Two Strikes

September 5, 2023

20m

Produced with The Marshall Project as part of FRONTLINE’s fellowship with Firelight Media, "Two Strikes" examines how a former West Point cadet got life in prison under a "two strikes" law

Two Strikes

September 5, 2023

20m

Share

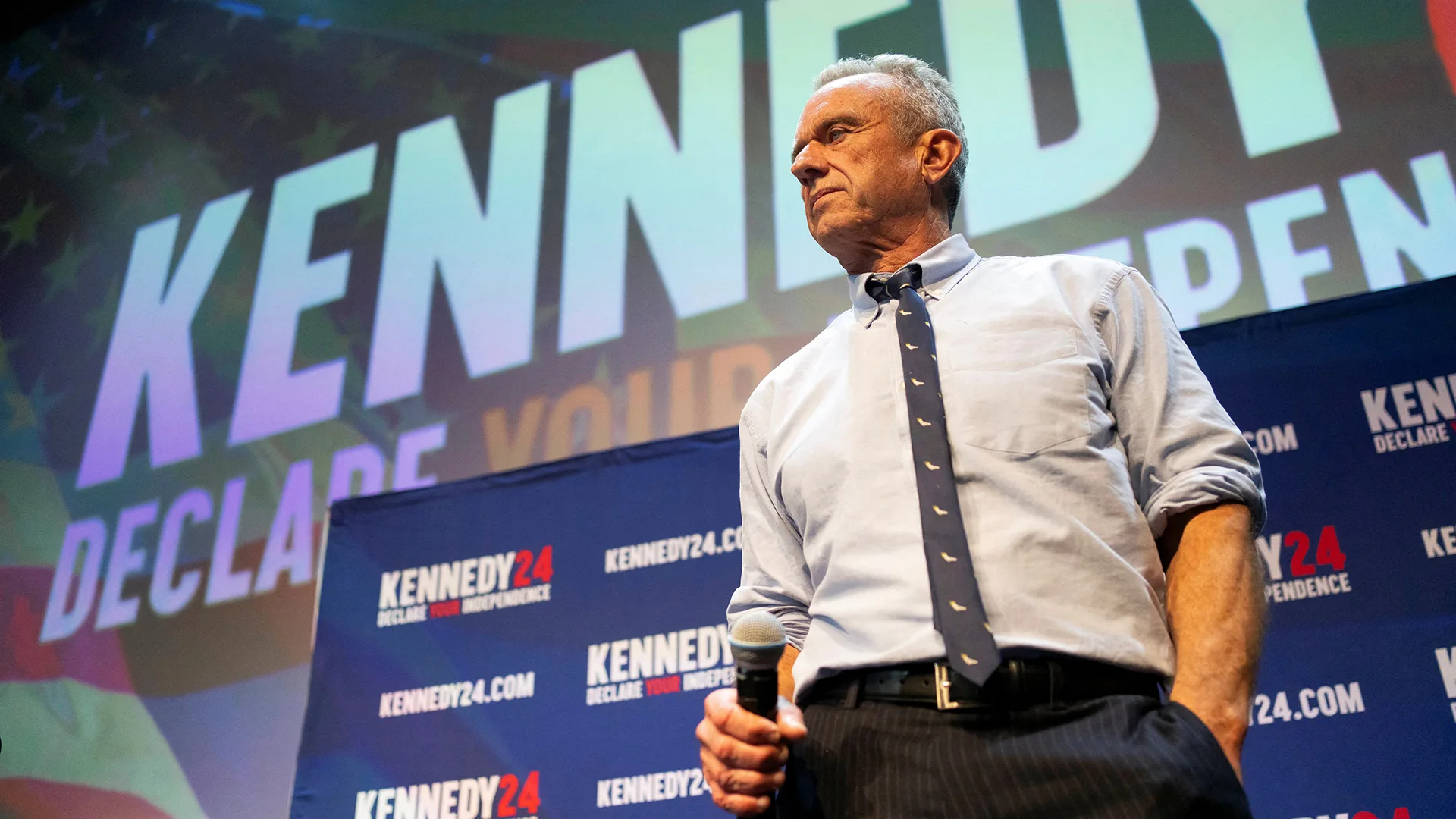

Two Strikes, a film produced with The Marshall Project as part of FRONTLINE’s fellowship with Firelight Media, examines the impact of a little-known “two-strikes” law.

The documentary tells the story of how a former West Point cadet struggling with PTSD and alcoholism got life in prison in Florida after an attempted carjacking — a sentence that even the victim viewed as too harsh.

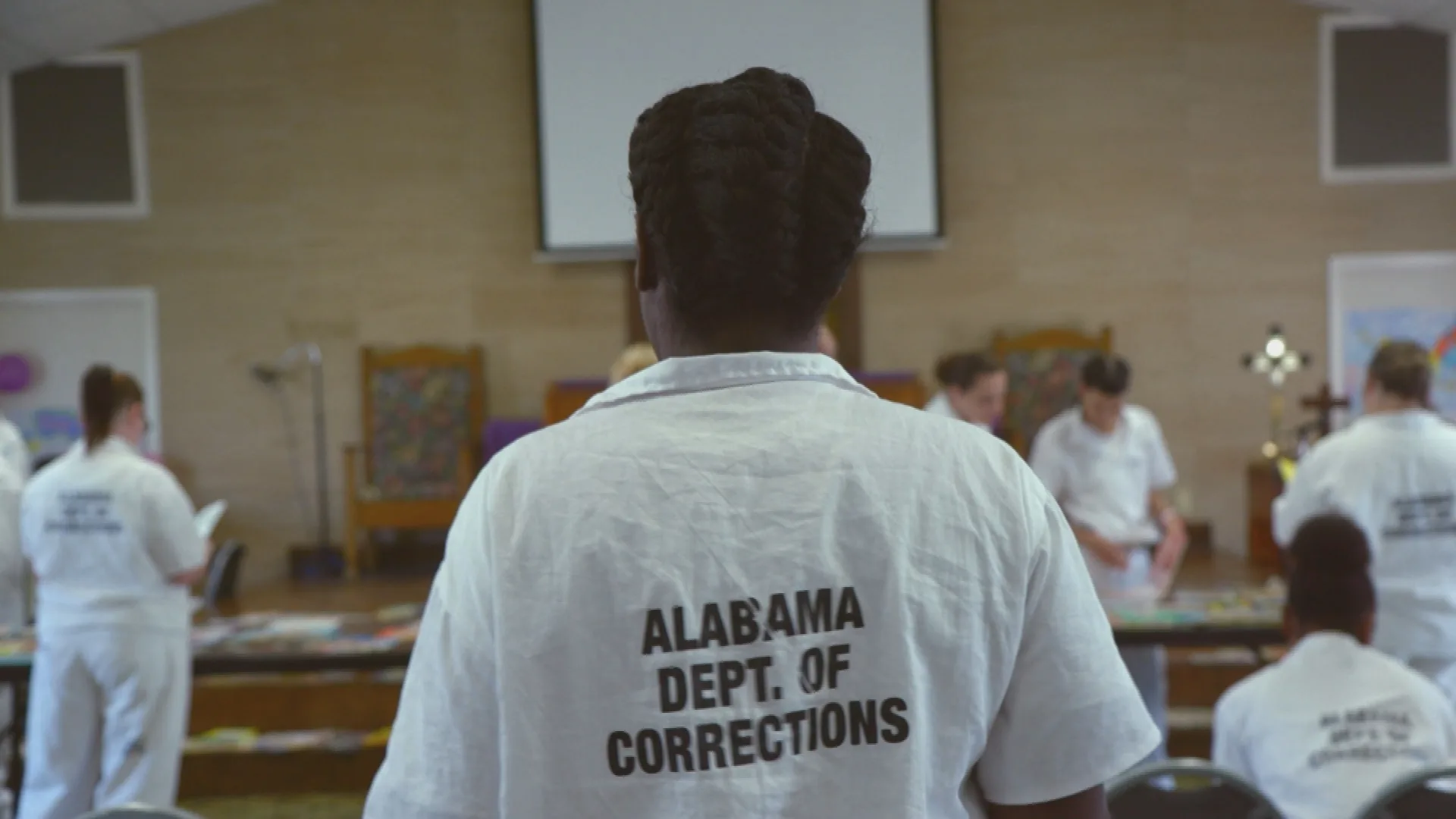

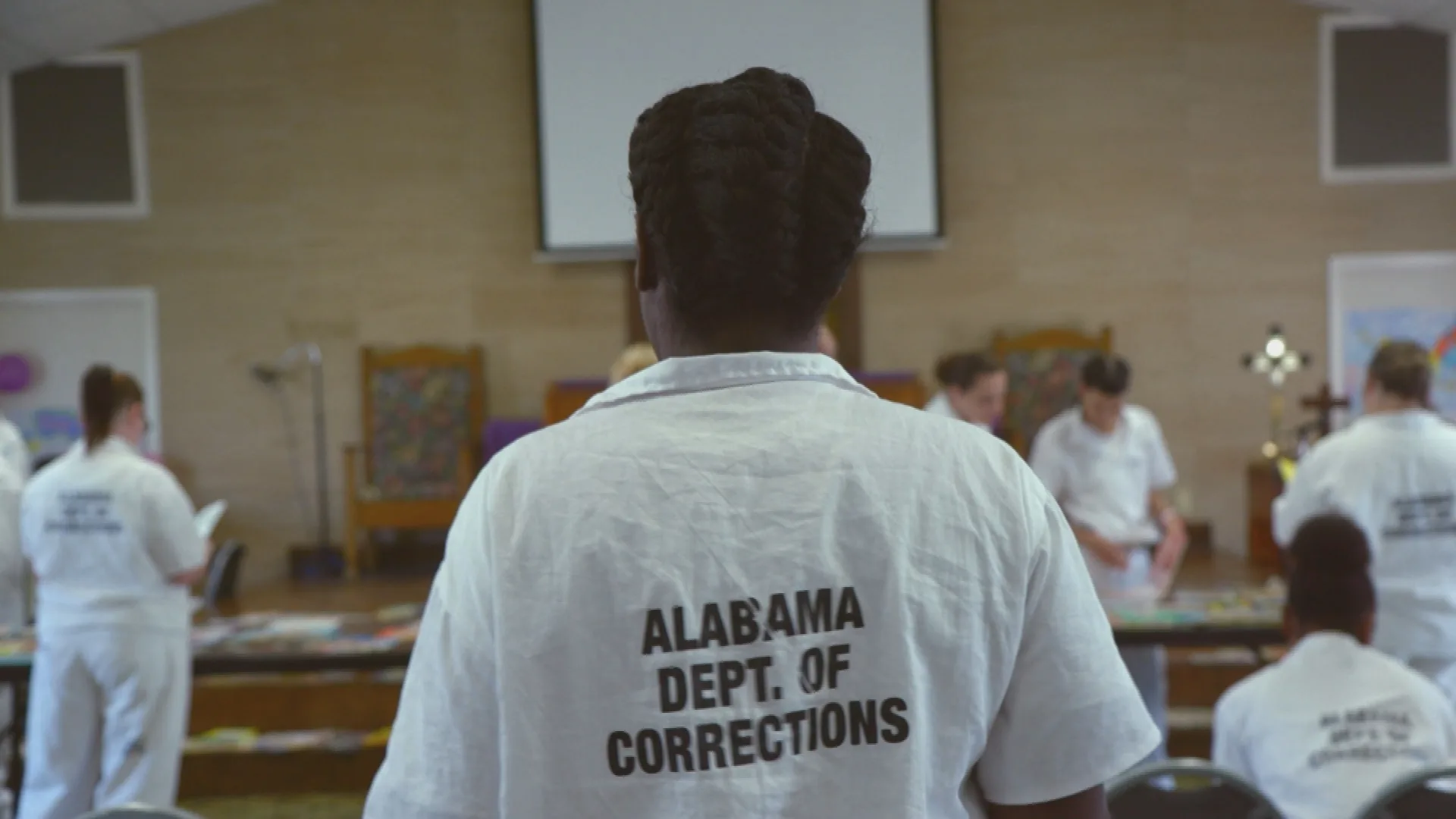

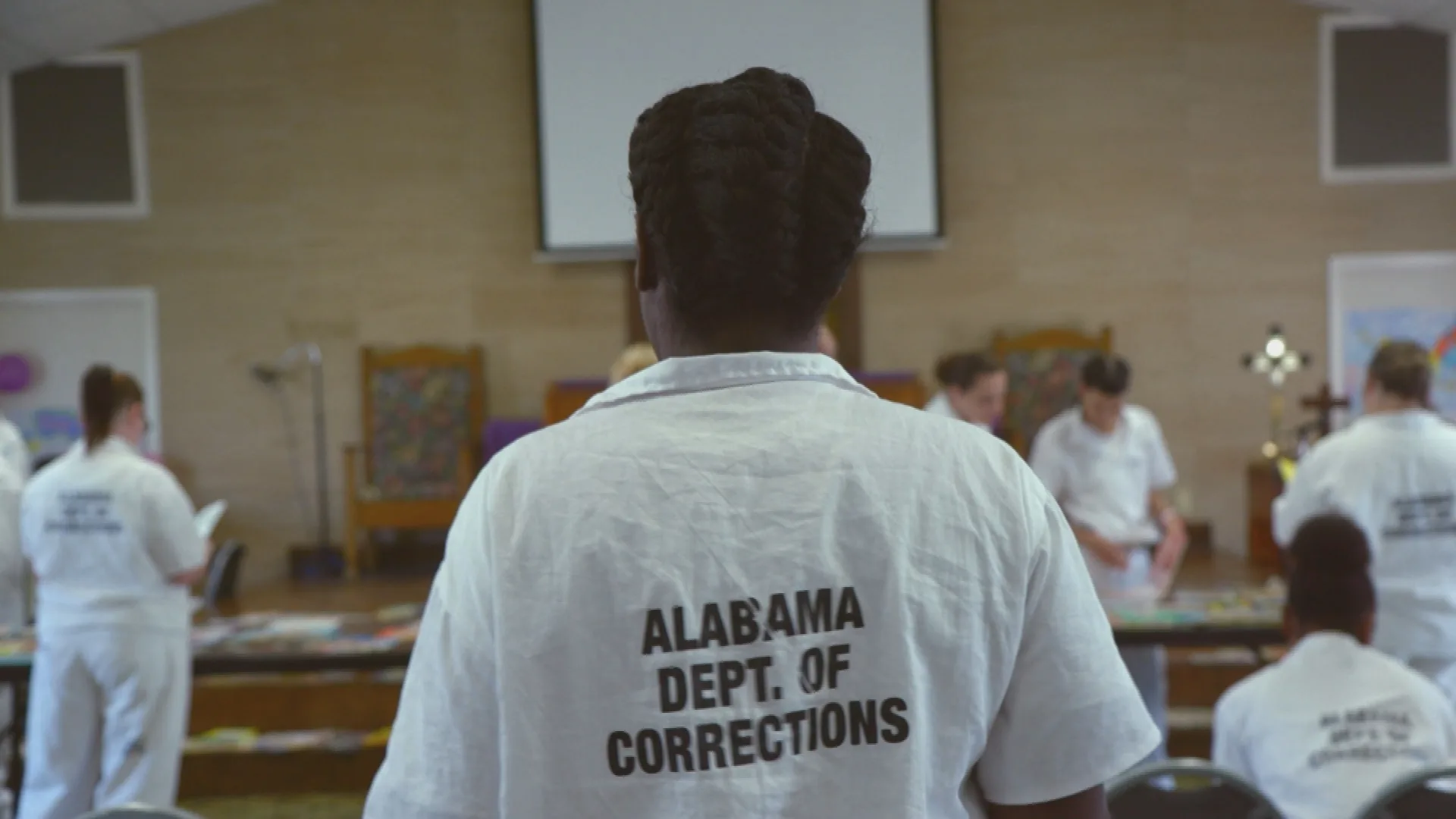

Also in this two-part hour, Tutwiler, a look at pregnant women in prison and what happens to their newborns.

Directed by

Produced by

Transcript

Credits

Journalistic Standards

Support provided by:

Learn More

Most Watched

The FRONTLINE Newsletter

Two Strikes and You’re in Prison Forever

The Making of ‘Two Strikes’: A Conversation With the Filmmaker and Reporter

Tutwiler

Related Stories

The Making of ‘Two Strikes’: A Conversation With the Filmmaker and Reporter

Florida’s ‘Two-Strikes’ Law Put Him in Prison for Life. Even His Victim Said It Was Too Harsh.

‘The Only Way We Get Out of There Is in a Pine Box’

Her Baby Died After Hurricane Katrina. Was It a Crime?

He Got a Life Sentence When He Was 22 — For Robbery

Two Strikes and You’re in Prison Forever

Life Without Parole Is Replacing the Death Penalty — But the Legal Defense System Hasn’t Kept Up

Tutwiler

Locked Up for Life After ‘Two Strikes’

“Two Strikes” and “Tutwiler”

Related Stories

The Making of ‘Two Strikes’: A Conversation With the Filmmaker and Reporter

Florida’s ‘Two-Strikes’ Law Put Him in Prison for Life. Even His Victim Said It Was Too Harsh.

‘The Only Way We Get Out of There Is in a Pine Box’

Her Baby Died After Hurricane Katrina. Was It a Crime?

He Got a Life Sentence When He Was 22 — For Robbery

Two Strikes and You’re in Prison Forever

Life Without Parole Is Replacing the Death Penalty — But the Legal Defense System Hasn’t Kept Up

Tutwiler

Locked Up for Life After ‘Two Strikes’

“Two Strikes” and “Tutwiler”

Voice Actor

VOICE ACTOR [reading Eunice Hopkins testimony]:

It was so hot I barely could see. I opened all the windows to let the hot air go up. I got in the car. He was white, kind of young man. He had a hat, a cloth hat, and T-shirt with no sleeves and shorts and tennis shoes.

MARK JONES:

For what am I arrested for now?

MALE POLICE OFFICER:

Attempted carjacking

MARK JONES:

Great.

VOICE ACTOR [reading Eunice Hopkins testimony]:

He grabbed my left arm and told me to get out and give me your keys.

MALE POLICE OFFICER:

Did you try to take her car?

MARK JONES:

If I want to take her car, I could take a car. It’s no problem.

VOICE ACTOR [reading Eunice Hopkins testimony]:

I screamed, and screamed, and screamed. He left.

MARK JONES:

You think I carjack people, dude? For real? I don’t f—— do that s—, man.

MALE POLICE OFFICER:

Well, we got a witness, and the lady said that you were trying to take her car.

VOICE ACTOR [reading Eunice Hopkins testimony]:

I was so scared, scared to death.

MALE POLICE OFFICER:

Mark, here we are. You’re just going to go into the facilities and just do what they say, and hopefully you can get out of here soon enough, all right?

MARK JONES:

Won’t be soon enough. I’ve got to do—I’ll be here for at least eight months, nine months.

MALE POLICE OFFICER:

No, you won’t.

MARK JONES:

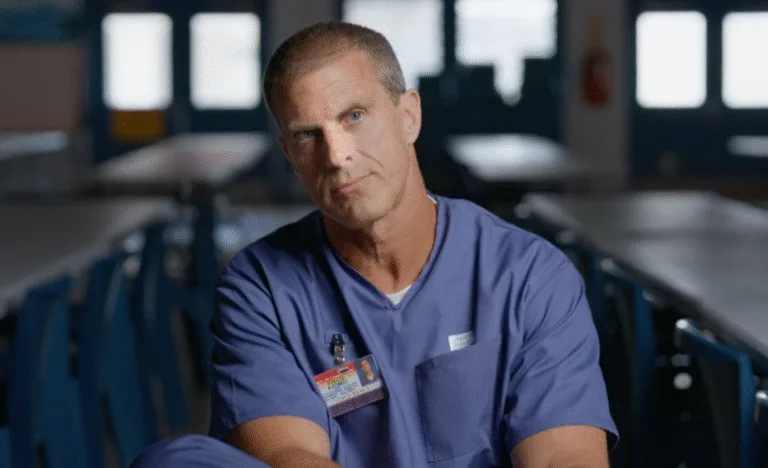

My sentence is life without the possibility of parole. So, I’m in here till I die.

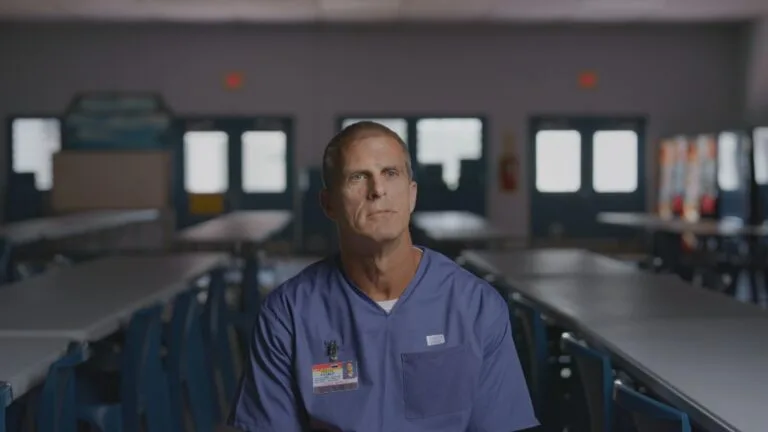

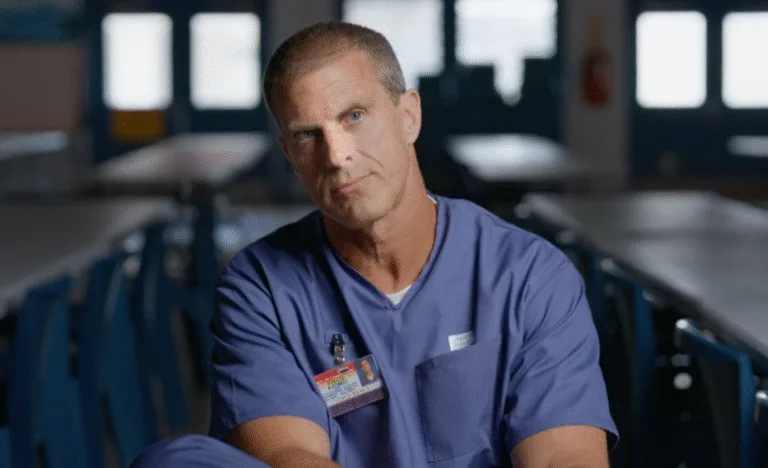

MARK JONES:

It’s a hard place to navigate. There’s a lot of different people from all walks of life. So you’ve got to be careful.

It still doesn’t seem real. I’m 48 now. The average male lives to about 78 years old, which means I’ll do another 30 years in here before I pass away, on average. I’m reasonably healthy, so I might make it till my 80s, so—It’s a—It’s a long time.

ROSE JONES, Mark’s wife:

I have a bunch of stuff here. Boxes and things that we have to lift. Mark isn’t there, so he cannot lift things, so I had to lift it. So, that’s one of the things that kind of, you know—You don’t have somebody here to help you. It’s just you.

This is our kitchen. This one was more my mother-in-law. She had those in the house and I always liked it, so I just kind of put the little vase and put it in there.

Got this, it’s one of the little things that I treasure. It’s a bar of VO5 soap. But it’s handmade. So they made that, put my name out and inside, “Always Mark, I love you.” That makes it tougher every time that I see it.

I am a pharmacy technician at Orlando, at the VA. Well, Mark and I have been together for a really [laughs] long time. We had both got out of divorces. I always tell him that he was the only person that I know that goes to the kitchen and do the dishes with me. He’s a good man.

We bought the house this year. Some people say, “Oh, you continue being dumb like you are, married to somebody and paying this and paying that.” But for me it’s not, it’s—like I say, I’m not taking anything with me the day I die, but I will leave him something. So, what is mine is his.

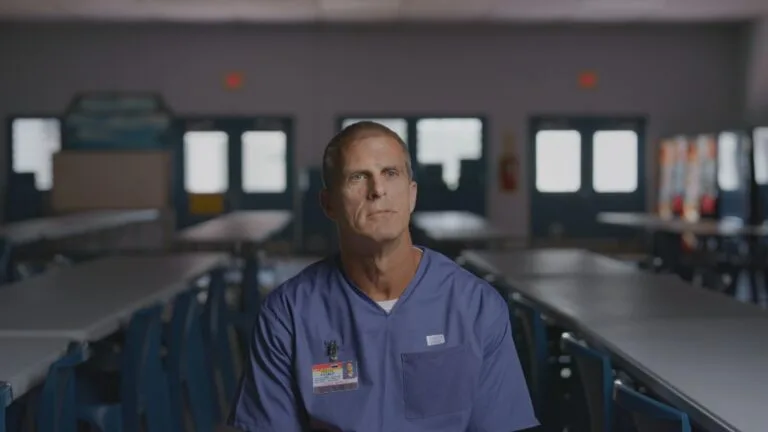

MARK JONES:

I grew up, I was a very patriotic young guy. I wanted to be an FBI agent like my father. Have three kids, have a nice home, maybe coach football. I had an older brother who was a West Point cadet. I had a grandfather who served in World War II. So the military was a big part of our family. And I really believed in America, its principles, its values, freedom.

I enlisted in Fort Dix, New Jersey. And then from there I went into West Point. It was hard. It’s a very competitive place. A lot of patriotic people. Smart people.

I played football there also.

I was there in the early ’90s. But then there were some things, some—There were some violent things that went on, and it was considered normal.

Mark says he was violently assaulted during a hazing incident at West Point.

MARK JONES:

No, I don’t want to get into that. I really don’t. I’m sorry. [Sighs] It was bad. It was really bad. It’s part of my life.

West Point declined to comment.

MARK JONES:

I could tell things weren’t right in my mind. The big thing is the noise. Your heart starts beating really fast. It’s like being electrified, and you can’t figure out what’s causing the electrification. My—Every pore on my body would open up sometimes, and I couldn’t explain why.

I remember my mom, she would call it my “dark place.” She would say, “Mark it’s not real.” It would help bring me back into reality. But whatever was going on, I constantly wanted to take that edge off.

MALE POLICE OFFICER:

How about your family? You got family? You got brothers and sisters?

MARK JONES:

I got family that don’t want me around, dude.

MALE POLICE OFFICER:

They don’t want you around?

MARK JONES:

They don’t want me around, dude. Just, f—. I’m a freak show, man.

I would have really bad nightmares and I would drink during the night to go back to sleep. It wasn’t a lot. And as time progressed, I’m trying to get drunk, I’m trying to stay drunk. All day, all night.

I’d go out a lot on my own just to get away from people. If everybody was quiet around me it would help.

Mark sometimes slept in the woods.

ROSE JONES:

He disappears. I mean, sometimes he disappears for days and you don’t know. It’s just like, you don’t know what was going on. But then, he’d call. “I’m fine,” blah, blah, blah. And so, I’m—I was calm. But then, he’d continue it.

MARK JONES:

That’s not my MO, dude. I’ve never done something like that.

MALE POLICE OFFICER:

So, what is your MO, man?

MARK JONES:

Petty thievery, dude. All right? It’s usually beer. Usually because my check didn’t come in on time, or something like that. So—

I mean, I took these items. I’d go to county jail. And I’d figure my quickest avenue back to alcohol would be probation. And then of course, I would violate the probation, so it just became a collage of incidents.

I really didn’t get help until probably 2010. I went to the Orlando PTSD clinic. Unfortunately, the Orlando PTSD clinic said, “Look, you need a higher level of care.”

ROSE JONES:

So he had to go to Bay Pine. And Bay Pine said, “You have to be sober for one or two months.”

MARK JONES:

So I was kind of bouncing between the two. And I’m, you know, and I’m—I was a mess. I was a mess at that time. A lot of drinking.

ROSE JONES:

So how can you going to tell somebody “do not drink” if you are an alcoholic?

I think that the VA failed Mark.

The VA did not comment on Mark’s case but said it “provides a full continuum of care for enrolled veterans.”

MARK JONES:

Eventually, that’s when the incident that occurred that put me here happened.

I just go by what Ms. Hopkins said happened that day. I mean, I was blacked-out drunk. Apparently, I was at a Publix, talking on my cellphone, and I walked up to a vehicle, leaned in the vehicle, told the person to give me the keys and get out of the vehicle. The victim said they screamed, and I walked away talking on my cellphone.

Tell you one thing I didn’t, strong-arm rob this chick, dude. Don’t put that s— on me, please.

See, the problem was I had gone to prison for grand theft out of a Home Depot; it was a drill. Because I had been released from prison within three years, the state attorney offered me a 15-year plea deal, but he said if you don’t take this plea deal, we’re going to enact what’s called the PRR statute—”prison releasee reoffender.”

MALE VOICE 1:

We could call this bill the “We Really Mean it This Time” bill.

MALE VOICE 2:

People that have committed treason, murder, manslaughter, sexual battery, carjacking, robbery, arson, kidnapping—

MALE VOICE 3:

So what we’re trying to do is put these people back in prison before they commit another crime on a probation violation.

MALE VOICE 4:

Sort of a “two strikes and you’re out,” if you will.

MARK JONES:

If you had been incarcerated three years or less prior, and they decide to enact the statute, and you go to trial, you’re automatically sentenced to the statutory maximum.

I was found guilty at trial. They gave me life in prison.

Anything I say about the severity of my sentence, I don’t mean to minimize the impact I had on her that day. She has every right to have a normal day. And, so I’m sorry. From the bottom of my heart.

When Eunice Hopkins, the victim, heard Mark would be imprisoned for life, she called the prosecutor to complain.

ROSE JONES:

This is another Christmas. “You are in my heart. Be safe, my love. Come back home soon.” This one was from his mom.

When you have somebody in prison, you’re just not putting one person in there. You’re putting the whole family. And—we lost his mom already. It’s—

MARK JONES:

Right before—It was hard. Oh, man. I broke down on the phone.

ROSE JONES:

And he calls, like, every 15, 20 minutes, just for me to put the phone.

MARK JONES:

You know, I’m in Columbia CI prison, I got about 10 people standing around me, and I had to say goodbye to my mom.

ROSE JONES:

Seeing the mother go through the whole thing, him not able to go to hug her. I mean—

MARK JONES:

That’s hard. It’s just a good person. I couldn’t go to her funeral or anything like that at all.

ROSE JONES:

Now, the father is not doing well either. So, it’s very, very—very tough. Very, extremely tough.

MARK JONES:

And this is—these are the last years I’ve got with him.

At first, my dad was like, “Well, you’re—you should go to jail,” and that sort of thing. But as time went on, he was like, “This is enough, Mark,” you know? “I’ve seen so much change in you.”

I’m a law clerk at the prison law library. You got a lot of guys in here with less than a ninth grade education. They can’t even write an essay, let alone put a brief together for the district court of appeal, and they need help.

I’m stuck in here. I’m trying to make a difference from in here, but it’s hard. If there’s any way I can get back to my family, I need to get there. I mean, it’s hard for her because she’s doing everything by herself.

AUTOMATED PHONE VOICE:

—an inmate at a Florida Department of Corrections institution. Your current balance is $55.49. This call is from a correction facility and is subject to monitoring and recording. Thank you for using Global Tel Link.

MARK JONES [on phone]:

Hey, babe.

ROSE JONES:

Hey, honey.

MARK JONES [on phone]:

Well, there’s nothing going on here. I’ll be trying to get a hold of my dad tonight, see how he’s doing.

ROSE JONES:

OK.

MARK JONES [on phone]:

A lot of guys are interested in what I have—

ROSE JONES:

It’s always good to hear his voice. Because you always think, “Is he alive?” But, it’s tough, it’s tough. The phone calls used to be half an hour for $1.20. Now it’s $4.30. They take whoever they can and make money out of the family.

MARK JONES [on phone]:

All right, I love you.

ROSE JONES:

I love you, babe. Bye.

MARK JONES [on phone]:

Have a good night. Bye-bye.

ROSE JONES:

For me, this is just an abuse of power. Not only Mark, because this—It’s all the people that are going through same process and the same pain.

TRACY JOHNSON, PRR family member:

My brother Dwayne has served 21 years on a 60-year prison sentence for the theft of a gold chain.

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

Stuckey shoplifted DVDs from a Seminole County Sam’s Club. He was sentenced to 30 years.

Joshua Lingebach ‒ Armed robbery

Life without parole

Nathaniel Johnson ‒ Armed robbery

Two life sentences

Alexander Patterson ‒ Armed robbery

11 life sentences

SHERIFF GRADY JUDD, Polk County, FL:

I love it, and it works. Crime is at historic lows in Florida. So that tells us that it works.

FEMALE NEWSREADER:

There are currently 8,000 people in Florida prisons sentenced to mandatory maximum sentences under the prison releasee reoffender statute.

Amber Arnesen ‒ Carjacking

30 Years

Virgil Antwon Monts ‒ Armed robbery and kidnapping to facilitate felony

Five life sentences

Mark Jones ‒ Burglary of a conveyance with assault

Life without parole

ROSE JONES:

I go back again to the whole thing. For scaring an old lady. It’s just—it’s just blow my mind. The system have to change. This law have to change. Florida have to change.

MARK JONES:

When you’re in this kind of a place, you miss simple things. You know, just being able to go to Chick-fil-A and get a sandwich. I miss Christmas. I miss the holidays. I just miss my family, you know? I wish I could be there.

If there’s heavy boxes to carry, I wish I could be there to do it for her. But I’m stuck in here.

MARK’S FATHER [on home movie]:

Hey, where’s Mom? I can’t see her.

Mark’s father passed away in October 2022.

Mark has lost multiple state and federal appeals.

He is now making a long-shot appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

While Florida’s two-strikes law is one of the strictest, many states have laws that increase prison time for repeat offenders.

FEMALE INTERVIEWER:

Thank you, Mark.

MARK JONES:

Yes.

WRITTEN, PRODUCED & DIRECTED BY Ursula Liang

PRODUCED BY Tessa Travis

EDITED BY Eugene Yi

CO-PRODUCED & REPORTED BY Cary Aspinwall

CINEMATOGRAPHY Isaac Mead-Long

SENIOR PRODUCERS Carla Borrás Monika Navarro

ORIGINAL MUSIC Andrew Orkin

ASSISTANT EDITOR John Beder

GRAPHICS AND MOTION DESIGN Miles Alvord

ARCHIVAL PRODUCER Alethea Pace

OFFICE PRODUCTION ASSISTANT James Valdez

RESEARCHER Maurice Possley

PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Hilmari Gaines

SOUND RECORDIST Mike Garofalo

ONLINE EDITOR/COLORIST Jim Ferguson David Bigelow

SOUND MIX Jim Sullivan Christopher D. Anderson, C.A.S.

VOICE OF EUNICE HOPKINS Patricia Alvarado Núñez

ARCHIVAL MATERIAL Shutterstock The Jones family

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL ABC News Bay News 9 – Spectrum News The Florida Channel Florida Department of Corrections Florida PRR Families United Florida State Legislature N&T Electronics Seminole County Clerk’s Office Tampa Bay Times United States Military Academy West Point Wolfson Archive – Miami Dade College

SPECIAL THANKS Suejean Ahn Diane Garthwaite Matthew H. Liang Bibiana Murillo Brett Story Robert Jones Heather Gatheridge June Morgan Hailey Lingebach Tiffany Evans Eustesia McCree Dexter McCree Deborah Brennan Ren Ying Wu Abigail Ahn Yi William Still III Heather Gatheridge

FOR FIRELIGHT MEDIA

FILM MENTOR David Teague

SPECIAL INITIATIVES PRODUCER Nicole Docta

FINANCE & OPERATIONS COORDINATOR Allison Darko

OPERATIONS MANAGER Noel Davis

DIRECTOR OF FINANCE & OPERATIONS Rafiah Vitalis

LEGAL COUNSEL Fernando Ramirez

COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER Patricia Marte

COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR Justin Sherwood

SUPERVISING PRODUCER Julia Pontecorvo

SENIOR DIRECTOR ARTIST PROGRAMS Monika Navarro

EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Marcia Smith Stanley Nelson

FOR THE MARSHALL PROJECT

REPORTER Cary Aspinwall

ADDITIONAL REPORTING Weihua Li Dan Sullivan

SENIOR EDITOR, STORYTELLING Raghuram Vadarevu

SENIOR EDITOR Leslie Eaton

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Ruth Baldwin

MANAGING EDITOR Geraldine Sealey

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Susan Chira

ORIGINAL PRODUCTION FUNDING PROVIDED BY Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, FRONTLINE Journalism Fund with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler through the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen, committed to bridging cultural differences in our communities. Major support for FRONTLINE and for Two Strikes and Tutwiler from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

FOR FRONTLINE

DIRECTOR OF POST PRODUCTION Megan McGough Christian

SENIOR EDITOR Barry Clegg

EDITOR Brenna Verre

EDITOR Joey Mullin

EDITOR & POST PRODUCTION COORDINATOR Tim Meagher

ASSISTANT EDITORS Christine Giordano Alex LaGore

PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Stevie Jones

FOR GBH OUTPOST SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY Tim Mangini

INTERNS Joanna Hou

SERIES MUSIC Mason Daring Martin Brody

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Ellen O’Neill

OPERATIONS SPECIALIST Will Farrell

DIRECTOR OF IMPACT AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS Erika Howard

SENIOR DIGITAL WRITER Patrice Taddonio

PUBLICITY & AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT COORDINATOR Julia Heffernan

DIGITAL PRODUCER / EDITOR Tessa Maguire

MANAGER, PUBLIC RELATIONS AND COMMUNICATIONS Anne Husted

PODCAST PRODUCER Emily Pisacreta

ARCHIVES & RIGHTS MANAGER John Campopiano

BUSINESS ASSOCIATE Sean Gigliotti

FOR GBH LEGAL Eric Brass Suzy Carrington Jay Fialkov

SENIOR CONTRACTS MANAGER Gianna DeGiulio

BUSINESS MANAGER Sue Tufts

BUSINESS DIRECTOR Mary Sullivan

SENIOR DEVELOPER Anthony DeLorenzo

LEAD DESIGNER FOR DIGITAL Dan Nolan

FRONTLINE/COLUMBIA JOURNALISM SCHOOL FELLOWSHIPS TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW Kaela Malig

FRONTLINE/NEWMARK JOURNALISM SCHOOL AT CUNY FELLOWSHIP TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW James O’Donnell

FRONTLINE/MISSOURI SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM FELLOWSHIP MURRAY JOURNALISM FELLOW Kelsey Rightnowar

FRONTLINE/FIRELIGHT INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM FELLOWS Kevin Shaw Débora Souza Silva

ARCHIVAL PRODUCER Coral C. Salomón Bartolomei

EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Lauren Prestileo Callie T. Wiser

SENIOR DIGITAL PRODUCER / EDITOR Miles Alvord

SENIOR DOCUMENTARY EDITOR & PRODUCER Michelle Mizner

DIGITAL EDITOR Priyanka Boghani

STORY EDITOR & COORDINATING PRODUCER Katherine Griwert

POST COORDINATING PRODUCER Robin Parmelee

SENIOR EDITOR AT LARGE Louis Wiley Jr.

FOUNDER David Fanning

SPECIAL COUNSEL Dale Cohen

DIRECTOR OF AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT Maria Diokno

SENIOR PRODUCERS Dan Edge Frank Koughan

SENIOR PRODUCER, SPECIAL PROJECTS & INNOVATION Carla Borrás

SENIOR EDITOR & DIRECTOR, LOCAL JOURNALISM Erin Texeira

SENIOR SERIES PRODUCER Nina Chaudry

SENIOR EDITOR INVESTIGATIONS Lauren Ezell Kinlaw

MANAGING DIRECTOR Janice Hui

MANAGING EDITOR Andrew Metz

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Raney Aronson-Rath

A FRONTLINE Production with Noncompliant Films in association with Firelight Media & The Marshall Project

Copyright 2023 WGBH Educational Foundation, Firelight Media, Inc. & Noncompliant Films LLC All Rights Reserved

FRONTLINE is a production of GBH which is solely responsible for its content.

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.