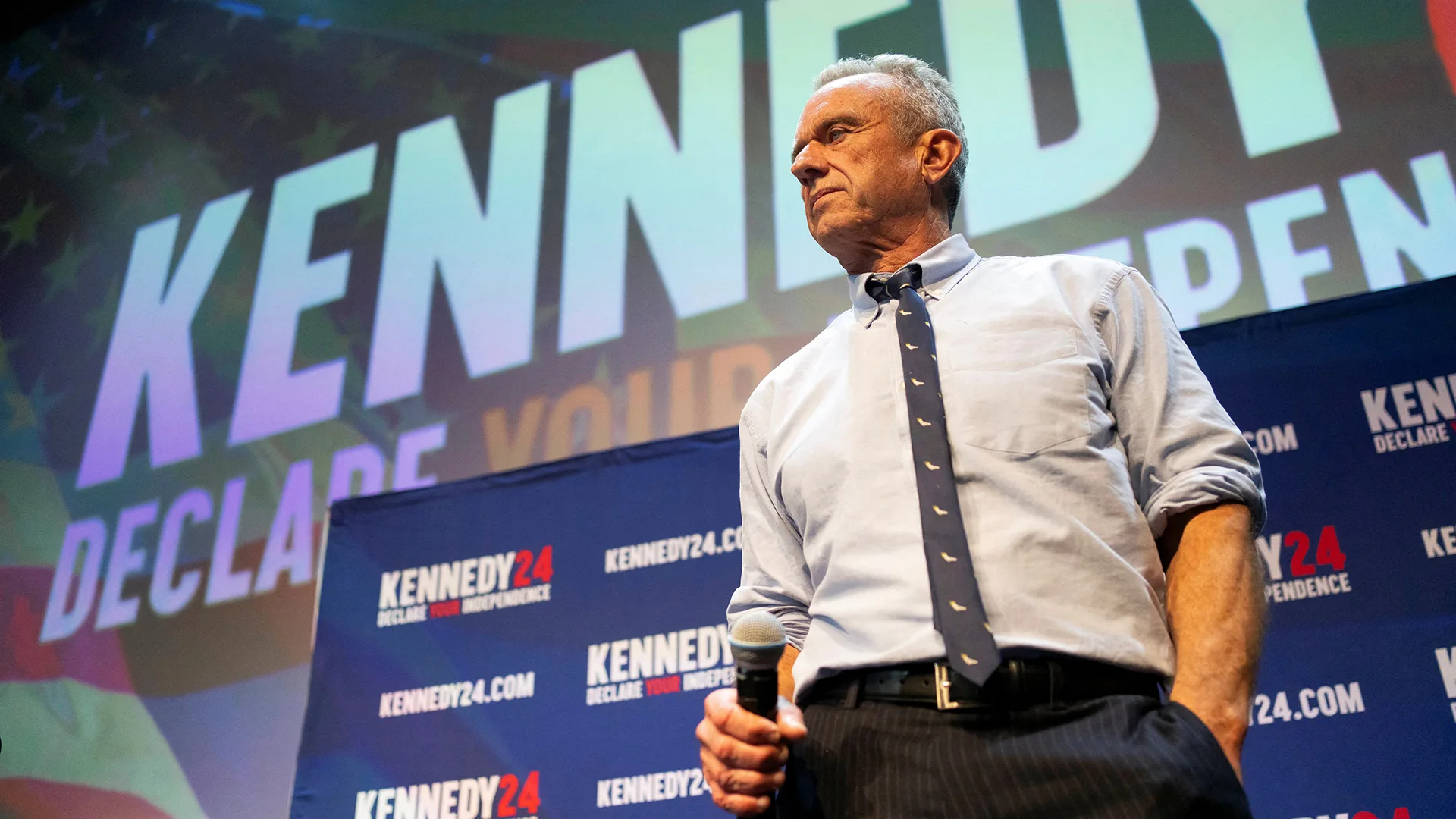

Syria’s Detainee Files

June 10, 2025

1h 24m

FRONTLINE investigates the Assad regime’s arrest, torture and execution of detainees during the Syrian war

Syria’s Detainee Files

June 10, 2025

1h 24m

Share

FRONTLINE investigates the Assad regime’s arrest, torture and execution of detainees during the Syrian war. Former prisoners, guards, soldiers and intelligence officials shed new light on atrocities carried out during Bashar al-Assad’s reign.

Directed by

Produced by

Transcript

Credits

Journalistic Standards

Support provided by:

Learn More

Most Watched

The FRONTLINE Newsletter

‘What They Left Behind’: A Look at the Human Toll of the Syrian War

‘I’d Scream Louder’: After Assad’s Fall, Brothers Return to Saydnaya Prison Where They Were Tortured

Syria’s War Began 14 Years Ago. Explore FRONTLINE’s Reporting on Its Origins and Consequences

Related Stories

Syria’s War Began 14 Years Ago. Explore FRONTLINE’s Reporting on Its Origins and Consequences

‘I’d Scream Louder’: After Assad’s Fall, Brothers Return to Saydnaya Prison Where They Were Tortured

