|

|

|

The news that shocked the world: We have only about

twice as many genes as your average fruit fly.

The news that shocked the world: We have only about

twice as many genes as your average fruit fly.

|

Nature vs Nurture Revisited

by Kevin Davies

The most shocking surprise that emerged from the full

sequence of the human genome earlier this year is that we

are the proud owners of a paltry 30,000 genes -- barely

twice the number of a fruit fly.

After a decade of hype surrounding the Human Genome Project,

punctuated at regular intervals by gaudy headlines

proclaiming the discovery of genes for killer diseases and

complex traits, this unexpected result led some journalists

to a stunning conclusion. The seesaw struggle between our

genes -- nature -- and the environment -- nurture -- had

swung sharply in favor of nurture. "We simply do not have

enough genes for this idea of biological determinism to be

right," asserted Craig Venter, president of Celera Genomics,

one of the two teams that cracked the human genome last

February. [For a conversation with Venter, see

Meet the Decoders.]

Indeed, Venter has wasted little time in playing down the

importance of the genes he has catalogued. He cites the

example of colon cancer, which is often associated with a

defective "colon cancer" gene. Even though some patients

carry this mutated gene in every cell, the cancer only

occurs in the colon because it is triggered by toxins

secreted by bacteria in the gut. Cancer, argues Venter, is

an environmental disease. Strong support for this viewpoint

appeared last year in the

New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers in

Scandinavia studying 45,000 pairs of twins concluded

that cancer is largely caused by environmental rather than

inherited factors, a surprising conclusion after a decade of

headlines touting the discovery of the "breast cancer gene,"

the "colon cancer gene," and many more.

Notwithstanding the valuable discovery of BRCA1,

the "breast cancer gene," researchers insist the

causes of cancer lie more with nurture than with

nature.

Notwithstanding the valuable discovery of BRCA1,

the "breast cancer gene," researchers insist the

causes of cancer lie more with nurture than with

nature.

|

|

But can the role of heredity really be dismissed so easily?

In fact, the meager tally of human genes is not the affront

to our species' self-esteem as it first appears. More genes

will undoubtedly come to light over the next year or two as

researchers stitch together the final pieces of the human

genome. More importantly, human genes give rise to many

related proteins, each potentially capable of performing a

different function in our bodies. A conservative estimate is

that 30,000 human genes produce ten times as many proteins

in the human body, and figuring out what these proteins do

will be a challenge for a century or more. "This is just

halftime for genetics," says Eric Lander, a leading member

of the public genome project, alluding to decades of work

ahead to unravel the function of all the proteins in the

body. [For a conversation with Lander, see

Meet the Decoders.]

Our snips, ourselves

The key to ultimately defining the respective roles of genes

and environment lies with 'snips' -- genespeak for the sites

littered throughout our DNA that frequently vary between

unrelated people. About three million differences exist in

the genomes of any two unrelated people, but of these only

about 10,000 or so are likely to have any functional

consequences.

|

Fingering the flaws in their patients' genetic code

will enable doctors of the near future to better

prepare those individuals with high risk for certain

diseases.

Fingering the flaws in their patients' genetic code

will enable doctors of the near future to better

prepare those individuals with high risk for certain

diseases.

|

Scientists have already linked some of these specific DNA

variations with increased risk of common diseases and

conditions, including cancer, asthma, diabetes,

hypertension, and Alzheimer's. Other snips affect the way

people react toward certain drugs. Everyone carries between

five and 50 genetic glitches that might predispose that

person to a serious physical or mental illness. Identifying

these flaws will enable doctors to predict individual

disease risks, recommend suitable lifestyle regimens, and

prescribe the safest and most effective drugs.

But divining DNA variations to uncover health risks will

increasingly threaten our ability to land and hold jobs,

secure insurance, and keep our personal genetic profiles

private. "We're all ultimately unemployable and

uninsurable," warns New York Representative Louise

Slaughter, co-author of a new genetic privacy bill in

Congress, "even the president of a health insurance

company!" Without laws prohibiting genetic discrimination,

she says, society may soon begin penalizing people with

'bad' genes. Even though 22 states have passed genetic

privacy laws, Slaughter believes the confidentiality of your

genetic code should not depend on your zip code. Francis

Collins, director of the public genome project, says "We

don't get to pick our genes, so our genes shouldn't be used

against us." [For a conversation with Collins, see

Meet the Decoders.]

Ever since the early days of genome sequencing,

scientists have searched for elusive genetic clues

to human behavior.

Ever since the early days of genome sequencing,

scientists have searched for elusive genetic clues

to human behavior.

|

|

Becoming us

While the next few years will undoubtedly see major progress

in rooting out genetic factors that influence our likelihood

of contracting common diseases, what about the role that

genes play in shaping human behavior and personality?

Despite the media hype following recent claims for the

discovery of genes controlling addiction, shyness, thrill

seeking, and most controversially, sexual orientation, in

reality these genes have provided little more than

tantalizing clues to these traits. No one has identified (or

even claimed to have identified) a "gay gene," and the first

few genes associated with other personality traits appear to

have only a minor effect. However, with the full genome

sequence now accessible over the Internet, scientists hope

to pin down many more genes that code for various aspects of

human behavior.

Yet is it realistic to believe that single genes can have a

major impact on behavior? Much attention is currently

focused on the genes that code for proteins involved in the

transmission of electrical signals in the brain. If drugs

such as the antidepressant Prozac work by altering the

activity of neurotransmitters (brain chemicals that convey

messages between nerve cells), it is plausible that

inherited variations in the proteins that produce those

chemicals could exert a dramatic effect on an individual's

mood and temperament. But even the most diehard geneticists

acknowledge that the environment plays a major role in

shaping our behavior, temperament, and intelligence.

With so much attention on explaining behavior in terms

either of nature or nurture, scientists at the

University of California, San Francisco recently described a

fascinating example of how heredity and environment can

interact. Perfect pitch is the ability to recognize the

absolute pitch of a musical tone without any reference note.

People with perfect pitch often have relatives with the same

gift, and recent studies show that perfect pitch is a highly

inherited trait, quite possibly the result of a single gene.

But the studies also demonstrate a requirement for early

musical training (before age six) in order to manifest

perfect pitch. Time will tell whether there is a "perfect

pitch" gene, but it seems reasonable to think that many

personality and behavioral traits will not be exclusively

the province of nature or nurture, but rather an

inextricable combination of both.

|

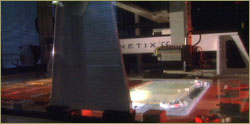

Highly sophisticated technology, like this

gene-sequencing machine at Celera Genomics, is

helping to spur advances in molecular medicine.

Highly sophisticated technology, like this

gene-sequencing machine at Celera Genomics, is

helping to spur advances in molecular medicine.

|

Gene genies

Regardless of how many genes are ultimately linked to

disease risk and human behavior, one thing is certain: The

technology to detect and possibly select genes for future

generations is rapidly improving.

In the near future, DNA chips will exist that can detect

thousands of the most significant variations in our DNA. A

decade or two from now, parents of newborn babies may leave

the hospital with a full genome analysis of their offspring

that reveals hundreds of disease-related risk factors and

susceptibilities. And doctors will be able to screen for

more and more traits using in vitro fertilization techniques

such as preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). Doctors

demonstrated the power of PGD last year when the Jack and

Lisa Nash family of Englewood, Colorado selected an embryo

that not only lacked the gene for a fatal genetic disease,

Fanconi anemia, but also provided a bone marrow match for

their dying daughter.

Thus, while Venter is undoubtedly right when he proclaims

that "humans are not hardwired," increasingly we will be

able to fiddle with our genetic wiring such that, in the

complex balance achieved by nature and nurture,

nature gets a little boost.

Dr. Kevin Davies

Dr. Kevin Davies

|

|

Dr. Kevin Davies is the editor in chief of Cell

Press and the author of

Cracking the Genome: Inside the Race to Unlock

Human DNA

(Free Press, 2001). A graduate of Oxford University,

he holds a doctorate in genetics from the University

of London.

|

Selected sources

Baharloo S., Service S.K., Risch N., Gitschier J., Freimer

N.B. "Familial aggregation of absolute pitch."

American Journal of Human Genetics, September 67,

755-8 (2000).

Grady, D. "Son Conceived To Provide Blood Cells For

Daughter." New York Times, October 4, 2000.

The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium.

"Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome."

Nature 409, 860-921 (2001).

Lichtenstein P., Holm N.V., Verkasalo P.K., Iliadou A.,

Kaprio J., Koskenvuo M., Pukkala E., Skytthe A., Hemminki

K. "Environmental and heritable factors in the causation

of cancer -- analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden,

Denmark, and Finland."

New England Journal Medicine, July 13, 343, 78-85

(2000).

Venter J.C. "A dramatic map that will change the world."

Daily Telegraph February 14, 2001.

Venter J.C. et al. "The sequence of the human genome."

Science 291, 1304-1351 (2001).

Photos: (1-6) WGBH/NOVA; (7) Kathy Blanchard.

Watch the Program Here

|

Our Genetic Future (A Survey)

Manipulating Genes: How Much is Too Much?

|

Understanding Heredity

Explore a Stretch of Code

|

Nature vs Nurture Revisited

Sequence for Yourself

|

Journey into DNA |

Meet the Decoders

Resources

|

Update to Program

|

Teacher's Guide

|

Transcript

Site Map

|

Cracking the Code of Life Home

Editor's Picks

|

Previous Sites

|

Join Us/E-mail

|

TV/Web Schedule

|

About NOVA

Watch NOVAs online

|

Teachers |

Site Map

|

Shop

|

Search |

To Print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

©

| Updated April 2001

|

|

|