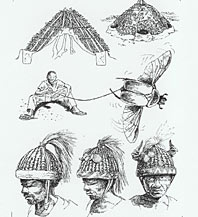

Jaglavak, Prince of Insects:

A Cameroon People's Alliance With an Ant

by Christian Seignobos

The

Mofu, who live in the Mandara Mountains of northern Cameroon,

have developed a rich lore about their insects and have a

particularly impressive entomological vocabulary. This may be

in part because insects are virtually the only other creatures

living on their jumble of boulders and terraces.

The Mofu eat certain insects, though this practice seems to

have been more widespread in the past than it is now. Insects

are also used in medicine and agriculture, serve as omens, and

are even the object of board games. And for the Mofu, certain

insects "speak" while others, like bees and mosquitoes, are

socially neutral.

The jaglavak

The Mofu are particularly interested in two types of insects,

those involved in the growth and conservation of grain

sorghum, their stable crop, and those ants or termites that

live in social groups. The Mofu relate these social insects to

their own politico-religious beliefs as well as to their

systems of kinship and social relations. Among ant species,

those of the Dorylus genus, a type of driver ant that

is known to the Mofu as jaglavak, hold a special place.

The Mofu associate the jaglavak with termites, which is

logical because jaglavak soldiers resemble those of certain

species of the termite order, Isoptera. The

Dorylus ants live in underground communities, sometimes

in large numbers, without building visible nests. Their

ferocity in attacking termites and the fact that no other

insects appear able to resist them have conferred upon the

jaglavak a position of eminence. Yet the jaglavak seemingly

avoids other insects that are "organized as it is," according

to the Mofu, including two species of termites that they know

as the mananeh (Microcerotermes solidus) and the

ndakkol (Trinervitermes trinervius), and

especially the gula ant (Megaponera sp.).

Chief of the massif

There are several "interpretations" of the jaglavak. In

relation to other insects, the jaglavak is defined by kinship

and relations of alliance or power. Some say the termite

mananeh is its "cousin"; others say the

mananeh is the "prince of the plain insects" and rival

of the jaglavak. The jaglavak's ndaw kuli (what the

Mofu call its "intimate friend"), who stands in for the head

of the family in sacrifices (kuli), is

singel gagazana, a red ant (Pheidole sp.), while

another ant, ndroa (Lepisiota sp.), is the

mananeh's "intimate friend." The jaglavak is considered

the chief of the entire massif, from Wazang to Meri (see map

at right), while other ants constitute "local chiefs." The

classification scheme is rough, and its composition varies by

region. One wonders, was it once more firmly fixed?

By virtue of an ancient alliance, the jaglavak are believed to

aid the Movo in times of trouble.

The Mofu see correlations between chiefs of the massifs and

chiefs of the animal realm. The panther and the Mofu chief are

one and the same; the chief commands the panthers. When a

panther is killed on a massif, by rule the skin goes to the

chief, who either keeps or disposes of the head and whiskers.

He is supposed to eat the eyes and give the liver to his sons.

The last act involved in the ritual burial of the massif

chiefs is the turning over of the mortuary bundle into the

grave, which is accomplished by pushing it while turning away

and imitating the panther's snarl.

In certain Mofu mountain ranges, and also among

the Jimi and the Gude, the crocodile was perceived as the chief of water-dwelling

animals. The death of a crocodile would be announced to the

chief as that of a relative would be, and people would cry

over it. When one was slaughtered, the chief would ritually

eat its tongue.

The jaglavak, for its part, held the role of "prince of

insects." In the past, Mofu mountain chiefs would closely

follow the jaglavak's movements and behavior to find omens. If

there was combat between the jaglavak and the ant

ndroa, for example, seers would interpret the

repercussions of this combat for the massif chiefdom. For the

Zumaya, the clan of the Douvangar chief, the jaglavak

furnished the

war stone, which would be found in its nest. In the absence of a

stone, in other massifs, such as that of the Meri people,

before combat people might put some jaglavak on a pointed

stone against which they would then rub their spearheads.

The "prince" and the Movo

The Mofu use the jaglavak to explain their own history, in

particular the case of the Movo. The jaglavak is supposed to

be the equivalent of the Movo people, who are now dispersed

among the Mofu. Long ago, the Movo possessed a powerful

chiefdom on the banks of the seasonal river Mayo Tsanaga, in

the foothills facing the principal point of entry into the

Mandara Mountains. This chiefdom was to give rise to the Gudur

chiefdom, installed higher up the mountain. In the 17th

century and the beginning of the 18th, the Movo dominated the

Mofu massifs and foothills and well beyond. Crushed by the

Wandala kingdom, from which they had originated, and then

dispersed by the Peuls, the Movo took refuge in the Mofu

massifs.

Today, the Movo are viewed as clans that inspire respect,

fear, indeed ostracism. Thus, the Movo are accused of sending

caterpillars into the sorghum crop and in the past have been

accused of sending locusts. And when a Movo individual is

buried, it is deemed necessary to spread ashes on the path

where the cadaver has passed, in order to prevent worms and

other granary predators from touching grain supplies.

The jaglavak is often designated as "the red insect,"

referring to the color that is the emblem of the Movo. And a

parallel can be seen in the fact that the jaglavak are

Dorylus ants, which move from place to place and do not

seem to have a territory, just like the Movo, who no longer

have their own chiefdoms. But like the jaglavak, the Movo are

feared for their power to harm. And by virtue of an ancient

alliance, the jaglavak are believed to aid the Movo in times

of trouble, including cleaning up their compounds by chasing

out undesirable insects, because the jaglavak is commonly

entrusted with chasing vermin out of infested dwellings.

Jaglavak to the rescue

The Mofu who sees his compound invaded by termites and ants

calls on the jaglavak for help. Dorylus colonies are

not easy to find. After identifying the nest or colony of

jaglavak on the move, the Mofu removes from the colony several

hundred to a thousand, or even more, Dorylus soldiers.

He puts them into a calabash or new clay pot, sometimes in

leaves of the large-leaved rock fig (Ficus abutilifolia). Among the Mofu, these leaves are used, for example, for

wrapping sacred objects, rain stones, and the meat of the

maray (the bull sacrificed at the feast of the massif).

They fear the jaglavak might kill them in the night, during

their sleep, by entering their nostrils.

When the Mofu carrying the ants arrive at the compound, people

salute the jaglavak in different ways, clicking their fingers

or striking the head of a hoe with a stone. The head of the

family declares, "Today we have a distinguished guest," and

then asks the jaglavak to chase out these harmful

insects—such as the momok (a generic term for

termites) and Trinervitermes ants from the straw

of the roof, and Macrotermes subhyalinus termites from

the sorghum stems protecting the walls—as well as

snakes. They ask the jaglavak, however, not to touch people

and to spare their animals, for they fear the jaglavak might

kill them in the night, during their sleep, by entering their

nostrils. Yet our informants were unable to cite any specific

instances of such an act of aggression.

The Mofu put the jaglavak on the ground within an ocher circle

from which extends a path, also traced in ocher, that leads

toward the area of the most badly infested house. The Mofu

admit that they do not see the jaglavak operate, but

they claim that two or three weeks later, the harmful insects

have disappeared, and the jaglavak as well, for they do not

remain in the compound, unlike the gula ant (which the

Kapsiki, another ethnic group of the Mandara Mountains, enlist

for the same job).

One might wonder about the conduct of the

Dorylus soldiers deprived of the mass effect of the

colony. Do they disperse an odor that causes other insects to

flee?

A waning tradition?

Jaglavak lore varies from massif to massif and depends on

which clans are in or out of power. Today, however, for the

Mofu who come down to the plains and go to work in urban

areas, everything concerning insects, including the role of

the jaglavak, is seen as belonging to the past.