|

|

Designing Clinical Trials

Part 2 |

Back to Part 1

Watching and waiting

Folkman was delighted that clinical trials had finally begun

for the antiangiogenesis drugs, and he was optimistic about

their long-term promise. But he knew exactly what to worry

about. Most central was the simple possibility that the

human body might metabolize the drug differently than the

mouse body, rendering it impotent. That's what he'd had in

mind when he'd quipped to Times reporter Gina Kolata

that if you were a mouse with cancer, he could take good

care of you.

The clinical trials, meanwhile, were out of his control. He

was just an intensely interested observer. So he worried

about how they were being run and how they were being

perceived. Someone might give the wrong doses and derail the

trials. Or people wouldn't truly understand the process,

especially with a new kind of drug like endostatin, which

needed time and patience. Some of these drugs—whether

those developed by his lab or by others—might fail, he

thought, perhaps leading some people to doubt his entire

premise. "It's the same as the Challenger space

shuttle," he told people. "Challenger crashed because

of a frozen O-ring. But that does not overturn Newton's

principles. Some drug failures are the result of bad

O-rings."

|

The clinical trials were run by others; all Dr.

Folkman could do was await the results.

The clinical trials were run by others; all Dr.

Folkman could do was await the results.

|

The clinical researchers worked hard to learn all they could

from the first patients. In all three centers, the patients

were tested almost incessantly with MRI scans, blood tests,

positron-emission topography (PET) scans, and a battery of

other diagnostic measures meant to watch for signs of damage

to their vital organs. It seemed to evoke the experience of

astronauts setting out on a dangerous test flight.

For some of the patients who found their way up Binney

Street in Boston to get their daily endostatin infusions,

the hardest part was the loneliness. Some patients had come

from as far across the country as Alaska, leaving family and

friends—all their support—behind. And when they

realized that the low doses were unlikely to cure them, some

gradually began to lose hope and concluded that the

isolation wasn't worth it. A man from Alaska gave up and

went home to be with his eight children, and face the dire

consequences of his cancer. Another patient missed her young

children so much that she, too, went home.

Meanwhile, the drug was showing zero toxicity in all the

Phase I trials. The doctors caring for these patients were

amazed that they saw none of the typical episodes of

vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, and loss of hair normally

experienced by patients in cancer drug trials. In fact, the

oncologists, who usually spent much of their time trying to

get their patients through the dreadful side effects of

chemotherapy, had very little to do. Their patients felt

fine, even wanting to put their clothes on and go home. Some

went on shopping trips, and a few even began talking about

taking vacations abroad. But some impatient cancer

researchers outside the trials took the seeming lack of

toxicity as a bad sign, an indication that the drug wasn't

working. "Toxicity is equal to efficacy in most oncologists'

minds," Roy Herbst, the oncologist who was leading the

endostatin trial in Houston, said in the early going.

"That's cancer. That's the way our drugs work." But this

drug was different. It wasn't chemotherapy. It wasn't

poison.

Drugs used in chemotherapy are toxic, but

antiangiogenic drugs work in a completely different

way.

Drugs used in chemotherapy are toxic, but

antiangiogenic drugs work in a completely different

way.

|

|

Signs of improvement

Little by little, as the doses of endostatin were increased

during the winter, a few reports began to leak out of the

three medical centers that a few patients were doing better.

In addition to the complete lack of toxicity, the doctors

were saying quietly to each other that in some patients the

tumors seemed to have stopped growing. The nurses knew it,

too, and the word had it in Boston that one man's

tumors—both his primary tumor and its

metastases—had begun to shrink. Even at tiny doses of

endostatin—in relative terms only one seventh the

doses that had been effective in mice—his metastases

were down 50 percent. Word from the clinic was that he was

feeling so good, despite being an end-stage cancer patient,

that he would come in for his daily injection and then head

off to work.

And he was not alone in showing progress. Another patient in

the Boston trial, described only as a 60-year-old woman from

Chicago fighting metastatic breast cancer, was also showing

signs of tumor shrinkage. Tests indicated that the interior

of her tumor was deteriorating, as if it were liquefying and

dying. She, too, was feeling far better than when she

arrived in Boston months earlier. But in July 2000 she

shocked the doctors by deciding to go home to Chicago,

needing to take care of pressing personal business. Daily

doses of endostatin were needed, but her doctors found no

way to arrange for her injections while she was out of town.

So there was real fear that an interruption in endostatin

treatments would free her tumor to regrow explosively. But

eleven days later, when she reported in again for treatments

at Dana-Farber, the relieved doctors found that her cancer

had not regrown. While visiting home, she had stopped in her

office to see fellow workers, who were amazed at how good

she looked and by her energy level and high spirits. She

obviously felt good, as did several other patients in the

trial, who reported much-improved quality of life.

|

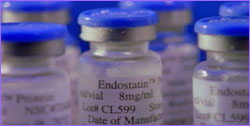

Endostatin appeared to help some patients in the

drug's first clinical trial.

Endostatin appeared to help some patients in the

drug's first clinical trial.

|

Such hints of success were not officially announced,

however, for fear of setting off a massive rush of patients

seeking a drug that was unproven, and in any event

unavailable. In April 2000, doctors and the Food and Drug

Administration decided it was better to wait and be sure,

allowing time for the drug-manufacturing process to be

scaled up before breaking any news. There wouldn't be much

solid evidence until the trial ended, and even bigger, more

convincing trials could begin.

It was at that point, in mid-March 2000, that the FDA asked

doctors at Dana-Farber to stop increasing doses until the

two other centers could catch up. The agency wanted everyone

to keep treating at 240 milligrams per kilogram of body

weight per day for a while to let the patient numbers build

up, while the debate continued over whether to escalate

higher, to 300, 400, or 500 milligrams per day. An intense

argument also erupted over whether—and what—to

report. Half of the experimenters wanted to present the data

on toxicity at the upcoming American Society of Clinical

Oncology meeting in mid-May, in New Orleans. Others in the

research group argued that even the data showing early signs

of efficacy in a few patients should be included. It was

evidence, albeit preliminary, that small, regular doses of

endostatin were associated with improvements, especially in

patients with the slowest-growing types of tumors. This

seemed to support Folkman's prediction that less-aggressive

cancers would be most sensitive to the drug.

In the spring of 2000, clinical trials began for

angiostatin, the other antiangiogenesis drug

developed in Dr. Folkman's lab at Children's

Hospital in Boston.

In the spring of 2000, clinical trials began for

angiostatin, the other antiangiogenesis drug

developed in Dr. Folkman's lab at Children's

Hospital in Boston.

|

|

Next up: angiostatin

As this was occurring, in spring 2000, trials began at

Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia for angiostatin,

the other antiangiogenesis drug developed in Folkman's lab.

The early results offered a surprise that had nothing to do

with cancer—a surprise to everyone but Folkman. One of

the first patients enrolled in the trial saw her

decades-long struggle with the skin disorder called

psoriasis suddenly resolve. Psoriasis is caused by abnormal

blood vessel growth in the skin, and it was one of the

ailments that Folkman had suggested might yield to

antiangiogenesis treatment. Although the results were

serendipitous—and seen only in one patient—the

discovery set off immediate interest in testing angiostatin

as a potential treatment for the very bothersome skin

condition. And it offered unexpected but welcome evidence

that antiangiogenesis treatment was offering value in

medical settings.

Excerpted with permission from

Dr. Folkman's War: Angiogenesis and the Struggle to

Defeat Cancer,

by Robert Cooke (Random House, 2001).

Newsday journalist Robert Cooke has been a science

writer for 35 years. For more information on clinical

trials—how they are designed, where they are

currently taking place, and more—see the National

Cancer Institute's Cancer Trials Web page at

http://www.cancer.gov/clinical_trials/.

Dr. Folkman Speaks

|

Cancer Caught on Video

Designing Clinical Trials

|

Accidental Discoveries

| How Cancer Grows

Help/Resources

|

Transcript

|

Site Map

|

Cancer Warrior Home

Editor's Picks

|

Previous Sites

|

Join Us/E-mail

|

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map

|

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated February 2001

|

|

|