‘What They Left Behind’: A Look at the Human Toll of the Syrian War

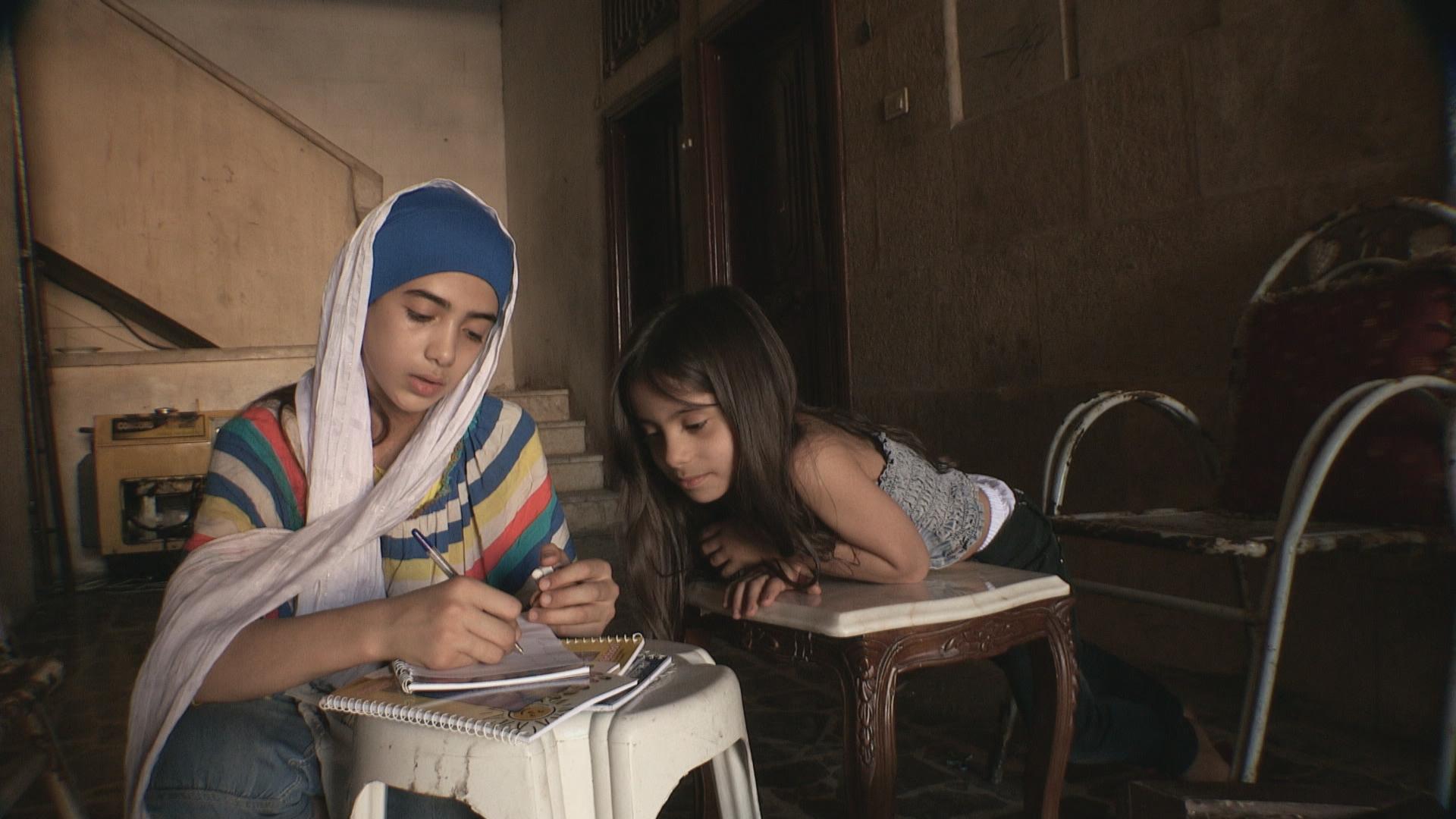

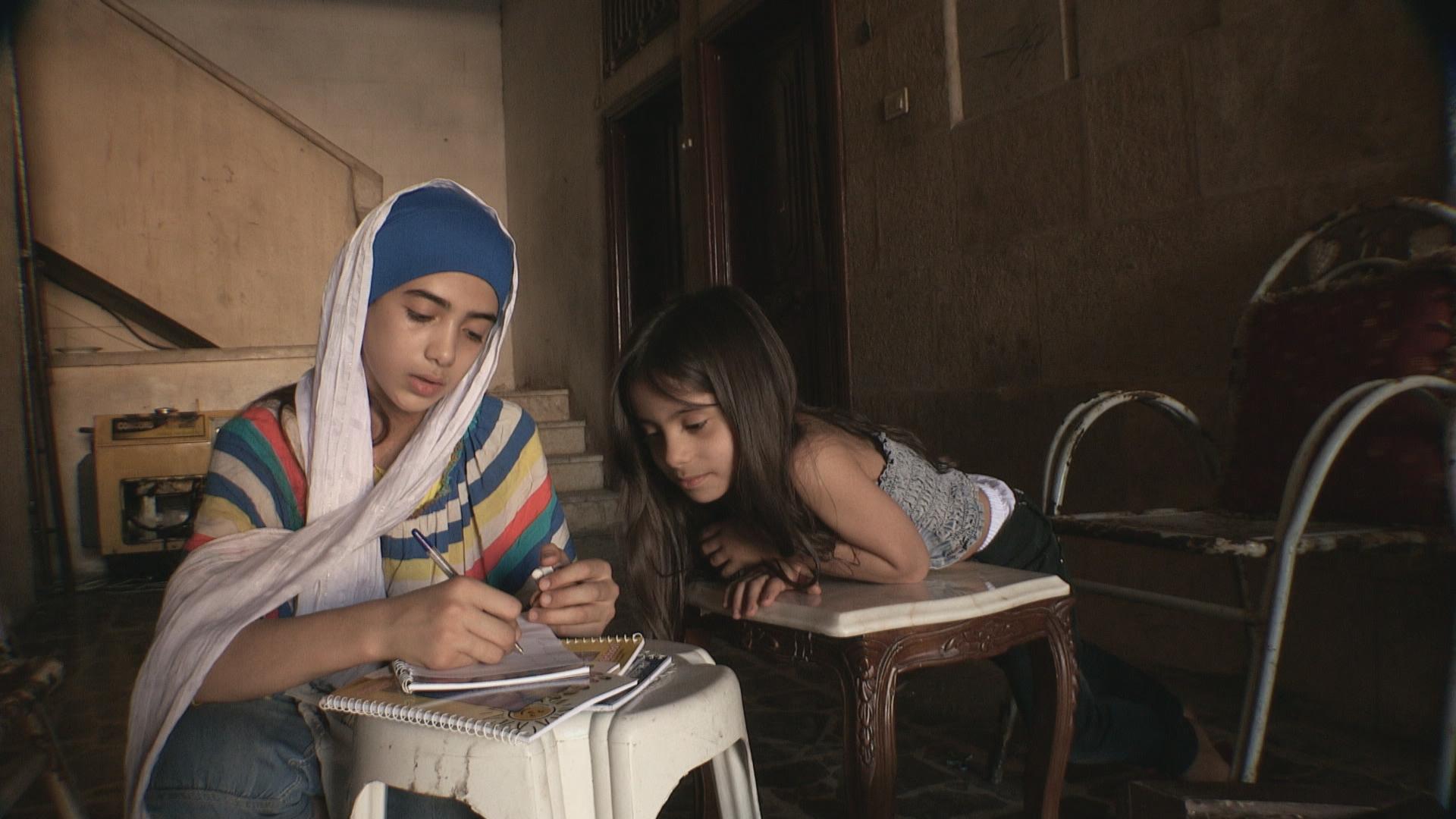

Children of Syria

For Sama

Related Stories

Syria’s War Began 14 Years Ago. Explore FRONTLINE’s Reporting on Its Origins and Consequences

‘I’d Scream Louder’: After Assad’s Fall, Brothers Return to Saydnaya Prison Where They Were Tortured

‘What They Left Behind’: A Look at the Human Toll of the Syrian War

Children of Syria

For Sama

This program contains graphic imagery and descriptions of violence. Viewer discretion is advised.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] This is my solitary cell. Number 21.

During the Syrian war, more than 1 million people were detained by the regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

More than 100,000 are still missing.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Here is where they would suspend people, on this door. Like this. They’d hang people right here with these chains. They’d bring a cable and they’d suspend us like this. This is the “ghost method.” You’d be handcuffed here, and you’d go down like this. They’d pull us up and we’d be on our toes. You’d last 30 minutes and then you’d pass out. It was impossible to endure.

This is what used to happen.

“HUSSAM,” Military Police:

[Speaking Arabic] When the prisoners heard my name, they would tremble. I showed them no mercy, at all.

Over the past two years, FRONTLINE has been tracking down former insiders from the Assad regime.

Some had already defected and were living in hiding.

Others were loyal until the end.

MAJOR “RIYAD,” Syrian Air Force:

[Speaking Arabic] Every head of branch or intelligence unit wants to prove their worth to Bashar al-Assad.

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] It was a police state. People were afraid to speak up. The walls have ears.

This is the story of a brutal system of detention, torture and mass killing.

Told by those who survived it.

And those who were part of it.

SARA OBEIDAT, Producer:

[Speaking Arabic] Why couldn’t you try to stop the torture?

COLONEL “ZAIN,” Air Force Intelligence:

[Speaking Arabic] [Laughs] You’re talking like it was a country that respected humans.

SERGEANT “OMAR,” Air Force Intelligence:

[Speaking Arabic] These are people who haven’t seen the light of day for years.

OFFICER “KAMAL,” Army nurse:

[Speaking Arabic] Tens of thousands of detainees were buried, and no one knows anything about them.

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] It is true that I tortured, it is true. But today I am exposing the prisons to the outside world.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Let’s get out of here. I’ve had enough.

Damascus

December 2024

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I was detained in 2011. I was then 27 years old. And when I was released I was 36 years old. I lost almost 10 years of my life because of someone’s decision. “Simply erase 10 years of his life, from the smallest moments to the most important ones.”

SARA OBEIDAT:

Four days after the fall of Bashar al-Assad, we went with Shadi Haroun and his younger brother Hadi to Saydnaya prison, where they were once detained and tortured.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Families of the disappeared were making the same journey, searching for their loved ones.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] This is the entrance of Saydnaya prison, the human slaughterhouse.

SARA OBEIDAT:

After almost a decade as prisoners, the brothers are now working with a human rights organization to gather evidence of crimes committed by the Assad regime.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] This is the main entrance. You can see the people are still coming here, looking for the prisoners. This is the administrative building where the files were kept. All these files on the ground. These are the names people are looking for.

Search every section. This is a register. All burned. One of the papers fell out. These are the names of prisoners transferred to the hospital. Dated April 16, 2017. Corpse, so this one was deceased. His prison number in his file is 16786.

MALE SPEAKER [shouting]:

[Speaking Arabic] You took them away from us. May God take his revenge on you. May God take his revenge on you, Bashar al-Assad. Listen up, people.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Excuse me.

MALE SPEAKER [shouting]:

[Speaking Arabic] We saw what happened in Syria. We still don’t know where our loved ones were imprisoned. It’s been three, four days, and we don’t know. Four days we’ve been waiting. May God take revenge on you, Bashar.

MALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] Have you seen Mohamed Abdallah al-Salman?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] No, I have not. We’re put into one cell. We don’t get to roam around.

MALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] My brother, here, was a soldier.

FEMALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] I’m looking for two brothers, Omar and Saleh.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] No.

MALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] Have you come across a man named Ali Edwani?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] No, I’m sorry.

MALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] Did you meet a prisoner from Daraya?

MALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] Did you know an inmate with the last name Maser?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] No.

MALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] Did you come across Bassam al-Hourani?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I was not a smoker. I got through university without ever smoking a cigarette, because life was so sweet back then. [Laughs]

Spring 2011

PROTESTERS:

[Chanting in Arabic] Get out, Bashar!

MALE NEWSREADER:

The demand for political change that started in Tunisia has now reached Syria.

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

—which has scene unprecedented challenges to the 10-year rule to President al-Assad.

MALE NEWSREADER:

The antigovernment demonstrations are getting bigger and they’re spreading.

MALE NEWSREADER:

Some of the demonstrators have been openly calling for revolution.

SARA OBEIDAT:

When Syria’s uprising began, Shadi and his brother joined the protests, and within a month, they were organizing them in their home town.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I was happy. I felt that I could finally speak up. That this person is not an untouchable god.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] For me, it was an amazing feeling. I’m not saying that Syria was already liberated, but we were taking the first step.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] On April 22, there was a call for the downfall of the regime. The idea was that we needed to take over one of the squares in the city. We thought we’d stay in the square for three or four days, like what happened in Egypt. That’s what we imagined. And then someone would announce, “Bashar is gone, you’re free to go.” [Laughs]

April 22, 2011

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] It was me, Shadi and a large group of friends at the front [of the protest]. Halfway into the march we said, “Let’s go to Zablatani and march to Damascus.”

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I had binoculars so I tried to look ahead. I spotted a sniper on top of the tower.

MALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] This is the regime’s sniper on top of the tower. But we are not afraid.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Within seconds there was relentless gunfire. People started screaming, “A martyr, we have a martyr. Save him.”

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] We were caught in the middle and we no longer knew where to run.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I couldn’t find Shadi. I called, “Shadi,” but he didn’t answer.

MALE SPEAKER:

[Speaking Arabic] Security forces are arresting people who are trying to help the injured.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] A car stopped. Two armed men got out and pointed their weapons at us.

SARA OBEIDAT:

On that day, Assad’s security forces killed more than 100 protesters and arrested thousands across the country. Shadi was one of them.

He says he was taken to what looked like a normal house in a residential neighborhood in Damascus. But inside was an interrogation center run by Syrian Intelligence.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I’ll never forget what happened next. The soldier told me to open my mouth. He put his gun inside. He said, “You are going to get tortured, tortured, tortured to death. So why don’t I just make it easier for you?”

COLONEL “ZAIN,” Air Force Intelligence:

[Speaking Arabic] As security officers, we had the right to kill as we pleased. And we wouldn’t be held accountable.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Col. “Zain” was a high-ranking Air Force Intelligence officer when the uprising began. He eventually defected in 2014. He’s one of 40 former regime officials of various ranks we tracked down across a dozen countries. We verified their identities by examining military IDs and other documents, and cross-referencing their accounts with those of other insiders and former prisoners.

Many of them spoke to us before the fall of Assad and feared reprisals from both sides. Some have given testimony to human rights groups or courts investigating war crimes.

We agreed to conceal their identities and change their names given the value of their firsthand accounts about the abuses carried out by the Assad regime.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] The Air Force Intelligence had branches and outposts all over Syria. Its mission, like any other agency, was to protect the ruling regime. Especially if there were any signs of dissent within the army or the air force. There was a lot of ambiguity in how we operated. You have unlimited authority. Go anywhere you want. Do whatever you please.

This means a commander of a brigade had the power to build prisons. He could establish checkpoints, arrest people with impunity. The most important thing is to gather intelligence about threats to the regime.

SARA OBEIDAT:

For decades, Syria’s intelligence agencies were seen as pillars that upheld the state. The country had four of them. The most powerful and prestigious was created by Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez—Air Force Intelligence.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] Honestly, this was the dream job. Officers could be tempted with benefits like a house, a car, an office and things like that. The power, the authority. So kill, do whatever, and we’ll have your back. But thankfully I didn’t get involved in that.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Did they give you those things?

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] Of course, they gave me a car on day one. It was brand new. [Laughs] And they gave me an office and everything.

SERGEANT “OMAR,” Air Force Intelligence:

[Speaking Arabic] I volunteered so I could carry a gun. It appealed to me, that’s it.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Sgt. “Omar” was another Air Force Intelligence officer. He defected about a year after the uprising began and ultimately fought against the regime.

SERGEANT “OMAR”:

[Speaking Arabic] No one can say anything to an intelligence officer. They were the ultimate authority in Syria. If you write someone up, they would disappear for six months and nobody would ask why. All it takes is a report.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] We knew they had him. He was detained, but where? Was he dead or alive? We had no idea, and no one told us anything.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Shadi’s family paid a middleman to try and find out where he was detained. Regime officials were known to take bribes for this kind of information

[Speaking Arabic] Have you ever seen officers take bribes from families of detainees?

MAJOR “RIYAD,” Syrian Air Force:

[Speaking Arabic] Have I seen officers?

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] I mean, have you seen people taking bribes?

MAJOR “RIYAD”:

[Speaking Arabic] All the officers. I’ll answer that after I smoke a cigarette.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Maj. “Riyad” was an officer in the Syrian Air Force who says he was assigned to Air Force Intelligence when the uprising began.

MAJOR “RIYAD”:

[Speaking Arabic] Look, Miss, when it comes to this issue, it’s not just the officers. Not just the officers. It’s an entire network. An entire network of judges, lawyers and officers that exploits families of detainees. It’s all about collecting money and taking advantage of the detainees’ families.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] The middlemen we used to search for Shadi all came back with the same answer, “Don’t look for him.” So I wondered, why? What has he done?

SARA OBEIDAT:

Around two months into the uprising President Assad tried to defuse the protests by meeting with communities across Syria, including Shadi’s neighborhood.

PRESIDENT BASHAR AL-ASSAD:

[Speaking Arabic] My extensive meetings with the local delegations have opened more direct communication channels between me and our people.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Hadi told us he was in a delegation that met President Assad, and he asked for the release of his brother. He says the president agreed and he was sent to see the head of Air Force Intelligence, Maj. Gen. Jamil Hassan.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] He was seated, so he said, “Have a seat.” He raised his glasses and looked at me and said, “I don’t want to release your brother, it’s that simple.” I said, “I’m sorry, Major General. There is an order from Bashar al-Assad to release him.” I said it so confidently. He said, “Sure,” then picked up the phone and dialed a number. “With respect, sir, you ordered the release of Shadi Haroun. But he is a danger to the country. I want to question him myself. Then, with your approval, I’ll decide if he should be released.” He said, “You see, I don’t want to release him.”

I couldn’t understand what he was doing. Was he trying to send me a message that Bashar al-Assad may be the president of this country, but I’m the president of this mini state? As in, “I am the president of the state of Air Force Intelligence.”

SARA OBEIDAT:

It’s December 2024, soon after the fall of Assad. Shadi’s heading to an Air Force Intelligence facility called Mezzeh Investigations Branch.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Get ready.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Let’s get out.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Those are the new and the old branches.

Mezzeh Air Base

Air Force Intelligence

SARA OBEIDAT:

Located on an airbase, this was one of the regime’s most notorious detention sites. Shadi’s looking for information about those who are still missing.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] These are some photos of the detainees, taken when they’re brought into the branch. They’re photographed and given a number. This one’s number is 132.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Why would you assign them numbers?

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] To hide their identities, and hide them from their families. So no one could figure out who that person is.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Although prisoners’ identities were being hidden from the public and other detainees, meticulous records were kept about who was being held and where. The detainees’ files are a trove of potential evidence for Shadi and his organization. But they’re in disarray, and many have been destroyed.

SHADI HAROUN:

This is like, the number of this body is 10002. This is one person, and this is the story of this person. No name.

SARA OBEIDAT:

In May 2011, Shadi was transferred here, to Mezzeh Investigations Branch.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] It was considered the most infamous branch within Air Force Intelligence. It was responsible for cases that posed a serious threat to the regime.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I heard a voice saying, “Bring him in.” He asked, “Are you Shadi Haroun?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Lift the blindfold.” So they lifted the blindfold. I was talking to a brigadier general. Then I read the name, Abdul Salam Mahmoud.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Abdul Salam Mahmoud was the head of the Investigations Unit at Mezzeh. There’s no publicly available photo of him, and his whereabouts are unknown.

The U.S. has charged him with conspiracy to commit war crimes through the cruel and inhuman treatment of detainees, and a French court has convicted him of complicity in crimes against humanity.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] He said, “Shadi, you formed a terrorist group and you’re being financed for it. You’re coordinating people to protest and take up arms against the state.” He said, “It’s better for you to confess, and things will be OK.” I said, “Why should I confess? Do you think I’m an idiot? What terrorist group? All I did was protest. That’s it.”

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] Anyone against the regime is a terrorist. Whoever, protester, civilian, military personnel, they were terrorists.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Then he called the investigator and said to him, “This man, flay him and break his bones. Kill him, do whatever you want, but I need his confession on my desk.”

He told me to lie down. They handcuffed my hands behind my back and then cuffed my feet. Then they joined my hands and feet together. They wrapped me up in a blanket, like being inside a pipe. People started to mess with me for fun. I was sweating and the smell of blood was very strong. I stayed wrapped like that for about a week.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Shadi says he refused to confess, and eventually he was presented to Air Force Intelligence Head Jamil Hassan. The general ordered him to stop protesting and sent him home.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] After my release, I was thin and very weak. My mother was upset about what happened to me and said, “I told you not to go to the protests. That’s it, lets stop this altogether.”

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Shadi was under the spotlight. There was a red line under his name and the family name. This family is considered dangerous and should be under surveillance.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I argued with my family a lot during that time. They were against my choices. I told them, “You haven’t seen what’s happening inside the prisons. So you don’t have the right to say that we shouldn’t protest against the regime.”

SARA OBEIDAT:

A few weeks after Shadi got out of prison, he began organizing protests again. This time, he took on a more prominent role.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] The demonstrations became more organized than before. I was the youngest person in the protest coordination committee.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Word spread that if any of the coordinators got arrested, they’d be killed so that the protests would stop. Shadi was one of those people.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Were you scared of getting arrested?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] From the beginning of the revolution, my siblings and I agreed that once we joined there were two possible outcomes. We’d either get arrested or we’d die.

November 2011

SARA OBEIDAT:

Nine months into the uprising, thousands of protesters had been arrested and an estimated 3,000 had been killed. Facing international criticism, President Assad went on U.S. television and tried to distance himself from the actions of the security forces.

Bashar Al-Assad

Barbara Walters interview, 2011

BARBARA WALTERS:

Do you think that your forces cracked down too hard?

BASHAR AL-ASSAD:

They are not my forces. They are military forces belong to the government. I don’t own them. I’m president, I don’t own the country, so they’re not my forces.

BARBARA WALTERS:

No, but you have to give the order.

BASHAR AL-ASSAD:

No, no, no. In the constitution, in the law, the mission of the institution to protect the people, to stand against any chaos or any terrorist.

FEMALE VOICE:

[Speaking Arabic] Look, they’re taking another person. They’re going to hit him. Look at how they’re hitting them.

SARA OBEIDAT:

The former security officials we spoke to said they would round people up from where they lived, worked or even prayed. But the demonstrations continued to grow, as did the regime’s wanted list.

Syrian State TV

MALE ANNOUNCER:

[Speaking Arabic] Wanted: Shadi Bin Nabil Haroun. His mother’s name is Wisal. His date of birth is Jan. 30, 1984.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I kept changing my location. I moved to the center of Damascus. I went to my uncle’s house. The security forces raided that house. Air Force Intelligence contacted everyone I know.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] We had spies and people working for the regime. There’s someone in every city and in every neighborhood. As an intelligence officer, hotel owners would come to me and report who stayed with them.

SERGEANT “OMAR”:

[Speaking Arabic] You could find [informants] wherever you go. They could be a taxi driver, they could be a plumber, a mobile phone shop owner, a guy selling cigarettes.

People were living in fear. Your neighbor could be an informant and overhear you talking and tells the security forces about you so they’d come and take you. This is why we’d say, “The walls have ears.”

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] My mother started insisting that I go to see her. I was getting pressured to stay at my aunt’s house.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] It was the Eid holiday and our extended family came to visit. So people found out that we were staying there.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I said, “We have to leave this house. Somebody is watching us.” I packed my things and was about to leave when I saw the soldiers pull up in a bus.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] They came into the house and made their way to our room. The way they conducted the raid was strange. It was as if someone from the house was guiding them.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] They raided the house and took me and Hadi. [Laughs] Intelligence officers took us.

I remember saying to my brother, “I think we might be held here for a long time.”

Harasta Branch

Air Force Intelligence

SARA OBEIDAT:

In December 2011, the brothers say they were taken to Harasta, an Air Force Intelligence branch on the outskirts of Damascus. Col. “Zain” was second-in-command there at the time.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] At that time, the place I worked in was very famous for its bloody practices and the number of detainees held there. We would pack 400 detainees in a room that was 8 by 10 meters. Those who entered would walk over the bodies of the detainees. You couldn’t see the floor.

December 2024

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] This is the changing room, where they would strip off our clothes. Look at all the files on the floor. This is a detainee’s file. Let’s go and check inside.

This is the interrogation room. These are the solitary confinement cells.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] The main solitary confinements.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] These are solitary confinements.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] You could spend months or even years in here.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] I had no authority at all to open the door to let someone out from the prison. That was exclusively up to Jamil Hassan.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] During the first few days at Harasta, Jamil Hassan came to the investigation. He said, “Harouns, I caught you and you are now under my feet.” And stuff like that. He told me, “Don’t count the days, you’re here for life.”

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Do you remember people sleeping on the wall? On the wall above the toilet, they’d sleep there. Someone would sleep here, someone else up there.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] The temperature was around 40 degrees [100 Fahrenheit] because it was crowded.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] We were witnessing strange cases of disease among the prisoners. I think those cases were due to oxygen deficiency because of overcrowding. People would behave very strangely at night and do extraordinary things. These psychotic episodes slowly turned into physical symptoms.

Come and take a look where we were suspended on this pillar, like this, hanging.

We were taken there and hung by our handcuffs from the pipes. It was unbearable and very difficult to withstand. My brother was hung behind me.

For almost 72 hours, three days, same position, without food or drink before the interrogation, as far as I remember.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] The interrogation room was right underneath my office. The screams would reach—everyone heard the screams. Everyone knew how the interrogations were conducted.

There was nothing I could do, my hands were tied.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Don’t you think your silence or your inaction allowed these criminal acts to happen on your watch?

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] My silence? If I spoke one word, I would sentence myself to death.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] But you were highly ranked, maybe higher than others working there.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] Yes, I was the second-in-command in that branch, right below the head of the branch.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] You didn’t try?

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] No, I didn’t.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] So, you decided not to think about these people?

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] Look, Sara, just trying to interfere for the sake of a detainee, you sentence yourself to death.

WARRANT OFFICER “ABBAS,” Air Force Intelligence:

[Speaking Arabic] In my opinion, every human being has two souls—an evil soul and a good soul. They are in a constant state of war. One of them is telling you to think and have empathy. The other is telling you to be selfish and destructive, saying, “You’re an agent of this regime. Keep quiet. Or you’ll die.”

SARA OBEIDAT:

Warrant Officer “Abbas” told us about his first day of training at Air Force Intelligence as a young recruit.

WARRANT OFFICER “ABBAS”:

[Speaking Arabic] We were taken to Damascus. As soon as we got off the bus, two people ran toward us. They both had batons and they started beating us. They said, “Shoes off, clothes off.” They made us strip down to our underwear.

This style of reception is well known in Syria. The psychological torture is meant to break your spirit.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Why? What are they hoping to achieve?

WARRANT OFFICER “ABBAS”:

[Speaking Arabic] First, they want you to stop behaving like a civilian. More important, it instills a sense of fear so that [the soldier] doesn’t refuse an order. So that soldier never says no or disobeys. So that was the objective.

MALE VOICE:

[Speaking Arabic] Attention.

SCHOOLCHILDREN:

[Speaking Arabic] Ba’ath!

“HUSSAM,” Military Police:

[Speaking Arabic] We loved the regime. We loved it out of fear.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Before joining the military, “Hussam” grew up in a rural part of Syria where opportunities were scarce. He told us that he and his classmates were taught that the Assads were the saviors of Syria.

SCHOOLCHILDREN:

[Speaking Arabic] God, Syria, Bashar only!

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] We had a book at school called “National Education.” I’m not sure if it exists in other countries. It was all about Hafez al-Assad, the immortal leader, and stuff like that. They made us memorize it just like a religious text.

I reached ninth grade and left school without a diploma. I remember the slogans of the National Party:

“One Arab nation, bearing an eternal message: Our goals are unity, freedom and socialism,” every day and repeatedly.

We have mandatory military service in Syria. When I turned 18, I started my service. We loved going into the military. We loved the idea of going into the military and getting that experience of becoming men capable of bearing arms in the face of anybody.

They undressed us to be barechested, and they punched us here to see if we could endure it or not. He punched me here. I did not utter a sound. I stood still. He said, “Fine, go over there.”

After 60, 65 days I was deployed to Saydnaya military prison.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Over the course of the war Saydnaya became the most infamous of Syria’s prisons. Built in the 1980s, it had two main buildings: One housed soldiers who were considered traitors. The other was largely for anyone who opposed the regime.

Warrant Officer “Osama” was the chief of staff to the head of Saydnaya prison.

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA,” Chief of Staff, Saydnaya prison:

[Speaking Arabic] The soldiers who worked at the prison and oversaw the prisoners were in good shape. They were physically strong. Most of them came to us through mandatory conscription. None were over the age of 30.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] If they were that young, were they familiar with torture before, or did they learn it there?

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] None of them had seen torture before. They learned inside the prison. Yes.

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] We didn’t leave the prison at all. We had no external communication. No telephone, television, cassette player. Electronic devices weren’t allowed. Our life was only military.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] So Saydnaya became your world?

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] Exactly.

SARA OBEIDAT:

By April 2012, Shadi and Hadi had been detained by Air Force Intelligence for four months.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] They called our names in the morning and they took us outside the branch.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] A big vehicle arrived. It was known as “the meat truck” because it looked like a refrigerator truck for transporting meat. But they used it to transport prisoners.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] We tried to guess where we were going. To court? Nobody knew. When we went in the direction of the valley there was . . . there was a moment of silence. This road only leads to Saydnaya.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] It’s like being in a horror film where people suddenly disappear or die. Everyone was convinced that there was no way out of Saydnaya. I thought that this would be the last chapter of my life.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] What information did you have about the prisoners when they arrived?

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] “This guy participated in a protest and bore arms against the state.” “They were terrorists, and they are not worthy of life.”

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] They took us off the truck. They ordered us to cover our eyes. They said, “Everyone get down on your hands and knees.”

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] I approached them with extreme anger. I beat them with all my strength.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] The blows you’re getting, you don’t know where they’re coming from. “These are terrorists. They are this, they are that.”

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] They [our superiors] would say, “Torture them. Don’t let them sleep at night.” “Throw them a party.” “Welcome them, celebrate them.” “Put them in a grave if you want to.” “Bury them alive if you want to.”

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] In that moment I lost all sense of time or place. Things ceased to happen. Nothing at all.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Would you look them in the eye?

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] In their eyes?

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] The eyes of the prisoners, before you beat them?

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] They were all one mass. Given the idea that was instilled in us, they were all the same.

It is true that I tortured, it is true. I am ashamed of myself. Of course I am ashamed of myself. I should have stopped to think before beating another human being. But today I am exposing the prisons to the outside world.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Officer “Osama,” the chief of staff to the head of the prison, told us that he often tried to stop guards from torturing prisoners.

[Speaking Arabic] Did you know there was a “welcome party”?

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] I told you, it’s inevitable, if you were watching over the soldier, but left for five minutes, he’d do it then. They were doing such things on their own accord.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] So, based on what you’re saying, you had no real authority in the prison?

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] I did have authority, as long as I was present. If I told someone not to do something, they’d do it anyway when I left.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Do you consider that good management?

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] It’s not about good management, it’s just not. What can I tell you?

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Could it be that there was indifference toward such things?

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] Maybe, it’s possible, yes.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] We were tortured for hours, and stopped keeping track of time. We heard the doors close but didn’t move for about 15 minutes. We were like this, face down. I started looking to see what was going on or who was here. We opened our eyes one by one and sat down. But when I saw Shadi, I was very pleased that we were in the same room.

December 2024

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] There’s nothing here anymore.

We were this way.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Was that where we could see the afternoon sun?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Yes, at sunset the rays would come through here.

This is 4, and this is 5. This is 6. Until now, it looks the same. That’s it. This is our room at Saydnaya prison. We stayed in it. This is broken here.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Being arrested with someone who means a lot to you is very tiring. I could not stand hearing my brother tortured.

If someone cried out while being beaten, the beating would get worse. Sometimes Shadi had to scream. So I’d scream louder than him. That way they’d take me instead. Because when Shadi suffers, I suffer more for him. I always tried to be the one to take the beating, rather than him. That is my relationship with Shadi. I don’t want anyone to hurt or upset him, especially during the detention.

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] They started calling me whenever they’d bring prisoners. When they’d call me to go and torture them, the prisoners would go back to their cells bloody and exhausted. I felt that I had authority. I felt like I was the president of this prison.

Of course, there were other soldiers like me.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] In every method they used, you’d feel that they have this mindset to make a human feel like an insect, like you are nothing.

It was so easy for a 20-year-old guard doing his military service to stand at the door of the wing and say, “I can make you live, die, eat, sleep, etc. As far as you’re concerned, I am God.”

Our food would come in these buckets. Breakfast, lunch and dinner would come all at once, on top of each other.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] For breakfast, we would get half an egg per person, four olives and one spoon of jam.

You would get used to the routine of Saydnaya after a while. And you’d start to mentally escape the reality. To lighten up the mood, for example, when they gave us bulgur, I would tell the prisoners to

pretend that it was actually fried chicken. I would describe preparing and seasoning the chicken. And then I would portion the food and ask them to taste the chicken. But in reality it was just bulgur. [Laughs] It used to be a regular dish for me, but now I really can’t stand it.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] We look for any papers with names.

This is the ID of the prisoner which is related to the prison. Saydnaya, here it is. This is the most important, this is the prisoner’s identity.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] This is from 2013. Death sentences were executed for 887 people. Until March 15.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] This file says, “Executions from March 11 to May 15, 2013.” Empty as well. It’s empty. These are the execution files that contained the death sentences.

We never knew what happened to anyone who left [the cell]. Did they transfer him to another prison? Did they take him to be executed?

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] They would keep them under harsh torture day and night until they admitted to killing so-and-so. On that basis, they’re sent to the field court, where no questions are asked. It’s just about confirming your statement and signing it with your fingerprint. A month or two later, their sentence would be delivered to the prison.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Inmates were quickly and secretly convicted in military field courts, with no lawyers or right to appeal.

The trials often ended with death sentences, signed off on behalf of President Assad himself. When pressed in public, Assad insisted the killings were lawful.

Bashar al-Assad

Michael Isikoff interview, 2017

MICHAEL ISIKOFF:

Do you know what goes on in that prison? Have you been there?

BASHAR AL-ASSAD:

No, I haven’t been. I’ve been in the presidential palace, not in the prison. [Laughs] First of all, execution is part of the Syrian law. If the Syrian government or institution wants to do it, they can make it legally, because it’s been there for decades.

MICHAEL ISIKOFF:

Secret trials, no lawyers?

BASHAR AL-ASSAD:

Why do they need it if they can make it legally? They don’t need anything secret.

MICHAEL ISIKOFF:

Is that legal in your country?

BASHAR AL-ASSAD:

Yeah, yeah, of course, it’s legal, for decades. In the dependence, the execution, according to the law, after a trial, is a legal action.

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] On Wednesday mornings, back when I worked there, we would have an “execution party.” Our role in executions was to place the rope on the prisoner, then step aside. Only an officer can push the chair out. One time, we put a guy on the rope. [The officer] pushed the chair, the rope tightened, but after 22 minutes, he still hadn’t died. So they told me, “Grab him and pull him downward.” I grasped the prisoner like this and I pulled him down. He still didn’t die. So another guard who’s bigger and stronger said, “Go, I will do it.” Before he died he said one thing: “I’m going to tell God what you did.” Just that, that’s all he said.

SARA OBEIDAT:

An investigation by Amnesty International found that in the first four years of the uprising, up to 13,000 detainees were executed in Saydnaya prison.

The bodies of executed detainees, along with those who died from torture or disease, were taken to military hospitals, where their deaths were registered.

OFFICER “KAMAL,” Army nurse:

[Speaking Arabic] Living detainees would unload the bodies and lay them in the yard.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Officer “Kamal” was an army nurse who worked in a hospital morgue until the final days of the regime.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] Most of the bodies suffer acute weight loss. I mean, resembling a skeleton, which shows they got no food or water. Most of them suffered from skin lesions and rashes due to lack of hygiene. And most as well had torture marks.

SARA OBEIDAT:

His description matches a trove of photographs smuggled out of Syria in 2013 that show nearly 7,000 detainees who died in government custody.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] Unfortunately, during the crisis, it was forbidden for the coroner to write that the cause of death was torture.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] What was usually written as the cause of death?

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] “Heart and respiratory failure.” Even those killed by gunshots were recorded as “heart and respiratory failure.” A doctor is forbidden to write anything more than that.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Over a hundred detainee death certificates we reviewed show the same cause of death: heart and respiratory failure, even in cases where we found evidence the inmates were tortured.

[Speaking Arabic] Not outlining the cause of death helps with concealing a crime.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] We’re not the ones who aren’t clarifying the cause of a death. You have a template, and you write it like that, that’s it. You are forced to write it this way. You say, concealing facts, yes. No one can deny this.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] For us, Hadi and I, as detainees, life was going on. Death, in general, ceased to be what we feared in our lives.

For me it was all about how would I survive? The things that happened the most often and reminded us of the outside world were times like Mother’s Day. We would feel the sadness of loss.

MALE NEWSREADER:

Tens of thousands of people have disappeared in Syria’s jails. Many were tortured to death.

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

The Syrian government has denied claims of abuse.

BASHAR AL-ASSAD:

We don’t have torture policy in Syria. Why do you use the torture for?

MALE NEWSREADER:

Human rights organizations estimate that tens of thousands of people have disappeared since the Syrian conflict began.

MALE NEWSREADER:

Most have been taken from the streets by government security agents, and they’re known as The Disappeared.

MALE SPEAKER:

The numbers are simply striking. We don’t know what happened with them, if they are still in prison, if they have been killed.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] The people who disappeared inside the branches, do you think they can be found?

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] It’s very difficult, very difficult, unfortunately.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] As the days went by, I felt like I’m never going to get released. During the first period of my incarceration, I hoped that I would have a second chance at life. But [those feelings] went away.

SARA OBEIDAT:

By 2019, Assad’s forces had largely put down the uprising. Shadi and Hadi had spent years being transferred from prison to prison and were back at Saydnaya. One day that summer, they were summoned to see a judge.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I entered the judge’s room, and he was on his own. I realized that it was the first day of Eid holiday, so the judge had put out chocolates. He said, “Sit down. You have to go back to being a good citizen,” and things like that. He said, “I am going to release you now. You can leave.” He gave me chocolate and I left.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] When he returned to the cell I asked him what happened and he said, “I’m free.” So we hugged and said, “We’re getting out.” We finally reached our moment of freedom. Every time I see Shadi I remember that moment.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] How did you feel when you went out?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] I was happy that I was released, but I was extremely disappointed with what I saw after my release. You leave a prison to go to a bigger prison.

It always feels like the people who stayed [living in our town], people who I know, I always felt in their eyes that they blamed it on me. “You are the reason we got to this point.” Those people are my neighbors. I grew up with their kids.

Then there’s the person who’s waiting for his son to be released, like I was, and they don’t know what happened to him. I could no longer stay in that place. I just couldn’t stay. Because they were people who I knew who’d been incarcerated, and I know that they died under torture. [Sighs] I want to take a break.

Southern Turkey

SARA OBEIDAT:

After his release, Shadi went into exile in Turkey. In 2021, the brothers joined a Syrian human rights organization investigating crimes committed by the regime.

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] Hello?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] Hi, my name is Shadi Haroun.

MALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] Hello?

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] If you have a moment, my name is Shadi Haroun. I was a prisoner for 10 years during the revolution. We are working on a project about missing people and mass graves. Can you tell me about yourself?

MALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] I served in Air Force Intelligence. I was witnessing dead bodies arriving every Friday for two months.

MALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] We were riding in a big refrigerated truck, sitting among the corpses.

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] I had a brother in prison. That’s why I got into this line of work.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] And your brothers are still missing?

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] Samer is missing, but Mohammed was killed.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] We need to expose the mass graves that the regime is denying.

MALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] Yes, there are mass graves located before you get to Dumaire and the cement factory.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] The regime can get rid of evidence at any time. If that happens, justice will not prevail for the victims and their families.

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] Even looking through the window was dangerous. We could see trucks bringing bodies to the mass graves.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] OK, in this picture you can clearly see someone is digging.

FEMALE VOICE [on phone]:

[Speaking Arabic] Yes, it’s clear.

YUSUF OBEID, Bulldozer driver:

[Speaking Arabic] My love for construction vehicles comes from my dad, who drove them—excavators and bulldozers, etc. There’s a saying, “The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.”

SARA OBEIDAT:

Yusuf worked for the city of Damascus as a bulldozer driver. He’s allowed us to use his real name. He says that a few months into the uprising, an intelligence officer ordered him to take his bulldozer to Najha cemetery on the outskirts of the city.

YUSUF OBEID:

[Speaking Arabic] There was an armed agent. He said, “Follow me,” and drove in front of me. He arrived at the cemetery entrance and I followed him. We continued until there were no more graves. He told me to dig a large 15×15 meter pit, at least 3 meters deep.

December 2024

YUSUF OBEID:

[Speaking Arabic] A black Mercedes arrived, followed by two large, refrigerated trucks, then a military truck carrying soldiers. I started to smell something. As they got closer there was a horrible stench. Then I realized what was inside those fridge trucks. It smelled like rotting dead bodies.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] I’d estimate we had two or three trucks going out every week for burials.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Officer “Kamal” told us the dead bodies were piling up in the morgue at the military hospital where he worked. He says that security forces took him and some of his colleagues to several locations, including Najha cemetery.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] We were asked to drag the corpses out of the truck and into the pit.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] So you put bodies into mass graves?

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] That is what we were told to do.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] What condition were the bodies in?

YUSUF OBEID:

[Speaking Arabic] If my own brother were among them, I would not be able to recognize him.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] On each body, there was a unique number related to the branch.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Where would they write that?

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] On their foreheads or on their chest.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] The numbers indicated that the regime has a full archive of those dead bodies. The first digit is the number of the detainee or the dead body in the hospital and the number of the branch where he was held. And sometimes they’d put a third number, which is their case number.

The regime has a record of everyone who entered their facilities and every move the detainee took. These missing people were subjected to a system of forced disappearance. Then they’re taken and buried in a mass grave where nobody will know anything about them.

YUSUF OBEID:

[Speaking Arabic] I filled the pits with soil to bury the bodies. I made the land look like it did before. So that the employees from the cemetery could bury people above them. Hiding the mass graves underneath the graves of ordinary people.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Yusuf says he stopped working for the government in 2013 and later fled Syria. He’s given testimony about the mass graves at Najha cemetery and elsewhere to the U.S. Congress.

YUSUF OBEID:

[Speaking Arabic] The work was very lonely. All over the world, machine operators are known for building things, right? To build things, not to dig holes [for mass graves]. That only happened under Bashar al-Assad.

SARA OBEIDAT:

We’ve been told by human rights investigators that there are around 130 suspected mass graves across parts of Syria once controlled by the regime. And new ones are still being found. Officer “Kamal” gave us the location of a previously unknown site in an area called Maarouneh, in a military zone between Damascus and Saydnaya. He says he went there once in 2014.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] The hole had already been dug before I got there. It seems that they had done that multiple times before I joined that team.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Do you remember how many corpses were there?

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] About 300 bodies.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Was this location known to the public?

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] No.

March 2010

SARA OBEIDAT:

We’ve obtained satellite imagery of the location and had it independently analyzed. This is what it looked like before the protests began.

May 2012

SARA OBEIDAT:

And this image, from 2012, shows that several large pits appeared in the first 18 months of the uprising. Officer “Kamal” agreed to take one of our colleagues to Maarouneh to film the site.

MALE VOICE:

[Speaking Arabic] You can tell that the ground has been disturbed here. And you can even see the tracks from a large vehicle.

SARA OBEIDAT:

We also spoke to a truck driver, who told us he transported more than 3,000 bodies there over a period of 8 months.

With so many suspected grave sites across Syria, it could take years to investigate them all.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] Tens of thousands of detainees were buried and no one knows anything about them. So you’d have to conduct tens of thousands of DNA tests to find out who each of these people are.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Based on what you’re saying, the only conclusion is there are people who were buried, and their identities could be lost forever.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] Yes, definitely.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] What do you see when you look in the mirror?

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] You might not believe me if I told you. It’s been two or three years since I last looked in a mirror. I can’t bear to look at myself.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Why?

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] You feel like there’s a monster in front of you, a psychological monster beating your mind and body. Because it turned out that we were beating and incarcerating our own people, our brothers. We were brainwashed. We did exactly what the regime and the state wanted us to do.

SARA OBEIDAT:

“Hussam,” the prison guard, defected at the end of 2012 and fled Syria. Since then, he has given testimony and information to human rights investigators about what happened at Saydnaya prison.

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] The main reason I defected was because I felt guilty. All I cared about was to stop inflicting injustice on the people. I side with our people, with my family, with my homeland against the regime.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] If you think of the person who inflicted the most torture on you, if you could speak to that person face to face, what would you say to him?

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] All I want is for one of those officers, or anyone who tortured, to tell me why. I want him to know what it feels like to be missed by your wife, children or mother. He needs to experience that feeling of imprisonment or exile from Syria, or anything.

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] My mind drifts off for long periods of time. My children and my wife try to talk to me, but I don’t respond.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Did you ever tell your kids what you did?

“HUSSAM”:

[Speaking Arabic] No. I will do my best not to tell them. I told my wife the basics, but I didn’t tell her everything. This is something that makes you feel really lonely. But it’s something you can’t ever talk about.

HADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] The officers I would consider to be the good ones are those who left within the first year of the revolution. Those who did not defect from the system or leave Syria I consider to be bad people.

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] In my opinion, we can’t make a definitive judgment. Saying, for example, “Whoever defected early is innocent, while those who defected later should be held accountable.” I went through the experience of defecting, and it was extremely dangerous.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Col. “Zain,” second-in-command at Harasta Intelligence branch, has been living in hiding since leaving Syria. He’s provided information to human rights investigators but insists he had no direct involvement in torture or killing.

[Speaking Arabic] We spoke to many people who said, “I had nothing to do with it.” So who? Who should be held accountable?

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] Everyone who participated in killing innocent people should be tried.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Don’t you think you should be held accountable because—

COLONEL “ZAIN”:

[Speaking Arabic] If anything’s proven against me, I’m ready for trial. If anything is proven against me, I am ready for trial.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] Do you have anything to say to the families of the prisoners of Saydnaya?

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] Well, no matter what anyone says, it can’t improve their situation or compensate them for what happened.

SARA OBEIDAT:

In 2013, “Osama’s” boss, the head of Saydnaya prison, was captured and killed by Syrian rebels. Shortly afterwards, “Osama” fled the country. He went on to help human rights groups gathering evidence of the atrocities that took place in Saydnaya.

[Speaking Arabic] Do you sleep well?

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] Yes, thank God. In my opinion, I’m satisfied with how I did my job.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] When we speak to people who were detained, they say that what they want most is some kind of accountability.

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] Yes.

SARA OBEIDAT:

[Speaking Arabic] They want people to acknowledge that “This did happen to you. We failed you. We didn’t protect you.” But I hear no sense of responsibility in your words.

WARRANT OFFICER “OSAMA”:

[Speaking Arabic] Because I can’t. I did everything I could. I can’t, for example, give myself a position or take on a responsibility that was bigger than me and my position. There are people who might not accept what I’m saying, I know that. But I’m telling you what I did and what happened.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] Yes, we were forced to do a job, but we didn’t want to do this job. If we didn’t, we would end up killed, similar to our brothers who were detained.

