|

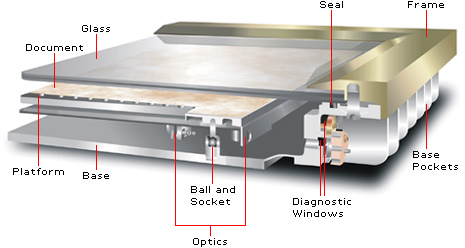

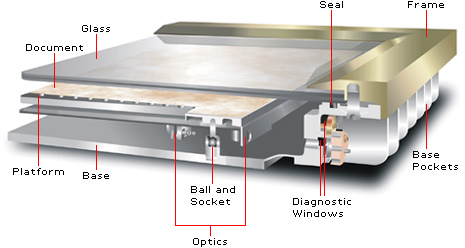

It took five years, over $5 million, and the expertise of hundreds

of people, but our country's oldest official documents—the

Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of

Rights—are now safely housed inside the most technologically

advanced picture frames in the world. Click on the cutaway

illustration below to explore the components of the Charters of

Freedom encasements.—Lexi Krock

|

Glass

The 3/8-inch-thick glass window on the surface of each

encasement has two jobs: to protect the documents inside and

to allow visitors the clearest possible view of them. Each

case's glass cover is a two-layer, heat-tempered sheet capable

of withstanding variations in barometric pressure and

temperature, and has a light-reflective coating that

eliminates glare from the lighting in the Rotunda of the

National Archives, where the Charters are on permanent

display.

|

|

Platform

A lightweight aluminum platform supports a layer of celluloid

paper and each Charters document. The documents are all

slightly different in size and none is perfectly square, so

each has its own specially machined aluminum platform. The

platform is perforated with about 4,000 holes, which provide

moisture transfer between the document and the environment

inside the case. The documents are held lightly onto the

platform with small plastic clips that viewers can see when

looking into the encasements.

|

|

Base

The builders of the encasements crafted their bases by

machining away most of the material from which they're made,

starting with blocks of aluminum about 40 inches square, three

inches thick, and weighing more than 500 pounds each. The end

result looks like a large cake pan. The base's inside surface

is anodized in jet black, which gives viewers the impression

that the Charters are floating in midair.

|

|

Document

Each of the Charters was handwritten with gall ink on

parchment. They are extremely fragile, even within their

cases. The documents sit on single sheets of archival paper

made of pure cellulose. The paper absorbs and releases

moisture as necessary, and it creates an opaque background for

the semi-translucent documents, which are otherwise difficult

to read. The environment around the document is maintained at

around 67°F with a humidity level of about 45 percent to

prevent the parchment from becoming brittle. The case is

filled with humidified argon, an inert gas that precludes

photo oxidation, the chief cause of fading.

|

|

Optics

An intricate optical system sits beneath the platform on which

the document rests. Its purpose is to facilitate diagnostic

tests of conditions inside the encasements. When special light

waves penetrate the case from one of two diagnostic windows on

its side, five mirrors reflect the beam and pass it out of the

second window, where a specially calibrated detector measures

its wavelength and intensity. These readings carry precise

information about the conditions inside the sealed case.

Conservators usually monitor oxygen and water levels, but they

can use the optical system to run many other tests as well.

|

|

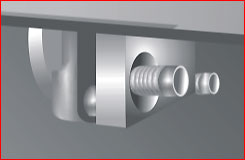

Ball and Socket

A ball-and-socket joint positioned between the platform where

the document rests and the bottom base of the encasement

serves to locate and secure the document platform in place.

This joint ensures that the document is completely immobile

even during moving.

|

|

Seal

Experts developed a special vacuum seal between the

encasement's base and front glass to ensure a nearly

impervious enclosure for the Charters. The seal is made of a

C-shaped piece of nickel and tin that deforms as the glass is

pulled tightly against the encasement's base, creating a

leak-proof barrier. Conservators' specifications for the ideal

environment inside the closed cases called for no more than

0.5 percent oxygen content—even after 100 years.

Laboratory tests indicated that the seal will outperform these

specifications.

|

|

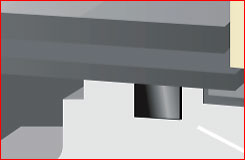

Diagnostic windows

Two small windows made of synthetic sapphire are set into the

wall of the case's base. They allow an absorption

spectrometer's signal—a beam of light from a cathode

lamp—to pass into and out of the encasement beneath the

document. Readings from the signal help conservators evaluate

whether the humidity and gas content inside is stable.

Scientists at the National Institute of Standards and

Technology chose synthetic sapphire for the windows' material

because it does not filter the infrared wavelengths needed to

conduct sensitive readings of the case's interior.

|

|

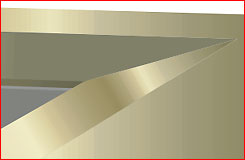

Frame

The titanium picture frame that surrounds each of the seven

encasements on display in the Rotunda of Washington's National

Archives is plated with a thin layer of gold. The frame was

designed to be as light as possible yet provide the strength

necessary to hold the glass in place on the base and form an

airtight seal. The frame also provides an aesthetic complement

to the grand décor of the Rotunda, an important

component of the Charters re-encasement project.

|

|

Pockets

To reduce the weight of the encasements and allow for easier

moving when necessary, waffle-like spaces were machined out of

the metal wherever possible, including on the bottom of the

base, seen here, and concealed from view between the bolts

beneath the case's outer frame.

|

|

|