|

|

|

Search for a Vaccine part 2 | back to part 1 NOVA: Since everybody's genetic background is different and their immune systems react differently, and since there are a million variations of H.I.V. out there, is it possible that we won't be able to find a single overarching vaccine? Baltimore: We may never be able to make a vaccine. But I'm hopeful. We have to be optimistic at this point, because we don't have enough reason to be anything else. NOVA: What about the idea of a vaccine that changes the course of the disease rather than preventing it? Baltimore: I believe that whatever vaccine we come up with will change the course of the disease without preventing infection completely. In fact, all vaccines work that way. The polio vaccine doesn't prevent infection with polio; it prevents polio getting into the nervous system. So it prevents disease, not infection, and that's true of all vaccines. It means that people who get infected with H.I.V. may be infected in a lifelong way. We're infected with lots of viruses for our lives; they just don't cause the kind of problem that H.I.V. does. NOVA: But if you do get infected, and you don't get sick, the possibility is always there that it could pop up, right?

NOVA: How optimistic are you about being able to rescue the immune system in the early stages of H.I.V. infection? Baltimore: In the early stages, the immune system is not particularly devastated. So if we can suppress the virus I think the immune system will pop back. There is pretty good evidence now that it does come back and can be strong. It's people who have been infected for a long time whose immune system is really devastated. The question is: Can their immune systems be reconstituted to the point where they become immune-responsive to new pathogens, or where they can handle the environment around them? It's impressive how healthy people are who have been infected for a long time but in whom the virus is suppressed. Those people don't get opportunistic infections, they don't get a whole series of things you might worry about. So maybe enough immune response comes back to make them able to fight off the common problems.

Baltimore: You're now referring more to treatment of H.I.V. than prevention. We are in a position now where H.I.V. is a treatable disease. It's like many other diseases: not everybody responds well to the treatment, not everybody has their H.I.V. suppressed completely, not everybody can live with it for a very long time. That's no different than the treatment for a lot of other diseases. But enough people are suppressed in their virus load and are able to lead relatively complete lives that you have to say H.I.V. is a treatable disease. That's a major change over what was true just a couple of years ago. We've just got to get better at it. We've got to cut down the number of pills people have to take, make the regimen easier to follow, cut down the side effects, and design better and better drugs. But we have a platform now that we can build on, and it's only going to get better from here. NOVA: Where does the basic research on H.I.V. stand at this moment?

So the basic research effort on H.I.V. has been a very tough problem that has ramified into many areas of molecular biology, of immunology, and it's still going on. We still do not understand the details of most of H.I.V.'s very subtle genes. On the other hand, we've learned a tremendous amount along the way. We've learned a lot of new biology, and a lot of people are excited by it. The very best people in the country today are aware of the opportunity that H.I.V. provides to do really good biology. H.I.V. has definitely pushed the limits of science. It has pushed the limits of chemistry, of cell biology, of understanding transcriptional control, of understanding how genomes work, of integration of genes, just everything.

Baltimore: I don't know what's likely, but I can tell you what I hope for. I hope that we'll have a vaccine and that within what has to be measured in a decade or more we'll find a way to stimulate the immune system so that when people get infected, they suppress H.I.V. rather than allowing it to flourish. But for that to happen, I really think it will have to be based on some new thinking about viruses. Illustration: (7) Courtesy of Dr. José Assouline, University of Iowa College of Medicine. Search for a Vaccine | See HIV in Action | AIDS in Perspective The Virus Fighters | Fighting Back | Help/Resources Teacher's Guide | Transcript | Site Map | Surviving AIDS Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated October 2000 |

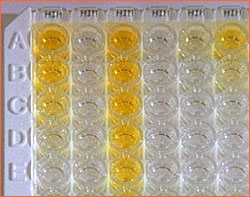

This viral load assay measures the amount of virus in

a patient's blood with a yellow indicator. The third

column from the left is a patient with acute HIV; the

fourth, long-term non-progressor Bob Massie.

This viral load assay measures the amount of virus in

a patient's blood with a yellow indicator. The third

column from the left is a patient with acute HIV; the

fourth, long-term non-progressor Bob Massie.

By studying the immune response of John Ceravsky, one

of the first HIV patients to volunteer to stop

therapy, scientists hope to find a cure for those

infected with HIV.

By studying the immune response of John Ceravsky, one

of the first HIV patients to volunteer to stop

therapy, scientists hope to find a cure for those

infected with HIV.

Combinations of antiviral drugs—the AIDS

cocktails—can prolong life for many patients.

Combinations of antiviral drugs—the AIDS

cocktails—can prolong life for many patients.

Finding a vaccine for HIV has pushed the limits of

chemistry, cell biology, and genetics. Finding a cure,

David Baltimore believes, will require truly

innovative thinking.

Finding a vaccine for HIV has pushed the limits of

chemistry, cell biology, and genetics. Finding a cure,

David Baltimore believes, will require truly

innovative thinking.