SARA OBEIDAT:

Officer “Kamal” is still in Syria. After the regime fell, he gave his account of what happened at the hospital and the mass graves to the new government. Four of his former colleagues, as well as multiple detainees, accuse him of abusing prisoners. He denies this.

OFFICER “KAMAL”:

[Speaking Arabic] If I’m accused of something, I will defend myself. If I’m guilty, I wouldn’t face anyone or be here in front of you. I wouldn’t allow you or anyone else to see me. If you or society look at me as a guilty person, tell me how I am guilty.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] If these people didn’t go to work or rejected their jobs because Syrians are being eliminated inside the security branches, would this security branch still be operating? No. The head of a security branch cannot operate it alone. Whatever someone’s position was, they contributed to this process. They are just like anyone else who contributed to the survival of this regime.

December 2024

Bashar al-Assad has been granted asylum in Russia.

A French court is seeking his arrest for complicity in crimes against humanity.

Major General Jamil Hassan has been charged by the United States for war crimes, and convicted in a French court for crimes against humanity.

His whereabouts are unknown.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] There’s something I really need to say. And many other detainees would feel the same. We’re still alive, but we’ve lost something. Something is missing. This joy, this happiness is not complete just because we’re free. Everyone, the detainees and families of the missing, should keep talking about this. All the decision-makers who had a role in oppressing the Syrian people escaped and are now in hiding. They’ve left everyone to pick up the pieces. They’ve left us to deal with what they left behind.

MALE VOICE:

[Speaking Arabic] I’m looking for 10 names, that’s Ahmed. Check this one!

FEMALE VOICE:

[Speaking Arabic] Assaf.

SHADI HAROUN:

[Speaking Arabic] We’ve become a divided society. I don’t know how we’re going to move forward and heal our wounds and rebuild this country. We’re living this dichotomy of victim and perpetrator, or victim and culprit. It’s hard to decide who should be held accountable and who should be forgiven.

Everyone has their own narrative. Everyone has their own story.

DIRECTED BY Sasha Joelle Achilli Sara Obeidat

PRODUCED BY Amel Guettatfi Saad Al Nassife Sara Obeidat

NARRATED BY Sara Obeidat

CO-PRODUCED & EDITED BY Andrew Pattison, ACE

SENIOR PRODUCER Dan Edge

DIRECTORS OF PHOTOGRAPHY Zach Caldwell Joshua Baker Brendan Easton

ADDITIONAL CAMERA Tarek Turkey Mikhail Galustov Mani Benchelah Sasha Joelle Achilli Mohammed Nizar Mokhel

ADDITIONAL EDITING Nazim Kadri-Zade

PRODUCTION EXECUTIVES Rebecca Lavender Lisa Megarry

PRODUCTION MANAGERS Rachel Martinez Phil Kingwell Olivia Badnell Toby Keeley

PRODUCTION COORDINATORS Carolyne Astbury Rory Boyle

PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT Ellis Green

LOCATION PRODUCERS Oudai Hussein Zeynep Bilginsoy

LOGISTICS – TURKEY Hakan Ozdemir

ORIGINAL MUSIC Firas Abou Fakher

COLORIST Sonny Sheridan

ONLINE EDITOR Dicky Everton BFE

ADDITIONAL ONLINE EDITOR/COLORIST Jim Ferguson

SOUND MIX Jim Sullivan

DIGITAL TECHNICIAN Nicola Theodoulides

HEAD OF DEVELOPMENT Victoria Musguin-Rowe

DEVELOPMENT RESEARCHER Sheida Kiran

ADDITIONAL RESEARCH Firas Al Sweiha Hussam Hammoud Karam Shoumali Mohammad Al Hammoud

IMPACT PRODUCER Laura Gaynor

ARCHIVE PRODUCER Stuart Robertson

ADDITIONAL ARCHIVE RESEARCH Omar Al Ghazzi

GRAPHICS Chris Salvador

TRANSLATION Takwa Masadeh Saga Translations Saman Jaff

SATELLITE IMAGE ANALYSIS Jonathan Drake

ARCHIVAL MATERIAL Talal Derki Getty Images / Andalou Getty Images / ITN The Open University Reuters Saqba News Shutterstock

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL ABC News Yahoo! News

FOR BBC

COMMISSIONING EDITOR Joanna Carr

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Sarah Waldron

ORIGINAL PRODUCTION FUNDING PROVIDED BY Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Abrams Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Park Foundation, FRONTLINE Journalism Fund with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler through the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, additional support from Koo & Patricia Yuen and from Laura DeBonis & Scott Nathan.

FOR FRONTLINE

POST PRODUCTION MANAGER Tim Meagher

SENIOR EDITOR Barry Clegg

EDITOR Brenna Verre

EDITORS Christine Giordano Joey Mullin

PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Hinako Barnes

ASSISTANT EDITORS Thomas Crosby Julia McCarthy

FOR GBH OUTPOST

SENIOR POST PRODUCTION MANAGER Beth Godlin Lillis

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY Tim Mangini

INTERN Nicholas Doyle

SERIES MUSIC Mason Daring Martin Brody

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT Ellen O’Neill

DIRECTOR OF IMPACT AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS Erika Howard

SENIOR DIGITAL WRITER Patrice Taddonio

PUBLICITY & AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT COORDINATOR Julia Heffernan

ASSISTANT DIGITAL EDITOR Ambika Kandasamy

ASSOCIATE DIGITAL EDITOR Mackenzie Wright

DIGITAL PRODUCER / EDITOR Tessa Maguire

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS Anne Husted

PODCAST PRODUCER Emily Pisacreta

ARCHIVES & RIGHTS MANAGER John Campopiano

SENIOR BUSINESS ASSOCIATE Sean Gigliotti

FOR GBH LEGAL Eric Brass Suzy Carrington Jay Fialkov

SENIOR CONTRACTS MANAGER Gianna DeGiulio

SENIOR BUSINESS MANAGER Sue Tufts

BUSINESS DIRECTOR Mary Sullivan

SENIOR DEVELOPER Anthony DeLorenzo

LEAD, DIGITAL DESIGN & INTERACTIVE Dan Nolan

FRONTLINE/COLUMBIA JOURNALISM SCHOOL FELLOWSHIP TOW JOURNALISM FELLOWS Jala Everett Refael Kubersky

FRONTLINE/NEWMARK JOURNALISM SCHOOL AT CUNY FELLOWSHIP TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW Sunny Nagpaul

FRONTLINE/MISSOURI SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM FELLOWSHIP MURRAY JOURNALISM FELLOW Kristina Abovyan

PBS CREATIVE VOICES FELLOWSHIP DIGITAL PRODUCER Tasnia Choudhury

ARCHIVAL PRODUCER Coral C. Salomón Bartolomei

SENIOR DIGITAL PRODUCER / EDITOR Miles Alvord

SENIOR DOCUMENTARY EDITOR & PRODUCER Michelle Mizner

DIGITAL EDITOR Priyanka Boghani

STORY EDITOR & COORDINATING PRODUCER Katherine Griwert

POST COORDINATING PRODUCER Robin Parmelee

SENIOR EDITOR AT LARGE Louis Wiley Jr.

FOUNDER David Fanning

SPECIAL COUNSEL Dale Cohen

SENIOR PRODUCERS Dan Edge Frank Koughan

SENIOR EDITOR & DIRECTOR, LOCAL JOURNALISM Erin Texeira

SENIOR EDITOR, INVESTIGATIONS Lauren Ezell Kinlaw

MANAGING DIRECTOR Brian Eule

MANAGING EDITOR Andrew Metz

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Raney Aronson-Rath

A BBC Current Affairs production for GBH/FRONTLINE and BBC

© 2025 BBC All Rights Reserved

Additional Materials © 2025 WGBH Educational Foundation All Rights Reserved

FRONTLINE is a production of GBH, which is solely responsible for its content.

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.