|

|

|

Mind of a Codebreaker

Mind of a CodebreakerLed by the brilliant Alan Turing, inventor of the computer, the codebreakers of England's cipher-cracking organization, Bletchley Park, were mathematicians, crossword-puzzle fanatics, and other super-brains. For decades what these men and women did at "B.P.," and how they managed to break the Germans' seemingly impregnable Enigma encoding machine, was classified. Now, through works such as Station X: Decoding Nazi Secrets, by Michael Smith, from which the excerpts below were drawn, one can get a tantalizing glimpse of what went on inside the minds of these codebreakers, who were fully aware of how vital their mission was to the Allied effort. Tricks of the Trade Letter frequency, contact analysis, cribs: These are just some of the myriad weapons in the arsenal of Bletchley Park codebreakers. The first step in breaking any cipher is to try to find features which correspond to the original plain text. Whereas codes substitute groups of letters or figures for words, phrases or even complete concepts, ciphers replace every individual letter of every word. They therefore tend to reflect the characteristics of the language of the original text. This makes them vulnerable to studies of letter frequency; for example, the most common letters in English are E, T, A, O, and N. If a reasonable amount, or 'depth,' of English text enciphered in the same simple cipher were studied for "letter frequency," the letter that came up most often would represent E. The second most common letter would be T and so on. By working this out and filling in the letters, some will form obvious words with letters missing, allowing the codebreaker to fill in the gaps and recover those letters as well. Contact analysis, another basic weapon used by the codebreaker, takes this principle a step further. Some letters will appear frequently alongside each other. The most obvious example in the English language is TH as in 'the' or 'that'. By combining these two weapons the codebreaker could make a reasonable guess that where a single letter appeared repeatedly after the T which he had already recovered from letter frequency, the unknown letter was probably H, particularly if the next letter had already been recovered as E. In that case, he might conclude that the letter after the E was probably the start of a new word and so the process of building up the message would go on. Machine ciphers were developed to try to protect against these tell-tale frequencies and letter pairings, which is why the wheels of the Enigma machine were designed to move around one step after each 26 key strokes. By doing this, the Germans hoped to ensure that no original letter was ever represented by the same enciphered letter often enough to allow the codebreakers to build up sufficient depth to break the keys.  But it still left open a few chinks of light that would permit

the British codebreakers to attack it. They made the

assumption, correct far more often than not, that in the part

of the message being studied the right-hand wheel would not

have had the opportunity to move the middle wheel on a notch.

This reduced the odds to a more manageable proportion. They

were shortened still further by the Enigma machine's great

drawback. No letter could ever be represented by itself.

But it still left open a few chinks of light that would permit

the British codebreakers to attack it. They made the

assumption, correct far more often than not, that in the part

of the message being studied the right-hand wheel would not

have had the opportunity to move the middle wheel on a notch.

This reduced the odds to a more manageable proportion. They

were shortened still further by the Enigma machine's great

drawback. No letter could ever be represented by itself.This fact was of great assistance in using cribs, pieces of plain text that were thought likely to appear in an Enigma message. This might be because it was in a common pro forma, or because there was an obvious word or phrase it was expected to contain. Sometimes it was even possible to predict that a message passed at a lower level, on a system that had already been broken, would be repeated on a radio link using the Enigma cipher. If the two identical messages could be matched up, in what was known as a 'kiss,' it would provide an easy method of breaking the key settings. The Germans, with their liking for order, were particularly prone to providing the British with potential cribs. The same words were frequently used at the start of messages to give the address of the recipient, a popular opening being An die Gruppe (To the group). Later in the war, there were a number of lazy operators in underemployed backwaters whose situation reports regularly read simply: Keine besondere Ereignisse, literally "no special occurrences," perhaps better translated as "nothing to report."  Most cribs could appear at any point in the message. Even

Keine besondere Ereignisse was likely to be preceded or

followed by some piece of routine information. But the fact

that none of the letters in the crib could ever be matched up

with the same letter in the enciphered message made it much

easier to find out where they fitted.

Most cribs could appear at any point in the message. Even

Keine besondere Ereignisse was likely to be preceded or

followed by some piece of routine information. But the fact

that none of the letters in the crib could ever be matched up

with the same letter in the enciphered message made it much

easier to find out where they fitted.If we take Keine besondere Ereignisse as our crib and place it above an enciphered message, divided into the five-letter groups in which they would normally be sent by the German Army or Air Force operators, it is easy to see that the number of places it would fit are limited by the fact that no letter can be enciphered as itself.

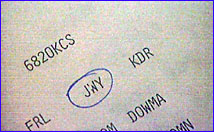

KEIN EBESO NDERE EREIG NISSE

GEGOH JYDPO MQNJC OSGAH LEIHY SOPJS MIUKKMoving the message just one place to the left or right would have one of the first two Es of Ereignisse enciphered as itself, an obvious impossibility on the Enigma machine. Moving it even further to the left or right only produces more duplicated letters. In this particular case, and it was only rarely ever that easy, this is in fact the only place in which the crib could fit. Mavis Lever, a member of Knox's team, described the codebreaking process. If you think of it as a sort of crossword technique of filling in what it might be. I don't want to give the impression that it was all easy. You did have inspired guesses. But then you would also have to spend a lot of time, sometimes you would have to spend the whole night, assuming every position that there could be on the three different wheels. You would have to work at it very hard and after you had done it for a few hours you wondered, you know, whether you would see anything when it was before your eyes because you were so snarled up in it. But then of course, the magic moment comes when it really works and there it all is, the Italian, or the German, or whatever it is. It just feels marvellous, absolutely marvellous. I don't think that there is anything one could compare to it. There is nothing like seeing a code broken, that is really the absolute tops. The Herivel Tip John Herival was a 21-year-old Cambridge mathematician hell-bent on breaking Red, one of the main Enigma ciphers used by the Germans in World War II. Combining mathematical skills with what Smith describes as "Alice in Wonderland-type thought processes," Herivel got his wish late one evening.  [Herivel] had arrived at the Park at the end of January 1940

and was taken to the mansion where a naval officer made him

sign the Official Secrets Act. "Then he gave me the address of

my digs, which were just down the road from the Park and also

he told me where to go, to Hut 6 [one of many units within

B.P.], which of course had been effectively founded by

[codebreaker Gordon] Welchman. I had been recruited by

Welchman and I was going to work in his show."

[Herivel] had arrived at the Park at the end of January 1940

and was taken to the mansion where a naval officer made him

sign the Official Secrets Act. "Then he gave me the address of

my digs, which were just down the road from the Park and also

he told me where to go, to Hut 6 [one of many units within

B.P.], which of course had been effectively founded by

[codebreaker Gordon] Welchman. I had been recruited by

Welchman and I was going to work in his show."Unlike [codebreaker Dilly] Knox, Welchman believed in giving the new recruits like John Herivel some training on the Enigma machine. There were two people that instructed me in the mysteries of Enigma and the method which they had been using to solve it from time to time. They were Alan Turing and Tony Kendrick. I don't know how many hours they devoted to us but it didn't all happen in one day. I do remember that when I came to Hut 6, we were doing very badly in breaking into the Red code. Every evening, when I went back to my digs and when I'd had my supper, I would sit down in front of the fire and put my feet up and think of some method of breaking into the Red code. I had this very strong feeling: "We've got to find a way into the Red again." I kept thinking about this every evening and I was very young and very confident and I said I'm going to find some way to break into it. But after about two weeks I hadn't made any progress at all. Then, just like Knox asking which way round does the clock go [when people answered clockwise, he replied "Not if you're the clock"], Herivel examined the problem from a totally different perspective. Up until the middle of February, I had simply been thinking in terms of the encoded messages which were received daily and which came to Hut 6. Then one evening, I remember vividly suddenly finding myself thinking about the other end of the story, the German operators, what they were doing and inevitably then I thought of them starting off the day. Continue: the imaginary German fellow with his wheels and his book of keys Crack the Ciphers | Send a Coded Message | A Simple Cipher Are Web Transactions Safe? | Mind of a Codebreaker | How the Enigma Works Resources | Teacher's Guide | Transcript | Site Map | Decoding Nazi Secrets Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |