|

|

|

by Peter Tyson Glittering stars in the night sky aside, scientists have long known that there are diamonds in the heavens. In 1981, for example, when Smithsonian researchers tried to cut through a large iron meteorite that had crash-landed in the Allen Hills of Antarctica, the sawteeth on their blade got all chewed up. Subsequent x-rays showed that the stone was riddled with microscopic diamonds, the hardest substance known. The scientists theorized that the meteorite's diamonds were born during a cataclysmic collision out in the asteroid belt.

Still other diamonds are apparently created during the fiery instant when meteors and meteorites slam into Earth. In the 1960s, scientists discovered more microscopic diamonds in the remains of the vast Canyon Diablo meteorite, which formed Meteor Crater in Arizona. The diamonds are sand-grain-sized, only hundredths of an inch across. Other crater-related diamonds are larger. In the 35-mile-wide Popigari crater in Siberia, the result of a huge impact 35 million years ago, Russian researchers unearthed polycrystalline diamond clusters reaching nearly half an inch across. Many of these impact-spawned diamonds bear the cubic structure of ordinary, Earth-grown diamonds. But analysts studying the Canyon Diablo diamonds found that up to a third of them bore a hexagonal atomic structure never before seen in diamond. Mineralogists named the new hexagonal variant of diamond lonsdaleite after the British mineralogist Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, who helped advance the study of natural diamond crystals.

Whatever the origin of meteorite diamonds, some scientists believe they have found evidence that the colossal cloud of dust thought to be thrown up into the atmosphere in the wake of such impacts may spread newly formed diamond dust all around the world. In 1991, Canadian geologists David B. Carlisle and Dennis R. Braman reported finding Lilliputian diamonds embedded in a layer of sediment 65 million years old - right at the time when many scientists believe a giant meteor slammed into Earth and precipitated the extinction of the dinosaurs. Can these miniature diamonds, which are so fine-grained that the researchers deem them the result of a collision, serve as an indicator of this ancient catastrophe, much as the famous iridium layer has done? Scientists won't be able to say without further study, but the idea holds promise. (In the 1998 book The Nature of Diamonds, the geologist George Harlow and two Russian colleagues wrote simply, "This subject is very new, and many exciting discoveries have yet to be announced.")

Outer space may also be the birthplace of the mysterious black diamonds known as carbonados. From the Portuguese word for burned or carbonized, carbonados were first found in Brazil in the 1800s and have since turned up elsewhere, most notably in central Africa. Unlike the clear diamonds of engagement rings, which are single crystals, black diamond consists of aggregations of individual crystals, which lend the gem its dark color. The largest diamond ever found was a carbonado from Brazil; named Sergio, the stone weighed 3,167 carats. (One carat equals one-fifth of a gram.) The origins of carbonados have long baffled scientists. Black diamonds don't adhere to the rules of diamond mineralogy, and they don't occur in the usual places where clear diamonds are found. Even so, scientists initially believed they must have been fashioned in the same conditions under which clear diamonds are thought to form. That is, they were crafted deep within the Earth, 100 to 300 miles down, when intense heat and pressure transformed carbon into diamonds, which volcanic eruptions then lofted to the surface. But that theory suffered a blow when scientists examined the carbon isotopes of black diamonds. (Isotopes are species of a chemical element that reside in the same place on the periodic table but have different atomic weights and physical properties.) Unlike clear diamonds, black diamonds feature ratios of the two most common carbon isotopes in the Earth's crust—carbon-12 and carbon-13—that characterize surface carbons rather than those found in the Earth's depths. Continue: A new theory of carbonado formation The Science Behind the Sparkle | Diamonds in the Sky A Primer of Gemstones | See Inside a Diamond Resources | Transcript | Site Map | Diamond Deception Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

Scientists have long suspected that at least some

diamonds found on Earth hail from the heavens.

Scientists have long suspected that at least some

diamonds found on Earth hail from the heavens.

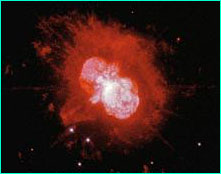

Can dying stars known as red giants spawn diamonds?

Some scientists think so.

Can dying stars known as red giants spawn diamonds?

Some scientists think so.

Microscopic diamonds appear to have formed in the

fiery instant when the meteor that created Arizona's

Canyon Diablo struck the Earth.

Microscopic diamonds appear to have formed in the

fiery instant when the meteor that created Arizona's

Canyon Diablo struck the Earth.

The black diamonds known as carbonados got their name

for their carbonized, or burnt, look.

The black diamonds known as carbonados got their name

for their carbonized, or burnt, look.