|

|

|

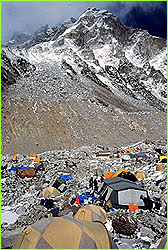

Going Higher: Up to Camp II by Liesl Clark  At 4:30 a.m. a low deep hiss hits the senses before cognition

arrives. It's a sound like no other that seeps into your

dreams until you awaken to reality; you're at Everest Base

Camp. Someone is already in the kitchen tent heating up water

for morning tea. Throughout the day the hiss of the kerosene

stove will continue—it's our lifeline of fuel and fire

to heat water and food. Without it, we'd be unable to survive

up here at 17,600 feet. Ice crystals cling to the roofs of our

tents, the remains of frozen breaths from a long night of

sleep in zero-degree temperatures.

At 4:30 a.m. a low deep hiss hits the senses before cognition

arrives. It's a sound like no other that seeps into your

dreams until you awaken to reality; you're at Everest Base

Camp. Someone is already in the kitchen tent heating up water

for morning tea. Throughout the day the hiss of the kerosene

stove will continue—it's our lifeline of fuel and fire

to heat water and food. Without it, we'd be unable to survive

up here at 17,600 feet. Ice crystals cling to the roofs of our

tents, the remains of frozen breaths from a long night of

sleep in zero-degree temperatures. Today David Breashears, Jangbu Sherpa, Pete Athans (our climbing digital cameraman), and our team's three climbing Sherpas are all heading up the Icefall to Camp I, and then on to Camp II. Ed Viesturs and David Carter are at Camp II, having spent several nights up there already, for acclimatization.  I throw on several layers of clothing before unzipping the

tent door to crawl out into the early morning freeze. There's

no movement outside, the stars are out, and the peaks stand

silently, waiting for the first rays of sun to hit them. An

early morning stumble to the kitchen tent demands a concerted

effort in coordination, to avoid tripping over the many shaped

stones that layer the ice of the glacier.

I throw on several layers of clothing before unzipping the

tent door to crawl out into the early morning freeze. There's

no movement outside, the stars are out, and the peaks stand

silently, waiting for the first rays of sun to hit them. An

early morning stumble to the kitchen tent demands a concerted

effort in coordination, to avoid tripping over the many shaped

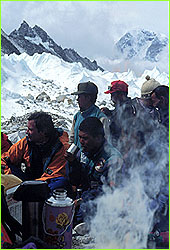

stones that layer the ice of the glacier. You have to duck down to enter through the hanging tarp "door" of the kitchen tent, and a cup of milk tea is handed to you the moment you step inside. David, Pete, and Jangbu cradle warm cups in their hands as they sit on the stone seats that make up the kitchen tent's walls. A blue tarp acts as the ceiling for the kitchen's stone structure, which is lined on one side with cans of vegetables, sugar, and powdered milk. In the center of the tent is a stone table where the two kerosene stoves hiss all day long.  Why do the climbers have to leave so early for a trip through

the Icefall? "You want to get in there before the sun hits,"

explains David. "It not only gets so hot up there you can

barely move, but with the sun's heat there's the perception

that the Icefall becomes less stable and large pieces of

glacial ice can come tumbling down on top of you." Twice

already, ladders have come down on the route through the

Icefall, putting a stop to all traffic between Base Camp and

Camp I. "Generally when that happens, it means the ice that

the bottom ladder was set on just gave way," interjects Pete

Athans. "And, it just means time for the ladders to be re-set

again."

Why do the climbers have to leave so early for a trip through

the Icefall? "You want to get in there before the sun hits,"

explains David. "It not only gets so hot up there you can

barely move, but with the sun's heat there's the perception

that the Icefall becomes less stable and large pieces of

glacial ice can come tumbling down on top of you." Twice

already, ladders have come down on the route through the

Icefall, putting a stop to all traffic between Base Camp and

Camp I. "Generally when that happens, it means the ice that

the bottom ladder was set on just gave way," interjects Pete

Athans. "And, it just means time for the ladders to be re-set

again."Continue: The Magic Hour Lost on Everest | High Exposure | Climb | History & Culture | Earth, Wind, & Ice E-mail | Previous Expeditions | Resources | Site Map | Everest Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |