|

|

|

by Peter Tyson Imagine taking a chain saw to a stalagmite. Imagine that stalagmite is not in a cave but on the seafloor a mile and a half down, and it is spewing toxic, scalding fluid, like a garden hose from hell. There is not the faintest glimmer of light, the surrounding seawater is a degree or two above freezing, and the pressure is enough to squeeze you into a stick figure faster than you can say boo. Luckily, you're not there. You're 7,000 feet up in a research ship bobbing lazily in the northeast Pacific. Your hands grip joysticks and your eyes are fixed on a video screen before you. There, on the monitor, you can see the "black smoker" chimney, as that stalagmite-like geyser is known. It is being filmed live from a video camera mounted on a remotely operated vehicle, which you're controlling from the other end of a long tether. You can also see the business end of the chain saw, which is also mounted on the robot. Your name, by the way, is Keith Shepherd, and you're about to try what no one has ever tried before: saw down a black smoker and have it lifted to the surface.

Brave new world In a way, this expedition had its genesis in 1977. That year, geologists made a series of astonishing discoveries during dives in a submersible to the seabed near the Galapagos Islands. They were looking for hydrothermal vents, cracks in the seafloor where seawater that has seeped into the ocean floor and come into contact with superheated rock rushes back up at scalding temperatures. Before this dive, scientists could only hypothesize that such vents existed, and that they were the place where new planetary crust was formed. The scientists found the vents, lending support to the notions of seafloor spreading, plate tectonics, and continental drift. But the researchers also stumbled upon something wholly unexpected: life forms living in the pitch dark,

Not long after that historic dive, other scientists came upon their first black smoker chimneys. They are called black smokers because they belch particle-laden, superheated water that looks like black smoke. The particles, composed primarily of sulfides, precipitate in a constant rain to form, directly below the belching smoke, an ever-growing chimney of stone. Black smokers look like miniature volcanoes in a constant state of eruption. Besides the particles, the eruptive material includes hydrogen sulfide, a chemical that heat-loving bacteria help convert into food for creatures higher up the food chain. Black smokers, which are a form of hydrothermal vent, make ideal homes for that strange community of life first seen in 1977.

Continue: An expedition is born The Mission | Life in the Abyss | The Last Frontier | Dispatches E-mail | Resources | Table of Contents | Abyss Home E-mail | TV Schedule | Web Schedule | Teachers Previous Sites | Search | Site Map | Shop | Printable page PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © |

||||||||||

Active "black smoker" chimney with tubeworms.

Active "black smoker" chimney with tubeworms.

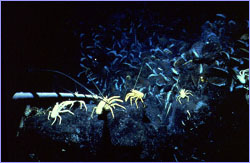

Mussels and crabs line a vent site near the

Galapagos.

Mussels and crabs line a vent site near the

Galapagos.

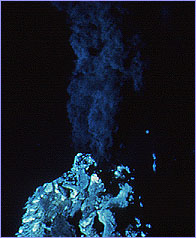

Black smoker erupting on the Juan de Fuca Ridge.

Black smoker erupting on the Juan de Fuca Ridge.