|

|

|

Mind of a Codebreaker

Mind of a CodebreakerPart 2 | Back to Part 1 I thought of this imaginary German fellow with his wheels and his book of keys. He would open the book and find what wheels and settings he was supposed to use that day. He would set the rings on the wheels, put them into the machine, and the next thing he would have to do would be to choose a three-letter indicator for his first message of the day. So I began to think, how would he choose that indicator. He might just take it out of a book, or he might pluck it out of the air like ABC or whatever. Then I had the thought, suppose he was a lazy fellow, or in a tearing hurry, or had the wind up, or something or other and he were to leave the wheels untouched in the machine and bang the top down and look at the windows, see what letters were showing and just use them. Then another thought struck me. What about the rings? Would he set them for each of the three given wheels before he put them into the machine or would he set them afterwards? Then I had a flash of illumination. If he set them afterwards and, at the same time, simply chose the letters in the windows as the indicator for his first message, then the indicator would tend to be close to the ring setting of the day. He would, as it were, be sending it almost in clear.  If the intercept sites could send us the indicators of all

the Red messages they judged to be the first messages of the

day for the individual German operators, there was a

sporting chance that they would cluster around the ring

settings for the day and we might be able to narrow down the

17,576 possible ring settings to a manageable number, say 20

or 30, and simply test these one after the other in hope of

hitting on the right answer.

If the intercept sites could send us the indicators of all

the Red messages they judged to be the first messages of the

day for the individual German operators, there was a

sporting chance that they would cluster around the ring

settings for the day and we might be able to narrow down the

17,576 possible ring settings to a manageable number, say 20

or 30, and simply test these one after the other in hope of

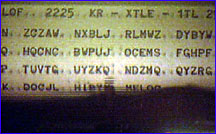

hitting on the right answer.The next day I went back to Hut 6 in a very excited state and told my colleagues of this idea. "Oh, brilliant," they all said. Welchman immediately arranged, very discreetly, for the first message indicators on the Red to be sent early each day to Hut 6. It was a simple matter to look for clusters. The idea, as my colleagues said, was a good one, and it was faithfully tested every day. Unfortunately, it never worked. Not that is until the unleashing of the German blitzkrieg in the West some two months later in May 1940. I wasn't there, but David Rees, who was on that particular night shift, noticed that among the first messages there were several whose indicators were very close together. So he tried the different possibilities on the different wheels and when I came in at 8 o'clock that morning, there was a little group of people around David who had broken the Red. He had got the right wheels and ring settings. Well it was a very exciting moment. Welchman drew me aside and he said: "Herivel, this will not be forgotten." The importance of the break that the Herivel Tip had allowed was not realized at the time. But the Red key would never be lost again. It became Bletchley Park's staple diet. It was used by countless Luftwaffe units and, because they needed to liaise closely with both the Army and the Navy in order to provide them with air support, its use gave a good overall insight into all the major German plans and operations. "From this point on it was broken daily, usually on the day in question and early in the day," recalled Peter Calvocoressi, one of the members of Hut 3. "Later in the war, I remember that we in Hut 3 used to get a bit tetchy if Hut 6 had not broken Red by breakfast time. Chinks in the Armor If German codemakers in the field had stuck unflinchingly to their instructions on how to encode messages, Polish and British codebreakers may never have succeeded in breaking the Enigma. Fortunately for the Allies, those German operators often typed in keys based on whatever came into their heads.  The first method of breaking the messages was the work of "the

Cilli Hunters" who relied on the tendency first identified by

[Polish mathematician and codebreaker Marian] Rejewski for

operators to choose keys that were easy to remember. "Just

occasionally you would get a chap who was rather fond of the

same letters," said Susan Wenham, one of the codebreakers

recruited by [codebreaker] Stuart Milner-Barry from Newnham

College, Cambridge. "It might be for some personal reason.

Perhaps one chap might use his girlfriend's initials for the

setting of the wheels or his own initials. Something like

that, you know silly little things. They weren't supposed to

do it but they did."

The first method of breaking the messages was the work of "the

Cilli Hunters" who relied on the tendency first identified by

[Polish mathematician and codebreaker Marian] Rejewski for

operators to choose keys that were easy to remember. "Just

occasionally you would get a chap who was rather fond of the

same letters," said Susan Wenham, one of the codebreakers

recruited by [codebreaker] Stuart Milner-Barry from Newnham

College, Cambridge. "It might be for some personal reason.

Perhaps one chap might use his girlfriend's initials for the

setting of the wheels or his own initials. Something like

that, you know silly little things. They weren't supposed to

do it but they did."Searching for Cillis, named after one of the operators' girlfriends whose name frequently appeared in the Enigma settings, became something of an art, said Mavis Lever. One was thinking all the time about the psychology of what it was like in the middle of the fighting when you were supposed to be encoding a message for your general and you had to put three or four letters in these little windows and in the heat of the battle you would put up your girlfriend's name or dirty German four-letter words. I am the world's expert on German dirty four-letter words! The other methods were the cribs and 'kisses,' messages that had been sent previously—perhaps on a lower-level radio net in a cipher that was already broken—and then turned up in the Enigma traffic, providing a crib for the message. This made it very easy for the codebreakers, though it was an infrequent occurrence. Most cribs were fairly short, although Mavis Lever remembered on occasion when there was a crib for a whole message.  The one snag with the Enigma of course is the fact that if

you press A, you can get every other letter but A. I picked

up this message and—one was so used to looking at

things and making instant decisions—I thought:

"Something's gone. What has this chap done? There is not a

single L in the message."

The one snag with the Enigma of course is the fact that if

you press A, you can get every other letter but A. I picked

up this message and—one was so used to looking at

things and making instant decisions—I thought:

"Something's gone. What has this chap done? There is not a

single L in the message."My chap had been told to send out a dummy message and he had just had a fag and pressed the last key of the middle row of his keyboard, the L. So that was the only letter that didn't come out. We had got the biggest crib we ever had, the encipherment was LLLL right through the message and that gave us the new wiring for the wheel. That's the sort of thing we were trained to do. Instinctively look for something that had gone wrong or someone who had done something silly and torn up the rule book. Continue: Turing's machines Crack the Ciphers | Send a Coded Message | A Simple Cipher Are Web Transactions Safe? | Mind of a Codebreaker | How the Enigma Works Resources | Teacher's Guide | Transcript | Site Map | Decoding Nazi Secrets Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |