|

|

|

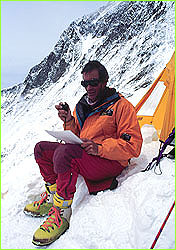

Thin Air Page 2 | Back to Page 1 A Day in the Life at Camp III 7:30 am—The radio crackles with an unintelligible voice. I grab the small walkie-talkie thrown into a dark corner of my tent: "Is that Camp III? Please come again." "Camp III to Base Camp, over." "Good morning David, how are you?" "Pete and I had a very fitful night. We're paying the price for climbing to Camp III and then not descending to Camp II for the night. Because we've just come up to Camp III and have slept here, Pete had an altitude headache last  night and my vision is blurred this morning. That would be the

case for two climbers that came up and occupied Camp III on

their first visit. It breaks the cardinal rule of high

altitude mountaineering, which is 'climb high, sleep low.'

Most people come up here for a visit, return to Camp II and

then come up to spend the night, but Pete and I figured we

have enough experience and we'll just increase our schedule a

little bit. There's no danger to us and no danger to our

climbing on Everest. We just wanted to be up here—it was

beautiful—so we stayed."

night and my vision is blurred this morning. That would be the

case for two climbers that came up and occupied Camp III on

their first visit. It breaks the cardinal rule of high

altitude mountaineering, which is 'climb high, sleep low.'

Most people come up here for a visit, return to Camp II and

then come up to spend the night, but Pete and I figured we

have enough experience and we'll just increase our schedule a

little bit. There's no danger to us and no danger to our

climbing on Everest. We just wanted to be up here—it was

beautiful—so we stayed."David continues, "Three things are at work here: the altitude, dehydration, and particularly in my case, I take my glasses off a lot to film, and I can get a minor headache from that, which has nothing to do with the altitude. We got up here yesterday, dehydrated, extremely tired and had to spend two hours preparing our tent platform. Our heart rates were very high, we finally got the tent up and literally collapsed into the tent, lay horizontal for at least an hour before we summoned up the energy to collect snow and light the stove. We didn't rehydrate enough last night and we were both very, very thirsty." 8:00 am—David and Pete wait for the sun to hit the tent. Hoar frost has taken over the ceiling of the tent and they wait for it to melt and evaporate. The trick is to refrain from rustling the walls or ceiling of the tent so as to  avoid being rained on by a shower of frozen or half-melted

ice. They light the small camp stove in the vestibule of their

tent, and then lay back down for another 45 minutes, watching

the ceiling drip as the ice in the stove slowly melts into

drinkable liquid. They fill their water bottles, fill the

stove again with ice and snow, and crawl out of the tent.

avoid being rained on by a shower of frozen or half-melted

ice. They light the small camp stove in the vestibule of their

tent, and then lay back down for another 45 minutes, watching

the ceiling drip as the ice in the stove slowly melts into

drinkable liquid. They fill their water bottles, fill the

stove again with ice and snow, and crawl out of the tent.The morning hours at Camp III are remarkably quiet. There sky is overcast with a diffuse light, and the air is windless, as it was all through the preceding night. Looking up to the peak, it looks like a perfect summit day; there's not a breath of wind anywhere on the mountain. David remarks over the radio, "You could light a candle where I'm standing. This is very rare indeed, especially since yesterday it was incredibly windy up high." Sherpas show up and begin digging another tent platform nearby, as David and Pete continue drinking tea and hot chocolate to stay hydrated. 12:00 noon—We get another status report by radio from David: "Today we feel good. We took it easy this morning. We're drinking a lot and we're going to have lunch shortly. We won't go more than 25-30 feet from camp today. Now we're  going to have lunch, then we'll do the high altitude

neuro-behavioral tests, go and work on some tent platforms for

Guy Cotter's team, get some exercise up here, and shoot some

scenics."

going to have lunch, then we'll do the high altitude

neuro-behavioral tests, go and work on some tent platforms for

Guy Cotter's team, get some exercise up here, and shoot some

scenics."1:00 pm—We get a radio call from Doug Rovira, a doctor climbing with the Canadian team, who reports that two of our climbing Sherpas (both named Dorje) are sick. "Older Dorje has bacterial dysentery. He threw up antibiotic last night. Young Dorje has fevers and chills and a sore throat. He's on antibiotics. Both Dorjes look pretty green. Jangbu and Kami, on the other hand, look like a million bucks." We're a small expedition with only four climbing Sherpas, unlike the other expeditions here on Everest, which have anywhere from seven to 20 Sherpas assisting them and carrying loads on the mountain. When we check in with David and Pete on a decision about whether the two Dorjes should come back down to Base Camp, David replies, "They almost have all the loads to the Col (Camp IV) and we have at least another eight days before we head back up so we are not that concerned about it. We are more concerned with them pressing on when they shouldn't, and burning out early. As long as they  go down, they will recover. If a Sherpa feels great a day or

two after taking medicine at Advance Base Camp and he wants to

go up, that's his decision but we will not prevail upon them

to carry loads when they don't feel well."

go down, they will recover. If a Sherpa feels great a day or

two after taking medicine at Advance Base Camp and he wants to

go up, that's his decision but we will not prevail upon them

to carry loads when they don't feel well."7:00 pm—I place my last radio call of the day to David and Pete to say goodnight. David, still working through the lassitude of the day, has a final comment, "If the truth be known, my trip from Camp II to Camp III yesterday was about the hardest five hours I've ever spent on this mountain. When I got to camp, the last thing I wanted to do was spend two hours on a tent platform. As long as Pete was gonna kick and shovel snow around, I certainly couldn't just sit around on my butt and be the lazy boy. So I did, and now, thank god, I feel much better. Because if I was going to feel that bad all night I don't know what I was going to do about climbing up there—that tiny little bump way up there called the summit. But it's part of the ritual, part of the game. Everybody gets one bad day on this mountain when they are up here and I've had mine and it's usually going to Camp III."" A Case of Pulmonary Edema Peter Weeks, a New Zealander attempting Everest this year has come down with pulmonary edema while climbing the mountain. "I just had a real lack of energy,  just couldn't move quickly, could only move a few paces at a

time and had to stop and breathe," says Weeks. "Even downhill

easy parts were very strenuous. I wasn't aware that it was

altitude-related, I just thought I was very tired and

exhausted. When I was diagnosed with pulmonary edema, it was a

bit of a surprise. In my lungs I felt a bit of crackling, sort

of gurgling, something going on there."

just couldn't move quickly, could only move a few paces at a

time and had to stop and breathe," says Weeks. "Even downhill

easy parts were very strenuous. I wasn't aware that it was

altitude-related, I just thought I was very tired and

exhausted. When I was diagnosed with pulmonary edema, it was a

bit of a surprise. In my lungs I felt a bit of crackling, sort

of gurgling, something going on there."His expedition's doctor, David Fernley, put him into a Gamow bag—a pressurized nylon enclosure—and pressurized him to a lower altitude for an hour and a half. Peter recalled the experience: "I was put in there, zipped up, and then the pressure increased and I found it easier to breathe, which was great and relaxing, but towards the end of the session it got a bit claustrophobic and I was very happy to get out of it." Dr. Fernley noted that Week's pulse oximeter reading was 45%, so Fernley put him on oxygen at a flow rate of 1.5 liters per minute. Continue Lost on Everest | High Exposure | Climb | History & Culture | Earth, Wind, & Ice E-mail | Previous Expeditions | Resources | Site Map | Everest Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |